Intractable coronary fibromuscular dysplasia leading to end-stage heart failure and fatal heart transplantation

Abstract

Coronary fibromuscular dysplasia is uncommon, and even rarer its unstable and recurrent course. We present the unique case of a 52-year-old woman who underwent in total 12 coronary angiographies and three percutaneous coronary intervention within 24 months because of repetitive acute coronary syndromes due to refractory spasm, dissection, restenosis all leading to end-stage heart failure, and heart transplantation. The patient died 12 days after the heart transplantation complicated by intraoperative acute thrombotic occlusion of left anterior descending artery of the graft despite normal pretransplant coronary angiography. Autopsy of the recipient heart confirmed coronary fibromuscular dysplasia with massive intimal hyperplasia and restenosis.

1 Introduction

Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) is a nonatherosclerotic, noninflammatory artery disease, mainly affecting middle-aged women (female to male ratio 9:1). FMD may affect any artery, but most commonly (about 65% of cases), it is found in the carotid or renal artery.1-3 Coronary FMD is infrequent (about 0.6–5%), and its manifestations are nonspecific including dissection, spasm, tubular narrowing, or tortuosity.4-6 No evidence-based management on diagnosis and treatment currently exists, so a case-by-case approach discussed within a multidisciplinary heart team is desirable. Conservative treatment is pursued in most acute coronary FMD events. In unstable patients with ongoing myocardial ischaemia or severe recurrent symptoms and who may require an interventional approach, therapeutic options remain unsatisfactory.

2 Case report

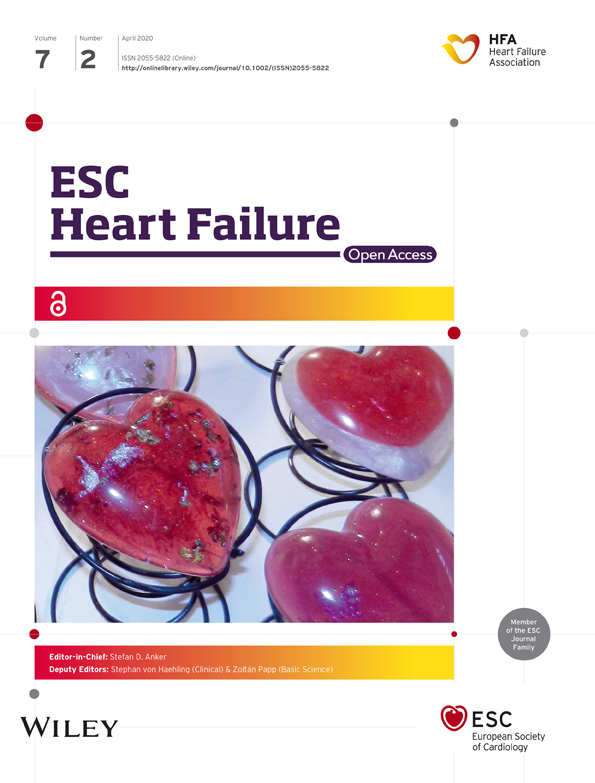

A 52-year-old, non-smoking woman with hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and recurrent migraine presented to the emergency department with acute chest pain associated with electrocardiogram showing ST-segment depression in leads V3–V6 (Figure 1A), evolving early into widespread ST-segment changes pathognomonic for critical lesion of the left main (LM) coronary artery (Figure 1B), and associated with elevated blood troponin I and creatine kinase (60.98 μg/L and 2247 U/L, respectively). Transmural myocardial infarction was confirmed at coronary angiography with 90% stenosis of the LM and diffuse spasm of the left coronary artery. Intracoronary nitrates resolved the spasm; however, the stenosis of the ostial and mid-LM persisted (Figure 1C). Given emergent conditions, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and 10 mm biolimus-eluting stenting of the LM culprit lesion were performed.7, 8 Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) confirmed correct stent position and TIMI-3 flow was observed. The patient received secondary prevention therapy for ischaemic coronary artery disease (CAD) at discharge, including aspirin, ticagrelor, metoprolol, perindopril, and rosuvastatin.

