Perceived Influences of Mentoring on Mentors' Social Well-Being: Social Self-Efficacy and Civic Engagement as Mediators of Long-Term Associations

ABSTRACT

In literature, there is a paucity of research examining the outcomes of mentoring programs for mentors. The goal of this study was to enhance understanding of the long-term impact of mentoring experiences on mentors' social well-being by testing a model in which the perceived influence of mentoring on work choices, volunteer choices and level of active participation in the community are associated with social self-efficacy, civic engagement (attitudes and behaviours), and, in turn, with social wellbeing. This study surveyed cohorts of former mentors (N = 203; 83% female) who took part in the mentoring and service-learning program called Mentor UP in Italy. Results showed the mediating role of social self-efficacy between the influence of mentoring on active participation in the community and social well-being (β = 0.05, p = 0.042) and between the same perceived influence of mentoring and civic engagement behaviour (β = 0.08, p = 0.009). Moreover, the influence of mentoring and social well-being was fully mediated by participants' current levels of civic engagement (attitudes and behaviours). These findings suggest that mentoring experiences can sustain college students' interpersonal effectiveness, civic responsibility and social well-being in long-lasting ways. Mentoring programs should therefore promote and measure these outcomes.

1 Introduction

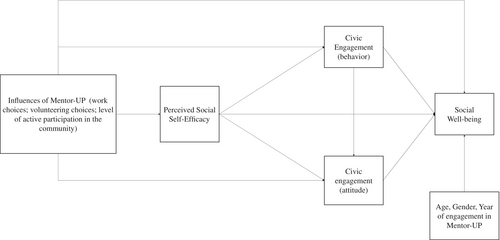

Mentoring aims to support the development of youth (called mentees) through the creation of a dyadic relationship with an experienced non-institutional adult figure called a mentor. Although most of the extant mentoring literature focuses on mentees' emotional and social positive outcomes (e.g., Claro and Perelmiter 2022), over the last decade a growing body of research has been paying attention to the influence of mentoring on mentors' well-being and civic engagement attitudes and behaviours (e.g., Weiler et al. 2013). The goal of this study is to add understanding to how the experience of being a mentor (in terms of perceived influence of mentoring on work choice, volunteer choice and active participation in the community) might influence perceived social self-efficacy and civic engagement, and how these developmental processes relate to longer-term social well-being (see Figure 1). The study builds on literature (e.g., Fenn et al. 2022) demonstrating that community involvement in its various forms (e.g., volunteering and service-learning, both elective and mandatory) is linked to increased self-efficacy, which drives future civic engagement. While motivations for different types of community participation may vary, they consistently offer experiences that foster work ethic, social skills and civic commitment (Haski-Leventhal et al. 2019). By contributing to the common good, youth develop critical skills like teamwork, expand their social networks, deepen their understanding of societal issues and enhance their overall well-being. Specifically, for the purposes of the current study, the experience of ex-mentors involved in an Italian mentoring and service-learning program (called Mentor UP) was examined.

1.1 Mentoring

In many countries, mentoring is a widespread approach to promoting youth development. In the United States, for example, growth in mentoring programs has occurred over more than half a century such that recent estimates are that around 1% of the adult population is involved as a volunteer mentor each year (Raposa, Dietz, and Rhodes 2017). Mentoring programs have also become increasingly widespread across other English-speaking countries and in continental Europe (Anderson and DuBois 2023; Preston, Prieto-Flores, and Rhodes 2019). Mentoring programs exist and have been studied (albeit less frequently) in Hong Kong, mainland China, South America, Sub-Saharan Africa and Israel, among others (Goldner and Mayseless 2009; Males, Ochoa, and Sorio 2017; Ng, Lai, and Chan 2014; Ssewamala et al. 2014). With support from philanthropies, non-governmental institutions and sometimes from governmental sources, mentoring programs are now found in many places as an established component of the ecosystems that support young people's learning and development (Akiva and Robinson 2022).

Alongside the proliferation of mentoring programs, decades of research have now been conducted on the effectiveness of mentoring as a strategy for promoting positive youth development and educational achievement among mentees. Helpful here are systematic reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., DuBois et al. 2011). For example, a meta-analysis by Claro and Perelmiter (2022) found evidence for small but consistent positive effects of mentoring on mentees' emotional well-being. A systematic review by Sánchez et al. (2018) that was focused specifically on Black male mentees found evidence for improved academic outcomes and positive effects on social–emotional well-being, mental health, interpersonal relationships and racial identity development. Likewise, a meta-analysis of 70 studies of the effects of mentoring by Raposa et al. (2019) found significant (but often small-to-moderate) positive effects across a range of academic, psychological, social and health outcomes.

Research on mentoring, however, has been heavily tilted toward programs in the United States, with few studies examining the effects of mentoring in other countries. This is a problem for many reasons, including the fact that historical factors that give rise to mentoring programs can vary widely across different countries. The (sub)populations that are the focus of mentoring often differ, as do the ways that mentoring is thought to contribute to local and societal goals. In Europe, mentoring has become most prevalent in countries with higher levels of immigration (Preston, Prieto-Flores, and Rhodes 2019), and especially in countries in the south such as Italy. In the United States, however, the focus is often native-born disadvantaged youth (Hagler et al. 2023) with relatively little attention given to the mentoring of immigrant youth (Oberoi 2016).

