Ischemic colitis following left antegrade sclerotherapy for idiopathic varicocele

Abstract

The Tauber procedure, i.e., antegrade sclerotherapy for varicocele, can lead to ischemic colitis. The pathogenesis can involve an atypical systemic-portal communication, which could represent an infrequently reported (rare) anatomical variant. The aim of this study is to review clinical cases from the literature to highlight the anatomical bases of such complications. A computer-aided and hand-checked review of the literature was used to identify relevant publications. Also, the computed tomography (CT) examination of a clinical case with medico-legal implications due to severe vascular complication following Tauber's procedure was reviewed. Although specific references to this complication have appeared since the 19th century, reports in the contemporary literature include only a few clinical cases of ischemic colitis following Tauber's procedure. The CT scan images of a filed lawsuit revealed traces suggesting a significant communication between the testicular and left colic veins, forming part of the systemic-portal anastomoses. An anatomical variation consisting of a communication between the testicular and left colic veins has been described from the clinical point of view, corresponding to a significant anatomical finding identified in the past that has been under-reported and its clinical importance subsequently underestimated. For the first time we have demonstrated its pathophysiological significance in a real clinical scenario, linking the anatomical variation to the clinical complication. This demonstrates the importance of raising scientific awareness on this issue to prevent possibly devastating complications in daily clinical practice. Clin. Anat. 31:774–781, 2018. © 2018 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Forensic clinical anatomy is a new applied branch of clinical anatomy intended to elucidate and evaluate medico-legal issues, in which individual anatomy (normal anatomy, anatomical variations, age, disease, or surgery-related changes) can acquire significance (Porzionato et al., 2017). Forensic clinical anatomy can be defined as “the practical application of anatomical knowledge and methods (from ultrastructural to macroscopic aspects), endowed with substantial clinical/surgical implications, for ascertaining and evaluating medico-legal problems” (Porzionato et al., 2017). In a forensic clinical setting with relevant anatomical bases, the significance of anatomy becomes clear owing to its possible judicial implications.

When individual anatomy is considered, congenital anatomical variations/anomalies need to be included, together with age-related changes (development, maturation, and aging), diseases, surgical procedures, or postmortem modifications, the latter concerning differences between living and cadaveric anatomy. Legal medicine, for which forensic clinical anatomy is potentially very important, is the sub-discipline devoted to managing so-called medical malpractice in which judicial liability is suspected (Porzionato et al., 2017).

On this point, a clinical case of severe vascular complication following left antegrade sclerotherapy for idiopathic varicocele (Tauber's procedure) was reviewed. It had been published by the physicians who assisted during the patient's hospitalization as a urological case. The focus was on the clinical management of this rare adverse event, without deeper inspection of the radiological images for morphological features that could have revealed an anatomical variant potentially explaining the complication (Fulcoli et al., 2013).

From an anatomical point of view, the left gonadal and suprarenal veins drain into the left renal vein, which crosses under the superior mesenteric artery to reach the inferior vena cava. There are few reports of significant anatomical variations of the testicular venous drainage or of this type of systemic-portal communication. Nevertheless, atypical vascular communications between the testicular vein (general venous system) and the left colic vein (hepatic portal system) were proposed as a pathophysiological explanation of the clinical picture.

The aim of this article is to review clinical cases from the literature to highlight the significance of the anatomical bases of such complications, possibly revealing a novel type of systemic-portal communication in addition to the most frequently reported forms and the traditionally taught anatomy, with observations about its contemporary clinical relevance and possible medico-legal implications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In February 2017, we performed a computer-aided systematic review of the literature by searching MEDLINE/PUBMED, EBSCO, WEB OF SCIENCE, and SCOPUS as previously described (Boscolo-Berto et al., 2014), to identify publications concerning anastomoses between the testicular and visceral veins. To avoid missing studies, broad search terms were used with no temporal limits or language restrictions.

