Safety and Efficacy of Two Ultrathin Biodegradable Polymer Sirolimus-Eluting Stents in Real-World Practice: Genoss DES Stents Versus Orsiro Stents From a Prospective Registry

ABSTRACT

Background

The Orsiro and Genoss DES stents are biodegradable polymer drug-eluting stents (DESs) with ultrathin struts.

Objective

To investigate the safety and efficacy of these two ultrathin DESs in real-world practice.

Methods

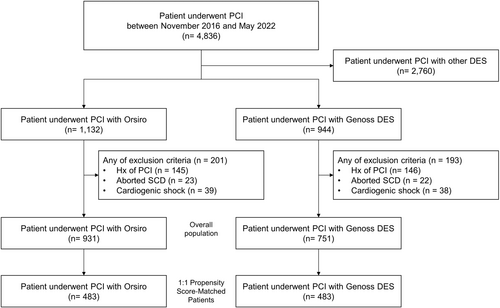

From a single-center prospective registry, we included 751 and 931 patients treated with the Genoss DES and Orsiro stents, respectively. After propensity score matching, we compared 483 patients in each group with respect to a device-oriented composite outcome (DOCO), which comprised cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization up to 2 follow-up years.

Results

After propensity score matching, there were no significant between-group differences in clinical and angiographic characteristics. During the median follow-up period of 730 days (interquartile range, 427–730 days), there was no significant between-group difference in the DOCO rate (3.1% in the Genoss DES group vs. 2.9% in the Orsiro group, log-rank p = 0.847).

Conclusions

This study demonstrated comparable safety and efficacy between the Orsiro and Genoss DES stents during a 2-year follow-up period in real-world practice. However, this result should be confirmed in a large randomized controlled trial.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02038127.

1 Introduction

Drug-eluting stents (DES) are considered a standard treatment for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [1]. Given the risk of very late stent thrombosis with DES due to delayed arterial healing related to hypersensitivity to durable polymers, biodegradable polymer DESs have been developed [2]. Although a biodegradable polymer DES with a thicker strut has an increased risk of stent thrombosis compared with durable polymer cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stents (EES), biodegradable polymer DES with an ultrathin strut involves a decreased rate of myocardial infarction (MI) and a trend towards reduced stent thrombosis compared with contemporary durable polymer DES [3-5].

The Orsiro stent (Biotronik AG, Bülach, Switzerland) is a biodegradable polymer DES with an ultrathin strut comprising a 60-μm cobalt-chromium L605 platform covered with an amorphous silicon carbide layer. It releases sirolimus from a biodegradable poly L-lactic acid (PLLA) polymer. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that the Orsiro stent is superior or non-inferior to the durable polymer EES and zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES) with respect to safety and efficacy in a broad spectrum of patients [6-12].

The Genoss DES stent (Genoss Company Limited, Suwon, South Korea) is another biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent with an ultrathin strut. This biodegradable coating comprises a proprietary blend of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) and PLLA. Compared with the Orsiro stent, the Genoss DES stent has a slightly thicker cobalt-chromium L605 platform (70 μm vs. 60 μm) but thinner polymer (3.0 μm vs. 7.4 μm). However, the polymer coatings of the Orsiro and Genoss DES stents are circumferential and abluminal, respectively. Accordingly, the Genoss DES stent has a lower total thickness (strut + polymer) than the Orsiro stent. In an interim analysis of a single-arm prospective registry, the Genoss DES stent showed excellent safety and efficacy in all-comer patients [13]. However, the Genoss DES stent was compared with the durable polymer platinum-chromium EES (Promus Element stent, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) in a small first-in-man trial [14].

This study aimed to compare the safety and efficacy of these two ultrathin DESs in real-world practice.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Population

From a prospective Gangwon PCI registry (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02038127), which enrolls patients undergoing PCI at three tertiary hospitals in Gangwon province, South Korea, we selected 4836 patients from a single center between November 2016 and May 2022. Among them, we selected 751 and 931 patients treated with the Genoss DES and Orsiro stents, respectively. The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (CR320095) and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki revised in 2013. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment in the registry.

