Mortality and pathophysiology of acute kidney injury according to time of occurrence in acute heart failure

Matthias Diebold and Nikola Kozhuharov contributed equally and should be considered first authors.

Abstract

Aims

Acute kidney injury (AKI) during acute heart failure (AHF) is common and associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The underlying pathophysiological mechanism appears to have prognostic relevance; however, the differentiation of true, structural AKI from hemodynamic pseudo-AKI remains a clinical challenge.

Methods and results

The Basics in Acute Shortness of Breath Evaluation Study (NCT01831115) prospectively enrolled adult patients presenting with AHF to the emergency department. Mortality of patients was prospectively assessed. Haemoconcentration, transglomerular pressure gradient (n = 231) and tubular injury patterns (n = 253) were evaluated to investigate pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AKI timing (existing at presentation vs. developing during in-hospital period). Of 1643 AHF patients, 755 patients (46%) experienced an episode of AKI; 310 patients (19%; 41% of AKI patients) presented with community-acquired AKI (CA-AKI), 445 patients (27%; 59% of AKI patients) developed in-hospital AKI. CA-AKI but not in-hospital AKI was associated with higher mortality compared with no-AKI (adjusted hazard ratio 1.32 [95%-CI 1.01–1.74]; P = 0.04). Independent of AKI timing, haemoconcentration was associated with a lower two-year mortality. Transglomerular pressure gradient at presentation was significantly lower in CA-AKI compared to in-hospital AKI and no-AKI (P < 0.01). Urinary NGAL ratio concentrations were significantly higher in CA-AKI compared to in-hospital AKI (P < 0.01) or no-AKI (P < 0.01).

Conclusions

CA-AKI but not in-hospital AKI is associated with increased long-term mortality and marked by decreased transglomerular pressure gradient and tubular injury, probably reflecting prolonged tubular ischemia due to reno-venous congestion. Adequate decongestion, as assessed by haemoconcentration, is associated with lower long-term mortality independent of AKI timing.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) during acute heart failure (AHF) is common and associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and accelerated progression to chronic kidney disease.1, 2 However, current data suggest that the prognostic significance of AKI in AHF is not dictated by the serum creatinine increase per se but rather by the underlying pathophysiological mechanism. While serum creatinine increases due to adequate decongestion tend to occur later and may not portend a poor prognosis, the differentiation of true, structural AKI from hemodynamic pseudo-AKI remains a clinical challenge.

Aims

We aimed to assess the impact of AKI timing on mortality in a large, prospectively enrolled, well-characterized cohort of AHF patients. To assess potentially differing pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AKI timing, we assessed transglomerular pressure gradient, tubular injury patterns and haemoconcentration as well as their changes during AHF therapy.

Methods

Basics in Acute Shortness of Breath Evaluation Study (NCT01831115) prospectively enrolled adult patients presenting with dyspnoea as the chief complaint to the emergency department (ED). Only patients with a final adjudicated diagnosis of AHF were included in this analysis. This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. AKI was defined and graded according to serum creatinine criteria of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines as an increase in serum creatinine by at least 26.5 μmol/L within 48 h or an increase ≥1.5 baseline within the prior 7 days.3 AKI severity was graded in stage I (1.5–1.9 times baseline odds ratio ≥ 26.5 μmol/L) stage II (2.0–2.9 times baseline), and stage III (3.0 times baseline or increase ≥353.6 μmol/L or initiation of renal replacement therapy). Baseline steady-state kidney function was determined using electronic medical records for the last 6 months prior to the index hospitalization. In the absence of pre-admission data, the creatinine nadir during the index hospitalization was accepted as the presumptive baseline. Serum creatinine values during follow-up were available for 483 patients. Central venous pressure (CVP) was measured non-invasively by forearm compression sonography by a vascular specialist during working hours within the first 30 min after presentation to the ED in a subgroup of patients (n = 231). This method has been described and clinically validated against invasively measured CVP previously.4 The pressure when the vein completely collapsed corresponded to the intravasal venous pressure and was measured continuously. The difference between the level of the sonographic measurement point and the right atrial level was subtracted from the crude value for correction of the blood column height. Transglomerular pressure gradient was defined as the difference between systolic blood pressure and CVP.4

Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) isotype concentrations were determined in a cohort of 253 consecutive patients at presentation, Days 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and discharge (Diagnostics Development, Uppsala, Sweden). As previously published,5 we assessed the ratio between renal monomeric NGAL and neutrophilic dimeric NGAL to improve the detection of renal tubular injury.

