Comparing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pediatric and family medicine clinicians toward atypical anorexia nervosa versus anorexia nervosa

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the knowledge, attitudes, and current practices of adolescent primary care providers regarding the epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis of atypical anorexia nervosa (AN) compared to AN.

Methods

An online survey was sent to the Pediatric and Family Medicine clinicians who provide medical care to adolescents. Statistical analyses compared differences in responses to questions about atypical AN versus AN.

Results

Relative to AN, participants (n = 67) were significantly less familiar with atypical AN, less likely to consider a diagnosis of atypical AN, less comfortable identifying atypical AN, less likely to counsel patients with atypical AN on health risks, less likely to refer patients with atypical AN to a specialist, and less likely to correctly identify atypical AN. Clinicians with more years in medical practice reported a significantly larger gap in familiarity between AN and atypical AN than clinicians with less than 5 years of practice.

Conclusions

Providers who care for adolescents appear to be less familiar with and less likely to identify atypical AN compared to AN. This knowledge gap may be more pronounced among clinicians with more years practicing medicine due to the novelty of atypical AN as a diagnosis. Lack of knowledge surrounding atypical AN risk factors may result in delayed diagnosis and associated poor health outcomes. Future research should investigate strategies that improve knowledge and screening of atypical AN in medical and other settings.

Public Significance

Pediatric and Family Medicine clinicians are less familiar with atypical anorexia nervosa (AN) and less likely to diagnose a patient with atypical AN relative to AN. Insufficient knowledge about atypical AN may place these individuals at increased risk for worsening restrictive eating and the physical and psychological consequences of malnutrition.

1 INTRODUCTION

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines atypical anorexia nervosa (AN) as an eating disorder wherein “all of the criteria for anorexia nervosa are met, except that despite significant weight loss, the individual's weight is within or above the normal range” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Atypical AN is as common or more common than full-threshold AN (Harrop et al., 2021). Between 2005 and 2010, the percentage of non-underweight adolescents admitted to a medical hospital with restrictive eating disorders increased from 8% to 47% (Sawyer et al., 2016), suggesting a rise in the prevalence of atypical AN. Compared to patients with AN, those with atypical AN are more likely to have a history of being overweight or obese and tend to experience greater weight loss over a longer period of time (Sawyer et al., 2016). Additionally, adolescents with atypical AN have similar, or even more severe, eating disorder-related cognitive disturbances than those with AN (Walsh et al., 2022).

Despite evidence for increased prevalence of atypical AN in adolescents, fewer patients with atypical AN are referred and admitted to eating disorder-specific care in the United States than those with AN (Harrop et al., 2021). This highlights a potential disconnect between epidemiology and clinical practice. This gap becomes even more concerning in view of research indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and re-opening has exacerbated eating disorder symptoms (Hartman-Munick et al., 2022; Monteleone et al., 2021).

Primary care providers often struggle to identify eating disorders before obvious physical changes occur (Sim et al., 2010). In non-underweight patients with eating disorders such as atypical AN, the lack of physical symptoms can be detrimental, as patients can still develop life-threatening bradycardia or electrolyte imbalance (Moskowitz & Weiselberg, 2017). Indeed, hospitalized adolescents with atypical AN or AN who experienced a greater amount, rate, or duration of weight loss had significantly worse medical and nutritional status, independent of their body mass index (BMI) when admitted to the hospital (Garber et al., 2019). Failure to identify atypical AN in adolescents may contribute to increased symptom severity and likelihood for hospitalization.

While it appears that clinicians are less familiar with atypical AN and are less likely to identify atypical AN relative to AN, no study to date has assessed providers' knowledge, attitudes, or practices toward these two groups. We hypothesized that Pediatric and Family Medicine providers who treat adolescents would: report lower knowledge, familiarity, and comfort with atypical AN than AN; be less likely to correctly diagnose adolescents with atypical AN than AN; and be less likely to refer adolescents with atypical AN than AN to specialty services.

2 METHOD

An online questionnaire developed in REDCap was sent via email to 364 Penn State Health Pediatric and Family Medicine attending physicians, residents, and non-physician practitioners (i.e., physician assistants and nurse practitioners) who provide medical care to adolescents. The questionnaire was sent to these providers' academic email addresses between July 15 and August 15, 2022. All participants who completed the questionnaire were included in the analyses.

