The impact of a statewide payment reform on transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) utilization and readmissions

Abstract

Background

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is an increasingly used but relatively expensive procedure with substantial associated readmission rates. It is unknown how cost-constrictive payment reform measures, such as Maryland's All Payer Model, impact TAVR utilization given its relative expense. This study investigated the impact of Maryland's All Payer Model on TAVR utilization and readmissions among Maryland Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods

This was a quasi-experimental investigation of Maryland Medicare patients undergoing TAVR between 2012 and 2018. New Jersey data were used for comparison. Longitudinal interrupted time series analyses were used to study TAVR utilization and difference-in-differences analyses were used to investigate post-TAVR readmissions.

Results

During the first year of payment reform (2014), TAVR utilization among Maryland Medicare beneficiaries dropped by 8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: −9.2% to −7.1%; p < 0.001), with no concomitant change in TAVR utilization in New Jersey (0.2%, 95% CI: 0%–1%, p = 0.09). Longitudinally, however, the All Payer Model did not impact TAVR utilization in Maryland compared to New Jersey. Difference-in-differences analyses demonstrated that implementation of the All Payer Model was not associated with significantly greater declines in 30-day post-TAVR readmissions in Maryland versus New Jersey (−2.1%; 95% CI: −5.2% to 0.9%; p =0.1).

Conclusions

Maryland's All Payer Model resulted in an immediate decline in TAVR utilization, likely a result of hospitals adjusting to global budgeting. However, beyond this transition period, this cost-constrictive reform measure did not limit Maryland TAVR utilization. In addition, the All Payer Model did not reduce post-TAVR 30-day readmissions. These findings may help inform expansion of globally budgeted healthcare payment structures.

1 INTRODUCTION

In light of improved outcomes and expanding applications for transcatheter aortic valve replacements (TAVR), it is important to understand whether there has been a concomitant increase in access to and utilization of this expensive procedure.1, 2 Maryland's healthcare payment structure allows for a case study of TAVR utilization in a policy-driven, cost-constrained system. In 2014, Maryland enacted a state-wide all-payer, globally budgeted system termed the All Payer Model.3-5 The key component of this model is the Global Budget Revenue (GBR), a policy that places caps on annual hospital expenditures.3, 6-8 Under this system, every hospital is assigned an annual budget for hospital-based care, with the goal of limiting overall costs as well as Medicare per capita expenditures.8 The model shifts focus from payment per inpatient admissions, to an all payer, per capita, total hospital bundled payment, thereby shifting from volume-based to value-based payments. Additionally, the All Payer Model also includes stipulations to reduce avoidable healthcare utilization, which involves a focus on lowering 30-day readmission rates.9 Under this model, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projected over $300 million savings in Medicare spending within 5 years.8 Given the All Payer Model's focus on reducing Medicare spending through global budgeting and reduced readmissions, it is critical to understand how this payment reform has impacted utilization of relatively expensive yet highly effective procedures with high readmission rates that are heavily used by Medicare beneficiaries, such as TAVR's.10, 11 Expanding access to novel therapies for patients with valvular heart disease is critically important, and thus an understanding of the impact of payment reform on TAVR utilization is critical for Maryland as well as other states considering similar value-based reform measures.12 Thus, this study examined the impact of Maryland's All Payer Model on TAVR utilization and readmissions among Maryland Medicare beneficiaries. Additionally, this study investigated whether this value-based, cost-containing payment reform limited the spread of TAVR procedures beyond academic centers in Maryland. TAVR data from New Jersey (a state similar in population demographics but with no global budgeting) were used for comparison to help control for underlying changes in indications for TAVR across the study period.13 We hypothesized that Maryland's All Payer Model resulted in decreased utilization of TAVR and reduced readmission rates among Medicare beneficiaries receiving TAVR. We also hypothesized that nonacademic centers would experience a greater change in TAVR utilization and readmission rates compared to academic centers.

