Liraglutide and weight loss among patients with advanced heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction: insights from the FIGHT trial

Abstract

Aims

Obesity is present in up to 45% of patients with heart failure (HF). Liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor antagonist, facilitates weight loss in obese patients. The efficacy of liraglutide as a weight loss agent among patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and a recent acute HF hospitalization remains unknown.

Methods and results

The Functional Impact of GLP-1 for Heart Failure Treatment study randomized 300 patients with HFrEF (ejection fraction ≤ 40%), both with and without diabetes and a recent HF hospitalization to liraglutide or placebo. The primary outcome for this post hoc analysis was the change in weight from baseline to last study visit. We conducted an ‘on-treatment’ analysis of patients with at least one follow-up visit on study drug (123 on liraglutide and 124 on placebo). The median age was 61 years, 21% were female, and 69% of patients had New York Heart Association functional Class III or IV symptoms. The median ejection fraction was 25% (25th, 75th percentile 19–32%). Liraglutide use was associated with a significant weight reduction [liraglutide −1.00 lbs vs. placebo 2.00 lbs; treatment difference −4.10 lbs; 95% confidence interval (CI) −7.94, −0.25; P = 0.0367; percentage treatment difference −2.07%, 95% CI −3.86, −0.28; P = 0.0237]. Similar results were seen after multivariable adjustments. Liraglutide also significantly reduced triglyceride levels (liraglutide 7.5 mg/dL vs. placebo 12.0 mg/dL; treatment difference −33.1 mg/dL; 95% CI −60.7, −5.6; P = 0.019).

Conclusions

Liraglutide is an efficacious weight loss agent in patients with HFrEF. These findings will require further exploration in a well-powered cardiovascular outcomes trial.

Introduction

Obesity is common and present in up to 45% of patients with acute and chronic heart failure (HF).1, 2 Liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor antagonist, has been shown to facilitate weight loss in obese and overweight patients irrespective of diabetes status.3, 4 Liraglutide (at a dosage of 3.0 mg/day) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in chronic weight loss management among patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 and one or more obesity-related co-morbidities (i.e. hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidaemia).5 However, there are limited data addressing the efficacy of liraglutide as a weight loss agent among patients with HF. The liraglutide, a GLP-1 analogue, on left ventricular function in stable chronic HF patients with and without diabetes (LIVE) trial, demonstrated that liraglutide was associated with increased weight loss compared with placebo [ref]. In order to address this knowledge gap, we conducted an analysis of the Functional Impact of GLP-1 for Heart Failure Treatment (FIGHT) study6 to evaluate the hypothesis that liraglutide use was associated with a greater reduction in weight, independent of changes in fluid status, compared with placebo.

Methods

Study overview

The primary objective of the FIGHT study was to test the hypothesis that, compared with placebo, therapy with liraglutide after an acute HF hospitalization would be associated with greater clinical stability at 6 months. In contrast to the intention-to-treat analysis pre-specified for the FIGHT study, the present analysis focused on patients that had at least one study visit while on study drug (‘on-treatment’ population). The design and primary results of the FIGHT study were previously reported.6, 7 Briefly, the FIGHT study was a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of patients with HF and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (≤40% within the preceding 3 months). Patients were also required to have (i) a recent (within 14 days) HF hospitalization and (ii) a pre-admission oral diuretic dose of at least 40 mg of furosemide or an equivalent loop diuretic. All subjects provided written informed consent. Key exclusion criteria were (i) recent acute coronary syndrome or coronary intervention, (ii) intolerance of GLP-1 agonist therapy, and (iii) severe renal, hepatic, or pulmonary disease. The FIGHT study included patients with and without diabetes. Overall, 300 patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive liraglutide or placebo as a daily subcutaneous injection. Liraglutide was titrated up to 1.8 mg/day within the first 30 days of the trial. Study visits occurred at days 30, 90, and 180. Participants were called at a mean of 210 days to determine adverse event status. The primary endpoint was a global rank score in which all participants were ranked across three hierarchical tiers: time to death, time to rehospitalization for HF, and time-averaged proportional change in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level from baseline to 180 days. Compared with placebo, liraglutide had no significant effect on the primary endpoint.