Haemoconcentration was defined as any increase in at least three of the four haemoconcentration defining parameters [haemoglobin (Hb), haematocrit (Hct), albumin, and total protein] above admission values occurring simultaneously at any time during the hospitalization.6

To assess mortality, patients were contacted by telephone after 3, 6 and 12 months and annually thereafter. Referring physicians and administrative databases were contacted in case of uncertainties.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). An alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Discrete variables are expressed as counts (percentages) and continuous variables as median (25th and 75th percentile). Comparison between groups was performed by Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test if applicable for categorical variables and Kruskal–Wallis or Wilcoxon paired test for continuous variables. Bonferroni correction was used for pairwise comparisons if Kruskal–Wallis achieved a P value < 0.05. Cox regression survival curve analysis was adjusted for known mortality risk factors described in the ADHERE registry, the BIOSTAT-CHF study and the MEESI AHF risk score7-9 [age, blood urea nitrogen, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), high-sensitivity troponin T, potassium, haemoglobin, mean arterial pressure, New York Heart Association class IV and delta creatinine between steady state and peak and beta blocker use at baseline] and c-reactive protein, as a potential pathophysiological confounder.10 The proportional hazard assumption was tested by introducing an interaction with time and the variables of interest.

Results

Overall, 1643 AHF patients were included in this analysis; 18 patients were discharged directly from the ED and 300 patients required ICU treatment during the hospitalization. Overall, 755 patients (46%) experienced an episode of AKI. Of these, 310 patients (41%) presented to the ED with community-acquired AKI (CA-AKI), whereas 445 patients (59%) developed AKI during the in-hospital period. The median time until the occurrence of in-hospital AKI was 3 days (interquartile range [IQR 2–6]). The incidence of CA-AKI was similar in patients discharged directly from the ED and those requiring hospitalization (P = 0.76). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Of note, patients presenting with CA-AKI had lower levels of haemoconcentration defining parameters, significantly higher NT-proBNP and troponin T concentrations and more frequently required outpatient diuretic therapy before presentation. CA-AKI patients experienced higher degrees of AKI severity compared with in-hospital AKI patients (advanced AKI II/III: 43.5% vs. 20.7%; P < 0.01) corresponding to a higher delta creatinine between steady state and peak (72 μmol/L [IQR 46–127] vs. 57 μmol/L [IQR 41.89]; P < 0.01). Consequently, the need for ICU treatment was higher in CA-AKI patients compared with patients developing in-hospital AKI (28% vs. 20%, P = 0.01).

| Baseline characteristics | No AKI (n = 888) | CA-AKI (n = 310) | In-hospital AKI (n = 445) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 78 [69–85] | 78 [69–84] | 79 [73–84] | 0.03 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 531 (59.8) | 171 (55.2) | 251 (56.4) | 0.74 |

| Medical history, n(%) | ||||

| Hypertensive heart disease | 253 (35) | 94 (41.6) | 147 (41.8) | 0.97 |

| Myocardial infarction | 224 (29.9) | 68 (29.7) | 128 (35.2) | 0.17 |

| Diabetes | 246 (28.1) | 111 (36.3) | 141 (32.3) | 0.26 |

| COPD | 197 (22.6) | 84 (27.5) | 117 (26.8) | 0.85 |

| Stroke | 124 (14.7) | 59 (19.7) | 82 (20.0) | 0.93 |

| Treatment on admission, n (%) | ||||

| ACEI or ARB | 539 (62.2) | 199 (66.3) | 295 (67.5) | 0.74 |

| Beta-blocker | 499 (57.5) | 195 (64.4) | 281 (64.2) | 0.96 |

| Diuretic | 573 (65.9) | 243 (80.5) | 322 (73.2) | 0.02 |

| Clinical signs on admission, n (%) | ||||

| Jugular venous distension | 355 (43.6) | 106 (36.4) | 206 (51.0) | <0.01 |

| Oedema | 533 (61.8) | 182 (59.7) | 284 (65.6) | 0.10 |

| Rales | 538 (64) | 178 (59.7) | 268 (64.3) | 0.22 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 100 [88–114] | 91 [79–104] | 99 [86–111] | <0.01 |

