The “Young Athlete Body Project”—A pilot study evaluating the acceptability of and results from an eating disorder prevention program for adolescent athletes

Abstract

Background

The high frequency of eating disorders (EDs) in sports speaks of a need for early-stage preventive measures.

Objectives

This study evaluated the acceptability of an age, sex, and sports adapted version of the “Body Project” and changes in mental health symptoms.

Methods

This noncontrolled pilot study included a class of athletes from 18 sports (N = 73, 13–14 years) at a sport-specialized junior high school in six small-group workshops. We interviewed 34 athletes on program acceptability, and all athletes responded to questionnaires at pretest, posttest, and 6-month follow-up including the Body Appreciation Scale 2–Children, Social Attitudes towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 revised, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short form-12 modified, and questions about body appearance pressure (BAP).

Results

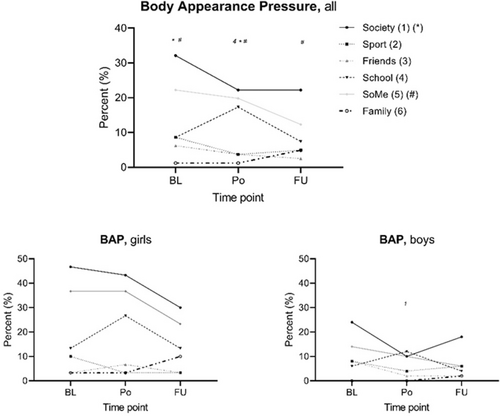

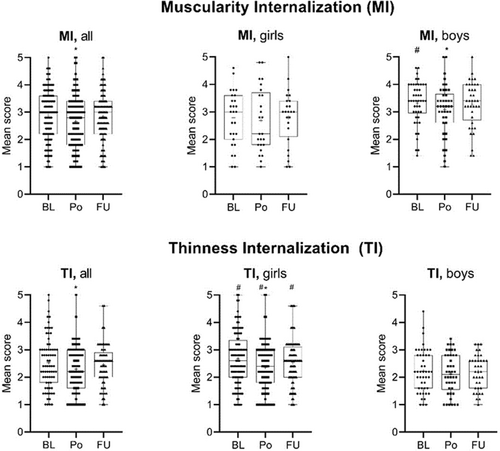

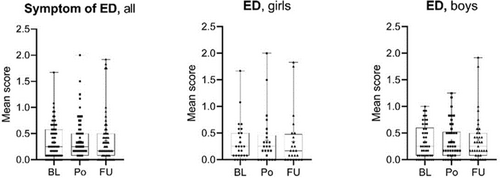

Athletes found the program acceptable and beneficial, but some missed physically oriented activities or did not identify with the focus, particularly boys. There were acceptable levels in mental health constructs before the workshops. There were temporary changes in the percentage of boys experiencing “BAP in society” by −14.8% points (95% CI: −.6 to .0, p = .04), % in total group experiencing “BAP at school” by +11% points (95% CI: .0–.2, p = .05), thinness idealization by girls (g = .6, p = .002) and total group (g = .4, p = .006), and muscularity idealization by boys (g = .3, p = .05) and total group (g = .23, p = .04).

Discussion

Athletes experienced benefits from the Young Athlete Body Project. Seeing stabilization in outcomes may mean a dampening of the otherwise expected worsening in body appreciation and ED symptoms over time.

Public Significance

Adolescent athletes are at risk for developing EDs. Due to lack of prevention programs for this group, we adapted and evaluated a well-documented effective program, the Body Project, to fit male and female athletes <15 years. The athletes accepted the program and experienced participation benefits, with stronger acceptance among girls. Our promising findings encourage larger scaled randomized controlled trials to further evaluate a refined version this program among very young athletes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the past three decades, consistent documentation has revealed a two to three times higher prevalence of disordered eating and eating disorders (EDs) among elite-level athletes (aged ≥16 years) in comparison to the general population (Bratland-Sanda & Sundgot-Borgen, 2013; Herpertz-Dahlmann, 2015; Keski-Rahkonen & Mustelin, 2016; Martinsen & Sundgot-Borgen, 2013).