Across both contexts, mentoring can often involve an inherent paternalism and/or nativism in its orientation (Hagler et al. 2023; Preston, Prieto-Flores, and Rhodes 2019). Especially lacking are studies of mentoring in contexts outside of English-speaking countries or in southern Europe countries such as Italy. Italy presents an interesting context for studying the effects of mentoring, given its social conditions, such as the presence of youth with migration backgrounds and those at risk of poverty. The number of youth with immigrant backgrounds is particularly high in Italy representing 9.7% of the young people aged from 11 to 19 years as of January 2024 (Istat 2024a). Moreover, according to recent Istat data (2024b), 13.5% of minors under 16 years old were in specific material and social deprivation (with nearly three times higher deprivation among foreign children and adolescents—34.4%) in 2021 (Istat 2024b). In this context, youth mentoring is of special interest.

Despite unevenness in geographic coverage and potential differences in how mentoring fits into a given cultural or socioeconomic context, there is overwhelming consistency across the literature pointing to its potential for promoting positive youth development.

1.2 The Effects of Mentoring Programs on Mentors

Not surprisingly, an important commonality across the research literature is a singular focus on the influence of mentoring on mentees, despite theoretical frameworks positing reciprocity or mutual benefit in these relationships (e.g., Lester et al. 2019). When investigators do consider mentor-specific aspects (e.g., mentor personality characteristics), it is usually an effort to predict benefits of mentoring for mentees (e.g., Goldner and Mayseless 2009; McClain, Kelner, and Elledge 2021; Silke, Brady, and Dolan 2019). But mentors' experiences and well-being can potentially influence the mentoring relationship. For example, Marino et al. (2020) found that mentors' perceived support from an Italian mentoring program was associated with reduced reports of burnout, which in turn predicted higher quality mentoring relationships. Research on other forms of intergenerational community involvement has also found evidence that these relationships can benefit the supporting adults (Zeldin 2004; Zeldin, Christens, and Powers 2013). An emphasis on the bi-directional and mutually beneficial influences of mentoring has the added potential of countering unwanted and unintended aspects of paternalism or nativism that can undermine the goals of mentoring.

In addition to the literature highlighting the overall benefits of community participation (encompassing various forms of involvement; Fenn et al. 2022), over the last decade increasing scholarly attention is being directed toward the specific potential for mentoring to influence mentors. For instance, Weiler et al. (2013) found significantly higher levels of interpersonal and problem-solving skills, political awareness, self-efficacy related to community service and positive civic attitudes and behaviours for college students who mentored versus those who did not. Other researchers have examined the association between mentoring and mentors' civic and sociopolitical development (e.g., Nelson and Youngbull 2015; O'Shea et al. 2016; Simpson, Hsu, and Raposa 2023), but more common are studies focused on impacts involving mentors' academic achievement or social/relational development (Anderson and DuBois 2023). For example, multiple studies have revealed links between the experience of mentoring and mentors' subsequent reports of well-being (e.g., Anderson et al. 2023; Haber-Curran, Everman, and Martinez 2017; Peralta, Cinelli, and Bennie 2018; Tracey et al. 2014). Well-being, defined as the ability to reach personally relevant aims and to live a life of meaning (Greenwood et al. 2023), is receiving increased attention among health practitioners as a goal relevant to programs designed to promote active citizenship (Fenn et al. 2023; Petrillo et al. 2015). Social well-being, in particular, refers to individuals' evaluation of their public life and functioning in broader society (Keyes 2002). This construct represents a significant and suitable outcome when considering program effects on individuals' quality of life (Gothe et al. 2020), although little research has examined potential linkages between social well-being and mentoring.

We are only aware of one previous study that has examined the longer-term mediating effects of mentoring on mentors. Goldner and Golan (2017) conducted a study of 337 young Israeli adults (Mage = 30.06 years, SD = 9.33) 5–10 years after they participated in a college student mentoring program. Results indicated that mentors' ratings of the quality of their training as mentors was a significant positive predictor of their self-rated effectiveness as mentors, which in turn predicted current levels of civic attitudes and behaviour. Mentors who identified as female and Arab were more likely to view their mentoring as effective and Arab ethnicity was in turn associated with higher scores on a measure of civic attitudes and beliefs. These findings suggest that the effects of mentoring on mentors' civic attitudes and behaviours might resonate long into adulthood, and that variations in perceptions of the mentoring experience might be associated with longer-term trajectories of civic engagement and perceived civic self-efficacy.‘processes suggested as potentially important in mediating effects within existing research (e.g., enhanced sense of generativity) with the goals of developing greater insight into questions of “how” and “why” and building informative theories. For instance, it is possible that rewarding experiences when mentoring youth can help to instill confidence in interpersonal abilities that, in turn, promotes broader feelings of self-esteem or personal mastery’ (p. 1051).

