Long-term follow-up of contemporary drug-eluting stent implantation in diabetic patients: Subanalysis of a randomized controlled trial

Abstract

Objective

The elevated risk of adverse events following percutaneous coronary intervention in diabetic patients persists with newer-generation DES. The polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (PF-AES) possesses characteristics with a potentially enhanced performance in patients with diabetes. Data from the 1-year follow-up period has been previously published. The aim of this subanalysis was to assess long-term performance of two contemporary drug-eluting stents (DES) in a diabetic population.

Methods

In the ReCre8 trial, patients were stratified for diabetes and troponin status, and randomized to implantation of a permanent polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent (PP-ZES) or PF-AES. The primary endpoint was target-lesion failure (TLF), a composite of cardiac death, target-vessel myocardial infarction and target-lesion revascularization. Clinical outcomes between discharge and 3 years follow-up were assessed.

Results

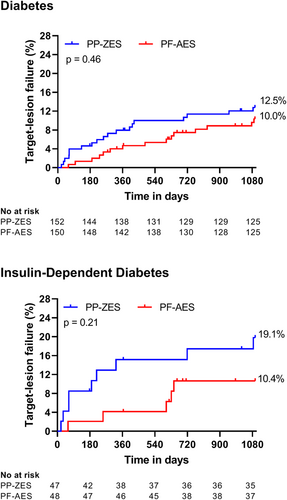

A total of 302 patients with diabetes were included in this analysis. After 3 years, TLF occurred in 12.5% of PP-ZES patients versus 10.0% in PF-AES patients (p = 0.46). Similarly, the separate components of TLF were comparable between the two study arms. The secondary composite endpoint of NACE was higher in the PP-ZES arm with 45 cases (29.6%) versus 30 cases (20.0%) in the PF-AES arm (p = 0.036). In the insulin-dependent diabetic population, TLF occurred in 19.1% of PP-ZES patients versus 10.4% of PF-AES patients (p = 0.21). NACE occurred in 40.4% of PP-ZES patients versus 27.1% of PF-AES patients (p = 0.10).

Conclusions

This subanalysis shows that the use of PF-AES results in similar clinical outcomes as compared to PP-ZES, yet some benefits of use of PF-AES in diabetic patients may prevail. Future dedicated trials should confirm these findings.

Abbreviations

-

- BARC

-

- Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

-

- DAPT

-

- dual antiplatelet therapy

-

- DES

-

- drug-eluting stent

-

- IDDM

-

- insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

-

- NACE

-

- net adverse clinical events

-

- PCI

-

- percutaneous coronary intervention

-

- PF-AES

-

- polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent

-

- PP-ZES

-

- permanent polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent

-

- TLF

-

- target-lesion failure

1 INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease is a common comorbidity in patients suffering from diabetes.1 Consequently, a substantial part of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is comprised of diabetics. The introduction of drug-eluting stents (DES) diminished adverse events in patients with diabetes2 to some extent. However, higher rates of adverse events following PCI are still reported specifically regarding revascularization.3 An ongoing effort is made to further reduce events in this population with often diffuse disease.

In the diabetic cohort of the ReCre8 trial, evaluation of 1-year clinical outcomes following implantation of a permanent polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent (PP-ZES) as compared to a polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (PF-AES) has been previously performed.4 Our hypothesis-generating results demonstrated a higher risk of net adverse clinical events (NACE) in diabetic patients, and a higher risk of both target-lesion failure (TLF) and NACE in insulin-dependent diabetics (IDDM) in the PP-ZES arm, as compared to the PF-AES arm.

These results were recently confirmed in a dedicated diabetes trial assessing performance of the successors of these two stents. The SUGAR trial5 demonstrated noninferiority of the Cre8 EVO stent as compared to the Resolute Onyx stent regarding TLF after 1 year, with superiority of the Cre8 EVO stent in an exploratory analysis.

The aim of the current subanalysis of the ReCre8 trial6 was to evaluate 3-year clinical outcomes following implantation of the PP-ZES versus PF-AES in an all-comers population with diabetes.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

The ReCre8 trial6 was a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial evaluating clinical outcomes following implantation of a PP-ZES (Resolute Integrity) and PF-AES (Cre8) in an all-comers population undergoing PCI. The Medical Ethics Research Committee Utrecht approved the execution of this trial, and approval was granted by the institutional review boards of each participating center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this trial.

A report on the study design has been previously published.6 Patients eligible for inclusion were stratified for history of diabetes and for troponin status at inclusion. Presence of diabetes was determined based on medical history and drug use. After stratification, patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to implantation of the PP-ZES or PF-AES. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) duration was prescribed for 1 month in patients with troponin-negative disease and 12 months in patients with troponin-positive disease. In this prespecified subanalysis, we report 3-year clinical outcomes after PCI of the diabetic subpopulation of the ReCre8 trial.