1.1 ED risk factors in adolescent athletes

Although limited evidence exist on adolescent elite-level athletes (aged <16 years), a recent study has indicated a notable level of weight and shape concern within this population (Stornæs et al., 2023). Early specialization in sports and body dissatisfaction are well-known triggers for developing symptoms of EDs in adult competitive athletes (Kontele et al., 2022; Stice & Shaw, 2002; Wells et al., 2020). Thus, we argue that adolescents aiming to become elite athletes are a unique at-risk group. Body dissatisfaction can be a result of encountering body appearance pressure (BAP), stemming from awareness of sport-specific adult body ideals, heightened body appearance awareness due to snug uniforms, or BAP as a result of exposure to the prevailing nonathlete body ideals beyond their sport context (e.g., social media) (Godoy-Izquierdo & Díaz, 2021; Jagim et al., 2022; Stoyel et al., 2021; Teixidor-Batlle et al., 2020; Wasserfurth et al., 2020). In addition, the unrealistic expectations of rapid muscle growth in boys, and the natural pubertal shifts in body composition influencing optimal sports performance, especially in weight-sensitive and leanness-focused sports, may additionally challenge body appreciation in adolescent elite-level athletes (Bergeron et al., 2015).

During adolescence, boys and girls show increased self-evaluation, physical comparisons, and internalization of societal ideals. Thus, navigating the various unrealistic body ideals can pose a particular challenge (Littleton & Ollendick, 2003).

The high risk of EDs among older adolescent competitive athletes and the exposure to well-known risk factors in the younger age group of athletes highlights the importance of exploring the effects of ED prevention programs aimed at young adolescents of all genders engaging in various sports.

1.2 ED prevention in adolescent athletes

The frequent use of social media among adolescents (Meier & Gray, 2014; Rodgers et al., 2020; Rousseau, 2021) and experience of appearance pressure from the media (Baceviciene & Jankauskiene, 2020) are associated with stronger internalization of appearance ideals among boys and girls. Improving media literary has proven effective in mitigating these mechanisms, consequently reducing the risk of body dissatisfaction and risk of ED development (Wilksch, 2019). Moreover, cultivating a robust body appreciation can act as a buffer against the effects of BAP (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015) and should be actively encouraged among young elite athletes (Mountjoy et al., 2018).

The original Body Project (BP) is a selective ED prevention program, which is based on cognitive dissonance theory. The program addresses and challenges body appearance idealization through workshop activities to improve resistance against body ideals and prevent body dissatisfaction among participants (Stice, Shaw, et al., 2008). Although previous successful programs have been developed for young female athletes, few have been replicated and evaluated over time within different groups (Sick et al., 2022). The BP has proved effective in reducing body dissatisfaction, thinness internalization, and ED symptoms, as well as future ED onset in young females (>15 years of age) with self-reported body dissatisfaction (Stice et al., 2006; Stice, Marti, et al., 2008). In the recent years, adaption of the program to groups at high risk of EDs such as female college athletes and professional dancers, and more recently male athletes, at age ≥17 years, have proved to be similarly effective (Gorrell et al., 2021; Perelman et al., 2022; Stewart et al., 2019). Nevertheless, there is a gap in our knowledge relating to how well the BP may prevent similar challenges in a younger and broader athlete sample, before any manifestation of body dissatisfaction or onset of EDs. Thus, our goal was to evaluate whether an adapted version of the BP for this population may prove useful in primary prevention of body image concerns and eating pathology.

The aims of this pilot study were to (1) evaluate the acceptability of the BP adapted to male and female adolescent competitive athletes (the Young Athlete Body Project); (2) explore body appreciation, BAP, internalization of body ideals, and frequency of ED symptoms in young adolescent competitive athletes of both sexes; and (3) evaluate immediate and longer term within-subject changes after participation in the program on these same mental health constructs.

2 METHODS AND MATERIALS

This noncontrolled pilot study ran during the autumn of 2022 at one specialized sport junior high school in Norway. Here, pupils (further referred to as “athletes”) enroll with the intention to become top elite-level athletes, and the school structure aims to facilitate such progression. The principal and a group of teachers participated in the project planning and implementation of the program. All athletes, boys and girls, attending ninth grade (13–14 years) participated in the program “Young Athlete Body Project” as it was held during obligatory school hours. Athletes were only included in data collection and analyses if they and both parents signed an informed consent.

2.1 The Young Athlete Body Project

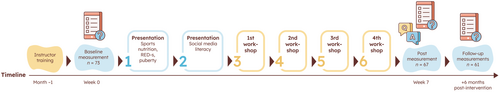

The program is a sports-, age-, and sex-adapted version of the BP, adjusted to fit as a school-based prevention program, held weekly during school hours through six continuous weeks (Figure 1). As both general and sport-specific pressures regarding body appearance are addressed, the original manual also underwent modifications to incorporate sport-related and age-adapted language and cases. The adapted version incorporates two additional school class-based interactive educational sessions held before the four original workshop sessions. These educate on (1) sport-specific energy requirements, biological maturation, and low energy availability and (2) media literacy (Table 1). Groups were split by sex to create a safe environment for personal sharing and for athletes to uninhibited discuss more sex-specific challenges. Adaptation and content are described in detail in Supplementary File 1.