2 METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of all Medicare beneficiaries in Maryland and New Jersey who underwent aortic valve replacement between July 2012 and December 2018. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

2.1 Study population

Maryland and New Jersey data were extracted from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project's (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID). Only Medicare patients who were residents of each state were included in study analyses. Patients undergoing aortic valve replacement were identified using the codes listed in Table 1. Of these patients, those who underwent TAVR were identified using the specific International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 and 10 procedure codes listed in Table 1. Crosswalks between ICD 9 and 10 codes were undertaken with the aid of our institutional Billing and Insurance Services Department, to ensure accuracy of code conversions. Among TAVR patients readmitted within 30 days after discharge from their index procedure, the primary diagnosis listed for the repeat admission was used to determine the cause for readmission. Patients readmitted for TAVR-related medical issues were selected using the most common post-TAVR readmission diagnoses reported in the literature.14 Any readmissions to rehabilitation facilities were excluded.

| Procedure | ICD-9 | ICD-10 |

|---|---|---|

| TAVR | 35.05–35.06 | 02RF37Z, 02RF38H, 02RF38Z, 02RF3JH, 02RF3JZ, 02RF3KH, 02RF3KZ, 02RH37H, 02RF3JH, 02RF47Z, 02RF48Z, 02RF4JZ, 02RF4KZ, and X2RF332 |

| SAVR | 35.21–35.22 | 02RF07Z, 02RF08Z, 02RF0JZ, 02RF0KZ, |

- Abbreviations: ICD, International Classification of Diseases; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

2.2 Study design: Maryland versus New Jersey

TAVR utilization in Maryland was compared to New Jersey to account for secular trends in TAVR utilization/outcomes across the study period (expansion of TAVR indications and patient selection, improved valve technology, lower complication rates). A comparative analysis of New Jersey and Maryland, allowed us to isolate the specific impact of the All Payer Model in Maryland on TAVR utilization/outcomes. New Jersey was selected as a comparison state as it is close in proximity geographically and has comparable demographics to Maryland, but it does not have hospitals that operate under global budgets.13 In this study, therefore, TAVR data from pre- and post-2014 (the year of All Payer Model implementation) were compared between the two states.

2.3 Statistical analyses

The two-tailed threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for post-hoc analyses. Demographic and clinical variables were compared within and between states using χ2 and Students’ t tests as appropriate. Two main outcomes were investigated: (1) TAVR utilization and (2) post-TAVR readmissions. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC).

2.4 TAVR utilization analyses

Longitudinal trends in TAVR utilization were analyzed among Medicare beneficiaries across the study period. TAVR utilization represented as the proportion of Medicare patients receiving TAVR among all Medicare patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. A two-step, multigroup interrupted time series design with variance-weighted linear regression modeling was used to investigate the impact of the All Payer Model on temporal changes in TAVR utilization among Medicare patients in Maryland versus New Jersey. The principal predictor in these models was the quarter (3-month period) during which the TAVR was performed over the years available for each state. Policy effects were estimated by comparing adjusted trends of TAVR utilization by Medicare beneficiaries between Maryland and New Jersey. The year 2014 was excluded from analyses as a washout period, given that the reform measures implemented in January 2014 may have taken at least 6 months to be fully implemented.

In the first step of the interrupted time series analysis, logistic regression models at the patient level were used to generate adjusted proportions of patients in Maryland versus New Jersey undergoing TAVR during each 3-month period (quarter) for the entire study period. The models controlled for patient-level factors (age, race, sex, comorbidity, and Area Deprivation Index—a validated measure of socioeconomic deprivation, reported at the level of census blocks) and hospital-level factors (hospital TAVR volume) that have been demonstrated to impact TAVR utilization in prior literature. We confirmed the model goodness-of-fit by calculating c-statistics.

In the second step of the analysis, we used adjusted proportions of quarterly TAVR utilization in an interrupted time series analysis with variance-weighted least squares regression. This model accounted for standard errors of the quarterly TAVR utilization estimates. Covariates in this model included a binary indicator for pre- versus postpayment reform time period, time as a continuous variable, and an interaction term between these two variables. The goodness of fit for these models was evaluated using visual inspection of observed versus expected plots. The regression model is depicted in the Supporting Information.

TAVR utilization was also assessed at the hospital level in Maryland to determine whether global budgeting limited the spreading of TAVR beyond urban teaching hospitals. χ2 analyses were used to analyze the distribution of hospital types (urban teaching, urban nonteaching, nonurban) at which Medicare patients received care pre- and postpayment reform. Additionally, maps of hospitals offering TAVR to Medicare beneficiaries in Maryland pre- and postreform were generated using Python 3.7.2 (Python Software Foundation).