2.2 Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the ReCre8 trial was TLF, a composite endpoint of cardiac death, target-vessel myocardial infarction and target-lesion revascularization. The secondary composite endpoint of NACE was composed of death, any myocardial infarction, any unplanned revascularization, stroke and major bleeding (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3 or higher). In addition, the individual endpoint components were assessed separately. Clinical outcomes were defined according to definitions by the Academic Research Consortium7, 8 and have been previously described.9 Clinical outcomes were primarily assessed between hospital discharge and 3 years after PCI. In a secondary analysis, a landmark analysis on events occurring beyond 1 year was performed.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Kaplan–Meier time-to-event estimates were compared using log-rank test. Time-to–first-event was defined as the number of days between primary PCI and occurrence of any component of the endpoint. All analyses were performed on postdischarge events. Follow-up was censored at 3 years. Differences were considered statistically significant at a 2-tailed p value of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and all figures were generated using GraphPad Prism version 8.3 (GraphPad, Inc.).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Baseline and procedural characteristics

Patients in the ReCre8 trial were included between November 3, 2014 and July 10, 2017. A total of 304 patients in the Recre8 trial had a history of diabetes of which 302 remained for analyses after consent withdrawal of two patients. Baseline-, lesion-, and procedural characteristics have been previously published and were comparable between the study arms.4 Compliance of DAPT treatment was similar between the study groups.4

3.2 Clinical outcomes in PP-ZES versus PF-AES

Clinical outcomes for both study arms between hospital discharge and 3 years are shown in Table 1. Comparable rates of TLF were observed between the two arms: 12.5% of PP-ZES patients versus 10.0% of PF-AES patients (p = 0.46; Figure 1). NACE was higher in the PP-ZES arm with 29.6% versus 20.0% (p = 0.036). There were no statistically significant differences in the separate endpoint components. In total, two cases of stent thrombosis occurred out-of-hospital, both of which occurred in the PF-AES arm.

| Diabetes mellitus | Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 302) | PP-ZES (n = 152) | PF-AES (n = 150) | p Value | Overall (n = 95) | PP-ZES (n = 47) | PF-AES (n = 48) | p Value | |

| Target-lesion failure | 34 (11.3) | 19 (12.5) | 15 (10.0) | 0.46 | 14 (14.7) | 9 (19.1) | 5 (10.4) | 0.21 |

| Net adverse clinical events | 75 (24.8) | 45 (29.6) | 30 (20.0) | 0.036 | 32 (33.7) | 19 (40.4) | 13 (27.1) | 0.10 |

| All-cause death | 30 (9.9) | 15 (9.9) | 15 (10.0) | 0.98 | 17 (17.9) | 9 (19.1) | 8 (16.7) | 0.67 |

| Cardiac death | 15 (5.0) | 9 (5.9) | 6 (4.0) | 0.43 | 9 (9.5) | 6 (12.8) | 3 (6.3) | 0.26 |

| Myocardial infarction | 12 (4.0) | 4 (2.6) | 8 (5.3) | 0.25 | 6 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.5) | 0.016 |

| Target-vessel myocardial infarction | 7 (2.3) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (3.3) | 0.26 | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.3) | 0.092 |

| Stent thrombosis (definite or probable) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0.16 | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) | 0.35 |

| Any unplanned revascularization | 41 (13.6) | 25 (16.4) | 16 (10.7) | 0.11 | 14 (14.7) | 8 (17.0) | 6 (12.5) | 0.36 |

| Target-lesion revascularization | 17 (5.6) | 10 (6.6) | 7 (4.7) | 0.42 | 5 (5.3) | 3 (6.4) | 2 (4.2) | 0.56 |

| Stroke | 7 (2.3) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (2.0) | 0.68 | 5 (5.3) | 3 (6.4) | 2 (4.2) | 0.54 |

| Major bleeding (BARC ≥ 3) | 7 (2.3) | 6 (4.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0.059 | 3 (3.2) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.1) | 0.54 |

- Note: Clinical outcomes between hospital discharge and 3 years after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with diabetes and insulin-dependent diabetes. p values in bold indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

- Abbreviations: BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; PF-AES, Polymer-Free Amphilimus-Eluting Stent; PP-ZES, Permanent Polymer Zotarolimus-Eluting Stent.

Clinical outcomes in the subgroup of IDDM patients are shown in Table 1. TLF was not statistically significantly different with 19.1% of PP-ZES patients versus. 10.4% of PF-AES patients (p = 0.2; Figure 1). Similarly, no statistically significant difference was found between the two study arms regarding NACE (PP-ZES 40.4% vs. PF-AES 27.1%; p = 0.10). With the exception of myocardial infarction, all endpoint components were comparable between groups.

