Leave or stay? The role of self-construal on luxury brand attitudes and purchase intentions in response to brand rejection

Funding information: National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Numbers: 71772120, 71902060; Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China, Grant/Award Number: 2020JJ5375; Research Foundation of the Education Department of Hunan Province, China, Grant/Award Number: 19C1156

Abstract

Marketing managers of luxury brands often use exclusionary marketing tactics that can lead consumers to feel rejected by those brands. In our research, we examine whether consumers with independent self-construals are more likely than those with interdependent self-construals to downgrade their evaluations of a luxury brand when feeling rejected by it. Results of three studies support this hypothesis. Using a manipulation of brand rejection with hypothetical future scenarios, study 1 provides evidence that consumers with a higher chronic independent (versus interdependent) self-construal are more likely to lower their brand attitudes and purchase intentions of a desirable luxury brand that rejects them. Study 2 replicates the moderating effect of self-construal at a cultural level, comparing Chinese and American respondents. Study 3 again compares self-construals at a cultural level, but manipulates brand rejection by asking respondents to recall a prior rejection experience. Importantly, Study 3 reveals a mediating influence of self-brand connection. That is, independents, when recalling an experience of luxury brand rejection, were more likely than interdependents to report a decrease in their feelings of connectedness to the rejecting brand, which in turn resulted in lower attitudes toward the brand and lower purchase intentions. Our findings provide luxury brand marketers with insights for both niche branding strategy design and cross-cultural customer relationship management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Many consumers have had the experience of being rejected or excluded by a luxury brand, regardless of whether sellers of the brand intentionally or unintentionally meant to do so (Ward & Dahl, 2014). In marketing practice, consumers may be denied membership services, or they may feel that service employees display arrogance and reluctance to serve them. Although an abundance of marketing literature suggests that courteous and hospitable service can attract customers and increase their satisfaction and loyalty (e.g., Gremler & Gwinner, 2008), it is not uncommon in marketing of luxury brands for social exclusion to be used as a niche brand strategy (Wan & Bhatnagar, 2011). Interestingly, recent research challenges the conventional wisdom that a positive consumer experience in the buying process journey is always necessary for maintaining a strong brand, especially for a luxury brand (Wang, Chow, & Luk, 2013; Wang & Ding, 2017; Ward & Dahl, 2014). If a luxury brand has high brand awareness and well-established brand associations (Wang & Ding, 2017), or if the luxury brand's associations are related to a consumer's ideal self-concept (Ward & Dahl, 2014), perceived rejection by the brand will not necessarily lower consumers' desires for it.

Yet little is known about how culture, and consumers' views of themselves as independent or interdependent (i.e., their self-construal), affect consumers' responses to brand rejection. Luxury brands are a category in which sales differ significantly by culture (Demangeot et al., 2015), and Asian countries, in particular, continue to be lucrative markets for luxury products (Shukla, Singh, & Banerjee, 2015; Wang, Wu, Pechmann, & Wang, 2019). A large body of literature indicates that western consumers place more emphasis on hedonic experiences, personal tastes, and private meanings of luxury possessions. Asian consumers, in contrast, attach greater importance to social status, social propriety, and public meanings of luxury possessions (Schaefer, Hermans, & Parker, 2004; Shukla & Purani, 2012; Wong & Ahuvia, 1998) and may seek a feeling of uniqueness gained from owning luxury products (Bian & Forsythe, 2012).

Asian consumers may also be less reactive to exclusionary marketing tactics. Research on social exclusion suggests that consumers in emerging markets (i.e., China) may have favorable attitudes toward a luxury brand whose service employees display arrogance and excluding attitudes (Wang et al., 2013). However, no research contrasts consumers in different cultures or consumers with different self-construals in how they react to luxury brand rejection, and whether these reactions have favorable or unfavorable implications for luxury brand evaluations. Also unanswered is whether self-construal differences shape how consumers cope with brand rejection. Guidelines are needed for managers of luxury brands concerning in which cultural settings exclusionary marketing tactics should be maintained, and in which settings they should be avoided.

Our research examines the moderating effects of consumer self-construals (their independent or interdependent views of themselves and their culture of origin) on luxury brand rejection. We find that those consumers with higher independent (versus interdependent) self-construals, and those from the United States (versus China) have a greater likelihood of decreasing their brand attitudes and purchase intentions when feeling excluded by a luxury brand. We explore the underlying rationale for this finding by examining how consumers cope with exclusion through relationships with and/or perceived connection to the luxury brand. Consumers may build relationships with aspirational brands to achieve congruence between their image of the brand and their self-image (Sirgy, 1982), or to connect to other consumers who use the brand (Escalas & Bettman, 2003). Being rejected by a luxury brand might alter those connections with the rejecting brand, which in turn may affect evaluations of the brand. Our research extends literature on luxury brand rejection by proposing and testing this underlying process of self-brand connection (SBC) on responses of consumers with divergent self-construals. In particular, we find that differing responses to luxury brand rejection by consumers with independent (versus interdependent) orientations are driven by consumers' feelings of connection to the luxury brand, or self-brand connection. Our findings contribute to an understanding of how consumers' responses to luxury brand rejection can vary greatly by chronic and cultural self-construal, due to perceived strengthening or severing of ties to the brand, and these findings in turn have implications for marketing of those brands.