2.5 TAVR readmissions analyses

The impact of the All Payer Model on 30-day readmission rates pre-and post-2014 was assessed using a quasi-experimental, linear regression difference-in-differences design. These analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, comorbidity, and hospital TAVR volumes, as well as for a linear quarterly time trend.15 Standard errors were clustered at the hospital level using cluster-correlated robust estimates of variance, accounting for clustering at the hospital level and autocorrelation of repeated measures across quarters. A binary indicator for payment reform status was created to indicate readmissions by state, and a second binary indicator variable was created to delineate readmissions that occurred post-2014 versus pre-2014. An interaction term between these two indicators served as the difference-in-differences estimator. To determine model validity, we assessed the four assumptions of difference-in-differences analyses, including exchangeability, positivity, stable unit treatment values assumption, and parallel trends in outcomes between New Jersey and Maryland before 2014. The basic model is described in the Supporting Information.

3 RESULTS

3.1 TAVR patient characteristics

Between July 2012 and December 2018, 13,169 Medicare patients underwent aortic valve replacement in Maryland, of whom 2028 (15.4%) underwent TAVR. Between July 2012 and December 2018, 11,623 Medicare patients underwent aortic valve replacement in New Jersey, of whom 2352 (20.2%) underwent TAVR. Characteristics of Maryland and New Jersey Medicare TAVR cohorts pre- and post-2014 are summarized in Table 2. Overall, Maryland and New Jersey TAVR cohorts only differed in terms of race, with a significantly greater proportion of TAVR patients in Maryland being African American compared to New Jersey (11.8% vs. 4.5%, p < 0.001).

| Characteristics | Maryland, n (%) | New Jersey, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2014 (n = 126) | Post-2014 (n = 1902) | p Value | Pre-2014 (n = 196) | Post-2014 (n = 2156) | p Value | p Valuea | |

| Sex | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.27 | ||||

| Male | 62 (49.2) | 926 (48.7) | 95 (48.5) | 1056 (49.0) | |||

| Female | 64 (50.8) | 976 (51.3) | 101 (51.5) | 1100 (51.0) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.48 | ||||

| <65 | 1 (0.8) | 8 (0.4) | 3 (1.5) | 5 (0.2) | |||

| 65–69 | 6 (4.7) | 102 (5.4) | 4 (2.0) | 95 (4.4) | |||

| 70–74 | 14 (11.0) | 212 (11.1) | 10 (5.1) | 250 (11.6) | |||

| 75–79 | 22 (17.3) | 348 (18.3) | 29 (14.8) | 368 (17.1) | |||

| 80–84 | 22 (17.3) | 522 (27.2) | 50 (25.5) | 610 (28.3) | |||

| >85 | 61 (48.4) | 710 (37.3) | 100 (51.0) | 828 (38.4) | |||

| Race | <0.001 | 0.22 | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 112 (88.9) | 1591 (83.7) | 179 (91.1) | 1958 (90.8) | |||

| Black | 5 (4.0) | 234 (12.3) | 7 (3.8) | 106 (4.9) | |||

| Asian | 2 (1.6) | 16 (0.8) | 2 (0.9) | 22 (1.0) | |||

| Other | 7 (5.5) | 61 (3.2) | 8 (4.1) | 71 (3.3) | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.08 | ||||

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 31 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 63 (2.9) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 126 (100.0) | 1871 (98.4) | 195 (99.5) | 2093 (97.1) | |||

| Marital status | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.12 | ||||

| Single | 10 (7.9) | 174 (9.2) | 10 (5.1) | 188 (8.7) | |||

| Married | 62 (49.2) | 913 (48.0) | 101 (51.6) | 962 (44.6) | |||

| Sep/divorced | 7 (5.6) | 122 (6.4) | 12 (6.1) | 123 (5.7) | |||

| Widower | 47 (37.3) | 693 (36.4) | 73 (37.2) | 875 (40.6) | |||

| Comorbidities | 122 (96.8) | 1837 (96.6) | 0.97 | 187 (95.4) | 2042 (94.7) | 0.34 | 0.06 |

| HTN | 84 (66.7) | 1169 (61.5) | 150 (76.5) | 1313 (60.9) | |||

| Immuno. | 0 (0.0) | 21 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (0.8) | |||

| PAD | 15 (11.9) | 147 (7.7) | 32 (16.3) | 334 (15.5) | |||

| CVD | 0 (0.0) | 41 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (1.0) | |||

| Cancer | 7 (5.6) | 25 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (0.5) | |||

