Interhospital transfers resulting in liver transplantation: Clinical, regulatory, and economic issues

Abstract

Content available: Audio Recording

Answer questions and earn CME

INTRODUCTION

Interhospital transfers resulting in liver transplantation are defined as hospital admissions resulting in liver transplantation in which the patient's admission originated at another hospital. This includes patients already on the transplant list and those who get evaluated, listed, and transplanted during that hospitalization. In addition, there undoubtedly exist many more transfers for the purpose of transplant evaluation, in which the transplant occurs during a later hospitalization or never occurs at all. Although transplant professionals play a major role in managing these transfers, almost no guidance exists in the literature on the relevant clinical, regulatory, and economic concerns.

LITERATURE FROM OTHER FIELDS

Multiple studies have identified that transfer patients are generally sicker than directly admitted patients, with numerous opportunities for medical errors during the transfer process.1, 2 Most studies come from the critical care literature, but publications exist in a wide variety of fields, such as cardiology, urology, and pediatrics.3-5 Six components to the transfer process have been identified: (1) initiation of transfer request; (2) management of transfer request and information exchange; (3) updates between transfer acceptance and patient transport; (4) transport; (5) patient admission and information availability; and (6) measurement, evaluation, and feedback.6 Patient safety risks exist at each of these stages related to delays, miscommunication, and resource limitations during the transfer process. For this reason several organizations such as the Academic Medical Center Patient Safety Organization have created working groups with consensus statements highlighting the importance of clear and frequent communication and standardized processes (https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/clinician-resources/guidelines-algorithms/2021/patient-safety-framework-for-inter-hospital-transfers-amc-pso).

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF TRANSFERS FOR LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

To describe the population of patients being transferred for liver transplantation in the United States, we queried the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from the years 2016–2018 to identify patients who underwent liver transplantation during that hospitalization, as determined by Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group 005 or 006. We divided this population into (1) patients transferred from another hospital versus (2) those admitted directly to the transplant center hospital and compared by demographics (age, sex, and race), length of stay (LOS), cost of stay, patient outcomes, payor type, and patient's population density of residency. Detailed methodology is available in the Supporting Information.

Among the 3653 patient admissions for liver transplant in the NIS database in 2016–2018, 717 (16.4%) were transferred from another hospital. Comparative statistics are shown in Table 1. Transferred patients tended to be slightly younger and more likely female. Greater percentages of transferred patients were more likely to hold either private insurance or Medicaid. No differences were seen in household income or rural/urban status. Transferred patients had nearly double the LOS and hospital charges and were more likely to be discharged (DC) to another inpatient facility or rehabilitation/skilled nursing facility. Interestingly, transferred patients were more likely to leave against medical advice (AMA). Lastly, patient mortality rate was slightly higher among transferred patients (2.97% vs. 2.15%; p < 0.001).

| Demographics | Transferred (n = 717) | Not transferred (n = 2936) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at admission (years) | 49.7 | 52.1 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.029 | ||

| Female | 59.15% | 36.52% | |

| Male | 40.85% | 63.48% | |

| Race | 0.86 | ||

| White | 63.88% | 66.55% | |

| Black | 8.35% | 9.24% | |

| Hispanic | 17.21% | 14.74% | |

| Asian & Pacific Islander | 5.11% | 4.24% | |

| Native American | 1.02% | 0.94% | |

| Other | 4.43% | 4.30% | |

| Total (n) | 587 | 3420 | |

| Mean LOS (days) | 30.6 | 16.9 | <0.001 |

| Mean total charges | $824,610.48 | $496,684.23 | <0.001 |

| Patient disposition | <0.001 | ||

| DC home | 34.90% | 48.41% | |

| DC to short-term hospital for inpatient care | 2.66% | 0.83% | |

| DC to other institution | 34.43% | 16.59% | |

| DC home health | 24.88% | 32.01% | |

| Left AMA | 0.16% | 0.00% | |

| Expired | 2.97% | 2.15% | |

| Total (n) | 639 | 2646 | |

| Payer type (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 22.71% | 26.41% | |