2.2 Study Endpoints and Follow-Up

The primary endpoint was a device-oriented composite outcome (DOCO), which comprised cardiac death, MI not clearly attributable to a nontarget vessel, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization. The secondary endpoints included a patient-oriented composite outcome (POCO) comprising any death, MI, and revascularization; Academic Research Consortium-defined stent thrombosis; and each component of the primary and secondary endpoints. Details and definitions of the endpoints have been described elsewhere [15].

Clinical follow-ups were performed at 6, 12, and 24 months by office visits, medical record reviews, or telephone interviews. Data regarding the patients’ clinical status, interventions, and outcome events were recorded at every visit. Routine follow-up angiography was not permitted.

2.3 PCI and Medical Treatment

PCI was performed according to the standard technique. Decisions regarding the vascular access site; pre-dilatation or direct stenting; use of heparin or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors; image guidance PCI; use of pressure wire, which is a technique for bifurcation or chronic total occlusion lesion; and stent selection were at the operator's discretion. A staged procedure was allowed and was not considered as revascularization. The selection and duration of antiplatelet therapy were at the physician's discretion. A loading dose of aspirin (300 mg) and P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel [600 mg], prasugrel [60 mg], or ticagrelor [180 mg]) was administered to all patients ≤ 6 h before the procedure, unless the patient had been taking these medications or the procedure was an emergency situation. After the index PCI, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with a maintenance dose of aspirin (100 mg) and P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel [75 mg QD], prasugrel [10 mg QD], or ticagrelor [90 mg BID]) was encouraged for ≥ 12 months. Moreover, guideline-directed medical treatment with beta-blockers, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, and statins were encouraged.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables are presented as a number (percentages) and were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) and were compared using the independent sample t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Cumulative events of clinical outcomes were assessed using Kaplan–Meier estimates and compared using the log-rank test. All analyses were truncated at 24 months of follow-up owing to between-group differences in the follow-up duration. Analyses for all clinical endpoints were performed until the date of an endpoint event, loss to follow-up, or up to 24 months after the index procedure, whichever came first. Propensity scores were estimated by fitting a logistic regression model with the clinical, angiographic, and procedural variables presented in Tables 1 and 2. Nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.05 was used. To determine the balance in the established propensity score-matched sample, standardized mean differences were used for between-group comparisons of the means of the continuous and binary covariates. A standard difference of < 0.1 was considered indicative of negligible difference (Figure S1) [16]. Subgroup analyses of the primary endpoint were conducted based on age (< 65 years or ≥ 65 years), sex, diabetes mellitus, acute MI, stent diameter (> 2.5 mm vs. ≤ 2.5 mm), and length (< 38 mm vs. ≥ 38 mm). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) and SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| Variables | Orsiro n = 483 | Genoss DES n = 483 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 343 (71.0) | 350 (72.5) | 0.617 |

| Age, year | 66.7 ± 11.5 | 66.7 ± 11.0 | 0.964 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.0 ± 3.4 | 25.0 ± 3.2 | 0.981 |

| SBP, mmHg | 142 ± 24 | 141 ± 24 | 0.688 |

| DBP, mmHg | 83 ± 14 | 83 ± 15 | 0.555 |

| HR, BPM | 77 ± 15 | 76 ± 15 | 0.232 |

| Hypertension | 284 (58.8) | 272 (53.6) | 0.435 |

| Diabetes | 165 (34.2) | 159 (32.9) | 0.683 |

| Insulin-dependent | 12 (2.5) | 16 (3.3) | 0.443 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 92 (19.0) | 99 (20.5) | 0.572 |

