Cusp overlap method for self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Abstract

Background

Conduction disturbances and the need for permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation remains a common complication for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), particularly when self-expanding (SE) valves are used.

Aims

We compared in-hospital and 30-day rates of new PPM implantation between patients undergoing TAVR with SE valves using the conventional three-cusp coplanar implantation technique and the cusp-overlap technique.

Methods

We retrospectively compared patients without a pre-existing PPM who underwent a TAVR procedure with SE Evolut R or PRO valves using the cusp-overlap technique from July 2018 to September 2020 (n = 519) to patients who underwent TAVR using standard three-cusp technique from April 2016 to March 2017 (n = 128) in two high volume Canadian centers.

Results

There was no significant difference in baseline RBBB between the groups (10.4% vs. 13.2; p = 0.35). The rate of in-hospital new complete heart block (9.4% vs. 23.4%; p ≤ 0.001) and PPM implantation (8% vs. 21%; p ≤ 0.001) were significantly reduced when using the cusp-overlap technique. The incidence of new LBBB (30.4% vs. 29%; p = 0.73) was similar. At 30 days, the rates of new complete heart block (11% vs. 23%; p ≤ 0.001) and PPM implantation (10% vs. 21%, p ≤ 0.001) remained significantly lower in the cusp-overlap group, while the rate of new LBBB (35% vs. 30%; p = 0.73) was similar.

Conclusion

Cusp-overlap approach offers several potential technical advantages compared to standard three-cusp view, and may result in lower PPM rates in TAVR with SE Evolut valve.

1 INTRODUCTION

Conduction disturbances and the need for permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation remain a frequent limitation of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).1 This risk has historically been higher with self-expanding (SE) rather than balloon-expandable TAVR. In recent studies of TAVR in low surgical risk patients, the outcomes of TAVR were favorable in relation to SAVR, but the excess of pacemaker implantation with SE TAVR was noted2; the rate of new PPM was 17.4% with SE TAVR, 6.6% with balloon-expandable TAVR,3 and 4.1%–6.1% with SAVR.2, 3 However, implantation approach has emerged as an important determinant of the need for PPM, with higher TAVR device implantation associated with lower rates of PPM.4, 5

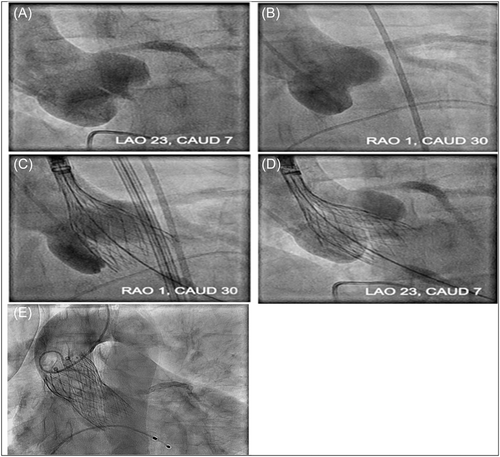

Identifying the optimal fluoroscopic projection of the aortic valve (AV) is important for successful TAVR, given the critical need to position and deploy the valve prosthesis accurately. This is best achieved by using a fluoroscopic view perpendicular to the native valve, called the “coplanar” view. Unlike balloon-expandable valves, the standard coplanar three-cusp view may not be ideal for deployment of the SE Evolut R/Pro (Medtronic) valve, as deployment requires minimization of the parallax of valve frame (Figure 1A). Removing this parallax typically requires caudal or left anterior oblique (LAO) angulation of the c-arm. This, in turn, results in a noncoplanar view, and instead one in which the right cusp is displaced superior. This results inadvertently in a deeper-than-appreciated implant, particularly under the right cusp.

The cusp overlap view isolates the noncoronary cusp (NCC) by overlapping the right coronary cusp (RCC) and left coronary cusp (LCC) and offers several advantages in SE valve deployment (Figure 1B). This view provides a good anatomical reference for deployment depth at the point of contact (NCC) as it maintains basal plane alignment of coronary cusps, elongates the outflow tract in a long axis view, reduces or eliminates parallax in the catheter marker band, and assists with depth visualization near the nonright commissure and membranous septum (MS) during deployment, thereby allowing for more accurate and higher valve implantation. In this study, we compare in-hospital and 30-day rates of new PPM between patients undergoing TAVR with the SE valves (Evolut R/Pro) using the conventional three-cusp coplanar implantation technique versus the cusp-overlap technique.