| CAD | 76 (60.3) | 1260 (66.3) | 140 (71.4) | 1537 (71.3) | |||

| Liver disease | 2 (1.6) | 38 (2.0) | 4 (2.0) | 17 (0.8) | |||

| Sleep apnea | 10 (7.9) | 209 (11.0) | 14 (7.1) | 188 (8.7) | |||

| Syncope | 2 (1.6) | 18 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 24 (1.1) | |||

| Diabetes | 39 (31.0) | 628 (33.0) | 66 (33.7) | 796 (36.9) | |||

| CLD | 44 (34.9) | 468 (24.6) | 70 (35.7) | 584 (27.1) | |||

| Endocarditis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | |||

| Pneumonia | 2 (1.6) | 6 (0.3) | 8 (4.1) | 32 (1.5) | |||

| MI | 13 (10.3) | 69 (3.6) | 11 (5.6) | 78 (3.6) | |||

| ADI decile [mean ± SD] | 5.5 ± 2.4 | 5.5 ± 2.7 | 0.94 | 6.2 ± 3.1 | 6.2 ± 2.9 | 0.99 | 0.09 |

- Note: Bold values indicate p < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: ADI, area deprivation index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CLD, chronic lung disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; HTN, hypertension; Immuno, immunocompromized; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; SD, standard deviation; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

- a p Values comparing overall Maryland and New Jersey TAVR cohorts.

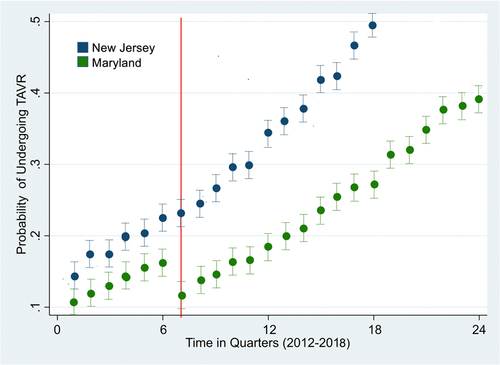

3.2 TAVR utilization—Longitudinal time series analysis

Logistic regression models were used to generate adjusted proportions of patients in Maryland versus New Jersey undergoing TAVR during each 3-month period (quarter) across the entire study period (Table 3). These models were then used in an interrupted time series analysis with variance-weighted least squares regression comparing TAVR utilization in Maryland and New Jersey between 2012 and 2018 (Table 4). This analysis demonstrated that TAVR utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in Maryland continued to increase post-2014, mirroring trends in New Jersey (Figure 1). Before payment reform, there was an increase in TAVR utilization among Maryland Medicare beneficiaries (1% increase per quarter; 95% confidence interval, or CI, 0.8%–1.2%, p < 0.001), and there was no significant change in this trend postpayment reform (post-2014 vs. pre-2014 change: 0.01% per quarter, 95% CI −0.01% to 0.03%, p = 0.06). Furthermore, when comparing Maryland to New Jersey, we found that the All Payer Model had no significant longitudinal policy effect. In other words, there was no significant difference in pre-2014 versus post-2014 trends of TAVR utilization when comparing Maryland and New Jersey (post-2014 vs. pre-2014 in Maryland vs. New Jersey: −0.1% per quarter, 95% CI −0.3% to 0.1%, p = 0.07).

| Maryland | New Jersey | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age | 1.2 (1.1–1.2) | 0.0001 | 1.2 (1.1–1.2) | 0.0001 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male (ref) | - | 0.001 | - | 0.0001 |

| Female | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | ||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White (ref) | - | - | - | - |

| Black | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.61 | 1.0 (1.0–1.2) | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 0.33 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.33 |

| Asian | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 0.07 | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.07 |

| Other | 0.6 (0.3–1.5) | 0.29 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.14 |

| Presence of comorbidity | 1.3 (1.1–1.9) | 0.007 | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) | 0.0001 |

| Hospital TAVR volume (%) | ||||

| First quartile (ref)a | - | - | - | - |

| Second quartile | 3.3 (1.1–1.7) | 0.0001 | 1.3 (1.2–1.6) | 0.0001 |

| Third quartile | 5.1 (3.9–6.6) | 0.0001 | 1.6 (1.5–1.8) | 0.0001 |

| Fourth quartile | 6.1 (4.5–8.3) | 0.0001 | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | 0.0001 |

- Note: Bold values indicate p < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve. replacement.