| Topics and activities | Assignments | |

|---|---|---|

Educational session 1 60 min |

Sport-specific energy requirements. Biological maturation and performance. Adverse outcomes from low energy availability. Activity: Digital polls. |

|

Educational session 2 60 min |

Media literacy; social media mechanisms, retouching, source criticism. Body talk. Activity: Pair-reflections and class discussions. |

|

Workshop 1 60 min |

Topic: What are general and sports specific body ideals, where do they originate from, what are the typical perceived and communicated benefits from adhering to the body ideal, what are the actual negative consequences from trying to adhere. Activity: Reponses to open questions, reflections, and suggestions. |

(1) Write a letter to a fellow athlete who you think may struggle with body dissatisfaction and express your worries and address the negative consequences as an adolescent and as an athlete by trying to change one's appearance. (2) Make a top-5 list of characteristics you appreciate with yourself. |

Workshop 2 60 min |

Topic: How can we reduce body idealization in general and within sports; how can we argue against such focus. Activity: Role-play inviting to argue against body appearance focus/talk. |

(1) Write a short letter (a) to someone who challenged your self-esteem or (b) to your own sport environment on how to better promote body acceptance. (2) Top 5-list: Body activism activity examples. |

Workshop 3 60 min |

Topic: Continuation from Workshop 2. Activity: Role-play and quick identification and inhibition of body appearance focus/talk. |

(1) Identify three scenarios of upward comparison and suggest how to reduce such comparisons. (2) Social media, either (a) post body activism on social media, or (b) argue against appearance focus on social media, or (c) be critical about social media in a text, or (d) critically evaluate your social media accounts. |

Workshop 4 60 min |

Topic: General and sports-related comparison, social media, and program debrief. Activity: Group discussion on self-esteem promotion and positive social media activities. Discussion on program experiences. |

(1) Motivating to practice the top-5 list of activities to reduce body appearance focus and to make more fellow athletes happy about themselves. |

2.2 Outcomes

2.2.1 Qualitative measures

To explore program acceptability, the young athletes were invited to participate in focus group interviews postprogram (week seven, see Figure 1). In total, 34 athletes agreed to participate in focus group interviews. Female program instructors led the interviews lasting 12–18 min with groups of five to six athletes each (six groups in total, divided by sex). The aim was to understand how athletes experienced the session topics, program delivery, and total program acceptability, including experience of benefits, gains, or harm (Supplementary File 2).

Program acceptability was additionally evaluated in the posttest questionnaires through open- and closed-ended questions (Supplementary File 3).

2.2.2 Quantitative measures

Athletes self-reported biological sex, body weight, height, and sports specific characteristics. To measure mental health symptoms, athletes responded to digital questionnaires at baseline, postintervention, and 6 months postprogram (Supplementary File 3).

Body Appreciation Scale 2–Children (BAS-2C) measures body appreciation through 10-items, with response option ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Higher average score indicates higher levels of body appreciation (Halliwell et al., 2017). Perceived BAP was measured by questions developed by the research group (Mathisen et al., 2020; Sundgot-Borgen et al., 2021) asking the respondents to rate their experience of pressure on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (no experienced pressure) to 4 (very high experience of pressure), and in analyses dichotomized to experiencing low (1–2) or high levels of pressure (3–4) within specified contexts (society, school, sport, friends, social media, family). Social Attitudes towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 revised (SATAQ-4R) measures internalization of the thin and muscular/athletic body ideal (Schaefer et al., 2017). Response options range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The project group modified the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short form-12 modified (EDEQ SF-12 modified) to measure ED symptoms in the young athlete sample (for details, see Supplementary File 3). Similar to the original version, items are responded to on a Likert-scale ranging from 0 to 3 (Gideon et al., 2016; Gideon et al., 2018). Internal consistency within scales was acceptable with Cronbach Alphas ranging from .76 to .95.

2.3 Ethics

The project is approved by the Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research ethics (ID-number 277766), and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (ID-number 149662) and preregistered in the Clinical Trials registration system (ID-number NCT05583162).

3 ANALYSES

Qualitative interviews were thematically analyzed by one author following the stepwise process as suggested by Braun and Clarke (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Braun & Clarke, 2019): transcribing and familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes for the data, identifying, and reviewing themes by collated codes, naming themes, and producing the report. During the final stage, rich extracts were chosen to illustrate themes.

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics v.28.0.1.0. To explore status and evaluate sex difference in demographic and outcome variables, we used independent sample t-tests and chi-square tests for numerical and categorical data, respectively. Linear mixed regression models were constructed to investigate temporal within-group changes and discern potential variations between genders. Standard errors were calculated using the restricted maximum likelihood function. To address dependence in the repeated outcome measures, a random intercept factor was incorporated. The fixed factors comprised time, sex, and the time × sex interaction. A p-value of ≤.05 was chosen. Hedges' g (g) effect sizes for numerical data, with effect sizes defined as small, medium, and large at a level of g = .2–.5, .5–.8, and >.8 and φ = .1, .3, and .5.