2 CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Social rejection and its consequences

Research in social psychology has suggested that interpersonal rejection thwarts the satisfaction of fundamental needs and consequently influences behaviors (Lee & Shrum, 2012; Williams, 2007). When being rejected, people receive explicit and direct signals concerning their poor standing within a relationship. Rejected individuals express greater interest in forging bonds with new social groups through prosocial behaviors (Lee & Shrum, 2012; Maner, DeWall, Baumeister, & Schaller, 2007), show more financial risk-taking tendencies (Duclos, Wan, & Jiang, 2013), and engage in impulsive behavior (Chester, Lynam, Milich, & DeWall, 2017). Specifically, being rejected may motivate people to consume strategically as a way of linking with others or a group (Mead, Baumeister, Stillman, Rawn, & Vohs, 2011). Rejected individuals may even wish to establish a relationship with anthropomorphized brands because these brands can help fulfill their needs for social affiliation (Chen, Wan, & Levy, 2017).

However, prior literature in psychology shows mixed results as to how people react to the perpetrator of rejection. Some research shows that excluded individuals feel dehumanized by others and report a lower sense of belonging (Bastian & Haslam, 2010). To protect themselves, people withdraw from social contact with those who reject them (Molden, Lucas, Gardner, Dean, & Knowles, 2009; Park & Baumeister, 2015). In contrast, other research with female participants finds that people continue to desire association with the rejecters and work harder to gain their acceptance after rejection (Williams & Sommer, 1997).

Recent research in marketing has also examined the coping mechanisms of rejected consumers (Hu, Qiu, Wan, & Stillman, 2018; Wang & Ding, 2017; Ward & Dahl, 2014). Ward and Dahl (2014) found that customers engaged in affiliative behaviors when being rejected by a desirable luxury brand to reaffirm their sense of self. Wang and Ding (2017) found that rejection did not impair consumers' commitment to a rejecting brand if that brand had high brand awareness and prestige (e.g., a luxury brand). Finally, research finds that when brand rejection is perceived to be legitimate, consumers rate the aspirational brand more favorably (Hu et al., 2018). These findings suggest that consumer responses to brand rejection can vary considerably depending on situational and individual factors.

2.2 Self-brand connections

Brands have symbolic meanings that extend beyond functional benefits of the brand (Fournier, 1998; Liu, Li, Mizerski, & Soh, 2012; Tsai, 2011; Zhu, Teng, Foti, & Yuan, 2019). This is particularly true for luxury brands, which are marketed for their brand image attributes (Kim, Lloyd, & Cervellon, 2016), such as prestige and exclusivity (Godey et al., 2016; Lee, Chen, & Wang, 2015; Parguel, Delécolle, & Valette-Florence, 2016). A variety of theories have argued that an understanding of consumers' responses to brands, and luxury brands in particular, can be gained by understanding how these brand images are related to a consumer's self-image (Escalas & Bettman, 2005; Sirgy, 1982; Sirgy et al., 1997). For example, some theories suggest that consumers compare the features of brands to their own features, choosing brands whose images are congruent with their own actual, ideal, or social self-images (called self-congruity theory; Malär, Herzog, Krohmer, Hoyer, & Kähr, 2018; Sirgy, 1982; Sirgy et al., 1997). Other theories argue that consumers form relationships with a particular brand to represent their values, to generate a sense of comfort (Escalas & Bettman, 2005), to demonstrate to others self-identities (Jacob, Khanna, & Rai, 2019; Huang, Chen, Wang, & Zeng, 2020) and therefore gain approval in social situations (Eastman, Shin, & Ruhland, 2020; Wilcox, Kim, & Sen, 2009), or to become associated with reference groups that are respected or valued by the culture (Berger & Ward, 2010). Given that luxury brands are marketed for their prestige and exclusivity, connecting with luxury brands, in particular, can signal a consumer's social status (Eastman et al., 2020; Jacob et al., 2019), covey a consumer's personal or cultural values (Ko, Costello, & Taylor, 2019), or even fulfill a consumer's need for uniqueness relative to peers (Butcher, Phau, & Shimul, 2017; Eastman et al., 2020). Being able to establish connections with consumers has been regarded as an essential feature in the success of marketing of luxury brands (Shimul, Phau, & Lwin, 2019).

Previous research shows that a consumer's feeling of connection to a brand is an important mediator and/or moderator of marketing effects on the consumer's brand attitude and behavior (Amaral & Loken, 2016; Moliner, Monferrer-Tirado, & Estrada-Guillén, 2018; Sicilia, Delgado-Ballester, & Palazon, 2016). This feeling of connectedness with a brand results in greater brand advocacy such that consumers communicate to others positive brand evaluations (Kemp, Childers, & Williams, 2012). When the self-brand connection of consumers is threatened (elicited by questioning of allegiance to their desirable brand, e.g., the Apple brand), consumers show a higher preference for the focal brand in order to strengthen the connection that is threatened (Angle & Forehand, 2016). When a luxury brand is used in a questionable context (e.g., by a conspicuous brand user), those with stronger connections to the brand are more likely to maintain their favorable responses of the brand (Ferraro, Kirmani, & Matherly, 2013). Similarly, those consumers with strong connections to a brand react defensively and have a higher need for belonging when the luxury brand is rejected by their social peers (Khalifa & Shukla, 2017). In the context of the present research, rejection by a desirable luxury brand might pose a threat to the consumer's connection to the brand, resulting in changes in brand preferences. We propose that moderating these changes in self-brand connections will be whether consumers view themselves as more independent or interdependent in orientation, discussed next.