- a Quartile 1 represents hospitals with the lowest TAVR volume.

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% confidence interval | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maryland | |||

| Pre-2014 | 1.00% (0.30%) | (0.80%, 1.20%) | <0.001 |

| 2014 | −8.00% (1.00%) | (−9.20%, −7.10%) | <0.001 |

| Post-2014 versus pre-2014 | 0.01% (0.02%) | (-0.01%, 0.03%) | 0.06 |

| New Jersey | |||

| Pre-2014 | 1.00% (0.02%) | (1.00%, 2.00%) | <0.001 |

| 2014 | 0.20% (0.30%) | (-0.10%, 0.50%) | 0.09 |

| Post-2014 versus pre-2014 | 0.04% (0.10%) | (−0.06%, 0.14%) | 0.08 |

| Maryland versus New Jersey | |||

| Pre-2014 | −0.60% (0.02%) | (−1.10%, 0.50%) | 0.12 |

| 2014 (immediate policy effect) | −8.00% (1.00%) | (−9.20%, −7.10%) | <0.001 |

| Policy effect on pre–posttrends | −0.10% (0.20%) | (−0.30%, 0.10%) | 0.07 |

- Note: Bold values indicate p < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: SE, standard error; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

There was, however, a significant immediate policy effect noted in Maryland. Within the first year of payment reform, TAVR utilization among Maryland Medicare beneficiaries dropped by 8% (95% CI −9.2% to −7.1%; p < 0.001), but there was no comparable change in TAVR utilization among New Jersey Medicare beneficiaries during this time period (0.2%, 95% CI −0.1% to 0.5%, p = 0.09). This suggests that the All Payer Model had an immediate policy effect.

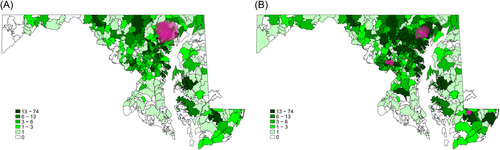

Hospital-level analyses were conducted in Maryland, to determine whether the All Payer Model limited the spread of TAVR utilization beyond academic centers in Maryland. The distribution of hospital types at which Medicare patients sought TAVR-related care differed significantly pre- and postreform: patients sought care at a wider range of hospital types post-2014. A significantly greater proportion of Medicare TAVR patients received care at nonacademic hospitals postreform, while almost all Medicare patients were treated at academic hospitals prereform (29% postreform, 2% prereform; p < 0.001). Maps were generated to demonstrate where Maryland Medicare beneficiaries sought TAVR-related care pre- (Figure 2A) and postreform (Figure 2B).

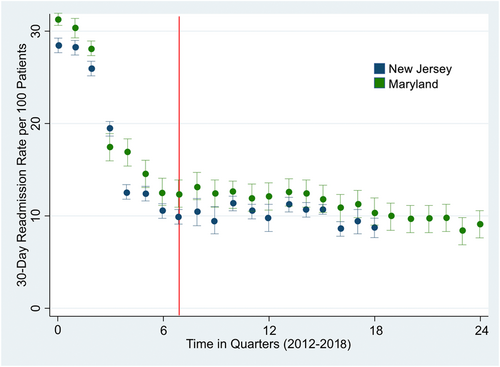

3.3 Post-TAVR readmissions—Difference-in-differences analysis

Figure 3 demonstrates trends in 30-day readmission rates. After performing an adjusted difference-in-differences analysis comparing Maryland to New Jersey, implementation of the All Payer Model was not associated with a significantly greater decline in 30-day post-TAVR readmissions in Maryland (−2.1%; 95% CI: −5.2% to 0.9%; p = 0.10; Table 5). Evaluation of the parallel trends assumption is demonstrated in Supporting Information: Table 1.

| Group | 30-day readmission rates per 100 TAVR patients (SD) | Difference-in-differences estimate (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2014 | Post-2014 | Difference in rates | Unadjusted | p Value | Adjusted | p Value | |

| Overall | |||||||

| Maryland | 14.9 (2.9) | 9.7 (2.0) | −5.2 | −2.7 (−5.2, 0.0) | 0.06 | −2.1 (−5.2, 0.9) | 0.10 |

| New Jersey | 12.8 (3.1) | 10.3 (2.7) | −2.5 | ||||

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve. replacement.