| Dialysis dependent | 7 (1.4) | 8 (1.7) | 0.795 |

| Dyslipidemia | 161 (33.3) | 157 (32.5) | 0.784 |

| Prior CVA | 39 (8.1) | 41 (8.5) | 0.815 |

| Current or ex-smoker | 305 (63.1) | 313 (64.8) | 0.592 |

| Stable angina | 69 (14.3) | 70 (14.5) | 0.927 |

| Unstable angina | 125 (25.9) | 128 (26.5) | 0.826 |

| NSTEMI | 151 (31.3) | 141 (29.2) | 0.484 |

| STEMI | 86 (17.8) | 95 (19.7) | 0.458 |

| Primary PCI | 71 (14.7) | 79 (16.4) | 0.477 |

| Silent ischemia | 33 (6.8) | 33 (6.8) | > 0.999 |

| CAG diagnosis | 0.433 | ||

| 1-VD | 148 (30.6) | 155 (32.1) | |

| 2-VD | 157 (32.5) | 169 (35.0) | |

| 3-VD | 178 (36.9) | 159 (32.9) | |

| Treated lesion | |||

| LAD | 328 (67.9) | 313 (64.8) | 0.307 |

| LCX | 132 (27.3) | 133 (27.5) | 0.943 |

| RCA | 175 (36.2) | 175 (36.2) | > 0.999 |

| LM | 24 (5.0) | 23 (4.8) | 0.881 |

| Moderate to severe angulation | 7 (1.4) | 4 (0.8) | 0.363 |

| Moderate to severe calcification | 91 (18.8) | 82 (17.0) | 0.450 |

| SYNTAX score | 22.9 ± 14.8 | 21.9 ± 14.0 | 0.230 |

| Multi-vessel PCI | 179 (37.1) | 171 (35.4) | 0.592 |

| FFR guidance | 49 (10.1) | 18 (3.7) | < 0.001 |

| IVUS guidance | 298 (61.7) | 267 (55.3) | 0.043 |

| CTO PCI | 24 (5.0) | 19 (3.9) | 0.435 |

| Bifurcation PCI | 279 (57.8) | 278 (57.6) | 0.948 |

| with 2-stent strategy | 11 (2.3) | 12 (2.5) | 0.833 |

| Transradial access | 470 (97.3) | 463 (95.9) | |

| Implanted stent n | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.736 |

| Implanted stent length, mm | 46.6 ± 27.7 | 46.6 ± 30.0 | 0.990 |

| Implanted stent diameter, mm | 3.10 ± 0.39 | 3.09 ± 0.42 | 0.854 |

| Periprocedural complication | |||

| No reflow phenomenon | 26 (5.4) | 39 (8.1) | 0.095 |

| Side branch occlusion | 17 (3.5) | 21 (4.3) | 0.508 |

| Edge dissection | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.6) | 0.725 |

| Perforation | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | > 0.999 |

| Stent migration | 5 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0.062 |

| Discharge medication | |||

| Aspirin | 459 (95.0) | 465 (96.3) | 0.344 |

| Clopidogrel | 266 (55.1) | 258 (53.4) | 0.605 |

| Prasugrel or ticagrelor | 209 (43.3) | 221 (45.8) | 0.437 |

| Statin | 440 (91.1) | 437 (90.5) | 0.739 |

| Beta-blocker | 284 (58.8) | 275 (56.9) | 0.558 |

| ACEi or ARB | 290 (60.0) | 294 (60.9) | 0.792 |

- Note: Values are n (%) and mean ± SD.

- Abbreviations: ACEi, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, Angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CAG, coronary angiography; CTO, chronic total occlusion; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DES, drug-eluting stent; FFR, Fractional Flow Reserve; HR, heart rate; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LM, left main; NSTEMI, Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; SBP, systolic blood pressure; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SYNTAX, SYNergy between PCI with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery; VD, vessel disease.

| Orsiro n = 483 | Genoss DES n = 483 | Log rank p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up, days | 730 (391, 730) | 730 (497, 730) | |

| DAPT duration, days | 370 (291, 519) | 371 (321, 422) | 0.503 |

| In-hospital death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | n/a |

| Device-oriented composite outcomea | 14 (2.9) | 15 (3.1) | 0.847 |

| Cardiovascular death | 9 (1.9) | 7 (1.4) | 0.533 |

| Target vessel-related MI | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 0.921 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 5 (1.0) | 7 (1.4) | 0.697 |

| Patient-oriented composite outcome | 32 (6.6) | 36 (7.5) | 0.989 |

| Any death | 16 (3.3) | 11 (2.3) | 0.262 |

| Any MI | 9 (1.9) | 7 (1.4) | 0.492 |

| Any PCI | 14 (2.9) | 22 (4.6) | 0.284 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 9 (1.9) | 12 (2.5) | 0.665 |

| Stent thrombosis | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0.597 |

| Subacute definite | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Late definite | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Very late definite | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Subacute probable | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

- Note: Values are n (%) or median (interquartile range).

- Abbreviations: DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DES, drug-eluting stent; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

- a Primary endpoint.