4 RESULTS

From a total of 90 athletes, 73 consented to participate, with 67 (74%) and 61 (68%) responding to the post- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires, respectively. Participant demographics are presented in Table 2.

| Total (N = 73) | Boys (N = 46) | Girls (N = 27) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/sum | 95% CI/% | Mean/sum | 95% CI/% | Mean/sum | 95% CI/% | Mean diff | 95% CI | p value | g | |

| Age, years | 13.9 | 13.8 to 14.0 | 13.9 | 13.8 to 14.0 | 13.9 | 13.7 to 14.0 | −.0 | −.2 to .9 | .497 | .0 |

| BMI, kg × m−1 | 19.2 | 18.8 to 19.7 | 18.9 | 18.4 to 19.4 | 19.7 | 18.9 to 2.6 | .8 | −.1 to 1.7 | .090 | .4 |

| Training hours per week, total | 17.3 | 16.3 to 18.4 | 17.7 | 16.3 to 19.3 | 16.7 | 15.3 to 18.1 | −.9 | −3.0 to 1,3 | .391 | .2 |

| BAS-2C | 4.2 | 4.1 to 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.1 to 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.9 to 4.4 | .2 | −.1 to .5 | .270 | .3 |

| BAP society | 1.1 | .9 to 1.3 | 1.0 | .7 to 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.0 to 1.7 | −.4 | −.8 to .0 | .055 | −.5 |

| BAP school | .6 | .4 to .8 | .6 | .4 to .8 | .7 | .4 to 1.0 | −.1 | −.5 to .2 | .466 | −.2 |

| BAP sport | .5 | .3 to .6 | .5 | .3 to .7 | .4 | .2 to .7 | .0 | −.3 to .3 | .854 | .2 |

| BAP friends | .5 | .3 to .6 | .4 | .3 to .6 | .6 | .3 to .8 | −.1 | −.4 to .2 | .377 | −.3 |

| BAP social media | .8 | .7 to 1.0 | .5 | .3 to .8 | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.7 | −.8 | −1.2 to −.5 | <.001 | −1.2 |

| BAP family | .1 | .0 to .3 | .1 | −.1 to .2 | .2 | .1 to .4 | −.1 | −.4 to .1 | .229 | −.3 |

| SATAQ T | 2.6 | 2.4 to 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.0 to 2.5 | 3.1 | 2.8 to 3.4 | −.8 | −1.2 to −.4 | <.001 | −.9 |

| SATAQ M | 3.1 | 2.9 to 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 to 3.6 | 2.8 | 2.4 to 3.1 | −.6 | .0 to 1.0 | .011 | .7 |

| EDEQ global | .4 | .3 to .4 | .4 | .2 to .5 | .4 | .2 to .5 | −.0 | −.2 to .2 | .898 | .0 |

| Sport type | ||||||||||

| Team, n (%) | 42 | (57.5%) | 28 | (6.9%) | 14 | (51.9%) | - | - | ||

| Endurance, n (%) | 9 | (12.3%) | 4 | (8.7%) | 5 | (18.5%) | - | - | ||

| Alpine and Snowboard, n (%) | 8 | (11.0%) | 7 | (15.2%) | 1 | (3.7%) | - | - | ||

| Racket, n (%) | 7 | (9.6%) | 4 | (8.7%) | 3 | (11.1%) | - | - | ||

| Aesthetic or weight class, n (%) | 6 | (8.2%) | 2 | (4.3%) | 4 | (14.8%) | - | - | - | |

| Power, n (%) | 1 | (1.4%) | 1 | (2.2%) | 0 | (.0%) | - | - | - | |

- Note: Sports included in each sport type: Team sports (soccer, handball, ice hockey, bandy, basketball), endurance sports (cross-country skiing, biathlon, swimming, cycling), alpine and snowboard (alpine, snowboard), racket sports (tennis), aesthetic or weight class sports (dance, athletics, gymnastics, karate, judo), and power sport (cross-fit). Mean diff: Mean difference between groups compared. Hedges' g: g. A p-value of ≤.05 is considered statistically significant in comparisons between boys and girls. Bold format is highlighting significant p-values

- Abbreviations: BAP, body appearance pressure; BAS, Body Appreciation Scale-2C for children; CI, confidence interval; EDEQ, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short form-12 modified; M, Muscularity subscale; SATAQ: Social Attitudes towards Appearance Questionnaire; T, Thinness subscale.