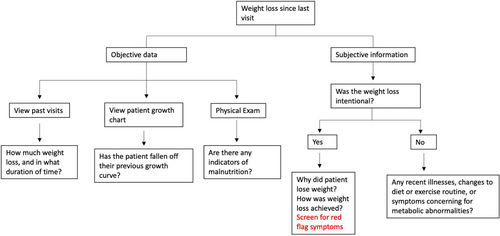

The questionnaire (Appendix 1) was developed by the study's three authors, including an adolescent medicine physician (J. S.) and clinical psychologist (J. E.) with expertise in eating disorders. Questions assessed familiarity, knowledge, and current practices regarding the detection and management of patients with suspected AN and atypical AN. Participants responded to the same questions about AN and atypical AN (e.g., “How familiar are you with a diagnosis of [AN/atypical AN]?”) in a counterbalanced order. The questionnaire included one continuous item assessing familiarity with AN and atypical AN on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (“very familiar”) to 5 (“not very familiar”), and several categorical items assessing knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward adolescents with AN versus atypical AN (items are included in Appendix 1). At the conclusion of the survey, participants were given the opportunity to view an atypical AN resource that discussed its increasing prevalence, introduced a diagnostic algorithm, and reviewed its “red flag” symptoms (Appendix 2). The Human Subjects Protections Office at the Penn State University determined that this study met criteria for IRB exemption.

A within-subjects t-test analyzed differences on the continuous item assessing familiarity with AN versus atypical AN. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) investigated the degree to which familiarity with AN versus atypical AN differed according to type of provider (General Pediatrics vs. Family Medicine), years in medical practice (less than 5 years vs. 5 or more years), and gender (female vs. male). Related-samples homogeneity tests analyzed differences on questions with multiple categorical responses. Related-samples McNemar tests compared the proportion of participants who endorsed each practice (e.g., “Refer the patient for psychotherapy”) for adolescents with AN versus atypical AN. A chi-square goodness of fit test evaluated whether a significant majority of participants endorsed interest in receiving resources to learn more about atypical AN.

According to G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., 2007), using standard effect size estimates (Cohen, 1992) and an alpha level of 0.05, our total sample size of 67 participants provides >99%, 98%, and 36% power to detect large, medium, and small effects, respectively, when conducting within-subjects t-tests. When conducting 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA, we have 96%, 64%, and 15% power to detect large, medium, and small between-group effects, respectively, and >99%, 98%, and 36% power to detect large, medium, and small interaction effects, respectively. When conducting chi-square tests with one degree of freedom, we have 98%, 69%, and 13% power to detect large, medium, and small effects, respectively.

We hypothesized that participants would be significantly less familiar with atypical AN, have less experience with atypical AN, would be less likely to recognize atypical AN, and be less likely to refer adolescents with atypical AN for specialized care compared to those with AN. We also hypothesized that pediatric clinicians (compared to family medicine clinicians, who generally treat fewer adolescent patients as a proportion of their total patients), those with 5 or more years of practice (compared to those with less than 5 years of practice, who may have had less exposure to patients with atypical AN), and female clinicians (compared to males, who tend to be less likely to recognize the severity of eating disorders [Brelet et al., 2021]) would report significantly greater familiarity with both atypical AN and AN overall, and a smaller gap in familiarity between atypical AN and AN.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

A total of 67 participants (18% of recruitment pool) started the questionnaire, and 62 (92.5% of participants) completed the questionnaire. Only those who completed the questionnaire were included in our analyses. As noted in Table 1, over half of our sample was female and White. The most common providers included Family Medicine attending physicians (34.3%), pediatric resident physicians (22.4%), and General Pediatrics attending physicians (20.9%). Slightly under half of participants (45.5%) have been in medical practice for less than 5 years.

| Variable | Number of participants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Provider type | ||

| General pediatrics attending physician | 14 | 20.9% |

| General pediatrics non-physician practitioner | 2 | 3.0% |

| Pediatric resident physician | 15 | 22.4% |

| Family medicine attending physician | 23 | 34.3% |

| Family medicine non-physician practitioner | 5 | 7.5% |

| Family medicine resident physician | 6 | 9.0% |

| Medicine/pediatrics resident | 2 | 3.0% |

| Years in medical practice | ||

| <5 | 30 | 45.5% |

| 5–10 | 11 | 16.7% |

| 11–20 | 10 | 15.2% |

| >20 | 15 | 22.7% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 37 | 55.2% |

| Male | 26 | 38.8% |

| Non-binary | 1 | 1.5% |

| Other gender | 0 | 0.0% |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 4.5% |

| Race | ||

| White | 54 | 80.6% |

| Black or African American | 0 | 0.0% |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 0 | 0.0% |

| Asian | 8 | 11.9% |

| Native Hawaiian | 0 | 0.0% |

| Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.0% |

| Other | 1 | 1.5% |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 | 6.0% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1 | 1.5% |

| Non-Hispanic | 61 | 91.0% |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 7.5% |

3.2 Familiarity with atypical AN and AN

On the continuous item, participants reported that they were significantly less familiar with atypical AN (M = 3.39, SD = 1.42) than AN (M = 2.33, SD = 1.24), t(50) = 4.99, p < .001, d = 1.51.