2 METHODS

In this retrospective study, patients who underwent a TAVR procedure using the cusp overlap technique with Evolut SE valve from July 2018 to September 2020 in two academic Canadian centers (Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and St Michael's Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada), were compared to patients who underwent TAVR using standard three-cusp technique from April 2016 to March 2017. We excluded patients from April 2017 to June 2018, to have a washout period when the sites were transitioning from a traditional three-cusp to the two-cusp overlap approach. Both hospitals have performed TAVR procedures since 2008–2009. The comparator period of 2016–2017 was chosen such that a contemporary cohort was used in comparison with the cusp-overlap period.

Research ethics approval was obtained from the research ethics board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and St Michael's Hospital. We included all patients who were discharged alive from the hospital following TAVR. Patients who died during TAVR procedure or had a PPM before the TAVR procedure were excluded. All patients underwent preoperative transthoracic echocardiography and multidetector computed tomography to evaluate aortic annulus dimensions, morphology, and calcification. Data were obtained from clinical records and 30-day clinical outcomes via clinical visits. They included baseline and postprocedural electrocardiograms and echocardiograms. PPM implantation was considered in patients with persistent complete heart block after transcatheter heart valve (THV) deployment which did not spontaneously recover within 24 h. Decision of PPM after TAVR was made through consultation to an electrophysiologist at each site. The Cover index was calculated which is defined as: 100 × [(THV diameter 2 TEE annulus diameter)/THV diameter].6

3 CUSP OVERLAP TECHNIQUE

Cusp overlap views were derived via FluoroCT 3.0 imaging software (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc.) and confirmed under fluoroscopy during procedure by placing of pigtail catheter at the bottom of the NCC (Figure 1B). Prostheses were sized using manufacturer recommendations. After crossing the aortic arch with the nose cone of the delivery catheter, the catheter marker band was positioning at the midpoint of pigtail catheter to minimize left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) contact with the delivery system and allowing the valve to dive into the LVOT up to 2–3 mm below the annulus. Then, the valve was slowly deployed until the marker band reaches the third node of frame and then rapidly deployed from annular contact to point of no capture under rapid pacing to help increase valve stability (Figure 1C). The depth under the LCC was assessed by moving to a three-cusp coplanar view typically in the LAO position (no greater than 25°) and parallax at the inflow is minimized often by moving caudal (Figure 1D). Finally, after confirming valve position and performance, the valve is very slowly deployed as the outflow region leaves the capsule and the paddles release from the delivery system (Figure 1E).

4 STUDY OUTCOMES

The primary outcomes were the rate of new LBBB and PPM implantation during hospitalization and at 30 days. We also analyzed in-hospital and 30-day rate of moderate and severe aortic regurgitation and valve pop-out after final delivery.

5 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables between the groups were compared by Student's t test and categorical by the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with p < 0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the social sceinec statistics website.

6 RESULTS

A total of 519 patients were included in the cusp-overlap group versus 128 patients in the three-cusp group. Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Baseline RBBB was present in 10.4% and 13.2% (p = 0.35) in the cusp-overlap and three-cusp groups, respectively. The patients in the three-cusp group were at higher surgical risk, as reflected by society of thoracic surgery (STS) score (3.2 vs. 7.6; p ≤ 0.001) and logistic EuroSCORE (4.6 vs. 9.4; p ≤ 0.001).