Endpoint definition

The primary outcome of the present analysis was the change in body weight from baseline to last completed at least one study visit while on study drug (representing an on-treatment analysis). We pre-specified the following subgroups of interest: BMI above and below the median, diabetes, and patients with an FDA labelling indication for liraglutide as weight loss therapy (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2) and one or more obesity-related co-morbidity (i.e. hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidaemia). Interaction terms were used to assess for possible heterogeneity in treatment effect by subgroup. Secondary outcomes included the change in metabolic parameters including HbA1c and triglyceride levels. Adverse events of interest were compared between liraglutide and placebo and included anticipated disease-related, severe hypoglycaemic, or hyperglycaemic events. Anticipated disease-related events included arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, acute coronary syndromes, worsening HF, cerebrovascular events, venous thrombo-embolism, light-headedness, pre-syncope, syncope, or worsening renal function.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics between patients receiving liraglutide vs. placebo were compared using descriptive statistics. All categorical data were reported as frequencies and percentages and continuous data as median values (with interquartile range). Differences in weight, HbA1c, and triglycerides from baseline to last completed follow-up visit were assessed between liraglutide and placebo. To assess for weight changes independent of fluid status, the treatment differences were adjusted using (i) baseline NT-proBNP and baseline congestion score; (ii) baseline NT-proBNP, change in NT-proBNP from baseline to last completed visit, baseline congestion score, and change in baseline congestion score; and (iii) change from baseline to last completed visit NT-proBNP and change from baseline congestion score to last completed visit. Among patients receiving liraglutide and placebo, patients with completed data for modelling and with weight at baseline and follow-up weight were used in the analysis. The congestion score was composed of the following: orthopnoea (≥2 pillows = 2 points; <2 pillows = 0 points), and oedema (trace = 0 points; moderate = 1 point; severe = 2 points).8 SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

Funding and manuscript presentation

The FIGHT study was funded by the Heart Failure Network of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The FIGHT study was approved by the research network's protocol review committee and monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board. The ethics committee at each participating site approved the trial design. Database management and statistical analysis were performed by the Duke Clinical Research Institute. The authors take responsibility for the manuscript's integrity and had control and authority over its preparation and the decision to publish.

Results

Baseline characteristics

There were 247 patients with at least one study visit while on study drug: 123 were receiving liraglutide and 124 were receiving placebo (Table 1). The median age was 61 years, and 21% (n = 53) were female. The median BMI was 32.0 kg/m2, and 58% (n = 144) had diabetes. Sixty-six per cent (n = 162) of patients had a New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III while 4% (n = 9) had NYHA Class IV. The median EF was 25% (25th, 75th percentile 19–32%), and the median NT-proBNP was 1927 pg/mL (25th, 75th percentile 1037–4048 pg/mL). Baseline demographics were well balanced among patients assigned to placebo vs. liraglutide, except for HF aetiology [ischaemic cardiomyopathy; liraglutide 88% (n = 108) vs. placebo 75% (n = 93); P < 0.01] and history of chronic renal insufficiency [liraglutide 45% (n = 54) vs. placebo 31% (n = 39); P = 0.03]. Baseline weight was 206.1 lbs in patients receiving liraglutide and 212.6 lbs in patients receiving placebo. There was comparable adherence to the study drugs as the distribution of final day visits was balanced between the placebo and liraglutide groups (Supporting Information, Table S1). The antihyperglycaemic medication use among patients with diabetes was balanced between patients randomized to liraglutide vs. placebo (Supporting Information, Table S2).

|

Placebo (N = 124) |

Liraglutide (N = 123) |

Total (N = 247) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.5 (49.5, 66.0) | 61.0 (52.0, 68.0) | 61.0 (51.0, 67.0) |

| Gender (Female) | 23% (29) | 20% (24) | 21% (53) |

| Race (White) | 61% (76) | 54% (66) | 57% (142) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 9% (11) | 3% (4) | 6% (15) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.9 (25.4, 38.9) | 31.4 (27.1, 36.1) | 32.0 (26.3, 37.2) |

| NYHA Class | |||

| I | 2% (2) | 2% (2) | 2% (4) |

| II | 26% (31) | 30% (36) | 28% (67) |

| III | 70% (84) | 64% (78) | 66% (162) |

| IV | 3% (3) | 5% (6) | 4% (9) |

| KCCQ overall summary score | 40.6 (27.6, 61.3) | 43.8 (29.7, 62.5) | 42.7 (28.9, 61.9) |