4 DISCUSSION

TAVR represents a critical evolution in the management of severe aortic valve stenosis.5, 16 Consequently, it is important to understand how healthcare payment reform, such as global budgeting, can impact TAVR utilization and outcomes. Such analyses could aid in evaluating the overall impact of reform measures, such as Maryland's All Payer Model, and could inform considerations for national scale-up as other states consider adopting similar models.

Across the study period, there were many global changes in TAVR-related care, in terms of patient selection, procedural techniques, device iterations, and perioperative patient management. We used New Jersey, a state similar in demographics to Maryland but without global hospital budgeting, as a comparison population to mitigate this issue. Both states experienced similar changes during the study period with regard to TAVR procedural refinement as well as with regard to expanding patient indications for TAVR. Thus, using New Jersey for comparison helped account for such underlying changes in TAVR utilization across the study period, allowing us to study the specific impacts of the All Payer Model.

Ultimately, we report several major findings. First, the implementation of a globally budgeted All Payer Model in Maryland did not stifle the utilization of TAVR among Medicare beneficiaries, and it did not limit the spread of this procedure beyond academic centers. This suggests that global hospital budgets do not suppress innovation or expansion of novel valve therapies. Second, although the Maryland All Payer Model was designed to reduce unnecessary healthcare spending (i.e., readmissions), we found no significant reductions in post-TAVR readmissions as a result of this policy implementation. Thus, while this model may reduce spending on a global level, states considering adopting global hospital budgeting may not see significant savings with regard to TAVR readmissions.

4.1 TAVR utilization in maryland continued to increase under the All Payer Model

Maryland's All Payer, globally budgeted system provides a unique case study of TAVR economics.6, 10, 17, 18 Under Maryland's system, global hospital budgets incentivize cost-effective care that optimizes clinical outcomes.19 Furthermore, through the All Payer Model, Maryland committed to reducing Medicare 30-day readmission rates through initiatives such as the Readmissions Reduction Incentive Program.20 Implementation of the All Payer Model in Maryland, therefore, engendered much concern among providers that global budgets and readmission penalties would discourage use of high-cost procedures with high readmission rates, such as TAVR.9, 19 Physician focus group participants specifically felt that the global budget reform had resulted in hospital leadership discouraging TAVR procedures.10

Despite a decrease in TAVR utilization within the first year of All Payer Model implementation, we ultimately found that global budgeting did not longitudinally impact TAVR utilization or adoption of TAVR across a variety of hospital types in Maryland. In fact, even after the implementation of the All Payer Model, we found that TAVR utilization by Medicare beneficiaries continued to increase in Maryland, mirroring trends seen in New Jersey. However, there was an immediate policy effect: TAVR utilization significantly declined in Maryland within the first year of All Payer Model implementation. This may have represented a learning curve for Maryland hospitals, as they adapted to global budgeting. Given that TAVR is a relatively expensive procedure with readmission rates as high as 17.9%, it is possible that hospitals were initially reluctant to budget for high TAVR volumes when transitioning to global budgets. In fact, the CMS anticipated the presence of such a “transition period” in 2014, and thus allowed hospitals to vary rates beyond the allowed amount to “learn how to operate within the new system.”21, 22

Our study confirmed the CMS's Second Annual Report on Maryland's All Payer Model, which reported that transcatheter valve replacements increased in the first 2 years after model implementation.10 By expanding the scope of the investigation beyond what was investigated in this CMS report, however, our study was able to demonstrate that the All Payer Model did not impose any longitudinal impact on TAVR utilization by Maryland Medicare beneficiaries. Our results also further expanded upon the CMS report to demonstrate that global budgeting did not discourage the spread of TAVR to nonacademic hospitals. Between 2012 and 2018, nonacademic hospitals nationwide began offering TAVR, as this procedure gained regulatory approval and began being used outside the realm of clinical trials. It was reassuring to see that nonacademic hospitals in Maryland also followed suit, despite having global budgets that may not have been as large as those of major academic centers.

Ultimately, the implications of these findings are encouraging; a common concern with cost-constraining healthcare reform measures is their potential implications for medical innovation or the adoption of novel medical procedures that may be more expensive. This concern may be particularly applicable to TAVR, a high-cost procedure performed on a high-risk patient population. Our investigation demonstrated that this was not the case with the Maryland All Payer Model, under which medical innovations such as TAVR continued to thrive and evolve despite global hospital budgeting.