3 Results

As shown in Figure 1, 931 and 751 patients in the Orsiro and Genoss DES groups, respectively, were compared as a crude population after excluding the patients with a prior history of PCI, aborted sudden cardiac death, or cardiogenic shock to reduce potential bias. Finally, 483 patients in either group were compared after propensity score matching.

3.1 Overall Population

Baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics in a crude population are presented in Supporting Information S1: Table 1. The mean age was 66.7 ± 11.4 years, with 71.1% of the patients being male. Approximately 57.4% of the patients had hypertension, 34.5% had diabetes, 20.6% had chronic kidney disease, and 62.2% were either current or ex-smokers.

Non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, multi-vessel disease, and multi-vessel PCI were more prevalent in the Orsiro group than in the Genoss DES group. Accordingly, the implanted stent number and length were significantly higher in the Orsiro group than in the Genoss DES group. The left anterior descending artery was the most commonly treated lesion in both groups, with a higher prevalence in the Orsiro group than in the Genoss DES group. However, left main artery disease was more prevalent in the Genoss DES group than in the Orsiro group. The rate of moderate-to-severe angulation of the treated lesions was similar between the two groups. However, the rate of moderate-to-severe calcification was more prevalent in the Orsiro group than in the Genoss DES group. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance for PCI were more prevalent in the Orsiro group than in the Genoss DES group. However, the occurrence of periprocedural complications, including the no-reflow phenomenon, side branch occlusion, edge dissection, perforation, and stent migration, was not different between the two groups.

Medication usage at discharge was different between the two groups (Supporting Information S1: Table 2). The Genoss DES group had a higher prescription rate of clopidogrel, while the Orsiro group had a higher prescription rate of potent P2Y12 inhibitors (Prasugrel or ticagrelor). Additionally, statins and beta-blockers were prescribed more frequently in the Orsiro group than in the Genoss DES group.

Despite the between-group differences in baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics, there were no between-group differences in the DOCO rate (4.3% vs. 5.1%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.57–1.38; log-rank p = 0.581) and POCO rate (6.5% vs. 8.7%; HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.73–1.40; log-rank p = 0.964) over a median follow-up period of 730 days (interquartile range, 427–730 days) (Supporting Information S1: Table 3 and Supporting Information S1: Figure 2). Other clinical outcomes did not significantly differ between the two groups.

3.2 Propensity Score-Matched Population

After propensity score matching, the two groups were well matched in baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics, except for a lower rate of physiology- and image-guided PCI in the Genoss DES group than in the Orsiro group. Furthermore, medication usage at discharge was well matched (Table 1).

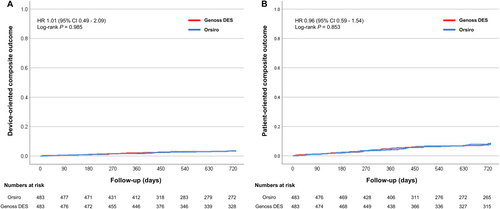

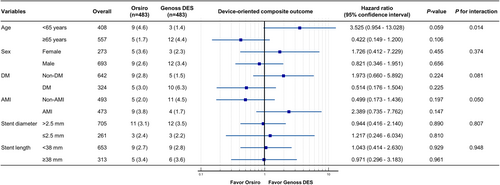

Clinical outcomes are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. During a median follow-up period of 730 days (interquartile range, 427–730 days), the DOCO rate (2.9% vs. 3.1%, HR 1.01; 95% CI, 0.49–2.09; log-rank p = 0.985) and POCO rate (6.6% vs. 7.5%, HR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.59–1.54; log-rank, p = 0.853) were similar between the two groups, with a similar duration of DAPT. Furthermore, other clinical outcomes were similar between the two groups. The rates of DOCO were consistent across the subgroups, except for those based on age (Figure 3).

4 Discussion

This study presents the first comparison between the ultrathin Genoss DES and ultrathin Orsiro stents in real-world practice over an extended follow-up period. The main finding was that the Genoss DES stent had similar safety and efficacy profiles at 24 follow-up months compared with the Orsiro stent after propensity score matching.

