The highly sensitized, high MELD, simultaneous liver-kidney or status 1A heart-liver transplant candidate

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abbreviations

-

- AMR

-

- antibody-mediated rejection

-

- DSA

-

- donor-specific human leukocyte antigen antibody

-

- IHT

-

- isolated heart transplant

-

- KTA

-

- kidney transplant

-

- MFI

-

- mean fluorescence intensity

-

- SHLT

-

- simultaneous heart-liver transplantation

-

- SLK

-

- simultaneous liver-kidney

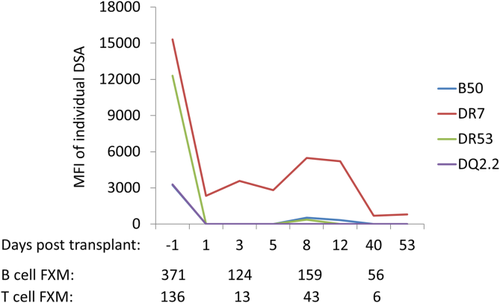

Detrimental effects of donor-specific human leukocyte antigen antibodies (DSAs) on kidney and heart allografts are well recognized, and antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) of these organs is a feared complication in highly sensitized recipients. The pattern of the alloimmune injury instigated by DSA in kidney and heart allografts is similar and involves endothelial cell injury, activation, and microvascular inflammation.1 Although much more resistant than other solid-organ allografts, DSA-mediated injury can also occur after liver transplantation. Because of the inherent ability of the liver to reduce the level of circulating DSA, as well as its unique regenerative capacity after a mild injury, most sensitized liver transplant recipients do not incur DSA-mediated graft injury (Fig. 1). In all, AMR of the liver is estimated to occur in less than 1% of all liver transplants and in about 5% of all sensitized liver recipients.2

Whereas approximately 20% of the potential recipients on the liver transplant waiting list are sensitized, this ratio is higher among those waiting for multiorgan transplants (e.g., liver-kidney or liver-heart), due mainly to increased blood transfusion requirement of the latter group. An obvious question then is whether hearts or kidneys that are transplanted simultaneously with livers to the highly sensitized patients will succumb to AMR. Given the increasing number of multiorgan transplants, two recent articles3, 4 studied the outcomes of such transplants to answer this question.

In the first study,3 we investigated the incidence of immune-mediated injury in a cohort of 68 simultaneous liver-kidney (SLK) recipients. Fourteen of these recipients were highly sensitized. These patients were then compared with 28 age-, sex-, race-, and sensitization status–matched solitary kidney transplant (KTA) recipients maintained with the same immunosuppression protocol. Routine protocol kidney biopsies that were obtained postoperatively at 4 months and 1, 2, and 5 years were examined. During a 6-year follow-up, no kidney allograft was lost to acute or chronic AMR in the SLK group, whereas three graft losses in the KTA were due to chronic DSA-mediated glomerulopathy. The overall incidence rates of acute AMR (7.1% in SLK versus 46.4% in KTA) and chronic glomerulopathy (0% in SLK versus 53.6% in KTA) were both markedly lower in SLK patients. These histological differences translated into a 44% decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate among the KTA recipients over the 5-year period, whereas the estimated glomerular filtration rate in SLK patients was preserved. In these highly sensitized recipients, the cumulative 5-year incidence rate of T cell–mediated rejection was also higher in KTA (30.6% versus 7.1% in SLK).

In the second study, Wong et al.4 reported the outcomes and incidence of immune-mediated injury after simultaneous heart-liver transplantation (SHLT). This analysis included 22 SHLT patients, and the comparison was done with 223 isolated heart transplant (IHT) recipients of the same era. This study's strength lies in the fact that 3912 protocol and indication-specific heart allograft biopsies were reviewed. Of the SHLT and IHT recipients, 23% and 8%, respectively, were highly sensitized. Some, but not all, in each group were treated with antibody-targeting therapies perioperatively. No patient underwent long-term antibody-targeting therapy. During a 5-year follow-up, no heart allografts were lost to AMR in SHLT, compared with four AMR-related graft losses in IHT. The cumulative incidence rate of AMR in the SHLT group was only 4.5%, as opposed to 14.8% among the IHT recipients. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy, a hallmark of endothelial cell injury and alloimmune activity, was observed less commonly and severely in SHLT patients. Multivariate analysis in both articles showed that the presence of a simultaneously transplanted liver reduced the risk for AMR and chronic DSA-mediated injury significantly in the heart and kidney allografts.

Although being relatively resistant to AMR itself, both of these studies3, 4 demonstrate that the liver allograft may also provide a protective effect to simultaneously transplanted organs from the same deceased donor. Utilizing more sensitive methods of DSA detection and additional clinical endpoints, the results confirm earlier observations.5 Several different mechanisms through which the liver resists DSA-mediated injury have been postulated, and these have been reviewed elsewhere.6 However, recent investigations show us that this resistance is not absolute and can be overcome in patients with very high levels of circulating DSA, liver allograft dysfunction, or noncompliance with the immunosuppression. In fact, among the SLK patients who were analyzed, persistent DSA after transplantation was observed only in those documented to be noncompliant or with recurrent liver disease.3

Given the wait-list mortality of high Model for End-Stage Liver Disease SLK and Status 1A heart-liver transplant candidates and the recent demonstration of the lower incidence of DSA-mediated injury in dual-organ transplant recipients, it appears that proceeding with transplantation whenever organs become available is warranted. A high level of awareness for possible AMR is required, and postoperative DSA monitoring is likely to help transplant clinicians in early detection and treatment before irreversible alloimmune injury occurs. Most importantly, compliance with immunosuppression appears to be crucial for the liver allograft to sustain its immunoprotective role over the long haul.