Difficult-to-Treat Epilepsy With Developmental Implications

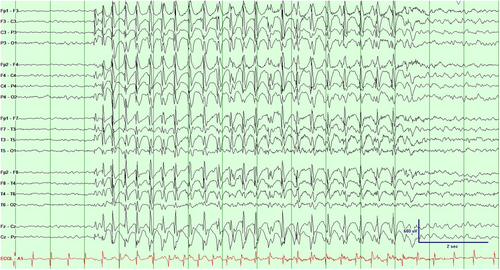

This 5-year-old girl presented with approximately 1 year of recurrent episodes of staring with rhythmic eye movements and upper extremity twitching. Development and cognition were normal. Electroencephalogram (EEG) captured typical events of behavioral arrest with staring associated with rhythmic upper body myoclonic jerks time-locked to generalized spike-wave discharges (Video 1/Figure 1). Photic stimulation induced events. Magnetic resonance imaging was normal. An epilepsy gene panel revealed a variant of unknown significance in ADAR/TREX1. Initial treatment with valproic acid (VPA) was unsuccessful, but adding clobazam resolved her seizures. Attempted simplification to monotherapy clobazam was unsuccessful, but she remained seizure-free when combination VPA and clobazam therapy was reintroduced.

Epilepsy with myoclonic absences (EMA) is an epilepsy syndrome characterized by absence seizures accompanied by myoclonic jerks and tonic abduction in the arms often appearing as a ratcheting movement [1]. The condition typically begins in early childhood and can persist into adulthood [2]. Cognitive and developmental impairments may arise from the interplay between the underlying epileptic condition and the effects of frequent seizures [3]. VPA is generally the first-line treatment, often combined with other antiepileptic drugs such as ethosuximide, benzodiazepines, or levetiracetam [1, 4]. However, age, metabolic conditions, and sex may impact first-line medication choice. Zonisamide, levetricetam, clobazam, and several others can be considered as second line or if VPA is not recommended [1, 2]. Primary sodium channel blockers, such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin, should be avoided to prevent exacerbating seizures [5]. Early diagnosis and treatment is crucial for better outcomes, as delayed therapy and the presence of generalized tonic-clonic seizures may indicate a poorer prognosis [2]. Proper medication management of EMA requires consideration of potential side effects and comorbidities.

Author Contributions

Samuel Kamoroff: conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, data curation. Harry Abram: writing – review and editing, supervision. Fernando Galan: writing – review and editing, visualization, supervision.

Consent

Parental consent was obtained due to the patient being a minor with identifiable physical features included in the video.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.