| Patient characteristics | Cusp overlap view (n = 519) | Three cusp view (n = 128) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 82.8 (6.5) | 82.8 (6) | 0.94 |

| Female, n (%) | 232 (45) | 66 (51.5) | 0.163 |

| STS score, mean (SD) | 4.6 (3.2) | 7.6 (7) | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE, mean (SD) | 4.6 (4) | 9.4 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 175 (33) | 41 (32) | 0.716 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 389 (75) | 112 (87.5) | 0.002 |

| Coronary arterial disease, n (%) | 242 (46) | 70 (54.7) | 0.1 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 71 (14) | 35 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 54 (10.4) | 27 (21) | 0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 63 (12) | 39 (30.5) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension, n (%) | 32 (6) | 42 (33) | <0.001 |

| Active cancer, n (%) | 16 (3) | 5 (3.9) | 0.63 |

| NYHA class, n (%) | |||

| I | 32 (6) | 4 (3.1) | 0.178 |

| II | 255 (49) | 46 (36) | 0.007 |

| III | 212 (41) | 66 (51.5) | 0.028 |

| IV | 20 (3.8) | 12 (9.4) | 0.009 |

| Baseline RBBB, n (%) | 54 (10.4) | 17 (13.2) | 0.35 |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 58.4 (11.1) | 53 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Aortic valve area (cm2), mean (SD) | 0.74 (0.26) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.05 |

| Mean aortic valve gradient (mmHg), mean (SD) | 41.8 (16) | 42.8 (17) | 0.5 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve, n (%) | 19 (3.6) | 2 (1.6) | 0.23 |

- Abbreviations: LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RBBB, right bundle branch block; STS, society of thoracic surgery.

Procedural characteristics are shown in Table 2. AV calcium score was significantly higher in the cusp-overlap group (3888 vs. 2914; p = 0.046). Prostheses were sized using manufacturer recommendations; 31 mm valve was more frequently implanted in the three-cusp group (0% vs. 11.7%; p ≤ 0.001), and 34 mm valve was more frequently implanted in the cusp-overlap group (12.5% vs. 1.6%; p ≤ 0.001). When combined 31 and 34 mm valves, there is no significant difference between the groups (12.5% vs. 13%, p = 0.81). Transfemoral access was the predominant approach in both groups (99.2% vs. 98.4%; p = 0.4). Conscious sedation was used more in the cusp-overlap group (94.2% vs. 79.7%; p ≤ 0.001). Safari wire was used more in the cusp-overlap group, and Lunderquist and Confida wires were used more in the three-cusp group. Predilatation and postdilatation were used in 52% versus 20% (p ≤ 0.001) and 19% versus 22% (p = 0.47) in the cusp-overlap and three-cusp group. There were two (0.4%) versus three (2.3%) valves pop-out in the cusp-overlap and three-cusp groups after final delivery (p = 0.02). There was no significant difference between the two groups in the rates of bicuspid aortic valve (3.6% vs. 1.6%; p = 0.23) and valve-in-valve (9% vs. 11%; p = 0.46) TAVR procedures.

| Procedural characteristics | Cusp overlap view (n = 519) | Three cusp view (n = 128) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AV calcium score by CT, mean (SD) | 3888 (2404) | 2914 (2499) | 0.046 |

| AV perimeter (mm), mean (SD) | 75.6 (8) | 74.4 (9) | 0.15 |

| Valve size used, n (%) | |||

| 23 mm | 31 (6) | 10 (8) | 0.44 |

| 26 mm | 188 (36) | 43 (33.6) | 0.57 |

| 29 mm | 235 (45) | 58 (45) | 0.99 |

| 31 mm | 0 (0) | 15 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| 34 mm | 65 (12.5) | 2 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Cover index, mean (SD) | 14.9 (4.8) | 15.1 (4.9) | 0.67 |

| Approach, n (%) | |||

| Transfemoral | 515 (99.2) | 126 (98.4) | 0.4 |

| Subclavian | 3 (0.6) | 2 (1.6) | 0.25 |

| Trans-carotid | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Conscious sedation, n (%) | 489 (94.2) | 102 (79.7) | <0.001 |

| Type of wire, n (%) | |||

| Launderquist | 71 (13.7) | 65 (50) | <0.001 |

| Safari | 423 (81.5) | 32 (25) | <0.001 |

| Confida | 23 (4.4) | 32 (25) | <0.001 |

| Amplatz extra stiff | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Balloon predilatation, n (%) | 270 (52) | 26 (20) | <0.001 |

| Balloon postdilatation, n (%) | 99 (19) | 28 (22) | 0.47 |

| TAV-in-SAV | 46 (9) | 14 (11) | 0.46 |

| Device pop-out, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (2.3) | 0.02 |

| Need for second valve, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (2.3) | 0.06 |

- Abbreviations: AV, aortic valve; CT, computed tomography; SAV, surgical aortic valve; TAV, transcatheter aortic valve.