| Medicaid | 22.08% | 13.72% | |

| Private insurance | 47.16% | 41.50% | |

| Self-pay | 1.58% | 0.83% | |

| No charge | 0.00% | 0.23% | |

| Other | 6.47% | 17.31% | |

| Total (n) | 634 | 3010 | |

| Patient location | 0.5629 | ||

| Central | 32.76% | 30.91% | |

| Fringe | 25.24% | 28.67% | |

| Counties in metro 250,000–999,000 | 20.06% | 19.51% | |

| Counties in 50,000–249,999 | 7.52% | 7.97% | |

| Micropolitan counties | 7.68% | 7.20% | |

| Not metro or micropolitan | 6.74% | 5.74% | |

| Total (n) | 638 | 3624 | |

| Median household income | 0.387 | ||

| $0–$45,000 | 23.88% | 23.63% | |

| $45,001–$58,000 | 25.16% | 24.50% | |

| $58,001–$79,000 | 28.85% | 26.34% | |

| >$79,000 | 22.12% | 25.53% | |

| Total | 624 | 3576 |

- Note: Statistical significance p < 0.05. Variables defined: age, sex, race, LOS, total charges, disposition, payer type, patient location, and median household income. Disposition to other institutions, per Health Care Utilization Project (HCUP), include “Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF), Intermediate Care Facility (ICF), Another Type of Facility.” Payer types “Other,” per HCUP, include “Other insurances in Payer Type include Worker's Compensation, Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services (CHAMPUS), Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs (CHAMPVA), Title V, and other government programs.” Patient locations are urban-rural classification scheme of US counties and are unique in differentiating between central and fringe counties of large metropolitan areas.

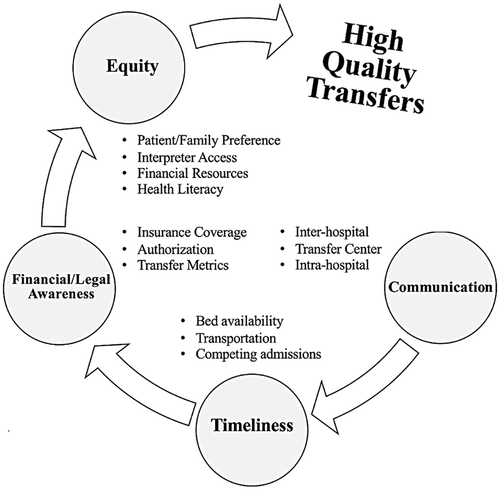

PROCESS CONCERNS AND GUIDANCE

- Referring and receiving hospitals should proactively develop a collaborative transfer plan to enhance communication between facilities and the transfer center. This can be achieved by defining clear goals, processes, delineation of responsibilities, and incentives for transfer center staff.

- Receiving hospitals should develop standardized procedures to prioritize patients being transferred for liver transplant evaluation. Because liver patients may have a narrow window of opportunity for a transplant, timely transfers may reduce adverse outcomes in this patient population.

- Transplant hepatologists at receiving hospitals should communicate daily with referring physicians and keep the transfer center and the admitting service updated on any changes in the patient's clinical status or transfer urgency. This will help expedite transfers as necessary and ensure a safe handoff between care teams once a patient is accepted for transfer. A daily meeting or update e-mail between the transplant team, transfer center staff, and the admitting service (if applicable) may facilitate this communication. In some cases, a preliminary psychosocial assessment (by the transplant social worker or psychologist) can also be done to clarify transplant candidacy before the patient is accepted for transfer to prevent futile transfers.

- Receiving hospitals should perform financial and legal analyses to determine the economic and legal impacts of interhospital transfers. Given the high cost and LOS for transfer patients and variable reimbursement in different regions of the country, each institution should perform its own analysis to guide their transfer policies.

- Receiving hospitals should acquire in-depth understanding of insurance authorization and reimbursement for interhospital transfers. This will assist with balancing expedient patient care with financial assurance for the hospital.

- Referring and receiving hospitals must implement transfer policies that promote equity in access to transfers to minimize disparities in care. Barriers to transplant can begin at the referring hospital and continue even after transfer. System-based efforts to integrate patient and family preference and address social determinants of health are paramount in improving the quality of transfers.

Several scenarios are particularly challenging. First, for patients with high Model for End-stage Liver Disease scores or those with acute liver failure, a rapid transfer can make the difference between life and death. In these situations, it is often helpful to escalate to hospital leadership. Second, the move toward transplanting selected patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis has caused a spike in transfer requests, and many of these patients will not be transplant candidates. To prevent a large volume of unnecessary transfers, some centers will have their transplant social workers perform a preliminary evaluation before determining whether to accept. Third, as mentioned earlier, the cohort of transferred patients who receive a liver transplant represents only the tip of the iceberg of patients transferred for advanced liver disease. Many patients are transferred for other higher level of care interventions, and many transfer requests are declined by the receiving center because of capacity or medical instability. Future studies should also include these populations.

In summary, interhospital transfers for transplantation are common and associated with worse outcomes than among patients who were not transferred. We provide some initial recommendations for what a high-quality transfer might look like. Future studies should include quantitative and qualitative analyses to identify determinants of high-quality transfers, including from the patient's perspective.

FUNDING INFORMATION

N.J.K. was supported by NIDDK Grant T32DK007742. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

J.A. consults for Gilead.