The Orsiro stent has been compared with the standard of care—a thin strut of either the durable polymer EES (Xience Prime/Xpedition stent, Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA) or ZES (Resolute Integrity/Onyx stent, Medtronic, Santa Rosa, CA, USA)—in several large RCTs [6-12]. In the first large, international, randomized non-inferiority BIOFLOW V trial, the Orsiro stent showed a significantly lower rate of target lesion failure (TLF) than the Xience stent (6.2% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.04), which was mainly attributed to the between-stent difference in target vessel MI (5% vs. 8%) at 12 months [9]. This finding was consistent at the 2-year follow-up of the BIOFLOW V trial [17]. However, these two stents showed a similar rate of TLF in the all-comer BIOSCIENCE trial (6.5% vs. 6.8%) [6]. In a subgroup analysis of the BIOSCIENCE trial, the Orsiro stent showed a lower rate of TLF than the Xience stent in 407 patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) (3.4% vs. 8.8%) [18]. The subsequent BIOSTEMI trial compared these two stents in patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI [11]. Bayesian analysis of the STEMI subgroup in the BIOSCIENCE trial confirmed that the Orsiro stent was superior to the Xience stent in terms of TLF (4% vs. 6%). The BIONYX trial compared the Orsiro stent with the novel single-wire designed ZES (Resolute Onyx stent) in an all-comer population [10]. Although increased definite or probable stent thrombosis was observed with the Orsiro stent (0.7% vs. 0.1%), both stents showed similar target vessel failure rates (4.7% vs. 4.5%, respectively) at 12 months. The three-arm BIO-RESORT trial compared the Orsiro stent with another biodegradable polymer platinum-chromium thinner strut (74 μm) EES (Synergy stent, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) and the Resolute Integrity stent [8]. At the 3 follow-up years, the Orsiro stent showed the lowest rate of TLF (7.0%, Orsiro group: 9.5%, Synergy group: 10.0%, Resolute Integrity group) [19].

The favorable outcomes of the Orsiro stent might be mainly attributed to its thinner strut and biodegradable polymer, regardless of the difference in drug and stent design. Although the Genoss DES stent has a slightly thicker strut than the Orsiro stent, the polymer is thinner and coated on the abluminal stent; accordingly, it has a lower total stent thickness. Therefore, considering the stent thickness, a favorable clinical outcome could be expected. In a small first-in-man trial, angiographic and clinical outcomes at 9 months were similar between the Genoss DES (n = 38) and Promus Element stents (n = 39) [14]. At 5 follow-up years, these two stents showed a similar rate of adverse clinical outcomes (5.3% in the Genoss DES stent vs. 12.8% in the Promus Element stent, p = 0.431) [20]. Given the small sample size, a prospective multicenter single arm Genoss DES registry study was subsequently conducted in South Korea. In an interim analysis of this registry, the Genoss DES stent showed excellent clinical outcomes (0.6% of DOCO, 3.9% of POCO, and 0.6% of definite or probable stent thrombosis) in 622 all-comer patients at 1 follow-up year [13]. In the final analysis of this registry, the Genoss DES stent showed consistently excellent clinical outcomes (1.8% for DOCO, 4.0% for POCO, and 0.4% for definite or probable stent thrombosis) among 1999 all-comer patients at the 1-year follow-up [21]. Given the lack of a comparator in the Genoss DES registry, the present study was conducted. Our findings demonstrated similar safety and efficacy of the Genoss and Orsiro stents in a real-world practice up to the 2-year follow-up period.

This study has several limitations. First, despite utilizing propensity score matching in our patient selection from the prospective registry, the potential for selection bias remains. Notably, the use of FFR and IVUS guidance was higher in the Orsiro group, likely reflecting operator preference. However, it is important to note that neither FFR nor IVUS guidance were significant predictors of the DOCO in this study. In addition, our subgroup analysis revealed an interaction for age in the DOCO (< 65 years vs. ≥ 65 years), which was not evident in the overall population. Second, the overall event rates observed were relatively low, even though this was a prospective registry trial based on real-world practice. This could be attributed to several reasons: (1) the exclusion of procedure-related MI from our analysis; (2) the use of potent ADP-receptor antagonists in approximately 50% of the patients; (3) the predominant use of radial access (over 90%); and (4) possible ethnic or genetic factors that may be associated with lower clinical event rates. These elements should be considered when interpreting the results of our study.

5 Conclusion

In a single-center prospective registry with use of the Genoss DES and Orsiro stents, both ultrathin DESs showed comparable safety and efficacy during the 2-year follow-up period. However, future studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are warranted to further validate these findings.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.