Consistent with our hypotheses, General Pediatrics providers reported more familiarity with both atypical AN (M = 3.09) and AN (M = 1.86) than Family Medicine providers (M = 3.71 and M = 2.75, respectively) F = 6.81, p = .012, ɳp2 = .12. There was no significant provider × familiarity interaction, F = .362, p = .550, suggesting that Family Medicine and General Pediatrics providers experienced a similar gap in familiarity between atypical AN and AN.

In contrast to hypotheses, providers with 5 or more years in medical practice reported a significantly larger gap in familiarity between atypical AN (M = 3.81) and AN (M = 2.19) than those with less than 5 years in practice (M = 2.92 for atypical AN; M = 2.50 for AN), resulting in a significant years in practice × familiarity interaction, F = 9.53, p = .003, ɳp2 = .16.

We did not find significant differences between female and male clinicians' reported familiarity with atypical AN and AN, F = .559, p = .458, or a gender × familiarity interaction, F = 1.538, p = .221.

3.3 Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward AN and atypical AN

Results from marginal homogeneity and McNemar tests analyzing responses to categorical items are reported in Table 2. As hypothesized, participants reported significantly greater uncertainty about the prevalence of atypical AN, and uncertainty about the impact of COVID-19 on rates of atypical AN, relative to AN. Participants were also significantly less likely to diagnose a patient with atypical AN, less comfortable identifying atypical AN, and less likely to correctly diagnose a sample vignette with atypical AN. Additionally, participants were significantly less likely to recommend that adolescents with atypical AN, relative to those with AN, schedule a follow-up appointment before their next annual medical visit (45.2% vs. 59.7%), less likely to refer adolescents with atypical AN than AN to an eating disorder specialist (58.1% vs. 77.4%), and more likely to report that they do not have a current approach to treating adolescents with atypical AN compared to those with AN (27.4% vs. 6.5%). A significant majority of participants (72.6%) expressed interest in receiving more resources to learn about atypical AN, χ2(1) = 12.65, p < .001.

| Item | AN percentages | AAN percentages | Q (r) | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated prevalence | 66*** (.32) | <.001 | |||

| Most (more than half) | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||

| Some (less than half) | 67.7% | 45.2% | |||

| None | 21.0% | 19.4% | |||

| Not sure | 8.1% | 33.9% | |||

| Does not apply to me | 3.2% | 1.6% | |||

| Frequency of diagnosis | 79*** (.34) | <.001 | |||

| Often | 1.6% | 1.6% | |||

| Sometimes | 24.6% | 16.4% | |||

| Rarely | 41.0% | 19.7% | |||

| Never | 26.2% | 55.7% | |||

| Does not apply to me | 6.6% | 6.6% | |||

| COVID-19 impact on prevalence | 20* (.18) | .049 | |||

| Increased | 49.2% | 41.0% | |||

| Decreased | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||

| No change | 9.8% | 8.2% | |||

| I don't know | 41.0% | 50.8% | |||

| Comfort identifying | 83*** (.50) | <.001 | |||

| All of the time | 11.3% | 3.2% | |||

| Most of the time | 53.2% | 16.1% | |||

| Some of the time | 30.6% | 45.2% | |||

| None of the time | 1.6% | 9.7% | |||

| Never heard of disorder | 3.2% | 25.8% | |||

| Diagnosing vignette | 26*** (.37) | <.001 | |||

| Correct diagnosis | 69.4% | 41.9% | |||

| Incorrect diagnosis | 24.2% | 40.3% | |||

| Not sure of diagnosis | 6.5% | 17.7% | |||

| Current approaches | |||||

| Counsel with annual follow-up | 4.8% | 4.8% | 0.00 | 1.000 | |

| Counsel with sooner follow-up | 59.7% | 45.2% | 4.27* | .039 | |

| Refer to dietitian | 40.3% | 30.6% | 2.50 | .114 | |

| Refer to therapy | 45.2% | 35.5% | 2.50 | .114 | |

| Refer to eating disorder specialist | 77.4% | 58.1% | 7.56** | .004 | |

| No current approach | 6.5% | 27.4% | 11.08*** | <.001 |

- Note: AN, anorexia nervosa; AAN, atypical anorexia nervosa; Q, marginal homogeneity test statistic; r, effect size estimate; χ2, McNemar test statistic.