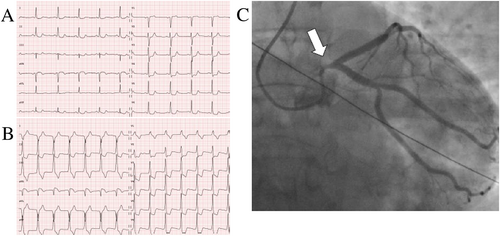

One month later, the patient experienced ischaemic stroke due to dissection of the internal carotid artery (Figure 2A). In view of these two acute vascular events, according to guidelines,1-3 we evaluated other arterial beds and found multifocal bilateral stenosis of renal arteries (Figure 2B).

Four months later (Table 1), the patient started to present recurrent acute non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions (NSTEMIs). She underwent serial coronary angiographies including optical coherence tomography (OCT), which showed mild restenosis but no dissection in the previously stented LM, while angiography revealed severe coronary artery spasm (CAS) of the ostial-proximal left anterior descending (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCX), which almost completely disappeared at both sides after intracoronary nitrates. Conservative treatment including non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker, nitrates, nicorandil, and ranolazine at maximal tolerated doses was gradually implemented.4

| Time (months) | Event |

|---|---|

| 0 | LM occlusion |

| 4–6 | Recurrent CAS |

| 6 | OHCA |

| 6–12 | Recurrent CAS |

| 12 | In-stent restenosis of LAD and LCX |

| 12 | Suspected dissection of LM |

| 20 | Thrombotic complete occlusion of LAD |

| 24 | HTX and acute occlusion of LAD of the graft |

- CAS, coronary artery spasm; FMD, fibromuscular dysplasia; HTX, orthotopic heart transplantation; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LM, left main coronary artery; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

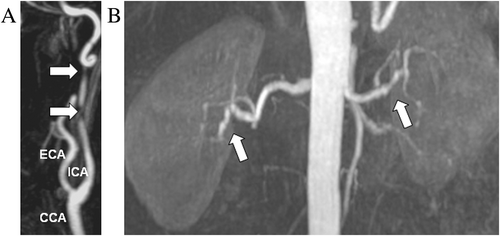

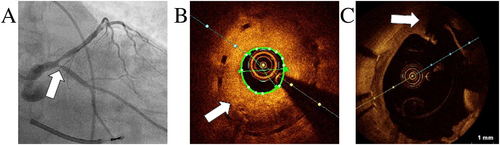

Nevertheless, three months later, the patient suffered a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Immediately after successful resuscitation, coronary angiography was performed, showing 90–99% stenosis of the bifurcation of LAD and LCX (Medina classification 0,1,1) (Figure 3A). OCT ruled out dissection or significant atherosclerosis but showed widespread intima thickening. Intracoronary nitrates rapidly reduced the angiographic obstruction (final TIMI-3 flow), suggesting severe spasm as the cause of OHCA on top of tubular restenosis (Figure 3B). However, conservative strategy for spasm early proved ineffective, as the patient presented with ongoing diffuse transmural myocardial ischaemia and haemodynamic instability. The case was discussed within our multidisciplinary heart team, and an interventional approach by PCI and double off-label everolimus-eluting bioresorbable scaffold (BRS) were performed. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was also implanted for secondary prevention.9

Next months were characterized by recurrent NSTEMIs, which were assumed a result of drug-resistant CAS. Following several reports of cervical sympathectomy being potentially beneficial in such cases, this thoracoscopic procedure was offered to the patient, but she refused.10

Six months after the OHCA, in-stent restenosis due to excessive neointimal hyperplasia of the previously stented bifurcation occurred (Figures 4A and 4B). Moreover, OCT revealed LM dissection beneath the first implanted stent associated with strut rupture (Figure 4C). This dissection might be retrospectively suspected to be a cause of the primary event, although its location, beneath a ruptured stent, makes this hypothesis difficult to verify.