1.3 Service-Learning to Facilitate Mentoring

Service-learning is a set of pedagogical strategies that integrate service in the community with structured learning proposals embedded within higher education courses, with the goal of educating civically engaged professionals (Compare and Albanesi 2022; Salam et al. 2019). Service-learning therefore has multiple goals that range from the pedagogical goals of the higher education programs, the goals of community actors that interact with the faculty members and students, and the goal of promoting more long-term civic engagement as cohorts of college students have influential experiences. For this last purpose, service-learning is often promoted as a promising approach for increasing levels of civic and community engagement among the broader public (e.g., Maya Jariego, Holgado Ramos, and Santolaya 2023). Service-learning shares much in common with other forms of volunteering, with the primary difference being that students are supported in their learning and development by faculty members and university staff who can facilitate their community engagement and complement it with on-campus training and discussions, including introducing critical perspectives that may not be present in other forms of volunteering (Mitchell 2015). Service-learning programmes can be implemented in highly differentiated ways, but over time, mentoring structured as a service-learning strategy is becoming increasingly popular (Schmidt, Marks, and Derrico 2004; Weiler et al. 2013) even though most mentoring programs are not offered as college-affiliated service-learning courses (Garringer, McQuillin, and McDaniel 2017). Mentoring programmes that are structured as service-learning can provide a support structure for college students to critically reflect as they develop knowledge and skills through their mentoring service.

1.4 Study Context: The Mentor UP Program

Mentor UP is a mentoring program of the University of Padova (Italy), offered as a service-learning course, in which university students serve as mentors for mentees who are at-risk pre-adolescents attending local primary to high schools (e.g., at risk of school dropout, social exclusion due to socio-economic disadvantages) or minors with immigrant background or driven out of their families and living in juvenile education centers. Mentor UP is structured as a service-learning program in which university students from different schools (who are pursuing degrees in a variety of disciplines) act as voluntary mentors in the city of Padova during their learning path, while offering their developing skills and knowledge to the community. It should be noted that service-learning courses are not compulsory in Italy. At the University of Padova, students can choose this mentoring and service-learning course from a wide range of electives. If they decide to participate in the course, they have the option to choose whether to volunteer in the community and be supervised.

Mentors are enrolled at the beginning of each academic year; they are trained for 12–20 h of classes (about the practices of mentoring and service-learning, how to build and maintain a relationship, communication skills, non-violent principles and communication, multicultural skills, volunteering and about cultural and recreational opportunities in the local community) following principles of community psychology (e.g., empowerment, prevention and well-being promotion and connection to the community); then, mentors are paired with mentees and are supervised every 3 weeks in small groups by the program staff. The supervisory group meetings are one the most important service-learning activities of Mentor UP because students have the opportunity to critically reflect on their experiences, to share thoughts and challenges of serving the community with other students and faculty members, to learn how to offer/receive assistance in resolving relationship issues and deal with potential problems with mentees or the institutions. These regular meetings also ensure consistent mentor attendance and increase students' knowledge of context characteristics and challenges as well as their self-awareness and satisfaction as mentors (Marino et al. 2020). Mentor UP is a mixed school- and community-based program because pairs meet once a week for at least 2 h (from November to June) either at school (especially at the beginning of the program) or around the city, promoting connection to the neighbourhood and to the city facilities and resources. In this view, Mentor UP connects and combines the needs of the city with the immense resources represented by the large number of university students living in the city motivated to contribute meaningfully to the community during their higher education path. As an example, a previous analysis of the motivations to volunteer in the context of Mentor UP revealed that mentors were primarily motivated to expand their knowledge and express their values through service-learning, however they reported the greatest gains in knowledge and career development at the end of the program (Bergamin et al. 2020). More details about the Mentor UP program can be found elsewhere (Marino et al. 2020, 2021, 2022).

1.5 Current Study: Aims and Hypothesis

In this study, we sought to expand understanding of mentoring and its possible influences on mentors by examining the associations between mentors' perceptions of the influence mentoring had on their lives (in terms of work choices, volunteer choices and active participation in the community), social self-efficacy, civic engagement and social well-being. Specifically, the aim of the study was to test whether mentors' perceived influence of their mentoring experience was associated with social well-being both directly and indirectly via social self-efficacy and civic engagement (attitudes and behaviour) in a sample of young adults who had previously been involved in a university-affiliated mentoring program in Italy called Mentor UP (Figure 1).

To our knowledge, there is a lack of studies that have examined direct associations between the influence of mentoring on mentors' lives and social well-being. For this reason, the first hypothesis (hp1) of the current study is that the mentors' perceived influences of mentoring (on work choices, volunteer choices and active participation in the community) would be positively associated with their social well-being, in line with the literature briefly reviewed above suggesting that positive experiences gained from mentoring young people can help build confidence in social skills, which fosters a greater sense of self-worth and social achievement (Anderson and DuBois 2023).

With regards to social self-efficacy, existing research suggests communication and other relational skills are fostered through mentoring relationships (Mboka 2018; Wasburn-Moses, Fry, and Sanders 2014) and that self-efficacy is often enhanced among mentors (Bailey 2021; Elliott, Mavriplis, and Anis 2020; Weiler et al. 2013). Indeed, some previous studies have found that mentoring can promote self-efficacy (e.g., Ayoobzadeh and Boies 2020) and possibly mediates the relationship between well-being and voluntary civic engagement (e.g., Brown, Hoye, and Nicholson 2012). We therefore posited social self-efficacy as a mediator of the association between mentoring influences and social well-being (hp2a) and between mentoring influences and civic engagement (hp2b) (hypothesizing positive relationships among all three of these measures; hp2).