| NYHA | 0.87 | |||

| Class I | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.91 |

| Class II | 64 (8) | 20 (7) | 21 (5) | 0.40 |

| Class III | 424 (51) | 139 (47) | 191 (48) | 0.89 |

| Class IV | 346 (41) | 135 (46) | 187 (47)) | 0.81 |

| Laboratory assessments on admission | ||||

| Protein (g/L) | 69 [66–73] | 70 [66–74] | 71 [67–75] | 0.03 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 130 [116–143] | 122 [107–137] | 123 [110–137] | 0.13 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 38 [35–42] | 36 [32–41] | 37 [33–41] | 0.12 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35 [32–38] | 34 [31–37] | 35 [32–38] | <0.01 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 93 [77–119] | 156 [118–219] | 115 [84–153] | <0.01 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 8.2 [5.9–11.5] | 15.1 [10.5–21.7] | 9.9 [7.2–14.8] | <0.01 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 4623 [2189–8680] | 8354 [3640–17539] | 6254 [3438–11 891] | 0.02 |

| WBC (G/L) | 8.6 [7.0–10.6] | 9.3 [7.0–12.8] | 8.6 [7.1–11.8] | 0.40 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 11 [5–27] | 17 [5–57] | 12 [5–32] | <0.01 |

| Hs-cTnT (ng/L) | 33 [19–57] | 49 [31–94] | 43 [24–81] | 0.05 |

| Creatinine steady state (μmol/L) | 85 [71–108] | 91 [68–119] | 103 [77–138] | <0.01 |

| eGFR steady state (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 66 (49–84) | 54 (36–81) | 50 (36–75) | 0.30 |

| Delta creatinine (μmol/L) | 19 [12–26] | 72 [46–127] | 57 [41–89] | <0.01 |

| Delta NT-proBNP (ng/L) | −1854 [−4363 to −338] | −3002 [−7952 to −267] | −1777 [−4623–0] | 0.01 |

| Delta weight (kg) | −2 [−5 - 0] | −2 [−5 - 0] | −2[−5–0] | 0.13 |

- Values are median [interquartile range] and numbers (percentages). P values are calculated between community-acquired AKI and in-hospital AKI using a Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test, or chi-square test for categorical variables. Delta creatinine is the difference of peak creatinine and baseline steady state creatinine; delta NT-proBNP is the difference between NT-proBNP at admission and discharge; delta weight is the difference between weight on admission and discharge. To convert creatinine values from μmol/L to mg/dL, divide by 88.4.

- ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AKI, acute kidney injury; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C-reactive protein; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; hsc-TnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; WBC, white blood cell count.

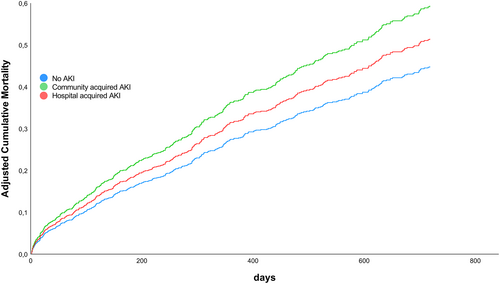

Impact of acute kidney injury timing on mortality

Acute kidney injury was associated with an increased 720-day mortality compared with no-AKI patients [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 1.21 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.99–1.48]; P = 0.07]. Importantly, when assessing the impact of AKI timing on mortality only CA-AKI but not in-hospital AKI was associated with an increased mortality compared to no-AKI (CA-AKI adjusted HR 1.32 [95%-CI 1.01–1.74]; P = 0.04; in-hospital AKI adjusted HR 1.15 [95%-CI 0.91–1.44]; P = 0.24) (Figure 1).

Transglomerular pressure gradient and tubular injury according to acute kidney injury timing

Age, gender, history of chronic kidney disease, creatinine at presentation, and AKI incidence were similar to the overall cohort in the subgroups with available CVP and urinary NGAL measurements.

