Autoimmune hepatitis: Diagnostic criteria and serological testing

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is based on a combination of clinical, biochemical, immunological, and histological features and the exclusion of other known causes of liver disease (e.g., hepatitis B, hepatitis C, Wilson's disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and drug-induced liver disease). Liver biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis and to evaluate the severity of liver damage1 (Fig. 1).

Three-quarters of patients are female. The presentation can be acute or insidious: 40% to 60% of patients present with chronic nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, and arthralgia. An acute presentation is more common in children and adolescents. Occasionally, AIH presents as fulminant hepatic failure. AIH may also be diagnosed after incidental findings of abnormal liver function tests. Because of the variability of its presenting features, AIH should be excluded for all patients with symptoms or signs of prolonged, relapsing, or severe liver disease so that treatment can be promptly initiated (Fig. 1).

In the absence of a single diagnostic test for AIH, the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) has devised a diagnostic system for comparative and research purposes that includes several positive and negative scores, the sum of which gives a value indicative of probable or definite AIH2, 3 (Table 1). A simplified IAIHG scoring system published more recently is better suited to clinical application4 (Table 2).

| Parameter | Feature | Scorea |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | +2 |

| ALP:AST (or ALT) ratio | >3 | −2 |

| 1.5-3 | 0 | |

| <1.5 | +2 | |

| Serum globulins or IgG (times above normal) | >2.0 | +3 |

| 1.5-2.0 | +2 | |

| 1.0–1.4 | +1 | |

| <1.0 | 0 | |

| ANA, SMA, or anti-LKM1 titer | >1:80 | +3 |

| 1:80 | +2 | |

| 1:40 | +1 | |

| <1:40 | 0 | |

| AMA | Positive | −4 |

| Viral markers of active infection | Positive | −3 |

| Negative | +3 | |

| Hepatotoxic drug history | Yes | −4 |

| No | +2 | |

| Average alcohol consumption | <25 g/day | +2 |

| >60 g/day | −2 | |

| Histological features | Interface hepatitis | +3 |

| Plasma cells | +1 | |

| Rosettes | +1 | |

| None of the above | −5 | |

| Biliary changesb | −3 | |

| Atypical changesc | −3 | |

| Immune diseases | Thyroiditis, colitis, and others | +2 |

| Human leukocyte antigen | DR3 or DR4 | +1 |

| Seropositivity for other autoantibodies | Anti-SLA/LP, actin, ASGPR, pANNA | +2 |

| Response to therapy | Remission | +2 |

| Relapse | +3 |

- This table has been adapted with permission from Journal of Hepatology.3 Autoantibody screening is frequently performed with automated techniques such as ELISAs and coated beads. These tests are reliable for SMA, anti-LKM1, anti-LC1, and anti-SLA antibodies, for which the target antigen is known, but not for ANAs, whose target in AIH has not been identified. The cutoff values for the automated tests vary between assays and laboratories.

- a A pretreatment score > 15 indicates definite AIH, and a pretreatment score of 10 to 15 indicates probable AIH. A posttreatment score > 17 indicates definite AIH, and a posttreatment score of 12 to 17 indicates probable AIH.

- b Including granulomatous cholangitis, concentric periductal fibrosis, ductopenia, marginal bile duct proliferation, and cholangiolitis.

- c Any other prominent feature suggesting a different etiology.

| Variable | Cutoff | Pointsa |

|---|---|---|

| ANA or SMA | ≥1:40 | 1 |

| ANA or SMA | ≥1:80 | 2b |

| or anti-LKM1 | ≥1:40 | |

| or SLA | Positive | |

| IgG | >Upper limit of normal | 1 |

| >1.10 times upper limit of normal | 2 | |

| Liver histology | Compatible with AIH | 1 |

| Typical of AIH | 2 | |

| Absence of viral hepatitis | Yes | 2 |

- This table has been adapted with permission from Hepatology.4 Autoantibody screening is frequently performed with automated techniques such as ELISAs and coated beads. These tests are reliable for SMA, anti-LKM1, anti-LC1, and anti-SLA antibodies, for which the target antigen is known, but not for ANAs, whose target in AIH has not been identified. The cutoff values for the automated tests vary between assays and laboratories.

- a A score ≥ 6 indicates probable AIH; a score ≥ 7 indicates definite AIH.

- b Additional points for all autoantibodies cannot exceed a maximum of 2.

Pathological Features

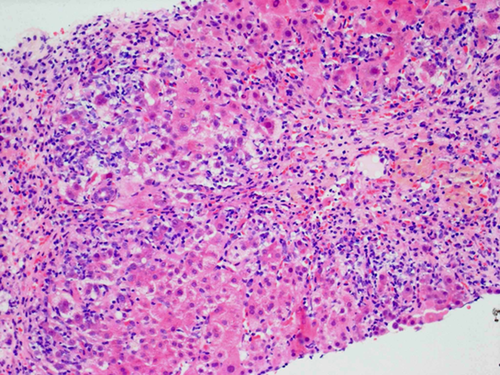

The typical histological feature of AIH is interface hepatitis, which is characterized by a dense inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells that crosses the limiting plate and invades the surrounding parenchyma (Fig. 2). Although plasma cells are characteristically abundant, their presence in low numbers does not exclude the diagnosis. When AIH presents acutely and during episodes of relapse, common histological findings are panlobular hepatitis with bridging necrosis and, if the disease takes a fulminant course, massive necrosis and multilobular collapse.