Given previous research suggesting that involvement in service-learning and in mentoring can promote civic engagement and civic development (e.g., Compare and Albanesi 2022; Ilić, Brozmanová Gregorová, and Rusu 2021; Simpson, Hsu, and Raposa 2023), we also hypothesized that participants who reported greater influence from mentoring would report higher levels of current civic engagement (attitudes and behaviour), both directly (hp3), and that civic engagement would mediate the relation between mentoring influence and social well-being (hp4) (see Figure 1). Indeed, evidence from a variety of contexts suggests that volunteering and civic engagement can promote social well-being (Albanesi, Cicognani, and Zani 2007; Chan and Mak 2020; Chan et al. 2021; Lühr, Pavlova, and Luhmann 2022). Finally, we specified the direction of the path from civic behaviours to attitudes (hp5; Christens, Peterson, and Speer 2011)—rather than the reverse as in many other previous studies (e.g., Goldner and Golan 2017).

2 Methodology

2.1 Participants

Participating in this study were 209 former mentors from a university-affiliated mentoring program called Mentor UP. Of these 209, six were excluded from data analysis due to missing data on key constructs. Thus, the final analytic sample comprised 203 mentors (83% females, M = 26.1 years, SD = 4.2, range 20–52 years). Most (62%) had taken part in Mentor UP between 2016 and 2020 and were from the school of psychology (90%). About half of the sample was still enrolled at university (50%), whereas the other half had a master's degree. 43% declared themselves to be employed. Nearly all (186, 91.7%) had participated in Mentor UP for one academic year whereas the remaining participants (n = 17) had participated for 2 or 3 academic years. Mentors were mostly volunteers, although about 11% had also earned academic credit for mentoring.

2.2 Procedure

The present study used a retrospective design that included both validated questionnaires (see Measures section) as well as items specifically developed for the present study (see Appendix A) in line with the procedure used by Goldner and Golan (2017). This approach was chosen following other mentoring retrospective studies (e.g., Rodriguez et al. 2021), in which former mentors were contacted after their mentoring experiences. In the context of Mentor UP, this quantitative approach was pursued (instead of a qualitative study design) only for time and opportunity reasons, that is to increase the probability that former mentors would agree to complete a short online questionnaire more readily than agreeing to take part in a time-consuming interview. In March 2021, a subset of 499 ex-mentors who had been involved in the program from 2011 to 2020, and for whom contact information was available, were invited via email and social media to complete an online survey about their experiences with Mentor UP, which meant their formal role as a mentor had ended one to 10 years before participating in the current study. Because of inactive/old email addresses, several attempts were made to contact all 499 ex-mentors, which resulted in 42% of ex-mentors completing the online survey. Participants first gave formal consent and then completed the survey in approximately 20 min. The study was approved by the local Ethic Committee for Psychological Research (protocol number: 4043) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Social Well-Being

Social well-being was assessed with the 5-item subscale of the Italian version of the Mental Health Continuum–Short Form (MHC–SF; Petrillo et al. 2015; original English version: Keyes 2009). Participants were asked to rate how often they feel in a specific manner (sample item ‘How often did you feel that you had something important to contribute to society’). The 5 items were rated on a 6-point scale from 1 ‘never’ to 6 ‘every day’. The Cronbach's alpha in the current sample was 0.78 (0.73–0.82).

2.3.2 Civic Engagement (Attitude and Behaviour)

Civic engagement attitudes and behaviours were assessed with the Italian version of the Civic Engagement Scale (Procentese, De Carlo, and Gatti 2019; original English version by Doolittle and Faul 2013). The scale includes two subscales: the attitude subscale (8 items rated on a 7-point scale from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’; sample item ‘I am committed to serve in my community’) and the behaviour subscale (6 items rated on a 7-point scale from 1 ‘never’ to 7 ‘always’; sample item ‘I am involved in structured volunteer position(s) in the community’). The Cronbach's alphas in the current sample were 0.83 (0.80–0.87) for the attitude subscale and 0.84 (0.81–0.87) for the behaviour subscale.

2.3.3 Perceived Social Self-Efficacy

Perceived social self-efficacy was assessed using the Perceived Social Self-Efficacy Scale (original Italian version: Caprara 2001). Participants were asked to rate their beliefs about their ability to feel comfortable in social interactions and play a proactive role in social situations (e.g., ‘How able are you to express your opinion to a group of people that is discussing a topic you are interested in?’). The scale has 15 items rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not able at all; 5 = fully able). Cronbach's alpha for this scale for the current sample was 0.90 (0.88–0.92).

2.3.4 Perceived Influence of Mentoring

Former mentors were asked to rate the degree to which Mentor UP influenced three key domains in their life: (a) work choices, (b) volunteer choices and (c) level of active participation in the community. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all; 5 = very much). The three items were developed ad hoc for the purpose of the current study (see Appendix A), due to the lack of extant validated measures assessing perceptions of the influence of mentoring on life choices and active citizenship among former mentors. Indeed, previous studies have also used ad hoc measures to assess the degree to which mentoring or service-learning influenced students' active citizenship (e.g., in terms of civic engagement, social responsibility and citizenship skills), as well as various ‘soft’ skills such as working with diverse groups, oral and written communication, critical thinking and practical problem solving (e.g., Holland 2001; Mackenzie, Hinchey, and Cornforth 2019; Sabo et al. 2015; Taylor and Leffers 2016).