In-hospital and 30-day outcomes are shown in Table 3. In-hospital new LBBB occurred in 158 patients (30.4%) in the cusp-overlap group versus 37 patients (29%) in the three-cusp group (p = 0.73). The rate of in-hospital new complete heart block and PPM implantation were (9.4% vs. 23.4%; p ≤ 0.001) and (8% vs. 21%; p ≤ 0.001) in the cusp-overlap and three-cusp groups, respectively.

| Outcomes | Cusp overlap view (n = 519) | Three cusp view (n = 128) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital outcomes | |||

| New LBBB, n (%) | 158 (30.4) | 37 (29) | 0.73 |

| New complete heart block, n (%) | 49 (9.4) | 30 (23) | <0.001 |

| New permanent pacemaker, n (%) | 42 (8) | 27 (21) | <0.001 |

| Moderate/severe aortic regurgitation, n (%) | 13 (2.5) | 12 (9) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 59 (11) | 54.8 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| Aortic valve area (cm2), mean (SD) | 2 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.5) | 0.001 |

| Mean aortic valve gradient (mmHg), mean (SD) | 7.1 (4.3) | 7 (4.7) | 0.88 |

| Outcomes at 30 days | |||

| New LBBB, n (%) | 184 (35) | 38 (30) | 0.22 |

| New complete heart block, n (%) | 60 (11) | 30 (23) | <0.001 |

| New permanent pacemaker, n (%) | 53 (10) | 27 (21) | <0.001 |

| Moderate/severe aortic regurgitation, n (%) | 13 (2.5) | 8 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 60 (9.8) | 54.8 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Aortic valve area (cm2), mean (SD) | 1.8 (1) | 1.6 (0.5) | 0.04 |

| Mean aortic valve gradient (mmHg), mean (SD) | 8 (4.2) | 8.2 (4.7) | 0.65 |

- Abbreviations: LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

At 30 days, the rate of new LBBB was 35% versus 30% (p = 0.22). The rates of new complete heart block and PPM implantation were (11% vs. 23%; p ≤ 0.001) and (10% vs. 21%, p ≤ 0.001). Moderate and severe leak occurred in 2.5% vs 10% (p ≤ 0.001).

Among 53 patients with baseline RBBB in the cusp-overlap group, 19 patients (35%) required PPM. In the three-cusp group, eight out of 14 patients (57%) with baseline RBBB required PPM implantation (p = 0.19). Among patients with baseline LBBB, eight out of 54 patients (14.8%) in the cusp-overlap group required PPM implantation versus two out of 14 patients (14.2%) in the three-cusp group (p = 0.96).

7 DISCUSSION

In this restrospective analysis of two approaches to implantation of a SE TAVR prosthesis, we found a stasticially significant reduction in the occurrence of complete heart block, PM need, and PVL using a cusp overlap versus traditional three-cusp approach.

Conduction disturbances and the need for PPM implantation remain a frequent limitation of TAVR.1 Several preprocedural nonmodifiable factors (e.g., RBBB) have been associated with an increased risk for PPM. Valve type and implantation depth have been the most common modifiable procedural factors associated with conduction disturbances post-TAVR.1 Conduction disturbances, especially new-onset LBBB and PPM implantation have been associated with all-cause mortality and a higher risk of heart failure rehospitalizations after TAVR.7, 8 This represents a significant TAVR limitation, which is particularly relevant as TAVR is rapidly expanding toward younger and lower-risk patients.

Increased operator experience and new THV design improvements have been associated with significant reduction in PPM implantation rates.2, 8, 9 Although PPM implantation rates have been decreasing over the last years, new imaging understanding and techniques for implantation are warranted to decrease this periprocedural complication especially when treating young patients.

Several studies have confirmed a relationship between THV implantation depth in the LVOT and PPM implantation rate.9-11 The His bundle passes through the MS, a few millimeters beneath the NCC/RCCs.12 It is, therefore, not surprising that a deeper valve implantation increases the likelihood of mechanical damage of the His bundle, leading to a transient or persistent conduction disturbance.