| Six-min walk distance (m) | 212.9 (148.5, 311.8) | 231.7 (146.3, 312.0) | 222.6 (146.4, 312.0) |

| Weight (lbs) | 216.6 (168.8, 258.7) | 206.1 (178.0, 244.8) | 212.6 (173.5, 250.0)** |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 107.0 (98.0, 118.0) | 108.0 (99.0, 118.0) | 107.0 (98.0, 118.0) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 76.0 (68.5, 88.0) | 75.0 (68.0, 86.0) | 76.0 (68.0, 87.0) |

| Heart failure duration (years) | 6.2 (3.7, 10.9) | 6.7 (3.4, 12.6) | 6.6 (3.4, 12.0) |

| Ischaemic HF aetiology* % (n) | 75% (93) | 88% (108) | 81% (201) |

| Hypertension % (n) | 75% (93) | 80% (97) | 77% (190) |

| History of atrial fibrillation % (n) | 46% (57) | 47% (57) | 47% (114) |

| Diabetes % (n) | 60% (75) | 56% (69) | 58% (144) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency* % (n) | 31% (39) | 45% (54) | 38% (93) |

| Beta-blocker use % (n) | 94% (117) | 93% (114) | 94% (231) |

| ACE/ARB use % (n) | 73% (90) | 73% (89) | 73% (179) |

| Hydralazine use % (n) | 31% (39) | 31% (38) | 31% (77) |

| Long-acting nitrate use % (n) | 39% (48) | 35% (43) | 37% (91) |

| Aldosterone antagonist use % (n) | 63% (78) | 60% (73) | 62% (151) |

| Loop diuretic use % (n) | 100% (124) | 98% (121) | 99% (245) |

| Digoxin use % (n) | 38% (47) | 36% (44) | 37% (91) |

| Calcium channel blocker use % (n) | 2% (3) | 7% (9) | 5% (12) |

| Any lipid-lowering agent % (n) | 75% (93) | 68% (84) | 72% (177) |

| Antiplatelet use % (n) | 69% (85) | 71% (87) | 70% (172) |

| Anticoagulant use % (n) | 55% (68) | 50% (62) | 53% (130) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) % (n) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.8) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.8) |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.7 (6.0, 7.9) | 6.6 (5.9, 7.6) | 6.6 (5.9, 7.9) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 130.5 (108.0, 168.0) | 133.5 (111.0, 165.0) | 132.0 (109.0, 167.0) |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 35.0 (28.0, 46.0) | 35.5 (29.0, 49.0) | 35.0 (29.0, 47.0) |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 67.5 (57.0, 94.0) | 69.0 (56.0, 96.0) | 69.0 (57.0, 96.0) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 97.5 (75.0, 145.0) | 105.5 (74.0, 144.0) | 101.0 (74.0, 144.0) |

| Core lab NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 1891.00 (1016.00, 3927.00) | 1937.00 (1141.00, 4227.00) | 1927.50 (1037.00, 4048.00) |

| Core lab cystatin C (mg/L) | 1.42 (1.13, 1.81) | 1.31 (1.04, 1.72) | 1.35 (1.08, 1.75) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7 (3.4, 4.1) | 3.7 (3.4, 4.1) | 3.7 (3.4,4.1) |

| Echocardiogram ejection fraction (%) | 25.10 (19.00, 32.00) | 25.00 (19.00, 31.28) | 25.00 (19.00, 32.00) |

- ACE/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin-receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

- Data reported as median with 25th and 75th percentile unless otherwise stated.

- 3.7 +/− 0.6.

- * Significant difference between treatments (P < 0.05).

- ** P = 0.6155.