Although sampling variation may occur in needle biopsy specimens, particularly in cirrhotic livers, the severity of the histological appearance usually has prognostic value.

Autoantibodies

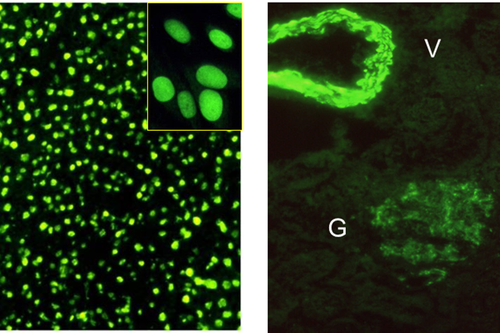

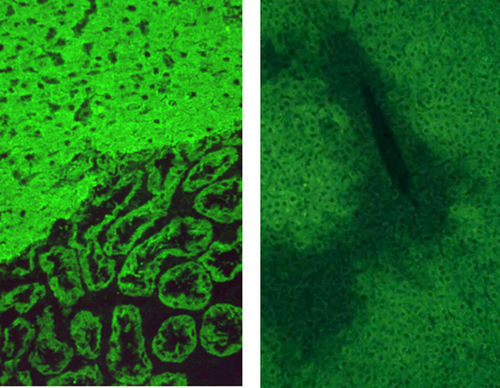

Key to the diagnosis of AIH is positivity for circulating autoantibodies,2-5 as emphasized by the guidelines to the diagnosis and management of AIH from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.1 The most reliable technique for their detection is indirect immunofluorescence (Figs. 3 and 4) on a rodent substrate, which not only assists in the diagnosis but also allows differentiation into two forms of AIH. Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) and smooth muscle antibodies (SMAs) characterize type 1 AIH, whereas anti–liver-kidney microsomal type 1 (anti-LKM1) and anti–liver cytosol type 1 (anti-LC1) antibodies define type 2 AIH. The two autoantibody profiles rarely occur simultaneously.

Because the interpretation of immunofluorescence patterns can be difficult, guidelines regarding the methodology and interpretation of liver autoimmune serology have been provided by the IAIHG.5

Autoantibodies are considered positive by immunofluorescence when they are present at a dilution ≥ 1:40 in adults, whereas in children, who are rarely positive for autoantibodies when they are healthy, positivity at a dilution ≥ 1:20 for ANAs and SMAs or ≥ 1:10 for anti-LKM1 is clinically significant.5 In both adults and children, autoantibodies may be present at a low titer or even be negative at disease onset and become detectable during follow-up.

In North America, autoantibody screening is frequently performed with automated techniques such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and coated beads. These tests can be used instead of immunofluorescence when the target antigen of the autoantibody is known: filamentous actin for SMAs, cytochrome P4502D6 for anti-LKM1, and formiminotransferase cyclodeaminase for anti-LC1. However, these automated tests have not been standardized: their cutoff values are assay/laboratory-specific, and their levels are not directly equivalent to immunofluorescence titers.

Because there are no ANA molecular targets specific for AIH and 30% of AIH patients who are positive for ANAs do not react with any of the known nuclear targets,6 immunofluorescence remains the gold standard for this autoantibody whether it is performed on rodent tissue or on human epithelial type 2 cells. A review by the American College of Rheumatology on the use of ELISAs and coated beads for testing for ANAs showed a worryingly high rate of false-negative results, and this led to the suggestion that hospitals/commercial laboratories using automated solid-phase assays for detecting ANAs should have to provide evidence that their assays have the same sensitivity and specificity as immunofluorescence.7

Other autoantibodies that are less commonly tested but have diagnostic importance and that should be requested if findings for standard autoantibodies are negative include anti–soluble liver antigen (anti-SLA) antibodies and anti–perinuclear neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (pANCAs).

Anti-SLA is highly specific for the diagnosis of AIH.6, 8 Its presence identifies patients with more severe disease and worse outcomes.9 Anti-SLA is not detectable by immunofluorescence. The cloning of its molecular target, Sep(O-phosphoserine) transfer RNA:Sec(selenocysteine) transfer RNA synthase,10 has led to the development of commercially available ELISAs.

Similarly to primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease, pANCAs are frequently detected in type 1 AIH. In contrast to type 1 AIH, pANCAs are virtually absent in type 2 AIH.5 The target of this autoantibody is unknown; hence, pANCAs can be detected only by immunofluorescence.

References

Abbreviations

-

- AIH

-

- autoimmune hepatitis

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- ALP

-

- alkaline phosphatase

-

- ANA

-

- anti-nuclear antibody

-

- ANCA

-

- anti–neutrophil cytoplasm antibody

-

- anti-LC1

-

- anti–liver cytosol type 1

-

- anti-LKM1

-

- anti–liver-kidney microsomal type 1

-

- anti-SLA

-

- anti–soluble liver antigen

-

- ASGPR

-

- asialoglycoprotein receptor

-

- AST

-

- aspartate aminotransferase

-

- ELISA

-

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

-

- IAIHG

-

- International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group

-

- IgG

-

- immunoglobulin G

-

- pANCA

-

- anti–perinuclear neutrophil cytoplasm antibody

-

- pANNA

-

- peripheral anti-nuclear neutrophil antibody

-

- SLA/LP

-

- soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas

-

- SMA

-

- smooth muscle antibody.