2.3 Self-construal and responses to luxury brand rejection

Self-construal is the extent to which the self is defined as separate from others (independent) or connected to others (interdependent; Singelis, 1994). Individuals with predominantly an independent self-construal focus on the private self, internal attributes, and personal goals; conversely, those with predominantly an interdependent self-construal focus on the social self and public attributes, and highly value bonds with others (Gardner, Gabriel, & Lee, 1999). Differences in types and levels of self-construal can affect individuals' behaviors differently when their identities or relationships are threatened. Whereas interdependents tend to prefer identity-linked products when that identity is under threat, independents tend to avoid the existing identity connection in order to maintain positive self-worth (White, Argo, & Sengupta, 2012). Compared to independents, interdependents focus more on their brand relationships, and are more likely to forgive a transgressing brand (involved in product or service failures) with which they have strong connections (Sinha & Lu, 2016).

Although self-construal is an individual-level variable, culture is a powerful force in shaping this perception (Singelis, 1994). Westerners who have a higher independent self-view put more weights on self-regard and self-differentiation, expecting social relationships to be flexible and include a wider network of friendships; while Easterners who have a higher interdependent self-view define their self-concepts with respect to their group memberships, and emphasize harmony within the in-group (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Patterson, Cowley, & Prasongsukarn, 2006). Research shows that participants with individualistic backgrounds (e.g., Germans and Americans) have more antisocial and avoidance predispositions in response to exclusion, whereas participants with collectivistic backgrounds (e.g., Turks and Indians) do not (Pfundmair, Graupmann, Frey, & Aydin, 2015).

We propose that luxury brand rejection will, in a similar fashion, be influenced by a consumer's self-construal in strengthening or weakening feelings of connection to the brand, which in turn may lead to differing evaluative responses. Because luxury brands have high symbolic value (Stokburger-Sauer & Teichmann, 2013), consumers often establish relationships with them. But when the luxury brand-consumer relationship is threatened by brand exclusion, interdependents, who wish to keep their valued membership group, will continue to pursue a harmonious self-brand connection rather than seek to break the connection (referred to as self-differentiation). In contrast, independents may forego the broken relationship involving the brand; instead, they may differentiate themselves from the rejecting brand either as a form of ego-protection or because of the signaling effect of rejection and their lower need for affiliation. As a result, we expect that independents will decrease their brand attitudes and purchase intentions of the rejecting luxury brand's products:

H1.The effect of luxury brand rejection on consumer responses is moderated by self-construal. Specifically, when being rejected by a desirable luxury brand, consumers with a dominant independent self-construal are more likely than those with a dominant interdependent self-construal to lower their brand attitudes and purchase intentions of the rejecting brand's products.

H2.Self-brand connection will mediate the interaction effect of luxury brand rejection and self-construal on consumers' brand attitudes and purchase intentions (proposed in H1).

We conducted three studies to test the proposed hypotheses. In Study 1, we manipulated brand rejection with a hypothetical future scenario and measured chronic self-construal in order to test the effects of self-construal on consumer responses toward luxury brand rejection. In Study 2, we again examined the moderating effect of self-construal but at a cultural level. Study 3 tested the robustness of findings for a second brand rejection manipulation, with a recall and writing task of a prior rejection experience. Additionally, Study 3 provided evidence of the mechanism underlying the interaction effect of luxury brand rejection and self-construal on consumer responses.

3 STUDY 1

3.1 Subjects and design

Ninety-eight Chinese participants (42.9% females; Mage = 30.1) were recruited from the participant panel of a Chinese professional online survey platform Sojump (www.sojump.com, see Chen & Huang, 2016) and were paid a small monetary compensation. The study used a 2 (brand rejection: rejected vs. control) × 2 (self-construal: independent vs. interdependent) between-subject design, with brand rejection manipulated as a between-subjects variable and self-construal measured.

3.2 Stimuli and procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to either a social rejection or control condition, and were asked to complete two tasks, ostensibly unrelated: a personality test and a luxury brand survey. In the first task, participants indicated their self-construal tendencies with a standard Self-Construal Scale (Singelis, 1994). At the beginning of the second task, all participants responded to a brand elicitation procedure adapted from Wilcox et al. (2009). They were asked to name a favorite luxury brand, reported whether they had ever owned this brand and, in a hypothetical scenario, were asked to imagine certain benefits of applying for the named luxury brand's new membership card (Appendix A). Next, participants in the brand rejection (but not control) condition were asked to imagine submitting an application and receiving a rejection through email. This manipulation is consistent with paradigms used in prior research, which include Ball Tossing, Cyberball, getting acquainted, and reliving or imagining rejection experiences (see Williams, 2007 for a review).