Liraglutide and weight loss

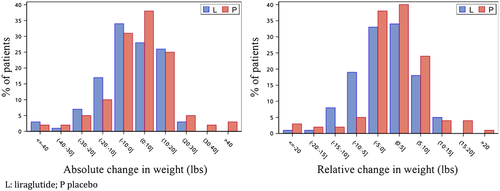

Among patients receiving liraglutide (with completed data for modelling and with weight at baseline and follow-up weight), the baseline weight was 208 lbs compared with 203.5 lbs at last study visit, while in patients receiving placebo, the baseline weight was 216.5 lbs compared with 217.0 lbs at last study visit (Table 2). There was an overall treatment difference between liraglutide and placebo of −4.10 lbs [95% confidence interval (CI) −7.94, −0.25; P = 0.0367; Table 2 and Figure 1]. The percentage difference in weight change between treatment arms was −2.07% (95% CI −3.86, −0.28; P = 0.0237). After adjustment with NT-proBNP and baseline congestion score, the weight loss treatment difference between liraglutide and placebo persisted (−4.19 lbs; 95% CI −8.05, −0.33; P = 0.033). After adjustment for baseline NT-proBNP, change in NT-proBNP from baseline to last completed visit, baseline congestion score, and change in baseline congestion score to last study visit, there was a numerical trend towards a weight loss treatment difference with liraglutide (−3.94 lbs; 95% CI −7.96, 0.08; P = 0.055). Similarly, after adjustment with change from baseline to last completed visit NT-proBNP and change from baseline congestion score, there was a numerical trend towards a weight loss treatment difference with liraglutide compared with placebo (−3.80 lbs; 95% CI −7.82, 0.23; P = 0.064).

|

Liraglutide (n = 119) |

Placebo (n = 123) |

Absolute treatment difference and 95% CI with P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline weight (lbs) | 208.0 (181.0, 244.8) | 216.5 (168.3, 259.3) | |

| Last visit weight (lbs) | 203.5 (177.1, 249.4) | 217.0 (175.0, 255.0) | |

| Weight change | −1.00 (−9.00, 10.00) | 2.00 (−5.51, 11.00) | −4.10 (−7.94, −0.25); P = 0.0367 |

- CI, confidence interval.

- Data presented as median with interquartile range unless otherwise specified.

Body mass index did not modify the relationship between liraglutide and weight loss (interaction P-value = 0.57; Supporting Information, Tables S3 and S4). Furthermore, the relationship between liraglutide and weight loss was not modified by the presence of diabetes (interaction P-value = 0.65) or the presence of an FDA label indication for liraglutide as weight loss agent (interaction P-value = 0.50).

Overall, 85 (69%) of patients in the liraglutide arm and 91 (73%) of patients in the placebo arm achieved target dosing before the last study visit used in our analysis (Supporting Information, Table S5). Overall, it appears that numerically, the greatest degree of weight loss occurs with the target dose of liraglutide (1.8 mg) (Supporting Information, Table S6).

Liraglutide and change in glycaemic control and triglycerides levels

Patients receiving liraglutide had HbA1c percentage of 6.50 at baseline and 5.90 at last study visit. In comparison, among patients receiving placebo, HbA1c percentage was 6.95 at baseline and 6.60 at last study visit (Table 3). There was a significant treatment difference in HbA1c levels between liraglutide and placebo (−0.48; 95% CI −0.92, −0.04; P = 0.033; Table 3). Furthermore, there was a significant reduction in triglyceride levels between patients receiving liraglutide vs. placebo (−33.1 mg/dL; 95% CI −60.7, −5.6; P = 0.019; Table 4).

|

Liraglutide (N = 63) |

Placebo (n = 70) |

Absolute treatment difference and 95% CI with P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 6.50 (5.80, 7.10) | 6.95 (6.00, 7.90) | |

| Last visit HbA1c (%) | 5.90 (5.70, 6.50) | 6.60 (5.80, 7.90) | |

| HbA1c change | −0.30 (−0.70, 0.10) | 0.00 (−0.70, 0.50) | −0.48 (−0.92, −0.04); P = 0.0328 |

- CI, confidence interval.

- Data presented as median with interquartile range unless otherwise specified.

|

Liraglutide (n = 74) |

Placebo (n = 71) |

Absolute treatment difference and 95% CI with P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline triglycerides (mg/dL); mean (25th, 75th) | 103.5 (75.0, 149.0) | 97.0 (78.0, 124.0) | |

| Last visit triglycerides (mg/dL); mean (25th, 75th) | 108.0 (76.0, 152.0) | 115.0 (80.0, 166.0) | |

| Triglycerides change; mean (25th, 75th) | 7.5 (−13.0, 40.0) | 12.0 (−12.0, 75.0) | −33.1 (−60.7, −5.6); P = 0.0186 |

- CI, confidence interval.

- Data presented as median with interquartile range unless otherwise specified.