2.4 Analytic Approach

All analyses were performed using R (R Core Team 2024). We first computed descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables (see Table 1). We then used path analysis using the lavaan package (Rosseel 2012) to test the hypothesized model employing a single observed score for each construct included (Figure 1). A bootstrapping procedure with 5000 samples was used to test the presence and size of the expected mediations (Hayes 2022). In the tested model, the three domains of mentoring influence (work choices, volunteer choices and level of active participation in the community) were expected to be positively associated with social self-efficacy, both dimensions of civic engagement and social well-being. Similarly, we anticipated that social self-efficacy would be linked to both dimensions of civic engagement and social well-being. Simultaneously, civic engagement behaviour was expected to be related to civic engagement attitudes and social well-being. Finally, civic engagement attitudes were expected to be linked to social well-being. Age, gender and year of engagement in Mentor UP were imputed as covariates.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social well-being | — | ||||||||

| 2. Civic engagement—Attitude | 0.36*** | — | |||||||

| 3. Civic engagement—Behaviour | 0.41*** | 0.53*** | — | ||||||

| 4. Perceived social self-efficacy | 0.40*** | 0.32*** | 0.43*** | — | |||||

| 5. Influence of Mentor UP on work choices | 0.15* | 0.17* | 0.28*** | −0.00 | — | ||||

| 6. Influence of Mentor UP on volunteer choices | 0.06 | 0.30*** | 0.29*** | 0.10 | 0.42*** | — | |||

| 7. Influence of Mentor UP on active participation in the community | 0.19** | 0.29*** | 0.37*** | 0.22** | 0.33*** | 0.57*** | — | ||

| 8. Year of engagement in Mentor UP | −0.15* | −0.01 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.03 | — | |

| 9. Age | 0.15* | 0.04 | 0.18** | 0.19** | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.59*** | — |

| 10. Gender | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 |

| M | 3.03 | 5.34 | 3.75 | 3.39 | 2.66 | 2.59 | 2.64 | 6.29 | 26.13 |

| SD | 0.93 | 0.78 | 1.30 | 0.60 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 2.27 | 4.18 |

| Range | 1–6 | 2.38–7 | 1–6.83 | 1.87–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–9 | 20–52 |

- Note: N = 203.

- Abbreviations: M = Mean, SD = standard deviation.

- *** p < 0.001.

- ** p < 0.01.

- * p < 0.05.

To evaluate overall model fit, several indices were used: the comparative fit index (CFI), whose value can range from 0 to 1 fit and where values higher than 0.95 are suggested for a good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999); the standardised root mean square residuals (SRMR), for which values lower than 0.08 are recommended (Hu and Bentler 1999); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), for which values lower than 0.06 are advised (Hu and Bentler 1999); and the Total Coefficient of Determination (TCD), which measures the overall proportion of variance explained by the model (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1996). Because of the relatively small number of participants, it was essential to reach the most parsimonious model, thus, to calculate the least number of coefficients. To do so, non-significant links were deleted using a stepwise method (Lenzi et al. 2015; Marino et al. 2016). After each removal, old and new models' goodness of fit were assessed using the log-likelihood ratio test, for which significant values determine whether the two models significantly differed in their abilities to fit the data. If the models' fit did not differ, the more parsimonious one was used. All intermediate models, as well as all log-likelihood ratio tests, are available in Appendix S2.

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations and correlations among study variables are displayed in Table 1. Significant positive correlations were found among the three domains of mentoring influence: active participation in the community and work choices (r = 0.33, p < 0.001), active participation in the community and volunteer choices (r = 0.57, p < 0.001) and work choices and volunteer choices (r = 0.42, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

| Independent variable | Mediators | Outcome: Social well-being | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influence of Mentor UP on work choices | β | 95% CI | z | p | |

| CE—Behaviour | 0.044 | 0.000–0.087 | 1.956 | 0.051 | |

| CE—Behaviour CE—Attitude | 0.018 | 0.000–0.037 | 1.922 | 0.055 | |

| Influence of Mentor UP on volunteer choices | |||||

| CE—Attitude | 0.028 | −0.004–0.060 | 1.699 | 0.089 | |

| Influence of Mentor UP on active participation in the community | |||||

| Perceived social self-efficacy | 0.053 | 0.002–0.105 | 2.045 | 0.042 | |

| Perceived social self-efficacy CE—Behaviour | 0.017 | −0.001–0.036 | 1.828 | 0.070 | |

| Perceived social self-efficacy CE—Behaviour CE—Attitude | 0.007 | −0.001–0.015 | 1.811 | 0.070 | |

| CE—Behaviour | 0.079 | 0.015–0.144 | 2.417 | 0.016 | |

| CE—Behaviour CE—Attitude | 0.033 | 0.004–0.062 | 2.262 | 0.024 | |

| CE—Behaviour | |||||

| Influence of Mentor UP on active participation in the community | β | 95% CI | z | p | |

| Perceived Social Self-efficacy | 0.083 | 0.021–0.145 | 2.625 | 0.009 | |

| CE—Attitude | |||||

| Influence of Mentor UP on active participation in the community | β | 95% CI | z | p | |

| Perceived social self-efficacy CE—Behaviour | 0.041 | 0.009–0.073 | 2.490 | 0.013 | |

- Note: N = 203.