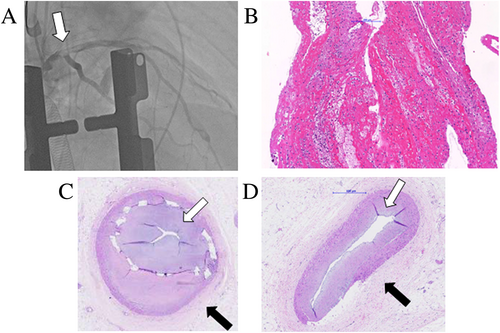

Finally, 20 months after the initial event, the patient experienced anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction due to acute complete occlusion of proximal LAD, which may have been fostered by the previously implanted BRS. This event led to a severe reduction of left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 20%, and rapidly deteriorating end-stage heart failure. The decision was to put the patient on a super-urgent waiting list for orthotopic heart transplantation (HTX). A 50-year-old donor heart was checked by angiography before explant with no evidence of CAD. Nevertheless, immediately after implant of the donor heart, surgeons observed no flow in the LAD of the graft (Figure 5A). Regardless of emergency double venous bypass graft, a cardiogenic shock occurred, complicated later by multi-organ failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Histopathology of specimen extracted by angiography from the graft LAD showed a fresh white artery thrombus as the cause of the vessel occlusion (Figure 5B). The patient died after 12 days on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Post-mortem autopsy samples of coronary arteries from the recipient heart showed a typical pattern of coronary intimal-type FMD: excessive intimal hyperplasia with ‘star-shaped’ lumen and concentric adventitial fibrosis (Figure 5C), without any alterations typical of atherosclerosis or vasculitis.1, 2, 11 Moreover, massive occlusive in-stent restenosis was visualized, which is notably associated with both FMD and BRS (Figure 5D).

3 Discussion

The case describes a highly unstable, treatment-resistant (conservative and interventional) combination of coronary complications resulting in refractory CAS, dissection, stent-related complications progressively leading to end-stage heart failure. This recurrent presentation is probably due to a combination of various factors: local characteristics of a lesion, systemic factors, iatrogenic impact of PCI, and BRS, possibly aggravated by predisposing local factors as restenosis highlighted in the histopathological image with severe intimal hyperplasia (Figure 5C).

The patient underwent PCI with stent for the first severe LM obstruction. According to the European guidelines for management of unprotected LM disease available at that moment,7 coronary artery bypass grafting was recommended regardless of anatomic complexity for revascularization for stable CAD. However, PCI could be considered for selected LM lesions depending on lesion location, vessel involvement, and SYNTAX score, especially for ostial or mid-lesion and low SYNTAX score, as in our case. In emergent condition and acute myocardial infarction, LM PCI appeared to have remarkably high (89%) in-hospital survival.8 Use of IVUS is recommended in decision-making process. In our case, no initial dissection was detectable by IVUS. The remote possibility that the patient could have presented dissection as an initial event cannot completely be excluded because OCT was not performed given the acute presentation.

The patient presented the OHCA, which was caused by severe CAS. Stent placement is a therapeutic alternative in patients with spasm refractory to maximal aggressive medical therapy.12 Patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest and presenting with CAS have a poorer prognosis and show a high prevalence of ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmias.9 Therefore, our patient also underwent an ICD implantation for secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

Retrospectively, we have to admit that the use of BRS was definitely a wrong decision and led to catastrophic accelerated clinical course in the patient with FMD. Concerns about restoration of vessel functionality and thrombogenicity were not available at the time these stents were delivered.13 Next recurrent NSTEMIs could be associated with both drug-resistant CAS, which is frequently reported with coronary FMD,4, 5 and CAS triggered by BRS.14 We may hypothesize that the final acute complete occlusion of LAD was due to late acute thrombotic occlusion probably due to the presence of previously implanted BRS. Retrospectively, another alternative hypothesis of this acute occlusion should be taken into account: progressive massive intimal hyperplasia due to FMD and aggravated by BRS (Figure 5C), over time, led to sub-occlusion of the vessel with recurrent nitrates-resistant CAS. The final complete catastrophic occlusion of LAD may have also been caused by severe CAS over the sub-occluded vessel.