Attendance to the six program sessions was 61 (93.8%), 64 (97%), 57 (87.7%), 62 (95.4%), 54 (87.1%), and 60 (89.6%), respectively.

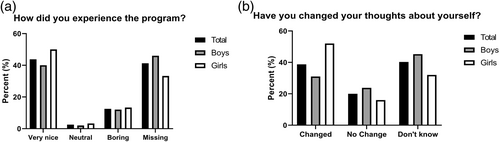

4.1 Questionnaire-assessed experience of the program

Of 67 participants at posttest, 47 responded to the open-ended question regarding program experience. Here, 35 athletes gave feedback that were categorized and further summarized to indicate a positive and constructive program experience (Figure 2a). For the closed-ended question, 26 reported yes to having in various ways changed their thoughts about themselves after program participation (Figure 2b). In the associated follow-up question allowing for further elaboration, many reported to have improved their self-image and body satisfaction and specifically increased awareness of how social media affects them. They found the group discussions very informative by understanding the shared experience of BAP. Still, three athletes reported negative feelings toward the program, mentioning feeling conflicted about potentially sacrificing their training to attend the sessions, or to have altered their awareness of body appearance and thoughts about foods and eating.

4.2 Interview assessing the acceptability of the program

Overall, it seemed evident from the focus group interviews that girls, more frequently than boys, expressed satisfaction and appreciation for the program. Still, some interindividual nuances were clear. Overall, the results may be sorted by three themes; “on repeat—for the better and the worse”, “lowering the barrier”, and “make it understandable”.

4.2.1 “On repeat—for the better and the worse”

No, not really much of an issue for me [body appearance pressure]. I don't struggle much with it, so I don't think about it, really.

Boy, focus group 1.

But it's a good thing that we get to learn how others are doing. So yeah, even though we don't feel that way ourselves, we sort of get an insight into how others are doing.

Boy, focus group 1.

And then we had the assignments, which made me work a little more with my own perception and feelings, like when you were asked to write those positive things about yourself. Or when we were to write a letter about these things, well, then you actually had the opportunity to really think about it.

Girl, focus group 3.

4.2.2 “Lowering the barrier”

“It would be completely different if the boys were present. I wouldn't have said anything, or I would have said something completely different, ‘cause—it was kind of much like… We talked a lot about the boys, and you couldn't kind of tell it TO the boys”.

Girl, focus group 3.

The delivery of the program by external experts was important for attention, engagement, and personal sharing. Interestingly, being a stranger held more significance than being an expert. Although some athletes had trust in their teachers, many pointed out the challenge of sharing personal thoughts and feelings with their teacher due to the long-term relationship and interactions they would continue to have in various contexts.

“I experienced it as a good thing [the assignment]. A bit like the other girl said, to say things about yourself without feeling self-precious, and specifically when we were to write a letter to a person that had said things that hurt you. I did that. Or—I wrote a rather personal letter, and I actually think it was nice to share my thoughts about it.”

Girl, focus group 4.

“And it's kind of… well, I don't know… You automatically get a bit more honest with yourself, because there are things you don't find easy to talk about when you are to say it in a group, but if you write it on a note, then you have to be all honest.”

Boy, focus group 2.

“Yes, it was a lot of topics that were like… I kind of feel like; you are thinking about it, but perhaps don't speak up about. And then it is nice to, like, that all of us—when all have been involved and talked about it, then all know about these topics, right?”

Girl, focus group 3.

“Yes, and the role-plays—it was a bit fun when you kind of figured out that it is not that difficult or scary to speak against others”.

Girl, focus group 3.

“I feel like, the way you talk to others, also affects yourself, like such comments, so I try not to say too much about appearance and such alike.”

Boy, focus group 6.

“I notice that after participating in this program, you pay more attention to others—that you do not want anything to happen to them, so you kind of get better to say positive things to them.”

Boy, focus group 2.

Lastly, within the theme of “lowering the barriers”, there was a focus on mitigating personal risks related to body dissatisfaction and low self-esteem while developing new coping mechanisms and strategies for self-empowerment. Some boys reported no personal change in feelings or behaviors but acknowledged the potential benefits for others or found value in gaining insight into others' experiences. Many athletes found significant meaning in practicing acknowledging positive aspects about themselves. Similar benefits were observed from the realization that genetics and developmental age play crucial roles in performance and appearance.

“An example of what has changed; as I now kind of use social media, I do not see anything about… ‘cause we had this challenge to unfollow all that contributed with body appearance pressure, so now I kind of don't think about it at all. And this is what one wants to achieve.”

Girl, focus group 3.

“It has made me more aware of…for example, that much in social media is edited. I knew it was edited, but not this much. So, it has made me more aware on what is for real and what is not”.

Boy, focus group 1.