In this study, we compared the conventional three-cusp view with a recently introduced right and left cusp-overlap view for SE valve implantation. We demonstrate that the rate of in-hospital PPM implantation is significantly lower when using the cusp overlap view. At 30 days, the rate of new LBBB was similar, but the rates of new complete heart block and PPM implantation were significantly lower in the cusp overlap group. This reduction in the rates of PPM implantation was significantly lower in the cusp overlap group despite higher rates of AV calcium score and predilatation, which are known independent predictors for PPM after TAVR.13, 14 We postulate this improvement in PPM rate in the cusp overlap implantation technique due to lower risk of interaction with the conduction system by providing a more accurate assessment of THV depth. The cusp overlap view provides a good anatomical reference for deployment depth at the point of THV contact (NCC) and elongates the outflow tract in a long-axis view. This assists with depth visualization near the nonright commissure and MS during deployment.

Our study's findings are consistent with the interim analysis of the first 171 patients treated in the OPTIMIZE PRO clinical study, which designed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of Evolute valves utilizing the cusp-overlap technique. They found a low pacemaker rate (8.8%) at 30 days. The rate of new LBBB at 30 days was 25.7%.15 In the recent study by Mendiz et al.16 who studied the impact of cusp-overlap view over conventional three-cusp view implantation for TAVR with Evolut SE valves on 30-day conduction disturbances in a cohort of 257 patients. They noted a significant reduction of both LBBB (12.9% vs. 5.8%; p = 0.05) and PPM implantation (17.8% vs. 6.4%; p = 0.004) rate with the cusp-overlap view in comparison with the traditional three-cusp view. In our study, we did not observe any reduction in the onset of new LBBB. A potential explanation for our discordant results is that we included patients with bicuspid valves and valve-in-valve procedures in our analysis, in contrast to this study. Another potential explanation for our discordant results is that the rates of both AV calcifications and balloon predilatation, which were identified as a risk factors for conduction abnormalities post TAVR,13, 14 were higher in the cusp-overlap group but were equally in both groups in Mendiz et al. study.

Another interesting observation in our study is that Lunderquist Extra Stiff wire was only used in 14% of the cusp overlap group. This is significantly lower than what was used in the OPTIMIZE PRO clinical study (65.3%). In our study, we used Lunderquist in the cusp overlap technique when greater support was required to deliver the TAVR device such as the presence of a horizontal aorta, valve-in-valve procedure, or using Evolut 34 mm valve. We hypothesize that a greater use of the Lunderquist wire (as in the OPTIMIZE PRO study), may have resulted in an even lower PPM implantation rate given the added support of the valve delivery system.

8 LIMITATIONS

Our study must be interpreted in the context of several limitations that merit discussion. This was a retrospective observational study, and the available data are subject to potential biases, such as selection bias. For example, there were significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. Given our small sample size, we were underpowered to do a risk-adjusted analysis, and, therefore, provide unadjusted results only. Similarly, procedural data such as the size of the prosthesis were not adjusted for. Another limitation is that certain previously identified predictors of PPM after TAVR, such as depth of valve implantation was not available in this data set and may be unbalanced between the groups. Also, Pacing dependency and pacing burden were not systematically evaluated on follow-up as this was not part of our abstraction data set. Finally, as we compared two different eras of TAVR, we cannot exclude that some of the improvements observed were a result of temporal improvements in the prosthesis and operator technical/experience. However, it is important to consider that all patients on the Cusp-overlap group were included during the learning curve of the operators with this new strategy and a low PPM implantation rate was achieved from the beginning of the experience. Also, the changing indications over these time period to include low-risk patients resulted into more lower risk patients treated with TAVR in the cusp-overlap group, as reflected by lower STS score and EuroSCORE, which may have accounted for the improved results.

9 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the cusp overlap technique offers several potential technical advantages compared to standard three-cusp approach, and may result in lower PPM rates in TAVR with Evolut SE valve, although imprecision remains as we provide unadjusted results only. Therefore, a larger prospective multicenter study, and probably randomized clinical trial would be needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this new implantation strategy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.