An additional landmark analysis was performed on events occurring between 1 year and 3 years following PCI (Supporting Information: Table 1). In these analyses, no statistically significant differences were found between the two study arms regarding neither TLF (5.0% vs. 6.9%; p = 0.48) nor NACE (17.1% vs. 14.6%; p = 0.55). A similar pattern was observed in the IDDM population, with no differences in any endpoint.

3.3 Clinical outcomes in nondiabetic-, noninsulin dependent diabetic- and insulin-dependent diabetic patients

Supporting Information: Table 2 shows clinical outcomes among patients with and without diabetes mellitus (DM) in the ReCre8 cohort after 3 years. TLF occurred more frequently in the diabetic subgroup with 90 cases in the non-DM group (7.6%) and 34 cases among DM patients (11.3%; p = 0.034). Similarly, NACE was higher among DM patients with 17.0% versus 24.8% (p = 0.002). Both all-cause- and cardiac death, and any unplanned revascularization were higher in the diabetic subpopulation.

Clinical outcomes after 3 years in non-IDDM and IDDM are shown in Supporting Information: Table 2. TLF occurred in 20 (9.7%) patients with non-IDDM and 14 (14.7%) patients with IDDM (p = 0.16). NACE occurred more frequently in the IDDM population with 20.8% versus 33.7% (p = 0.008). Both all-cause and cardiac death occurred more frequently after 3 years with 6.3% versus 17.9% (p = 0.001) and 2.9% versus 9.5% (p = 0.011).

4 DISCUSSION

The main findings of this prespecified subanalysis are (1) absence of statistically significant differences in TLF between patients implanted with the PP-ZES and PF-AES, (2) a higher rate of NACE among patients treated with the PP-ZES in the diabetic population between discharge and 3 years follow-up—a difference that appeared in the first year following PCI and persevered at longer-term follow-up, and (3) higher rates of NACE, all-cause- and cardiac death in diabetic patients as compared to nondiabetic patients, and in IDDM patients versus non-IDDM patients.

Results from the 1-year follow-up period of the diabetic patients in the ReCre8 trial have been previously published.4 Among diabetic patients, no difference in TLF was observed, however a higher NACE rate was observed in the PP-ZES arm. Among IDDM patients, both TLF and NACE were higher in the PP-ZES arm. In the 3-years results of the complete ReCre8 population,10 no significant differences were observed between the study stents. Both between 1- and 3 years follow-up, and during the total 3-year follow-up period, there were no differences in TLF or any other endpoints. Similar to these data, this subanalysis demonstrates no statistically significant difference in TLF across neither diabetic- nor IDDM patients. A higher rate of NACE in the PP-ZES arm between hospital discharge and 3 years is observed, confirming results from the first year of follow-up.

A great insight in performance of PP-ZES and PF-AES in diabetics is presented in the recently published results of the SUGAR trial.5 In this dedicated diabetes trial, patients were randomized for implantation of successors of the ReCre8 stents: the Resolute Onyx and Cre8 EVO stent. Noninferiority of the Cre8 EVO stent was demonstrated after 1 year and in addition, superiority was demonstrated in an exploratory analysis. Event rates among diabetic patients in this trial were higher compared to event rates in the ReCre8 trial, however rates are comparable when taking the ~4% of TLF in both stent arms in the first days into account. Interestingly, no significant difference in TLF between the stent arms was found among IDDM patients, a subgroup that showed a pronounced benefit of PF-AES implantation after 1 year in the ReCre8 trial.4

A prospective trial including patients undergoing PCI with implantation of second-generation DES11 reported comparable event rates for TLF-components among their diabetic population. Cardiac death occurred in 5% after 3 years (ReCre8 5.0%) and target-lesion revascularization in 5.5% (ReCre8 5.6%). Any revascularization was also comparable (13% vs. 13.6% in ReCre8). It should however be acknowledged that this trial assessed all events occurring post-PCI as compared to assessment of out-of-hospital events in the current analysis. The patient populations in which these numbers were generated share some similarities, however more previous MI and PCI were seen in the ReCre8 trial and a longer total stent length was implanted, whereas less multivessel disease was present. Of note is however that this trial excluded patient with a previous coronary artery bypass grafting.

A multigroup analysis on patients with and without diabetes with different stent-types12 reported clinical outcomes after 3 years in diabetic patients implanted with the PP-ZES. TLF was not reported, however cardiac death (4.5%) and target-lesion revascularization (5.1%) were reported and were lower as compared to PP-ZES patients in the ReCre8 trial (postdischarge 5.9% and 6.6% respectively). Although hypertension was similar at 73%, and multivessel disease was higher (57% vs. 46% in ReCre8), other important risk factors were considerably lower. Previous MI (7% vs. 28%), PCI (15% vs. 33%) and coronary artery bypass grafting (3% vs. 15%) as well as a positive family history (7% vs. 33%) were markedly higher in diabetic PP-ZES patients in the ReCre8 trial. Conversely, an analysis on all-comer diabetic patients in the BIO-RESORT trial13 implanted with the PP-ZES reported results more in line with the ReCre8 trial. After 2 years, TLF occurred in 9.7% of diabetic PP-ZES patients, as compared to 12.5% in ReCre8 after 3 years.