4.2.3 “Make it understandable”

“And more about how you can change your body in healthy ways, because there are many that want to become thinner. But they do it in unhealthy ways. You could get thinner and still be healthy.”

Boy, focus group 5.

“Yes, I felt that you—you actually addressed training as something negative. Because we had those role-plays (talking against appearance related comments) arguing against sayings like—yes, I want to look like Ronaldo—… ‘cause you DO want that! There is like no one that do not want that!”

Boy, focus group 5.

4.3 Acceptability of responding to the questionnaires

After the 6-week program, 52% of girls and 38.1% of boys felt that responding to the questionnaire was a positive and meaningful experience. Furthermore, 40% of girls and 26.2% of boys were neutral about it, and 8% of girls and 31% of boys found it boring. Additionally, two (4.8%) of the boys reported it to be negative and triggering for intrusive thoughts.

4.4 Body appreciation, body appearance pressure, internalization, and ED symptoms

Table 2 presents baseline values for mental health construct outcomes. Girls reported higher levels of BAP from social media than boys (g = .9, p = <.001). At baseline, girls internalized the thin ideal more (g = .9, p < .001) and the muscular ideal less (g = −.7, p = .011), versus boys.

4.5 Changes in body appreciation, body appearance pressure, internalization, and ED symptoms over time

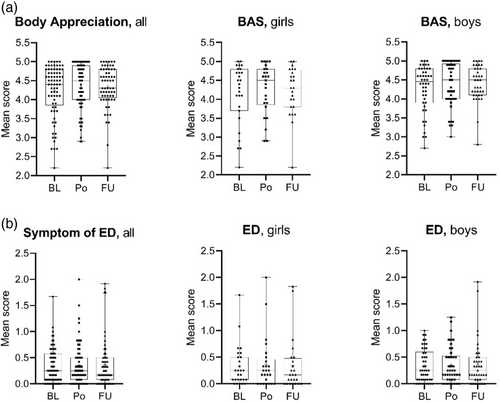

A high baseline mean score in BAS (Figure 3) did not change any further after program participation, neither within the total group nor in boys or girls separately.

Significantly more girls than boys reported to experience “BAP in society” at baseline (p = .003) and postintervention (p = .001) (Figure 4). Only in boys the percentage who reported to experience “BAP in society” was temporarily reduced postintervention with an estimated mean reduction of −14.8% points (95% CI: −.6 to .0) (p = .04). There was a temporary increase in the percentage who reported experience of “BAP at school” in the total group with an estimated mean increase of 11% points (95% CI: .0–.2) (p = .05), with no difference between sexes. At all time points, more girls than boys reported “BAP social media” (p < .05), but no significant change was observed over time for either sex (Figure 4).

The baseline difference between sexes in thinness idealization was evident at all time points (p < .02). A temporary significant reduction in thinness idealization in girls (g = .6, p = .002) was accompanied by a similar change in the total group (g = .4, p = .006) at posttest (Figure 5). Similar temporary change was evident for muscularity idealization in boys (g = .3, p = .05) and total group (g = .23, p = .04). Generally low scores in EDEQ did not change over time, and there were no sex differences (Figure 6).

5 DISCUSSION

This pilot study explored the acceptability of the Young Athlete BP, an intervention for young athletes aimed at improving body appreciation, and reducing BAP, body ideal internalization, and ED symptoms. Acceptance for and perceived benefit of program participation were highly rated. Temporary reductions in body ideal internalization were evident following program participation, and although the society emerged as the most prominent source of BAP within the group, the observed changes in BAP overall seemed sporadic and temporary after program participation.

5.1 Acceptability

An encouraging result from this pilot study was the appreciation, acceptance, and perceived benefit of the program. The young athletes had a positive experience of the group-based workshops as they provided a safe space to share thoughts and experiences, and an opportunity to increase collective awareness on important topics. This is supported by the theory of peer influence, which points to the efficient change in beliefs and attitudes when done so within a social learning context (Jones & Crawford, 2006). These experiences can also be understood through the social cognitive theory, suggesting that human behavior evolve through observational learning and social experience, in which people are both influenced by and actively influence their environments (Bandura, 1986). Hence, collectively discussing and challenging unhealthy attitudes, trends, and idealizations has the potential to impact individual athletes by transforming the classroom into a healthier social environment.

Although a few athletes mentioned the repetition of content as monotonous, many athletes specifically mentioned that such elaboration was helpful in reflecting, engaging in, and processing the new learnings.