Next, participants completed measures of brand attitude and purchase intention. They also indicated to what extent they felt rejected. Finally, participants provided some demographic information, were thanked for participating, and dismissed. All of the materials were translated into Chinese by two bilingual researchers using the back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1970).

3.3 Measures

We employed the 24-item Self-Construal Scale (SCS) developed by Singelis (1994) to assess participants' chronic self-construal (as differentiated from manipulating self-construal). In particular, 12 items measured independent self-construal (e.g., “I enjoy being unique and different from others in many respects”; α = .86), and 12 items measured interdependent self-construal (e.g., “It is important for me to respect decisions made by the group”; α = .88). We constructed the following self-construal index: (interdependent – independent)/(interdependent + independent), based on prior research (Chen & Huang, 2016; Winterich & Barone, 2011). A higher score reflects a dominant interdependent self-construal, while a lower score reflects a dominant independent self-construal. We measured brand attitudes with three items (e.g., “This brand is favorable”; α = .92; Labroo & Nielsen, 2010; Torelli, Monga, & Kaikati, 2012). Purchase intentions were measured with three of the following items. (e.g., “If I have enough money, I'm likely to purchase the products of this brand,” α = .94; Hung et al., 2011). All items used seven-point scales ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 7(strongly agree). Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics and correlations among variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Brand rejection condition | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Independent self-construal | .11 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3. Interdependent self-construal | .07 | .59** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4. Brand attitude | −.06 | .18 | .49** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. Purchase intention | −.13 | .18 | .47** | .90** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6. Brand ownership | −.13 | −.07 | −.06 | .00 | .02 | 1.00 | |||

| 7. Perceived rejection | .70** | .20* | .00 | −.10 | −.18 | .05 | 1.00 | ||

| 8. Gender | .00 | .08 | .05 | .06 | .03 | −.13 | .05 | 1.00 | |

| 9. Age | .11 | −.22* | −.29** | −.10 | −.14 | −.27** | .05 | .05 | 1.00 |

| Mean | — | 5.39 | 5.61 | 5.92 | 5.83 | — | 4.38 | — | 29.93 |

| SD | — | .92 | .99 | 1.06 | 1.14 | — | 1.74 | — | 5.53 |

- *p < .05; **p < .01.

3.4 Results and discussion

3.4.1 Manipulation check

The results of ANOVA on the perceived brand rejection indicated that participants in the rejected condition reported feeling more rejected than those in the control condition (Mrej = 5.59 vs. Mcon = 3.16, F(1, 97) = 93.40, p < .01, η2p = .49). Thus, the manipulation of brand rejection was successful.

3.4.2 Hypothesis tests

Brand attitude was regressed on brand rejection (dummy coded: 1 = rejection, 0 = control), the self-construal index, and the interaction effect, with gender, age and brand ownership as control variables. No significant effects of gender, age, or brand ownership were found, so these variables will not be discussed further.

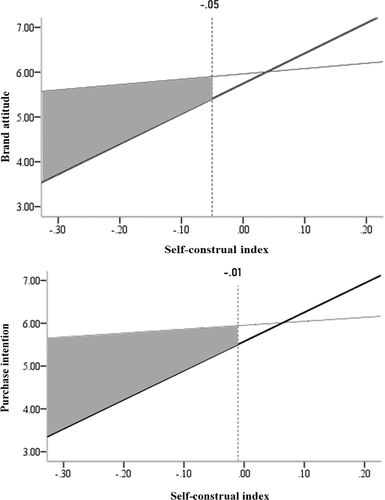

Consistent with predictions, a significant rejection condition × self-construal index interaction effect was found for brand attitude (β = .36, t = 2.45, p = .02, f2 = .26) (see Table 2). Likewise, a rejection condition × self-construal index interaction effect emerged for the regression of purchase intention (β = .35, t = 2.39, p = .02, f2 = .25) (see Table 2). Results of floodlight analyses using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Krishna, 2016; Spiller, Fitzsimons, Lynch Jr, & McClelland, 2013) showed that luxury brand rejection had a significant negative effect on brand attitude when values of self-construal index were below −.05 (bJN = −.50, SE = .25, p = .05), and had a significant negative effect on purchase intention when values of self-construal index were below −.01 (bJN = −.45, SE = .22, p = .05). Shaded regions in Figure 1 indicate the ranges of significance. Therefore, consistent with H1, being rejected had a negative effect on brand attitudes and purchase intentions among consumers with a high independent construal, but did not change the responses of those with a high interdependent self-construal.

| Variables | Brand attitude | Purchase intention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Main effect | ||||||

| Brand rejection | −.05 | .20 | −.49 | −.11 | .21 | −1.14 |

| Self-construal index | .10 | .16 | .65 | .06 | .17 | .43 |

| Interaction effect | ||||||

| Brand rejection × self-construal index | .36 | .20 | 2.45* | .35 | .22 | 2.39* |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Gender | .09 | .20 | .99 | .06 | .22 | .52 |

| Age | −.07 | .10 | −.68 | −.10 | .11 | .32 |

| Brand ownership | .00 | .23 | .00 | .00 | .24 | .99 |

| R2 | .21 | .20 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | .16 | .14 | ||||

- *p < .05; **p < .01.