Transglomerular pressure gradient at presentation was significantly lower in CA-AKI (102 mmHg [IQR 97–121]) compared with in-hospital AKI (126 mmHg [IQR 107–143]; P < 0.01) and no-AKI (125 mmHg [IQR 109–146]; P < 0.01). This was mainly driven by significantly lower systolic blood pressure levels in CA-AKI compared with in-hospital and no-AKI patients (CA AKI 125 mmHg [107–143], in-hospital AKI 140 mmHg [121–158]; P < 0.01, no AKI 138 mmHg [122–158]; P < 0.01). At discharge, glomerular pressure gradient was similar in patients with CA-AKI, (111 mmHg [IQR 102–120]), in-hospital AKI (118 mmHg [IQR 102–130]), and no AKI (117 mmHg [IQR 104–139]; P = 0.23). This was driven by a larger reduction in CVP (delta CVP: CA-AKI −5 mmHg [IQR −2 to −9]; in-hospital AKI: −1 mmHg [IQR 0 to −7]; no-AKI: −1 mmHg [IQR 0 to −5], P = 0.16) and stable systolic blood pressure levels in the CA-AKI group (delta systolic blood pressure: 1 mmHg [IQR 14 to −19]), compared with decreasing systolic blood pressure levels in the in-hospital (delta systolic blood pressure: −15 mmHg [IQR 2 to −31], P < 0.01) and no AKI (delta systolic blood pressure: −12 mmHg [3 to −29], P < 0.01) groups.

At presentation, urinary NGAL isotype ratio was significantly higher in patients presenting with CA-AKI compared with in-hospital AKI or no-AKI (CA-AKI 8.4 [IQR 6.6–13.0], in-hospital AKI 5.9 [IQR 3.5–10.3]; P < 0.01, no-AKI 5.7 [IQR 3.8–9.6]; P < 0.01). Urinary NGAL isotype ratio at presentation in CA-AKI was significantly higher than NGAL ratios at the time of in-hospital AKI (P = 0.02). Importantly, urinary NGAL isotype ratio in CA-AKI normalized during AHF treatment towards ratios observed in no-AKI and in-hospital AKI patients (Pfor groups = 0.76). Urinary NGAL isotype ratio remained unchanged between presentation, the time of AKI and discharge in in-hospital AKI patients (baseline 5.9 [IQR 3.5–10.3]; time of AKI 5.7 [IQR 3.8–13.1]; P = 0.61; discharge 5.4 [IQR 4.0–9.5]; P = 0.58). Similarly, urinary NGAL isotype ratio remained stable between admission and discharge in no-AKI patients (admission 5.7 [IQR 3.8–9.6]; discharge 6.3 [IQR 4.3–9.6]; P = 0.55).

Renal function at discharge and during long-term follow-up according to acute kidney injury timing

During the course of the hospitalization, renal function significantly improved in both AKI patient groups (CA-AKI: peak creatinine 170 μmol/L [IQR 130–249], creatinine at discharge 116 μmol/L [IQR 89–173], P < 0.01, in-hospital AKI: peak creatinine 171 μmol/L [IQR 128–232], creatinine at discharge 134 μmol/L [IQR 103–186], P < 0.01). Importantly, the remaining degree of acute renal dysfunction (i.e. delta discharge creatinine to steady state creatinine) was smaller in CA-AKI (21 μmol/L [IQR 0–56]) compared with in-hospital AKI patients (29 μmol/L [IQR 12–53], P < 0.01). The median renal follow-up was 458 days [IQR 328–580]. Renal function after long-term follow up was similar in both AKI groups (CA-AKI estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]: 47 mL/min [IQR 29–67] vs. in-hospital AKI 43 mL/min [IQR 29–60], P = 0.99) but inferior to no-AKI patients (no-AKI eGFR: 57 mL/min [IQR 38–74], P < 0.01). This mirrored the distribution at baseline (Table 1). Changes in eGFR from steady state renal function to follow-up eGFR were similar in all three groups (P = 0.37).