Results on long-term clinical outcomes in diabetics implanted with the PF-AES are more difficult to find. A subanalysis of the ISAR-TEST 5 trial14 assessed 5-year clinical outcomes in diabetics implanted with a polymer-free versus permanent polymer stent and reported no difference between the stents regarding TLF. High rates of target-lesion revascularization contributed to the high rates of TLF after 5 years of 33% in both arms. The protocol-mandated repeat angiography at follow-up is thought to have contributed to these high percentages. Furthermore, a distinct rise in events is visible at approximately 6 months following PCI, possibly due to cessation of the mandated antithrombotic treatment in the form of DAPT. An analysis on 5-year clinical outcomes in the NEXT trial15 showed no difference in TLF in the PF-AES arm between patients with and without diabetes (HR 1.04; 95% CI 0.320–3.374). The overall TLF rate in the PF-AES arm was 8.8%, however unfortunately no event rate for the diabetic subgroup was reported. Again, several important risk factors like hypertension (64% vs. 70%), prior myocardial infarction (9% vs. 27%), and prior PCI (16% vs. 24%) were lower in the PF-AES arm as compared to the diabetic PF-AES arm in ReCre8.

In a pooled analysis of the BIO-RESORT and BIONYX trials,16 clinical outcomes after implantation of contemporary DES in normoglycemic-, prediabetic- and diabetic patients were assessed after 3 years. TLF occurred in 5% of patients with normoglycemia and 11% of patients with diabetes (p < 0.001). When comparing these data, TLF among diabetic patients is similar however with exclusion of in-hospital events in our analysis. Several baseline risk factors among diabetics in the ReCre8 trial were higher (e.g., hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, previous MI), however more patients were treated for stable angina and less bifurcation- and small vessel lesions were present. Multivessel disease was similar in both studies. The TLF rate in the normoglycemic population however, was higher in the ReCre8 trial with 7.6% in our nondiabetic population. The fact that prediabetic patients are categorized in a separate subgroup in this trial, and are potentially included in the nondiabetic cohort of the ReCre8 trial, may have caused this difference. The prediabetic cohort in the aforementioned trial harbors a risk of TLF comparable to that of the diabetic population (10.2% vs. 11%) and may therefore represent an important subgroup for which special attention is warranted.

An explanation for the less distinctive results between the stent arms after 3 years follow-up may be found in the design and features of the PF-AES. The amphilimus formulation of sirolimus with long-chain fatty acids is thought to enhance uptake in diabetic cells as overexpression of membrane proteins increases fatty acid binding and translocation, which may in part overcome the relative resistance to -limus drugs of diabetic vascular smooth muscle cells.17 As complete elution of amphilimus is achieved after 90 days,18 after which it functions as a bare metal stent,19 the benefit of amphilimus can be expected in the first months and a reduced stent benefit at longer-term follow-up is comprehensible. Hopefully, future long-term results of the SUGAR trial will further elaborate on PF-AES performance in patients with diabetes.

4.1 Limitations

This subanalysis of the ReCre8 trial has several limitations. As it was a subanalysis, it was not powered to identify differences in subgroups. Any findings are therefore considered to be hypothesis-generating. Second, the presence of diabetes was assessed based on medical history and drug use at inclusion, causing a potential misclassification of patients with new diabetes. We however do not expect this to involve a large group with substantial influence significantly changing our results. Moreover, we believe the definition of diabetes used in the ReCre8 trial represents a real-world scenario as not all patients undergoing PCI will be screened for potential presence of diabetes. Furthermore, we did not assess glucose or HbA1c levels at inclusion and therefore were not able to evaluate patients with prediabetes in our cohort.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Based on this subanalysis, diabetic patients may benefit from implantation of the PF-AES. A benefit regarding NACE is established in the first year of follow-up and is maintained throughout 3 years following PCI. Future dedicated trials should confirm these findings. Persistent increased rates of adverse events following PCI in patients with diabetes offer ongoing opportunities to improve care in this complex population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all contributing research nurses, technicians, and personnel who contributed in the successful execution of this study. The authors express special thanks to Yvonne Breuer, Manager; Manon Kuikhoven, Clinical Research Coordinator; Marlies van Doleweerd, Clinical Research Coordinator; and Karen Vlaardingerbroek, Clinical Research Coordinator, Department of Research and Development, University Medical Center Utrecht, and all physicians involved in the execution of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.