In this first study, individuals' chronic self-construals were measured using the Singelis (1994) Self-Construal Scale. In Study 2, we use a cross-cultural design to further test the effect of self-construal by comparing Caucasian American and Chinese participants.

4 STUDY 2

4.1 Subjects and design

One hundred and twenty-eight Caucasian American participants (53.9% females; Mage = 34.9) on MTurk and one hundred and twenty-seven Chinese participants (59.8% females; Mage = 30.9) on the Chinese online survey platform Sojump were recruited to participate in our study. This study followed a 2 (brand rejection: rejected vs. control) × 2 (ethnocultural group: Caucasian Americans vs. Chinese, or independent vs. interdependent) between-subjects design.

4.2 Stimuli and procedure

Participants were first asked to complete an ostensibly unrelated personality test, to verify that Caucasian American and Chinese participants have different self-construal orientations. Additionally, some research has shown that people who are low in trait self-esteem are more sensitive to perceived rejection (Murray, Rose, Bellavia, Holmes, & Kusche, 2002); thus, we measured and included trait self-esteem as a covariate in our analyses. We adopted the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenburg, 1965) to measure trait self-esteem (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”; α = .85). In the second task, participants completed a luxury brand survey in which they named a favorite luxury brand and indicated whether they had ever owned this brand. The top three luxury brands Caucasian American participants mentioned were BMW (15.6%), Rolex (9.4%) and Chanel (8.6%), and those mentioned most frequently by Chinese participants were Louis Vuitton (15.0%), BMW (12.6%) and Rolex (9.4%). Next, participants were randomly presented with one of the hypothetical scenarios used in Study 1 (Appendix A), and then completed the same dependent measures as in Study 1. Finally, participants provided demographic information, and were thanked for participation.

4.3 Results and discussion

4.3.1 Manipulation check

As expected, participants in the rejected condition reported feeling more rejected than those in the control condition (Mrej = 5.10 vs. Mcon = 3.37, F(1, 254) = 61.89, p < .01, η2p = .20). Perceived rejection of American participants did not differ from that of Chinese participants (MAme = 5.27 vs. MChi = 4.94, F(1,124) = 1.25, NS, η2p = .01). American participants were more independent, while Chinese participants were more interdependent (MAme = −.06 vs. MChi = .02, F(1,254) = 21.83, p < .01, η2p = .08).

4.3.2 Hypothesis tests

A brand rejection (rejected vs. control) × ethnocultural group (Caucasian Americans vs. Chinese) MANCOVA was performed, using gender, age, trait self-esteem, and brand ownership as covariates. Trait self-esteem (Wilks's lambda = .96, F(1, 254) = 5.78, p < .01, η2p = .05) had a simple effect, but did not interact with the independent variables, so is not discussed further. Results indicated that culture (Wilks's lambda = .87, F(1, 254) = 18.17, p < .01, η2p = .13) and brand rejection (Wilks's lambda = .94, F(1, 254) = 8.33, p < .01, η2p = .06) had main effects on consumer responses. Of greater importance, a significant interaction effect between brand rejection and culture was obtained (Wilks's lambda = .95, F(1, 254) = 7.07, p < .01, η2p = .05). Follow-up ANCOVA tests revealed that the culture × brand rejection effect was significant for brand attitude (F(1, 254) = 13.86, p < .01, η2p = .05) and purchase intention (F(1, 254) = 9.02, p < .01, η2p = .04). As anticipated, American participants in the rejected condition had lower brand attitudes (Mrej = 4.61 vs. Mcon = 5.74, F(1,127) = 19.79, p < .01, η2p = .14) and lower purchase intentions (Mrej = 3.74 vs. Mcon = 4.96, F(1,127) = 15.14, p < .01, η2p = .11) than those in the control condition. However, differences between the two conditions were non-significant for the Chinese participants (i.e., interdependents) (brand attitude: Mrej = 5.81 vs. Mcon = 5.78, F(1,126) = .01, NS, η2p = .00; purchase intention: Mrej = 5.52 vs. Minc = 5.68, F(1,126) = 1.09, NS, η2p = .01). Tables 3 and 4 show the pattern of results. In sum, these results again corroborate H1.

| Variables | Multivariate | Univariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks's lambda | F | Brand attitude (F) | Purchase intention (F) | |

| Study 2 | ||||

| Main effect | ||||

| Brand rejection | .94 | 8.33** | 13.57** | 14.72** |

| Ethnocultural group | .87 | 18.17** | 19.53** | 36.37** |

| Interaction effect | ||||

| Brand rejection × Ethnocultural group | .95 | 7.07** | 13.86** | 9.02** |

| Covariates | ||||

| Gender | .97 | 3.43* | .01 | 3.57 |

| Age | 1.00 | .42 | .02 | .57 |

| Brand ownership | .97 | 3.95* | .06 | 3.44 |

| Self-esteem | .96 | 5.78** | 10.25** | 9.37** |

| Study 3 | ||||

| Main effect | ||||

| Brand rejection | .88 | 14.15** | 28.00** | 14.86** |

| Ethnocultural group | .85 | 18.36** | 11.94** | 36.66** |

| Interaction effect | ||||

| Brand rejection × Ethnocultural group | .95 | 5.06** | 9.43** | 6.79** |

| Covariates | ||||

| Gender | .99 | .86 | .33 | .31 |

| Age | .96 | 4.17* | 8.15** | 2.05 |

| Brand ownership | .88 | 13.61** | 1.90 | 22.88** |

- *p < .05; **p < .01.