As a surrogate parameter of adequate decongestion, haemoconcentration was achieved in 445 patients (27%) during AHF treatment and was equally common in CA-AKI (n = 78, 27%) and in-hospital AKI (n = 119, 31%). Similarly, hemodynamic stress (change in NT-proBNP) and cardiomyocyte injury (change in troponin T) decreased more significantly in CA-AKI compared with in-hospital AKI patients (both P = 0.01). At the time of discharge, NT-proBNP (P = 0.27) and troponin T (P = 0.58) concentrations were similar in CA-AKI and in-hospital AKI patients. No differences existed in the frequency of ACEI/ARB (P = 0.76) and beta-blocker (P = 0.09) therapy at discharge between CA-AKI and in-hospital AKI patients, while the need for long-term diuretic therapy was lower in CA-AKI compared with in-hospital AKI patients (P = 0.02). Haemoconcentration was associated with an improvement in 2-year mortality of AKI patients independent of the timing of AKI towards the mortality of no-AKI patients (Ca-AKI: adjusted HR 1.16 [95%-CI 0.86–1.56]; P = 0.32 and in-hospital AKI: adjusted HR 1.06 [95%-CI 0.83–1.36]; P = 0.63).

Conclusions

We report seven major findings: First, 41% of all AKI episodes in AHF exist already at presentation to the ED. Second, only CA-AKI, but not in-hospital AKI, appears to be independently associated with increased long-term mortality compared to no-AKI. Hence, assessing only in-hospital serum creatinine changes fails to identify this vulnerable patient subgroup. Third, parameters of volume overload appear to be higher in CA-AKI patients leading to a significantly lower transglomerular pressure gradient in CA-AKI compared with in-hospital AKI episodes. Fourth, CA-AKI is marked by significant tubular injury, probably reflecting prolonged tubular ischemia due to reno-venous congestion and/or forward cardiac failure. Fifth, contrastingly tubular injury does not occur during in-hospital AKI, suggesting a hemodynamic increase in serum creatinine rather than structural renoparenchymal damage. Sixth, tubular injury in CA-AKI is transient and decreases during AHF therapy, possibly reflecting the attenuation of renal injury.11 Seventh, independent of the timing of AKI, adequate decongestion as assessed by haemoconcentration is associated with lower long-term mortality. Hence, adequate decongestion remains the cornerstone of AHF treatment even in patients presenting with CA-AKI, in whom treatment is often initiated cautiously by treating clinicians. Additionally, every effort should be made to raise awareness about the detrimental effects of delayed ED presentations. Life-saving heart failure therapies by ACEI/ARB and beta-blockers should not be routinely discontinued in CA-AKI patients.

Limitations

Due to the observational nature of our study, we cannot fully exclude that residual differences in heart failure severity between CA-AKI and in-hospital AKI patients might have contributed to differences in long-term mortality. However, we statistically adjusted for a range of powerful mortality risk factors and pathophysiological confounders. Additionally, we found factors associated with long-term prognosis at discharge [i.e. heart failure therapy, hemodynamic stress (NT-proBNP) and decongestion (haemoconcentration)] to be similar in both AKI groups, which appears to support our conclusions. Furthermore, the degree of persistent acute renal dysfunction and the need for chronic diuretic therapy at discharge were significantly lower in patients initially presenting with CA-AKI.12

Conflict of interest

Dr Breidthardt received research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PASMP3-134362), University Hospital Basel, Abbott and Roche as well as speakers honoraria from Roche. Professor Mueller received research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Heart Foundation, the European Union, the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, the University of Basel, 8sense, Abbott, ALERE, Astra Zeneca, Beckman Coulter, Biomerieux, BRAHMS, Critical Diagnostics, Nanosphere, Roche, Siemens, Singulex, and the University Hospital Basel, as well as speaker or consulting honoraria from Abbott, ALERE, Astra Zeneca, BG Medicine, Biomerieux, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, BRAHMS, Cardiorentis, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Singulex, and Siemens. Dr Venge owns shares in Diagnostics Development (Uppsala, Sweden) and owns worldwide granted patents of measuring NGAL in human diseases. The other authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the University of Basel, the University Hospital Basel, the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, BRAHMS, Roche, and Singulex.