Serious adverse events

Overall, among patients on treatment who had at least one study visit, 6% (n = 14) of patients had a severe hypoglycaemia event, 16% (n = 39) had a severe hyperglycaemic event, and 59% (n = 146) had an anticipated disease-related event. There was no difference between any serious adverse events among patients receiving liraglutide vs. placebo (P > 0.05 for all events; Table 5).

|

All patients (N = 247) |

Liraglutide (N = 123) |

Placebo (N = 124) |

P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any event of interest (anticipated disease-related, severe hypoglycaemic, or hyperglycaemic) | 65% (160) | 67% (83) | 62% (77) | 0.38 |

| Any anticipated disease-related event | 59% (146) | 64% (79) | 54% (67) | 0.10 |

| Arrhythmia | 15% (36) | 19% (23) | 10% (13) | 0.07 |

| Sudden cardiac death | <1% (1) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | 0.75 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1% (3) | 2% (2) | 1% (1) | 0.43 |

| Worsening heart failure | 41% (102) | 44% (54) | 39% (48) | 0.41 |

| Cerebrovascular event | 3% (8) | 3% (4) | 3% (4) | 0.86 |

| Venous thrombo-embolism | 2% (5) | 1% (1) | 3% (4) | 0.29 |

| Light-headedness, pre-syncope, or syncope | 16% (39) | 17% (21) | 15% (18) | 0.58 |

| Worsening renal function | 12% (30) | 15% (19) | 9% (11) | 0.11 |

| Any severe hypoglycaemic event | 6% (14) | 5% (6) | 6% (8) | 0.59 |

| Hyperglycaemic event | 16% (39) | 12% (15) | 19% (24) | 0.12 |

| Any serious adverse event through Day 180 | 19% (47) | 17% (21) | 21% (26) | 0.44 |

| Any event of interest or serious adverse event through Day 180 | 69% (170) | 69% (85) | 69% (85) | 0.93 |

| Any serious adverse event through Day 210 | 20% (49) | 18% (22) | 22% (27) | 0.44 |

- * P-values based on likelihood ratio χ2 or Fisher's mid-P.

Discussion

Liraglutide is approved by the FDA for chronic weight management in patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 with weight-related co-morbidity.5 However, patients with HF were excluded from most of the trials evaluating liraglutide as a weight loss agent.3, 4 In this on-treatment analysis of the FIGHT study, which enrolled patients with a recent HF hospitalization who have EF ≤ 40%, we identified the following major findings: (i) liraglutide was associated with a significantly greater reduction in weight; (ii) liraglutide was associated with greater control of HbA1c and triglyceride levels; and (iii) there was no difference in the likelihood of adverse events among patients receiving liraglutide compared with placebo. This study has significant findings including that liraglutide reduces weight among patients with advanced HF over 6 months while demonstrating improvements in HbA1c and greater reductions in triglyceride levels.

Several trials have evaluated the role of liraglutide for chronic weight management and metabolic control in overweight or obese patients. The Satiety and Clinical Adiposity: Liraglutide (SCALE) Diabetes trial randomized 846 patients with type 2 diabetes on oral hypoglycaemics and BMI ≥ 27.0 km/m2 to 3.0 mg of liraglutide, 1.8 mg of liraglutide, or placebo.3 Liraglutide was associated with a significant reduction in weight compared with placebo [treatment difference of liraglutide (3.0 mg) vs. placebo −4.0%; 95% CI −5.10, −2.90; liraglutide (1.8 mg) vs. placebo −2.7%; 95% CI −4.00%, −1.42%; P < 0.001 for both]. In the SCALE Obesity and Pre-diabetes trial, 3731 patients who did not have type 2 diabetes but had a BMI of ≥30 or ≥27 kg/m2 and dyslipidaemia or hypertension were randomized 2:1 to 3.0 mg liraglutide or placebo.4 At 56 weeks, patients on liraglutide lost a mean of 18.5 lbs while patients on placebo lost 6.2 lbs (mean difference of −12 lbs; P < 0.001). HbA1c and triglyceride levels also improved among patients randomized to liraglutide. While more modest weight loss was observed in FIGHT (−4.0 lbs treatment difference between liraglutide and placebo), the peak dose of liraglutide was only 1.8 mg and the treatment duration was up to 180 days in FIGHT, compared with 392 days in the SCALE Diabetes and SCALE Obesity and Pre-diabetes trials. In addition, the SCALE Diabetes and SCALE Obesity and Pre-diabetes trials included a background of lifestyle modification intervention, which was not included in FIGHT.