The patient underwent HTX, which was complicated by intraoperative acute akinesia of the new heart due to thrombotic occlusion of the graft LAD. Early coronary complications of HTX are very rare and mainly associated with procedural manipulation or directly related to donor heart, especially with CAD,15, 16 as transmitted atherosclerosis results in a two-fold to three-fold increased risk for early graft failure.17 Most eurotransplat regions recommend to screen every donor over 40 years old by angiography or when it is requested by surgeon (also in our case), when some risk factors are suspected. The question if donor heart angiography increases endothelium trauma is difficult to answer. We could not find any literature specific for heart donors. However, a similar question was posed for kidney donors.18 The authors conclude that the administration of contrast medium had no influence on renal function at 3 or 6 months after transplantation, so in conclusion, fears that donor kidneys might be harmed by contrast medium appeared to be unfounded. The young donor heart in our case presented no evidence of CAD at pretransplant angiography. In vivo thrombus extraction during angiography before patient death revealed a white artery thrombus of the LAD, indicating a recent coronary thrombotic event (Figure 5B). Peri-procedural related inflammation and thrombogenicity increase a risk of myocardial ischaemia.15 Although painful attention was paid to avoid mechanical damage during the transplantation procedures, the probable cause of the unexpected fatal finding could be related to inadvertent embolism due to manipulation during the complex HTX procedure or, less probably, secondary to hyperacute vascular rejection (although preoperatively direct lymphocyte crossmatch test was negative),19, 20 or to a putative presence of systemic vascular disease.21-23

Histopathological examination of recipient heart confirmed intimal-type FMD (Figure 5D). According to the European and US consensus,1, 2 intimal-type FMD is associated with focal angiographic pattern mainly localized at ostial or proximal part of a vessel, in contrast to medial type, which is rather associated with multifocal pattern located at mid or distal vessel. However, two types can coexist in one subject, as shown in our case by a presence of multifocal bilateral renal artery stenosis and intimal histopathological type of coronary arteries. In general, coronary FMD has a good prognosis (low mortality 0.8% during a median follow-up period of 23.9 months), and conservative medical treatment for acute events, as dissection or spasm, is recommended, as most of lesions heal spontaneously. Aggressive measures as PCI, coronary artery bypass grafting, or even HTX, as only means of establishing coronary flow, can be considered only in life-threading or with ongoing ischaemia cases.6

Starting from the first event and during the whole 2-year course, the patient was closely monitored by our heart team and differential diagnosis was performed as follows. Review of laboratory testing showed normal inflammation parameters (especially no C-reactive protein or eosinophils), normal coagulation factors, catecholamine level, and autoimmune panel. Medical history and clinical findings reasonably exclude in a well compliant patient other possible triggers such as over-the-counter antimigraine medications, as well as alcohol and abuse of recreational drugs (marijuana and amphetamine).24 The patient's history reveals involvement of peripheral vessels (carotid dissection and bilateral multifocal renal artery stenosis), and family history was positive for the patient's brother having dissection of the vertebral artery at the age of 27. All these findings, together with histopathological findings, were consistent with the diagnosis of multivessel FMD and reasonably ruled out alternative diagnoses such as aortic dissection, pseudoxantoma elasticum, vasculities, Marfan syndrome, Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, segmental arterial mediolysis, or Loeys-Dietz syndrome.25-27

In conclusion, coronary FMD has generally a favourable prognosis, and conservative treatment is preferred. This case of unstable coronary FMD rapidly leading to end-stage heart failure and treatment-resistant fatal evolution illustrates elusiveness of diagnosis and dilemma, challenges, and potential harm of invasive treatment of coronary FMD. The optimal management of patient with FMD and end-stage heart failure unfortunately is unknown given a rarity of the condition, and there is a growing need for more studies in these patients based on international large population registries. The acute fatal thrombotic coronary complication during HTX remains so far unexplained.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.