- Abbreviations: CE = civic engagement, CI = confidence interval.

Social well-being was positively associated with both civic engagement dimensions (r = 0.36, p < 0.001 for attitude and r = 0.41, p < 0.001 for behaviour), with perceived social self-efficacy (r = 0.40, p < 0.001), and with two of the three domains of mentoring influence, specifically work choices (r = 0.15, p = 0.033) and level of active participation in the community (r = 0.19, p = 0.007). The association with volunteer choices was not significant (r = 0.06, p = 0.383). As expected, the two civic engagement measures were significantly correlated with each other (r = 0.53, p < 0.001) and with social self-efficacy (r = 0.32, p < 0.001 for civic engagement attitude; r = 0.43, p < 0.001 for civic engagement behaviour) and with all three domains of mentoring influence. Specifically, civic engagement attitudes were related to the mentoring influence domains of active participation in the community (r = 0.29, p < 0.001), work choices (r = 0.17, p = 0.015) and volunteer choices (r = 0.30, p < 0.001); civic engagement behaviour scores were significantly associated with the mentoring influence domains of active participation in the community (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), work choices (r = 0.28, p = 0.015) and on volunteer choices (r = 0.29, p < 0.001). Finally, social self-efficacy was positively linked to the mentoring influence domain of active participation in the community (r = 0.22, p = 0.002), but not to work choices (r = −0.004, p = 0.957), or to volunteer choices (r = 0.10, p = 0.177).

3.2 Path Analyses

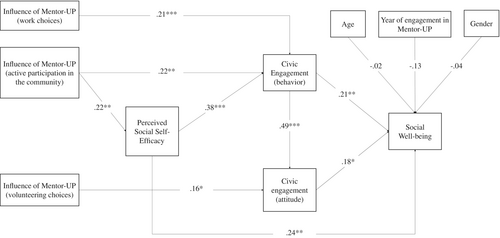

The first model showed a good fit to the data (CFI = 0.967, RMSEA = 0.063, SRMR = 0.044 and TCD = 0.26); nonetheless numerous non-significant associations were present (including the direct associations between the three influences of Mentor UP and social well-being, which did not support hp1; see Appendix B). Thus, four new models were evaluated in a stepwise fashion (Appendix B). The final model fit the data well (CFI = 0.960, RMSEA = 0.049, SRMR = 0.049 and TCD = 0.23), revealing a non-significant log-likelihood ratio test compared to the first model (χ2 = 10.5, df = −9, p = 0.311), and all estimated coefficients were statistically significant at the 5% level, apart from the covariates. Path coefficients for the final model are presented in Figure 2.

A complex pattern of associations emerged from the final path analysis (Table 2). Social self-efficacy was a mediator between the influence of mentoring on active participation in the community and social well-being (β = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.002–0.105, p = 0.042), partially supporting hp2a. Moreover, social self-efficacy was a mediator between the influence of mentoring on active participation in the community and civic engagement behaviour (β = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.02–0.14, p = 0.009), partially supporting hp2b. Further sustaining hp2b, we found a serial mediation via social self-efficacy and civic engagement behaviour, linking the influence of mentoring on active participation in the community and civic engagement attitudes (β = 0.04, 95% CI = 0.01–0.07, p = 0.013). The three influences of mentoring displayed different direct associations with civic engagement, partially confirming hp3. Specifically, the influences of mentoring on work choice and on active participation in the community were both associated with civic engagement behaviour (respectively β = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.09–0.32, p = < 0.001 and β = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.09–0.36, p = 0.001), while the influence of mentoring on volunteering choices was associated with civic engagement attitudes (β = 0.16, 95% CI = 0.02–0.29, p = 0.024). Additionally, we found two significant indirect associations between the influence of mentoring on active participation in the community and social well-being via the two civic engagement dimensions, partially supporting hp4. More specifically, we determined a single mediating effect of civic engagement behaviour (β = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.02–0.14, p = 0.021), and a serial mediating effect via civic engagement behaviour and attitudes (β = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.00–0.06, p = 0.030). Finally, civic engagement behaviour was significantly associated with civic engagement attitudes (β = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.39–0.59, p < 0.001) sustaining hp5. Covariates (i.e., age, gender and year of engagement in Mentor UP) were not associated with social well-being in the path analyses (see Figure 2), suggesting that a comparable outcome might be observed for mentors with different characteristics.

R2 statistics were good for all constructs, apart from perceived social self-efficacy: social well-being (R2 = 0.25), civic engagement's attitudes (R2 = 0.30) and behaviours (R2 = 0.31), and social self-efficacy (R2 = 0.05). Furthermore, the TCD of the model was 0.23 (corresponding to a correlation of 0.48), which is a medium-large effect size (Cohen 1988).