The FIGHT study also significantly differed from prior liraglutide weight loss and cardiovascular safety trials by enrolling a patient population at high risk for cardiovascular events and death. In the SCALE Obesity and Pre-diabetes trial, patients with HF and NYHA class ≥ II were excluded.4 The Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of the Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial randomized 9380 patients with a history of cardiovascular conditions including chronic HF with NYHA Class II or III.9 The number of patients with HF in the LEADER trial was greater than the FIGHT study (14% of the trial population, n = 1350), and there did not appear to be any signal of adverse outcomes in this subgroup9; however, patients in the FIGHT study were a higher risk cohort as they were required to have a recent HF hospitalization at trial entry and a severely reduced EF. The EF data in the LEADER trial was unknown. Our analysis provides unique insights to the impact of liraglutide vs. placebo in a high-risk population of patients with low EF.

Liraglutide demonstrated favourable metabolic control compared with placebo, as reflected by a significant reduction in HbA1c and triglyceride levels. Beyond metformin, current clinical practice guidelines do not provide any significant guidance on therapies for glycaemic control in patients with advanced HF.10-12 Given the differences in the potential underlying mechanisms between patients with HF and diabetes, evaluation of commonly used antihyperglycaemic therapies such as GLP-1 receptor antagonists in this patient population is warranted.13 Our results have significant implications as recent studies have not evaluated the efficacy of anti-diabetic agents for glycaemic control among patients with advanced HF.3, 4, 13-16

Despite the observation of weight loss and favourable glycaemic control associated with liraglutide in our analysis, the clinical implications remain unclear. In the LEADER trial, liraglutide was associated with a reduction in cardiovascular death (vs. placebo; hazard ratio 0.78; 95% CI 0.66, 0.93; P = 0.007). However, in the LIVE trial, liraglutide was associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiac events (including ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, acute coronary syndrome, and worsening HF; 12 with liraglutide vs. 3 with placebo; P = 0.04).17 Our results did align with the finding in the LIVE trial that demonstrated that liraglutide treatment was associated with a weight loss of 2.2 ± 3.1 kg compared with placebo (0.0 ± 3.0 kg) (mean difference −2.2 kg; P < 0.0001). Furthermore, HbA1c was significantly reduced in the liraglutide arm compared with placebo (mean difference −0.4%; P < 0.0001).17

Despite the challenges of identifying HF events in a high risk population,18 concern was raised regarding a possible increase in HF risk among patients with a higher BMI.19 A subgroup analysis of the FIGHT study demonstrated a trend towards increased risk of HF hospitalization in patients with a BMI greater than the median.20 Our analysis suggests that patients above and below the median BMI experience similar weight loss with liraglutide. These results suggest a possible discordance between weight loss and clinical outcomes in patients with HF who have a higher BMI. An obesity paradox has been demonstrated among patients with HF, and unexpected weight loss among patients with chronic HF is associated with an increased risk of death21, 22; this risk extends to obese patients with HF.22 Prior analyses have also suggested that weight loss may decrease arterial stiffness23 and weight gain may be associated with increased ventricular stiffness.24 However, the obesity paradox does not appear to be present in patients with HF and diabetes.25 Overall, the association between intentional weight loss in patients with HF and reduced EF (HFrEF) has been largely unexplored. Given the rising obesity epidemic globally, adequately power cardiovascular outcomes studies are needed to evaluate the potential benefit or harm of behavioural and pharmacologically induced weight loss among patients with HFrEF.

In the primary intention-to-treat analysis, while liraglutide was not statistically associated with weight loss, compared with placebo, the trend towards a reduction in weight was clearly evident (−1.5 kg with liraglutide vs. +0.3 kg with placebo; treatment effect −1.8 kg; P = 0.09). Similar trends are seen among changes in triglycerides associated with liraglutide (15 mg/dL with triglyceride vs. 39 mg/dL with placebo; treatment effect −22 mg/dL; P = 0.08). The use of an on-treatment analysis likely resulted in the differences between our present results and the intention-to-treat analysis. Our results suggest that patients who were able to reach the target dose of liraglutide had the greatest degree of weight loss. Because only 69% of our patients in the liraglutide arm reach target dosing before the last visit used in our analysis, the impact of liraglutide and weight loss may have been underestimated.