Although most boys were satisfied with the program, we identified some potential explanations for lack of engagement by those less enthusiastic. In accordance with the original BP, the Young Athlete BP draws on the principles of cognitive dissonance, which has shown promising results among young adolescent girls (Halliwell & Diedrichs, 2014; Rohde et al., 2014) and older adolescent men (Perelman et al., 2022). However, to our knowledge, this has not been explored in adolescent boys. Although speculative, it is tempting to suggest there might be cognitive differences in maturity between girls and boys at this age, possibly influencing how this method resonated with each sex. During group interviews, some of the boys' comments reflected misinterpretation of the aim and focus of the program. Also, there was clear dissatisfaction with how the workshop took time away from training and they preferred “to train rather than to talk”. Furthermore, some participants did not find the topic of BAP highly relevant for them personally, which may cause reduced program activity (Stok et al., 2015). Accordingly, the instructors experienced some difficulties with engaging all athletes in the program, especially the boys.

Another challenge within some workshop groups, regardless of sex, was that many of the discussions needed to be moderated due to statements such as “as long as you work hard, you can look fit” and that “being obese is something everyone can avoid.” These digressions navigated away from the planned workshop topics and may have limited program effect. These beliefs should be addressed in a revised manual.

5.2 Body appreciation, BAP, internalization, and ED symptoms

A novel finding in this study is that the athletes reported acceptable body appreciation and few symptoms of EDs. This is similar to a previous finding in nonathlete adolescents (Moreira et al., 2018), and young athletes (Stornæs et al., 2023) of similar age, but in contrast to what is reported in somewhat older adolescents (>15 years) (Lemoine et al., 2018) and young adults (Sundgot-Borgen et al., 2021). Interestingly, although we did not see any sex difference in our young sample, girls reported significantly lower body appreciation compared with boys in an older adolescent sample (Lemoine et al., 2018) and among young adults (Sundgot-Borgen et al., 2021). Also, the lack of sex differences in ED symptoms in early adolescents is interesting, mirroring previous findings in nonathlete (Moreira et al., 2018) and athlete (Stornæs et al., 2023) samples. In contrast, a study on older adolescent high school athletes found more ED symptoms among girls than boys (Martinsen & Sundgot-Borgen, 2013). Together, these findings may support that body appreciation and body dissatisfaction changes with puberty and age and also parallel onset of first ED symptoms at age 14–16 years. This also gives preliminary support for early intervention to hinder the disadvantageous reduction in body appreciation and possibly the risk of developing an ED.

Interestingly, participants in the current study reported levels of internalization of the thin and muscular body ideals that are comparable to both younger (12.5 years) and older (17 years) nonathlete adolescents (Schaefer & Thompson, 2014; Sundgot-Borgen et al., 2020). This suggests that changes in internalization of body ideals as a risk for EDs, compared with body appreciation and symptoms of EDs, occurs at an earlier age. A longitudinal design is needed to explore this further. Still, these findings point to the importance of increasing the young individuals' ability to resist external appearance cues by supporting personal body appreciation and social media literacy. The temporary improvements in body ideal internalization after program participation may find support from the tripartite influence model. This theory suggests that a reduction in body ideal internalization may occur both through changing the classrooms' social norm related to unhealthy ideals and through improving athletes' media literacy (Thompson et al., 1999).

The level of body appreciation, internalization of body ideals, and symptoms of EDs seemed stable over the 6-month follow-up period, but with some interesting temporary improvements in internalization. Although preliminary, this may be an overall positive finding given the expected reduced body appreciation and the increase in body ideal internalization and ED symptoms with increasing age (Lemoine et al., 2018; Schaefer & Thompson, 2014; Sundgot-Borgen et al., 2020; Sundgot-Borgen et al., 2021). The favorable baseline values may also partially explain the smaller within-subject effect sizes than typically reported in standard BP research (a ceiling effect) (Stice et al., 2019), but small effects seem to be a typical finding in those younger than 14 years (Stice et al., 2019). Important differences between the standard BP and the current adapted manual are the latter's more universal nature of the included sample, that is, inclusion regardless of baseline self-reported body dissatisfaction, compared with the standard BP. In contrast, the BP is a selective program targeting older adolescents with self-reported levels of body dissatisfaction (Stice et al., 2020). Aiming to prevent a negative change, rather than improving scores seems like a valuable direction for future studies on similar samples (Kusina & Exline, 2019).

A high percentage of athletes reported “some” or “very much” BAP from the society in general and social media specifically, also reflected by the interviews where athletes expressed a willingness and need to discuss BAP. This underlines the significance of equipping athletes with tools to effectively cope with such pressures and to proactively prevent a further increase in the internalization of unrealistic body ideals in the future.

Additionally, the athletes noted a heightened awareness and discernment of media content, actively choosing to unfollow appearance-related content, which led to a positive transformation in their daily feed, illustrating the empowering impact of media literacy.

The sessions and workshop content focusing on media literacy undeniably played a crucial role. Future studies might want to measure whether media literacy increases due to the program.