4 Discussion

The goal of this study was to add to understanding of how the experience of mentoring could influence mentors' social and civic developmental trajectories, and how these developmental processes relate to longer-term social well-being. Social well-being—an evaluation of one's own public life and functioning in society (Keyes 2002)—is a useful criterion for judging benefits for mentors given its positive association with quality-of-life indices (Gothe et al. 2020). Bivariate correlations partially supported the first hypothesis (hp1) that participants' ratings of the influence of mentoring on their lives was significantly and positively associated with social well-being post-mentoring, with the exception of the influence of Mentor UP on volunteer choices. However, results of the path analysis did not sustain the direct effects of the influences of Mentor UP on social well-being but showed a complex pattern of associations among the study variables and highlighted the mediating role of social self-efficacy and civic engagement that, taken together, provides new insights about the potential mechanisms that could be driving the sustained effect of mentoring and other community-involved service-learning opportunities.

In line with findings reported by Goldner and Golan (2017), the perceptions of former mentors about the influence mentoring had on their life was related to current attitudes, behaviours and self-perceptions in distinct ways. Sustaining hp2a, social self-efficacy was a positive mediator in the association between the influence of Mentor UP on participation in community activities and social well-being. This result may indicate that skills enhanced during mentoring and service-learning experiences (such as the ability to use assertive communication with mentees or during a social interaction with agents from local institutions) might increase social well-being, for example in terms of increased perception of social integration and acceptance (Petrillo et al. 2015). Moreover, social self-efficacy also mediated the link between the influence of mentoring on participation in community activities and current levels of civic-engaged behaviour, sustaining hp2b (e.g., Manganelli, Lucidi, and Alivernini 2015). Thus, it is possible that Mentor UP offered college students a context for participating in local activities (where social contacts are based largely on geographical proximity) that helped them acquire and strengthen skills needed to interact with individuals from diverse backgrounds, thereby nurturing their social self-efficacy. For example, mentors participating in Mentor UP were mostly involved in multicultural mentoring relationships with their mentees and it is likely that they might have developed new social skills to be used in current civic-engaged behaviours, as they might have learnt how to deal with the specificity of a multicultural context, such as the city of Padova, in which foreign citizens represent more than 10% of the population. Indeed, such perceptions that mentoring influenced mentors' participation in community activities and their work choices were both significantly linked to higher levels of civic engaged behaviour, whereas the influence of mentoring on volunteer choices was significantly associated with civic engagement attitudes (sustaining hp3). Taken together, these findings suggest mentoring (and possibly other community-involved service-learning experiences) can shape college students' career and volunteering decisions, orienting them toward paths in which community involvement and active participation are key elements (e.g., Bergamin et al. 2020) that possibly result in increased social well-being (hp4). Coherently, we also found evidence that the association between the influence of mentoring and social well-being was fully mediated by participants' current levels of civic engagement—both attitudes and behaviours (hp4).

Finally, we also find support for hp5 that defined the direction of the association between civic engagement behaviour and attitudes, based on research on community participation and psychological empowerment suggesting that socialisation from community participation can exert influence on subsequent attitudinal changes (Christens, Peterson, and Speer 2011). Viewed as a whole, these findings align with previous work (e.g., Astin et al. 2000) indicating service-learning experiences can have sustained positive effects on college students' interpersonal effectiveness and civic responsibility that, in turn, can enhance students' sense of belonging and perception to be able to contributing to society. Mentoring should be understood not only as a support for mentees' positive development, but also as a form of volunteer activity that is also likely to contribute to mentors' positive development through influences on their longer-term civic developmental trajectories (Flanagan and Christens 2011).

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

Our study had several strengths, most notably being one of only two studies to examine potential long-term benefits of mentoring for mentors (Goldner and Golan 2017). Also noteworthy is that our study, unlike most research on youth mentoring, examined a mentoring program that operates outside of the United States, focusing on the analysis of a local mentoring program characterised by service-learning structure and close contact with the local community. Exogenous variables tested in our study captured variation in the extent to which mentors perceived the experience of mentoring as impactful across different domains of life (i.e., work choices, volunteer choices and active participation in their local community), and the perceived influence of mentoring across these domains helped explain variance in their subsequent civic and psychosocial development. Our findings also provide important insights into longer-term civic and psychosocial developmental processes likely unfolding among former mentors. We found both direct and indirect effects from the perceived influence of mentoring to social well-being, thereby adding substantially to our understanding of the processes that are likely to unfold when college students are engaged in a mentoring relationship (Anderson and DuBois 2023). However, it should be noted that the results of this study might be, at least partially, influenced by the specificity of the Mentor UP program because it is a mentoring program but applies the service-learning reflection structures and implies a close contact with the community partners (such as schools and educational juvenile centers), that might not be as implemented in traditional mentoring programs.

Our study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the current findings. Our sample of former mentors was relatively small, and most were women (even though a percentage of 90% women is usual in Mentor UP), which limits the potential to generalise our findings to more diverse groups of mentors. Moreover, due to the size of our sample, we could not test invariances across age, gender and year of engagement in the program, further limiting the data interpretation. A further specificity of our sample is that 50% of the participants were still university students at the time of the study. This sample characteristic may potentially influence the understanding of the results because, for example, university students might be still in the process of developing attitudes and behaviours related to civic engagement as compared to employed participants who might be more likely to currently experience satisfaction for their contribution to society. Our data were also based entirely on participants' self-reports, including items created to assess perceptions of the influence mentoring had on mentors' lives.