While these results were encouraging for TAVR, a highly effective and life-saving procedure, it remains unclear whether these results are generalizable to other high-cost procedures, particularly procedures that impact only quality of life or more novel procedures with less supporting evidence. Further studies of the effects of global budgeting on other such procedures should be performed. Additionally, despite an index hospitalization cost of $47,196 for TAVR procedures, more recent data from the PARTNER 3 trial has demonstrated that TAVR is more cost-effective long-term compared to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), driven primarily by decreases in follow-up costs following hospital discharge.15 With these new results, we may expect to see further growth of TAVR in Maryland under a system that incentivizes cost savings. Future studies should be performed on the long-term effects of the Maryland All Payer Model on TAVR utilization.

4.2 The All Payer Model did not impact post-TAVR readmissions

Through the All Payer Model, Maryland committed to reducing avoidable admissions and complications, with a particular focus on Medicare 30-day unplanned readmission rates. This was done through initiatives such as the Readmissions Reduction Incentive Program, which provided rewards for reductions in readmission rates, as well as through greater care coordination, improvements in care transitions through the implementation of transitional case management programs, and a renewed focus on prevention.8, 20 Though global budgeting disincentivizes readmissions, our analyses demonstrated that Maryland Medicare beneficiaries undergoing TAVR did not have significantly greater declines in adjusted 30-day readmission rates after 2014 compared to their counterparts in New Jersey.13 This is in concordance with CMS's Final Report on the All Payer Model, which found that the All Payer Model did not impact readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries after all inpatient procedures.23 Our results specifically confirmed these trends for TAVR.

Prior literature has demonstrated that early readmissions (<30 days) after TAVR are largely related to periprocedural bleeding events. Thus, post-2014 declines in 30-day readmission rates in both states may reflect fewer periprocedural issues. This corresponds to the fact that over the years, improvements in TAVR technology/technique (including shorter procedure times, lower profile platforms and improved anesthetic management), have been demonstrated to reduce readmission rates among Medicare patients.24-27 Additionally, the decline in 30-day post-TAVR readmissions may also reflect the expansion of TAVR use to lower-risk patients, who naturally have lower clinical likelihoods of readmission.28, 29

Future work should investigate the impact of the All Payer Model on late readmissions (>30 days) after TAVR. Late readmission rates associated with TAVR are thought to be due to patient comorbidities more so than the procedure itself.14 It would be informative to investigate whether the All Payer Model's emphasis on improving coordinated care following hospitalization impacted the long-term health of TAVR patients.

4.3 Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this is an observational study and thus, it is possible that there were underlying time-varying confounders that could have explained the observed associations between the All Payer Model and differences in TAVR utilization and readmissions. For instance, as previously mentioned, longitudinal analyses of TAVR readmissions pre- and postpayment reform may have been confounded by underlying advancements in TAVR valve technology due to newer device iterations, improved procedural and periprocedural care of TAVR patients, and by expanding indications for TAVR from high risk to lower risk patients.16, 23, 24, 26, 28 We used New Jersey as a comparison population to mitigate this issue, and the trends noted in our study correspond with national published statistics of TAVR utilization. Also, we adjusted analyses for hospital TAVR volumes, which have been linked to provider skill/readmissions.24, 30 However, further multi-state studies are necessary to truly elicit the impact of the All Payer Model, especially as other states (e.g., Pennsylvania) are also adopting similar policy reform measures. Second, the data was limited to what is provided by the Maryland SID. The SID did not allow for the calculation of Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) scores, which is important to account for given that over the study period, TAVR became available for lower risk patients. However, this study did adjust for most of the major comorbid conditions identified by STS-PROM for aortic valve replacement.23 Last, although only Maryland residents were considered in our analyses, to minimize the likelihood that patients would pursue further care outside of the state, this data set did not capture readmissions of patients who moved out of the state after index TAVR procedures, and thus these patients may have been lost to follow-up.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study examined TAVR utilization/readmissions in Medicare beneficiaries pre- and postimplementation of Maryland's All Payer Model, with New Jersey used for comparison. Ultimately, we found that cost-constraining payment reform measures under the globally budgeted All Payer Model in Maryland did not stifle adoption/utilization of TAVR, despite its relatively high associated costs. However, although global hospital budgeting is designed to disincentivize readmissions, we found that TAVR-related readmissions did not decline in the postreform period. Such findings can help inform the national scale-up of such payment reform measures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.