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01;

- *** p < .001.

4 DISCUSSION

Our sample of Pediatric and Family Medicine clinicians appear to be less familiar with atypical AN compared to AN, despite evidence that atypical AN may be more prevalent than AN (Harrop et al., 2021). Over half (55.7%) of surveyed clinicians indicated that they have never diagnosed a patient with atypical AN, compared to approximately one-fourth (26.2%) who have never diagnosed a patient with AN. Furthermore, when asked about the prevalence of atypical AN in their practice, about one-third (33.9%) of participants indicated they were unsure or had not considered the diagnosis, compared to only 8.1% for AN. This reduced familiarity with atypical AN may be related to a lower likelihood of having a current approach to responding to adolescents with suspected atypical AN and being less likely to refer adolescents with possible atypical AN to an eating disorder specialist. This gap in provider knowledge regarding atypical AN may be attributed to the diagnostic ambiguity associated with atypical AN, lack of exposure to atypical AN, or inadequate educational opportunities to advance knowledge about atypical AN and eating disorders more broadly (Harrop et al., 2021).

Consistent with our hypotheses, General Pediatrics clinicians reported more familiarity with atypical AN and AN relative to Family Medicine providers. This familiarity may be due to the larger proportion of adolescents cared for in Pediatrics relative to the total ages of full patient panels in Family Medicine. Additionally, more inpatient eating disorder adolescents are cared for by the Pediatrics team. Thus, Pediatrics clinicians may have more exposure to patients with eating disorders.

Providers with 5 or more years of medical practice reported a larger gap in familiarity between atypical AN and AN than providers with less than 5 years of medical practice. Given the increasing prevalence (Sawyer et al., 2016) and awareness (Hartman-Munick et al., 2022) of atypical AN in recent years, it may be the case that newer clinicians have also been seeing increasing numbers of total eating disorder patients in their training, which could increase their ability to recognize and treat atypical AN earlier than those with less exposure to patients with eating disorders. Furthermore, atypical AN was only recognized as a new diagnosis in 2013, and 37.9% of our study sample had been in practice for greater than 10 years (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). If future research confirms that clinicians farther out of subspecialty training are indeed less familiar with atypical AN than newer clinicians, then it may be particularly beneficial to target these clinicians with efforts to increase provider knowledge about atypical AN.

At the conclusion of the survey, 72.6% of clinicians indicated interest in learning more about diagnosing atypical AN and were provided with a resource that included an algorithm for atypical AN detection using subjective and objective information and “red flag” symptoms. Individuals with AN attend more primary care appointments in the 5 years prior to receiving their diagnosis than the average patient, highlighting the opportunity for early detection and intervention due to these clinicians' unique, longitudinal relationships with patients (Higgins & Cahn, 2018). The standard assessment of weight, height, BMI, pubertal delay, and oligomenorrhoea likely aids in the identification of AN, but may fail to detect many adolescents with atypical AN. Likewise, current eating disorder screening tools such as the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (EDS-PC), Screen for Disordered Eating, and the SCOFF questionnaire, were designed to assess for AN, not atypical AN, and may fail to detect those with atypical AN (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2022). Developing screening tools that better identify atypical AN and training clinicians to better recognize the signs of atypical AN have the potential to reduce the number of adolescents with atypical AN who reach medical instability.

This study had a number of limitations. First, our study had a small sample size, and a low response rate of 18%. This low response rate may be related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a substantial impact on research and data collection across studies more broadly, including an increase in survey fatigue and reduced response rates (de Koning et al., 2021). Additionally, the email overload often experienced by healthcare providers has been shown to contribute to burnout (Armstrong, 2017). Interestingly, physicians have been found to be more responsive to mail surveys; future research conducted involving medical professionals may consider mail surveys, a multimode approach, and providing clinicians with multiple reminder notifications to complete the questionnaire (Menon & Muraleedharan, 2020). Our low response rate limits the generalizability of our findings, as the small proportion of providers who participated in this study may substantially differ from the larger pool of Pediatric and Family Medicine clinicians. In general, our sample size provided sufficient power to detect medium to large effects, but not small effects. Thus, any null results could be due to inadequate power, rather than a lack of an effect.