Beyond quantitative data, future studies in the field should adopt mixed-method designs (e.g., including interviews). This could uncover more detailed information about ex-mentors' experiences and individual perspectives about the benefits of mentoring and service-learning. In light of the acknowledged limitations of retrospective surveys with respect to data validity and reliability—including memory distortion, variability in personal perceptions, contextual factors and response bias—we thus propose that future studies qualitatively investigate the meditational relationships that were identified in this study. This approach could enhance the field's understanding by providing nuanced insights and contextualising participants' experiences, including insights into individual differences. Finally, the cross-sectional design of our study did not allow for causal inference, although findings from path analyses are suggestive of potential underlying mechanisms that could be tested in longitudinal research. Missing from the current study were several important variables that could further elucidate the impacts of mentoring on mentors. Future studies should consider assessing the quality of the relationship between mentors and mentees (assessed both at the time of participation in the program and currently). This information can help to explain the extent to which the reciprocal relationship is the key factor that increases the perceived influence in mentors' current life. Moreover, it would be useful to assess mentors' baseline levels of civic engagement, social self-efficacy and social well-being in order to observe actual changes over time in these dimensions. Also worth examining are aspects of mentoring viewed as most important, such as the quality of training received, the role of supervisory meetings, the opportunity to follow a structured volunteering experience or the experience of engaging with different cultures.

4.2 Implications

Findings from this study can inform future efforts to examine the complex influences that relational interventions such as mentoring can have on the further development of participants' social responsibility and psychosocial adjustment. As expected, many of the participants in our study viewed mentoring as influential in shaping their life trajectories across multiple domains, including civic engagement and social self-efficacy (O'Shea et al. 2016). In fact, these associations were so strong that they fully mediated the association between the influence of mentoring and social well-being. Indeed, social self-efficacy appears to play a key mediating role. Like social well-being, social self-efficacy is a domain-specific indicator that seems well-suited to assessing the effects of relational interventions, especially in comparison to global indicators of self-efficacy (e.g., Çankaya, Dong, and Liew 2017).

In line with earlier studies exploring the role of community service self-efficacy on well-being (Fenn et al. 2021; Harp, Scherer, and Allen 2017), we found that social self-efficacy was strongly associated with civic-engaged behaviour and had a direct association with social well-being. Social self-efficacy could therefore be considered a nearer-term (proximal) indicator for the effective engagement of mentors. Program evaluators who are unable to follow mentors over long periods of time might consider social self-efficacy as a nearer-term indicator that is likely to be linked over time with higher civic engagement and positive well-being. Other forms of service-learning programs, for instance, could assess social self-efficacy. Among the broader range of service-learning approaches, however, mentoring may be especially likely to promote gains in social self-efficacy due to the fact that it is an inherently relational form of service-learning.

We examined civic-engaged behaviour and attitudes as separate constructs, which was helpful in revealing potentially important insights into developmental processes that involve civic and social responsibility. Social self-efficacy was associated with greater levels of civic-engaged behaviour but not with civic-engaged attitudes. Drawing from research on psychological empowerment (Christens, Peterson, and Speer 2011), we expected to find a significant path from civic engagement behaviour to attitudes rather than the reverse (attitudes influencing behaviours). This contrasts with many theoretical models (e.g., the theory of planned behaviour) that position behaviour as an outcome of attitudes and motivations, including in studies of the effects on mentors (e.g., Goldner and Golan 2017). Although there is clearly bi-directional influence between civic attitudes and behaviours, this study found support for the ‘socialisation mechanism’ (Christens, Peterson, and Speer 2011, 340) that has been studied in psychological empowerment processes, and that should also be examined in ongoing studies of civic development processes and the influence of mentoring experiences.

Our findings also have implications for the practice of mentoring. Participation in mentoring, as a service-learning strategy, is likely to be beneficial for both mentors and mentees and could shape the trajectory of mentors' social well-being and civic responsibility in long-lasting ways. From a policy and practice perspective, therefore, mentoring should not be viewed as a unidirectional intervention meant to benefit mentees only; rather, the expected outcomes should be viewed as reciprocal. Some mentors will be more affected by their mentoring experience than others, but the current findings argue that those who perceive mentoring as having had an influence are likely to have enduring gains in social self-efficacy, be more civically engaged, and report greater levels of social well-being. Therefore, evaluations of formal mentoring programs should routinely assess these potential processes and outcomes.

4.3 Conclusion

Our study addressed at least four major gaps or imbalances in what is currently understood about the impact of mentoring programs. First, most research has focused exclusively on the benefits to mentees, thereby ignoring the possibility of mutually beneficial influences and also reinforcing inadvertently paternalistic and nativist views about the purposes of mentoring and its intended effects. Second, our study adds to the growing body of work on mentoring programs outside the United States and other English-speaking countries. Third, our effort to examine the influence of mentoring is one of only two studies that examined these processes over a period of years, versus weeks or months. Fourth, this study tested meditational pathways across social and civic developmental processes and outcomes, which offer new insights into how and why mentors' experiences can be influential (Anderson and DuBois 2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Chiara Bonechi for helping with the data collection. Open access publishing facilitated by Universita degli Studi di Padova, as part of the Wiley - CRUI-CARE agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.