| American participants | Chinese participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independents | Interdependents | |||

| Rejected | Control | Rejected | Control | |

| Study 2 | ||||

| Brand attitude | 4.61a (1.86) | 5.74a (.90) | 5.81NS (1.10) | 5.78NS (1.10) |

| Purchase intention | 3.74a (1.94) | 4.96a (1.75) | 5.52NS (1.37) | 5.68NS (1.07) |

| Study 3 | ||||

| Brand attitude | 4.86a (1.88) | 6.18a (.88) | 5.66b (.71) | 6.10b (.81) |

| Purchase intention | 4.18a (2.01) | 5.53a (1.42) | 5.32NS (1.03) | 5.94NS (.94) |

- Note: Numbers in parentheses are SDs.

- a Significantly different at p < .01, for differences between the rejected condition and the control condition.

- b Significantly different at p < .05, for differences between the rejected condition and the control condition.

- *p < .05; **p < .01.

Using a cross-country approach to operationalize self-construal, Study 2 suggests that people who differ on independent and interdependent self-construal due to cultural differences adopt distinct response strategies to luxury brand rejection. Study 3 builds on and extends these findings in three ways. First, Study 3 replicates the results with an alternative manipulation of brand rejection by having participants recall an actual rejection experience. Second, while the first two studies employ a control group (an absence of brand rejection), Study 3 contrasts the experience of brand rejection with the experience of brand inclusion. Third, Study 3 further explores the mechanism underlying these different responses to rejection by examining the mediating role of feelings of connection to the luxury brand.

5 STUDY 3

5.1 Stimuli and procedure

In order to assess the effects of social rejection using actual prior experience, a screener was required in order to include only individuals who (a) had recently purchased a luxury brand and (b) either had an experience of feeling rejected by the brand or had a favorable experience with the brand. The final sample sizes for those meeting the screening criteria were 107 Caucasian American participants (49.5% females; Mage = 39.0) on MTurk and 109 Chinese participants (57.8% females; Mage = 31.6) on Sojump.com. In this study, we used cultural background as a proxy for self-construal, in a 2 (brand rejection: rejection vs. inclusion) × 2 (ethnocultural group: Caucasian Americans vs. Chinese, or independent vs. interdependent) between-subjects design.

To manipulate brand rejection versus inclusion, all participants were asked to complete a recall and writing task adapted from prior research (Molden et al., 2009). (See Appendix B.) Participants in the brand rejection condition were asked to recall their recent past experience of being rejected by a desirable luxury brand, and were given 3 minutes to write a description of this incident. Participants in the brand inclusion condition were asked to write about their recent experience of successfully purchasing a desirable luxury brand, again for 3 minutes. The top three luxury brands Caucasian American participants mentioned were Chanel (8.4%), BMW (7.4%), and Rolex (7.4%) and those mentioned most frequently by Chinese participants were Louis Vuitton (22.9%), Chanel (21.1%), and Rolex (5.6%).

Participants completed measures of brand attitude and purchase intention (as in Study 1), and the SBC measure using a seven-item scale (e.g., “I feel a personal connection to this luxury brand”; α = .95; Escalas & Bettman, 2003, 2005). Finally, in addition to a manipulation check question, brand ownership and demographic information were added to our list of covariates.

5.2 Results and discussion

5.2.1 Manipulation check

As expected, participants in the rejected condition reported feeling more rejected than those in the inclusion condition (Mrej = 5.05 vs. Mcon = 2.76, F(1, 215) = 109.15, p < .01, η2p = .34). Perceived rejection of American participants did not differ from that of Chinese participants (MAme = 5.19 vs. MChi = 4.90, F(1,104) = .99, NS, η2p = .01).

5.2.2 Hypothesis tests

We performed a MANCOVA on the measures of consumer responses, with gender, age, and brand ownership as covariates. Two covariates, brand ownership (Wilks's lambda = .88, F(1, 215) = 13.61, p < .01, η2p = .12) and age (Wilks's lambda = .96, F(1, 215) = 4.17, p < .05, η2p = .04) had simple effects, but did not interact with any of the other variables, so will not be addressed further.

Results showed that the brand rejection × culture was significant on brand attitude (F(1, 215) = 9.43, p < .01, η2p = .04) and purchase intention (F(1, 215) = 6.79, p < .01, η2p = .03). Specifically, American participants in the rejected condition had lower brand attitudes (Mrej = 4.86 vs. Minc = 6.18, F(1,106) = 22.61, p < .001,η2p = .18) and lower purchase intentions toward the rejecting luxury brand (Mrej = 4.18 vs. Minc = 5.53, F(1,106) = 13.82, p < .001, η2p = .12) than those in the inclusion condition. Chinese participants in the brand rejection versus brand inclusion conditions also showed a significant difference for brand attitude, albeit a smaller difference than found for American participants (Mrej = 5.66 vs. Minc = 6.10, F(1,108) = 4.19, p = .04, η2p = .04), and as predicted, showed no significant differences for purchase intention (Mrej = 5.32 vs. Minc = 5.94, F(1,108) = 3.65, NS, η2p = .03) (see Tables 3 and 4). In sum, these results are consistent with H1.