Current HF guidelines do not provide any guidance on whether weight loss is beneficial or whether pharmacological therapies should be used.11 Liraglutide mediates weight loss mainly by reducing appetite and caloric intake, rather than increasing energy expenditure.26 Heart failure is associated with significant catabolism and reduction in lean muscle mass27; furthermore, patients with HF are frequently nutritionally deficient.28 While limiting nutritional intake would be a reasonable method of weight loss for an obese patient without HF, we speculate that such strategies in a patient with HF may ultimately lead to adverse outcomes; multiple observational studies have demonstrated the adverse relationship between low BMI and increased risk of cardiovascular outcomes.11 More data will be required to ascertain the relationship between intentional weight loss and outcomes in patients with HFrEF. While this was a post hoc analysis with short follow-up to assess a relationship between weight loss and clinical outcomes, further studies will be needed before liraglutide can be recommended as an agent for chronic weight management in patients with advanced HF. While the absolute weight loss from baseline to last study follow-up associated with liraglutide was not as evident among patients with a BMI greater than or equal to the median, statistically, BMI did not modify the relationship between study treatment and weight loss.

There is a lack of high-quality randomized clinical trial evidence on whether patients with HF should pursue weight loss as a strategy to improve outcomes. Future randomized controlled trials among patients with advanced HF should evaluate whether weight loss—through a combination of physical activity, lifestyle modification, and pharmacological treatment—would improve patient centric outcomes such as symptomology, quality of life, time spent outside the hospital, and functional status. Furthermore, these studies should evaluate the safety of weight loss with regard to mortality given the signals of harm seen in observational studies.

Limitations

These results are subject to the limitations of a post hoc analysis. The present analysis was limited to patients who were ‘on-treatment’ and were present for at least one follow-up visit on study medication; this subgroup may not be reflective of the overall trial population, and results may not be generalizable to the broader population of patients with HF. Weight assessment becomes inherently challenging in the context of fluid and volume retention among patients with HF; our analysis addressed this by adjusting for a congestion score and NT-proBNP. We did not assess clinical outcomes because of the short duration of follow-up and limited number of events in the ‘on-treatment’ analysis. This analysis also was not specifically powered to detect difference in weight among the treatment arms. Our study also had important strengths. Namely, as the FIGHT study enrolled a high-risk patient population excluded from almost all other anti-diabetic drug trials, our results provide unique insights into the efficacy of liraglutide as a weight loss agent.

Conclusions

Among patients with a recent hospitalization for HF and an EF ≤ 40%, treatment with liraglutide was associated with a significant reduction in weight independent of signs and symptoms of HF and NT-proBNP levels at baseline. In addition, liraglutide facilitated favourable metabolic changes not observed in untreated controls. Neither BMI nor the presence of diabetes mellitus modified the relationship between liraglutide and weight loss. These findings provide a basis for a further exploration of the safety and efficacy of liraglutide as an adjunct for weight loss in overweight and obese patients with HF in a well-powered cardiovascular outcomes trial.

Conflict of interest

A.S. reports receiving support from Bayer-Canadian Cardiovascular Society, Alberta Innovates Health Solution, a European Society of Cardiology young investigator grant, Roche Diagnostics, and Takeda. A.D. reports receiving research support from the American Heart Association, Amgen, and Novartis and serving as a consultant for Novartis. K.B.M. reports receiving research grant support from Merck, Sharp and Dohme, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, and Biosense Webster and serving as a consultant for Janssen, Luitpold, and GlaxoSmithKline. G.M.F. reports receiving research support from NHLBI, AHA, Novartis, Amgen, Merck, and Roche Diagnostics and serving as a consultant for Novartis, Amgen, BMS, GSK, Myokardia, Medtronic, Cytokinetics, Stealth, and Alnylam.

Funding

The FIGHT study was supported by grants U10 HL084904 (awarded to the coordinating centre) and U01 HL084861, U10 HL110312, U10 HL110337, U10 HL110342, U10 HL110262, U10 HL110297, U10 HL110302, U10 HL110309, U10 HL110336, and U10 HL110338 (awarded to the regional clinical centres) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The study drug (liraglutide) and matching placebo injections were supplied by NovoNordisk Inc.