This study focused on Pediatric and Family Medicine clinicians, rather than a wider range of medical providers. Future research should explore the attitudes about atypical AN and AN among other medical specialties, as well as other types of providers who may be likely to interact with adolescents with eating disorders (e.g., dietitians, therapists), to get a better understanding of clinicians' knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Our study recruited participants from one health system with a predominantly White sample of clinicians, and may not generalize to more racially, ethnically, or geographically diverse populations. Furthermore, this study focused on clinicians' knowledge about the diagnostic labels of “atypical AN” and “AN.” Thus, lack of familiarity with the term “atypical AN” does not necessarily mean lack of familiarity with the symptoms of atypical AN. Instead of evaluating clinicians' attitudes about “atypical AN,” future research might instead assess responses to a vignette of someone with symptoms of atypical AN. However, without established guidelines for management of atypical AN in a Family Medicine or Pediatric setting, practice patterns will remain variable.

This study provides preliminary evidence that Pediatric and Family Medicine clinicians are less likely to identify adolescents with atypical AN relative to those with AN. If confirmed by future research, this would place adolescents with atypical AN at heightened risk for continued restrictive eating behaviors, malnutrition, detrimental health consequences, and persistent psychological challenges. Further research consisting of a larger, more diverse sample size should evaluate methods to increase providers' knowledge about atypical AN, with the aim of improving the identification of adolescents with atypical AN and preventing these individuals from experiencing the detrimental long-term health outcomes associated with eating disorders.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kelly Kons: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Jamal Essayli: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Jennifer Shook: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1 TR002014.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was given IRB exemption by the institutional review board at The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine.

APPENDIX 1: ATYPICAL ANOREXIA NERVOSA SURVEY SENT TO 364 PENN STATE HEALTH PEDIATRIC AND FAMILY MEDICINE ATTENDING PHYSICIANS, RESIDENTS, AND NON-PHYSICIAN PRACTITIONERS (I.E., PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS AND NURSE PRACTITIONERS) WHO PROVIDE MEDICAL CARE TO ADOLESCENTS.

- How familiar are you with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa? (Likert scale: 1 = very familiar, 5 = not at all familiar)

-

Which statement best reflects the prevalence of anorexia nervosa in your current adolescent patient population?

- I believe most (more than half) of my patients have anorexia nervosa

- I believe some of my adolescent patients (less than half) have anorexia nervosa

- To my knowledge, none of my adolescent patients have anorexia nervosa

- I'm not sure—I've never really considered anorexia nervosa as a diagnosis for my adolescent patients

- This question does not apply to me

-

How often do you diagnose patients with anorexia nervosa in your practice?

- Often (once a month or more times in the past year)

- Sometimes (several times in the past year)

- Rarely (once in the past year)

- Never

- This question does not apply to me

-

How do you think the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the prevalence of anorexia nervosa in the adolescent population?

- Increased

- Decreased

- No change

- I don't know

-

How comfortable do you feel identifying anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient?

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient all of the time.

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient most of the time.

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient some of the time.

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient none of the time.

- I have never heard of anorexia nervosa.

-

Which of the following patients would you be most likely to diagnose with anorexia nervosa?

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.) and lost from 68 kg (~150 lb) to 54 kg (~120 lb) by purposely restricting calories due to poor body image.

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.) and lost from 54 kg (~120 lb) to 43 kg (~95 lb) by restricting food intake due to poor body image.

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.) and lost from 54 kg (~120 lb) to 43 kg (~95 lb) by restricting food intake due to a prior choking episode that resulted in fears about eating.

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.), has weight fluctuations between 54 kg (~120 lb) and 68 kg (~150 lb), and engages frequently in binging and purging episodes due to poor body image.

- I'm not sure

-

Which statement best describes your current approach to an adolescent patient with suspected anorexia nervosa? (select all that apply)

- Counsel the patient on the health risks associated with weight loss and malnutrition and then follow up at next annual visit

- Counsel the patient on the health risks associated with weight loss and malnutrition and then follow up sooner than next annual visit

- Refer the patient to a registered dietitian

- Refer the patient for psychotherapy

- Refer the patient to an adolescent medicine provider who specializes in eating disorders

- I don't have a current approach to adolescent patients with suspected anorexia nervosa

- How familiar are you with a diagnosis of atypical anorexia nervosa? (Likert scale: 1 = very familiar, 5 = not at all familiar)

-

Which statement best reflects the prevalence of atypical anorexia nervosa in your current adolescent patient population?