5.3 Adverse effects from participation

Although there may be worries that ED prevention programs at a young age might increase awareness on body appearance rather than reduce it, our experience and findings do not support this. Neither did we find any negative outcomes from having adolescents responding to questions about body appearance and eating habits. The two boys that reported increased awareness related to their food intake and body appearance while answering the questionnaire did not report unhealthy scores on any mental health assessment tool. We find it reasonable to assume that these two boys were rather trying to express their dissatisfaction with the program by giving such a concerning vote.

5.4 Strengths and limitations

Study strengths include the novelty of modifying an accepted and effective prevention program to a very young athlete population within a school setting, the inclusion of both boys and girls, the combination of qualitative and quantitative measurements of symptom change and acceptability of the program, and the follow-up assessment. Still, several limitations should be noted. The study lacked a control group, and the small sample size reduced the statistical power, meaning that results should be interpreted with caution. Lack of male instructors may have influenced the involvement by boys and hence possibly the results obtained. Having qualitative interviews led by program facilitators could make participants feel safe but could also influence participants' responses due to participant bias and may potentially influence interview analyses due to researcher bias. Use of interviewers not involved in the program execution is suggested. Validity issues of outcome measurements are relevant, such as the reduced comparability with other studies when modifying the EDEQ short form-12 and possible misinterpretation of questions and short response time by some participants in general. Results suggested that several athletes were not able to differentiate between exercising to perform better as an athlete and exercising primarily to adhere to the more muscular and fit body ideals, potentially leading to false high scores especially on the SATAQ items. One important detail that may explain some of our favorable baseline findings may be the high number of athletes representing team sports and fewer representing endurance and aesthetic sports, as challenges with ED symptoms are more prevalent in weight-sensitive sports (Sundgot-Borgen & Torstveit, 2004).

5.5 Practical implications and future directions

Findings are preliminary, and the observed improvements over time are only temporary. Still, the Young Athlete BP was acceptable and perceived as beneficial by most athletes and could be an important option to the frequent requests and need for prevention programs. The program could potentially aid young adolescent athletes in staying healthy through the most vulnerable years while enjoying their sport. The experiences from this pilot should be used to improve the program, taking into account the participation feedback and important observations mentioned in the limitation section. Specifically, this includes making sure all athletes are prepared and informed about the program focus before initiation. Here, information on the importance of collective program participation, regardless of personal experience of body dissatisfaction, should be emphasized to foster program motivation and engagement. Relevance among boys can be increased by engaging male instructors, and making sure both male and female athletes' perspectives are addressed in the workshop. The boys suggested more varied activities within each workshop. We believe avoidance of training sessions for arranging the program, and rather substitute other school subjects, is one important aspect of this; but more varied content within workshops would also be useful. One such change may be to encourage the athletes to explain and discuss the individual solutions made for each assignment during the following workshop. Also, one social media activism assignment could be conducted in pairs within a workshop instead of between sessions.

We find it reasonable to suggest that a collective awareness of BAP, a better acceptance and understanding of pubertal development, awareness of personal body communication, and improved personal body acceptance may aid in resisting future internalization of unrealistic body ideals. We believe the young athletes became better equipped to navigate away from negative exposures and influences by (1) discussing why idealized bodies are unrealistic; (2) addressing the believed benefits and risks of adhering to body ideals; (3) becoming aware of personal social media use; (4) practicing methods to better control content in personal social media platforms; and by (5) focusing on positive experiences of body appearance and abilities, performance, or personality.

6 CONCLUSION

An age- and sex-specific adapted version of the standard BP for adolescent athletes was found acceptable and appreciated. Levels of body appreciation were high, and symptoms of EDs were low in this young athlete sample, but findings still suggest the presence of body ideal idealization. For most outcomes, we did not see permanent changes, but a stabilization in this age group may be considered successful. Future randomized controlled trials with larger sample size, inclusion of a control group, and a long-term follow-up extending beyond the typical age of ED onset are needed to evaluate a true preventative effect of this more universal program approach.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Christine Sundgot-Borgen: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Line Wisting: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing – review and editing. Jorunn Sundgot-Borgen: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; supervision; writing – review and editing. Karoline Steenbuch: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Jenny Vik Skrede: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Karoline Nilsen: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Eric Stice: Investigation; resources; supervision; writing – review and editing. Therese Fostervold Mathisen: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the efforts with participating as part of the intervention team by Nina Sølvberg, PhD, Aurora Jørnsdatter Kojen, MSc, and Anne Louise Wennersberg, SW. We are also grateful for the help provided by Kethe Svantorp-Tveiten, PhD, with communication and provision of contract with the school.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was provided for this pilot study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.