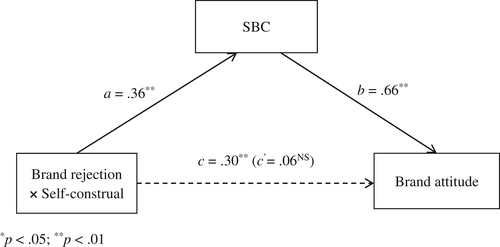

5.2.3 Mediation analysis

To examine whether SBC mediated the interaction effect between brand rejection and self-construal on consumer responses, we performed a mediated moderation analysis for brand attitude and purchase intention measures separately (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005). With regard to brand attitude, the results showed that the interaction between brand rejection and self-construal significantly predicted brand attitude (β = .30, t = 2.79, p < .01, f2 = .20) and SBC (β = .36, t = 3.50, p < .01, f2 = .35). Notably, the brand rejection × self-construal interaction was no longer significant when the mediator (SBC) was included as a predictor of brand attitude (p > .1), yet the main effect of SBC remained significant (β = .66, t = 11.71, p < .001, f2 = .99). A 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect (PROCESS Model 8) (Hayes, 2013) did not include zero (indirect effect ab = .23, 95% CI = [.27, 1.15]). A similar analysis was employed for purchase intention, and the results again confirmed a significant mediating effect of SBC (indirect effect ab = .24, 95% CI = [.36, 1.44]) (see Figure 2). Taken together, these results supported the prediction in H2.

Study 3 again confirmed that independents react more negatively than interdependents when rejected (versus not) by a luxury brand. Moreover, this study provides evidence that independent (versus interdependent) consumers have lower feelings of connection to the luxury brand, when rejected by it, and that this lower connection results in more negative responses toward the brand.

6 GENERAL DISCUSSION

The present research findings are the first empirical demonstration to show that independents react very differently to luxury brand rejection compared to interdependents. Across three experiments, the effect of self-construal as a moderator of consumers' responses to luxury brand rejection consistently emerged. In particular, independents were more likely to disconnect or differentiate themselves from the rejecting luxury brand, and the feeling of less connection to the brand contributed to lower attitudes toward the luxury brand and lower purchase intentions. Interdependents, in contrast, did not go through the process of disconnecting from the luxury brand; instead, they tended to continue to have the same level of favorability toward the brand. These results emphasize the point that being rejected by a luxury brand does not always discourage consumers; rather, the effects of connection to the brand in the face of rejection vary, depending on the consumer's dominant type of self-construal.

6.1 Theoretical and managerial contributions

The current research contributes to the literature on social exclusion effects in the domain of consumption. Recent work has found that interpersonal exclusion can influence consumers' product preferences, such as increasing individuals' interest in nostalgic products (Loveland, Smeesters, & Mandel, 2010), preferences for distinctive products (Wan, Xu, & Ding, 2013), or rates of conspicuous consumption (Lee & Shrum, 2012; Liang, He, Chang, Dong, & Zhu, 2018). Our findings enrich this line of research by examining consumers' reactions when the source of the exclusion is a luxury brand.

Second, we extend self-construal theory by identifying cultural differences in how independents and interdependents cope with luxury brand rejection, which has been rarely studied in the existing literature (Williams, 2007). While recent research suggests that how consumers respond to brand rejection depends on the type of brand (e.g., whether it has high brand awareness and well-established brand associations; Wang & Ding, 2017), or whether that brand is related to their ideal self-concepts (Ward & Dahl, 2014), we examine consumer factors that affect reactions to brand rejection. That is, we demonstrate that the type of self-construal that is dominant for consumers (both at an individual level and a cultural level) can affect their reactions to luxury brand rejection. Our findings show consistently that interdependents are more likely than independents to retain a meaningful connection with a desirable but rejecting luxury brand. We also identify the underlying mechanism of the moderating effect of self-construal on consumer responses to luxury brand rejection by examining the mediating role of self-brand connections in this process. Our work extends understanding of the effect of self-brand connection in predicting the outcome of a negative consumer-brand interaction experience.

This research also has important managerial implications, and in particular, for cross-cultural customer relationship management. Luxury brands often use marketing tactics in order to deliver an exclusive brand image or to facilitate consumers' desire for the brand (Ward & Dahl, 2014), but these tactics can result in consumers feeling rejected by the brand. For example, it has been reported that the luxury fashion brand Lululemon hides all items that exceed two-digit sizes, preferring to not pander to plus-size clientele (Marks, 2013). Likewise, Yves Saint Laurent's tactic of training their employees to judge and filter customers based on what they are wearing, can feel exclusionary to customers (Thomas, 2018; Ward & Dahl, 2014).