- I believe most (more than half) of my patients have atypical anorexia nervosa

- I believe some of my adolescent patients (less than half) have atypical anorexia nervosa

- To my knowledge, none of my adolescent patients have atypical anorexia nervosa

- I'm not sure—I've never really considered atypical anorexia nervosa as a diagnosis for my adolescent patients

-

How often do you diagnose patients with atypical anorexia nervosa in your practice?

- Often (once a month or more times in the past year)

- Sometimes (several times in the past year)

- Rarely (once in the past year)

- Never

-

How do you think the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the prevalence of atypical anorexia nervosa in the adolescent population?

- Increased

- Decreased

- No change

- I don't know

-

How comfortable do you feel identifying atypical anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient?

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify atypical anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient all of the time.

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify atypical anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient most of the time.

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify atypical anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient some of the time.

- I feel that I would be able to appropriately identify atypical anorexia nervosa in an adolescent patient none of the time.

- I have never heard of atypical anorexia nervosa.

-

Which of the following patients would you be most likely to diagnose with atypical anorexia nervosa?

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.) and lost from 68 kg (~150 lb) to 54 kg (~120 lb) by purposely restricting calories due to poor body image.

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.) and lost from 54 kg (~120 lb) to 43 kg (~95 lb) by restricting food intake due to poor body image.

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.) and lost from 54 kg (~120 lb) to 43 kg (~95 lb) by restricting food intake due to a prior choking episode that resulted in fears about eating.

- A 15 year-old girl who is 160 cm (63 in.), has weight fluctuations between 54 kg (~120 lb) and 68 kg (~150 lb), and engages frequently in binging and purging episodes due to poor body image.

- I'm not sure.

-

Which statement best describes your current approach to an adolescent patient with suspected atypical anorexia nervosa? (select all that apply)

- Counsel the patient on the health risks associated with weight loss and malnutrition and then follow-up at next annual visit

- Counsel the patient on the health risks associated with weight loss and malnutrition and then follow-up sooner than next annual visit

- Refer the patient to a registered dietitian

- Refer the patient for psychotherapy

- Refer the patient to an adolescent medicine provider who specializes in eating disorders

- I don't have a current approach to adolescent patients with suspected atypical anorexia nervosa

-

Are you interested in receiving more resources to learn about atypical anorexia in adolescent patients?

- Yes

- No

APPENDIX 2: ATYPICAL ANOREXIA NERVOSA RESOURCE.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN) is diagnosed when patients meet criteria for anorexia nervosa (AN) and have lost significant weight but are within or above the normal body mass index range. Research has shown that while AAN is more prevalent than AN in communities, fewer AAN patients are being referred to appropriate adolescent medicine providers or psychiatrists for eating disorders (Harrop et al., 2021). Additionally, studies published by the American Academy of Pediatrics have shown that the psychological burden of the eating disorder may be more severe in patients with AAN compared to AN (Garber et al., 2019). Adolescents with AAN who have experienced a greater amount, rate, or duration of weight loss have significantly worse medical and nutritional status, independent of weight at hospital admission (Garber et al., 2019).

| Subjective information | Red flags | |

|---|---|---|

| Diet | Typical content of meals/day and where/when/with whom | Skipping meals, poor food intake, decreased appetite, anxiety surrounding meals |

| Feelings toward current diet and body image | ||

| Recent change in diet | Distress when diet is brought up, fear of weight gain, avoidance of fatty foods, carbohydrates, or other foods they consider “junk food” | |

| Appetite | ||

| Has anybody voiced concern regarding your eating habits? | Body dysmorphia or significant body dissatisfaction | |

| Exercise | Current level of activity | Overexercising, obsessing, distress related to physical fitness/shape |

| Exercise activities | ||

| Has anybody mentioned anything to you about your current level of physical activity? | Time spent on exercise interfering with ability to do other social or normal activities | |

| Social History | Drug/alcohol use | Worsening academic performance, social withdrawal, obsession with social media |

| Peer pressure | ||

| Social support | ||

| Social stressors | ||

| Social media | ||

| Academic performance | ||

| Mental Health | Sad/anxious thoughts | Notable increase in sad and/or anxious thoughts and emotions |

| Menstruation | Age at menarche | Amenorrhea, change in regularity |

| Consistency/pattern of periods |

Any positive findings warrant further discussion and any red flag symptoms emphasize the need for short interval follow up and/or referral to an adolescent medicine provider, eating disorder specialist, or psychiatrist. Furthermore, nutritional status can be further explored through basic labs.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.