While one might argue that luxury brands intentionally practice social exclusion in order to increase their brands' equity, our findings suggest that caution might be used in applying this strategy across cultures. Social exclusion does not necessarily enhance a luxury brand's image. Consumers in the United States, who tend to have a more independent self-construal orientation, may leave the brand in response to rejection. Luxury brand managers need caution in attending to consumer-brand relationships in those target markets that have a more independent client base. Instead of rejecting consumers outright and risking that consumers will defect to competitors, companies might stress in marketing communications alternative brand options, such as sub-branded memberships that are less exclusive but nevertheless maintain the exclusivity of the overall brand.

Alternatively, feelings of rejection by a luxury brand do not always discourage consumers. Chinese consumers, who tend to have a more interdependent self-construal orientation, may remain steadfast in keeping a favorable image of the brand despite feeling rejected by it. These findings, therefore, provide luxury brand marketers with insights on niche branding strategy design.

6.2 Limitations and future research

It is important to recognize several limitations of our research. First, we operationalize chronic self-construal with two different methods, that is, using Singelis (1994) scales and using cross-cultural differences, but using no manipulation of self-construal. While prior research sometimes employs experimentally induced priming approaches (Brewer & Gardner, 1996) to activate a more temporary self-construal, the present research results pertain to the important trait of self-construal and how it interacts with our experimental variables.

Additionally, since rejection occurs more commonly in luxury markets, we examine consumers' psychological and behavioral consequences following luxury brand rejection, yet it is not clear whether these effects would also emerge for mass-market brands. Comparing rejection effects for different types of brands could further shed light on consumer-brand relationships. Also, our research shows the moderating role of self-construal in response to luxury brand rejection, while not taking other relevant cultural factors into account, such as face-saving or power distance beliefs. For example, prior literature shows that as compared to the western market, luxury consumption in East Asia is related to face-saving, a critical Confucian value of one's public dignity and reputation (Le Monkhouse, Barnes, & Stephan, 2012). Additionally, research reveals that consumers respond differently to luxury brands depending on whether they have high power distance beliefs (i.e., accepting power disparities in a culture) or low power distance beliefs (not accepting of power disparities). In particular, consumers are more likely to purchase status products (e.g., luxury products) when their self-identity is threatened if they have higher (versus lower) power distance beliefs (Cui, Fam, Zhao, Xu, & Han, 2020). Future research might examine the possible confounding effects of these other cultural factors in the context of luxury brand rejection. Moreover, since consumers search for and learn more about luxury brand through online websites and social media, and increasingly purchase these brands online, it will be important to investigate how consumers respond to luxury brand rejection in different online scenarios. Finally, while we analyze short-term effects of brand rejection in the current research, future research might investigate the coping responses of consumers toward persistent luxury brand rejection.

Appendix A: STUDIES 1 AND 2: MANIPULATION OF BRAND REJECTION

Participants in both the control and rejected conditions were asked to imagine themselves in the following scenario:

Suppose that the luxury brand you selected has promoted a new kind of membership card recently, which can be used for purchasing special members-only products, participating in special events of the membership club, pre-purchasing limited editions of products, and other benefits. You and other consumers can apply for it on the official website of this luxury brand, and provide some basic personal information for their review. Once you are approved, you will receive a confirmation email and the membership card with a unique number. After that, you will become a member and can enjoy the services of this luxury brand!

In the control condition, participants were merely told about these benefits of the luxury brand's new membership card, and then moved on to the survey measures. In the rejected condition, participants read this additional text in which they were asked to imagine themselves receiving an email from the brand that refused their application:

Now imagine that you wanted to apply for it very much, so you provided your information and submitted your application on their official website successfully. However, you received an email from them soon after that, in which they rejected your application explicitly. However, someone else who applied at the same time as you, had already been approved and received the membership card of this brand.

Appendix B: STUDY 3: MANIPULATION OF BRAND REJECTION

Those qualifying for the rejection condition were given these instructions:

For the next few minutes, please recall and write about your recent experience of being rejected by a luxury brand you desired, including the luxury brand name, the place and the time it happened. It must be a time that you felt explicitly rejected in some way. For example, your application for their membership was denied, or you were restricted access to their products, or you felt that a salesperson showed rejecting attitudes toward you, etc.

Those qualifying for the inclusion condition were given these instructions:

For the next few minutes, please recall and write about your recent experience of successfully purchasing a desirable luxury brand, including the luxury brand name, the place, and the time it happened.

Biographies

Xian Liu is an Assistant Professor at the College of Tourism, Hunan Normal University. She received her PhD in Management from Antai College of Economics and Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. Her research interests include branding, consumer behavior, and tourism management. She has published in peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Product and Brand Management. Her research also appears in the Association for Consumer Research Conference and the European Marketing Academy Conference.

Barbara Loken is David C. McFarland Professor of Marketing at the Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota. She is an expert in the fields of branding and consumer psychology. She is also an honorary adjunct professor in the psychology department at the University of Minnesota. Her publications appear in premier journals of marketing, psychology, and health, including Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of Consumer Psychology, and The Lancet. She has served as Associate Editor for the Journal of Consumer Research and as editorial board member for the Journal of Consumer Research and Journal of Consumer Psychology.

Liangyan Wang is a Professor and the Chair of the Marketing Department at Antai College of Economics and Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Her research interests primarily relate to information processing, brand equity, brand crises, and decision-making. Her work appears in top journals including Strategic Management Journal, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Consumer Research, and Psychological Science.