The MEDLINE/PUBMED, EBSCO, and SCOPUS searches employed a complex inquiry strategy including “free-text” protocols into the full-text. More specifically, a multiple unrestricted “free-text” search was performed combining the terms ((“spermatic vein” OR “testicular vein”) AND “anastomosis).” Because of the interface limitation, the search fields for WEB OF SCIENCE were “topic OR title.” To search further potentially relevant papers, references from the included studies and treatises held in our departmental library were hand-checked for pertinent information.

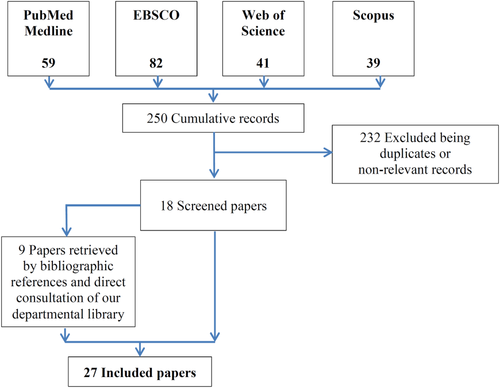

Also, Computed Tomography (CT) examination of a clinical case (Fulcoli et al., 2013) was retrieved. The CT scans of this case were performed on a Light Speed VCT (General Electric) with slice thickness 2.5 mm and were analyzed and postprocessed on an Aquarius Workstation. The 2D axial, coronal and sagittal sections, the maximum intensity projection, volume rendering technique, and multiplanar reconstruction were all analyzed.

RESULTS

The combined search with free-text protocols in the MEDLINE/PUBMED, EBSCO, WEB OF SCIENCE, and SCOPUS databases retrieved 59, 82, 41, and 68 records respectively. After the duplicates had been removed and the nonrelevant records excluded we selected 18 papers. Nine more publications retrieved from the references and from consultation of our departmental library were also included (Fig. 1).

Systematic search process. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Overall, we found four clinical cases reporting an ischemic complication of the colonic tract following Tauber's procedure (Table 1).

| Paper | Age (years) | Diagnosis at presentation | Intra-operative phlebography | Clinical presentation | Delay vs procedure | Imaging | Pathological findings | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iaccarino et al. | NR | NR | Unclear (Probably no) | NR | NR | NR | Devastating sigmoid i nfarction | NR | NR |

| Spiezia et al. | 21 | Varicocele (III) with Oligoasthenospermia and infertility | Unclear (Probably no) | Pain in the lower abdominal quadrants | NR (“Early”) |

Abdominal-Rx CT scan |

Colic wall with coagulation necrosis, hemorrhagic transparietal extravasations with thrombosis of some vessels and widespread active chronic inflammatory infiltrate | Hartmann's resection with temporary colostomy | Not relevant |

| Fever (37.8°C) | |||||||||

| Vicini et al. | 35 | Varicocele (III) with Oligoasthenospermia and infertility | Yes | Pain in the left iliac fossa and flank | Immediate after sclerosant injection |

CT scan Rectoscopy |

NR | Colic resection with temporary colostomy | Not relevant |

| Fulcoli et al. | 34 | Varicocele (IV) with Oligoasthenospermia and infertility | Yes | Pain in the abdomen and inguino-scrotal region | Half an hour |

CT scan Colonscopy |

Massive venous thrombosis of the mucosa and submucosa of the resected colon | Hartmann's resection with temporary colostomy | Not relevant |

- NR: Not Reported; CT: Computer Tomography; Rx: Radiogram.

Clinical Case 1 (Iaccarino and Venetucci, 2012)

No details were reported other than a devastating sigmoid infarction, probably following the Tauber's procedure without intraoperative phlebography (Table 1).

Clinical Case 2 (Spiezia et al., 2013)

A twenty-one-year-old patient suffered postoperative abdominal pain arising 36 hr after Tauber's procedure for a painful left varicocele (grade III) with oligospermia and asthenospermia. Blood tests showed neutrophilic leucocytosis; a CT scan showed a thin layer of effusion along the left lateroconal fascia (formed by the Zuckerkandl fascia, which continues anterolaterally beyond the left kidney and fuses with the parietal peritoneum) and the ipsilateral pararenal space, and free fluid in the pouch of Douglas and the left inguinal canal. The patient had a moderate fever (37.8°C). A subsequent CT scan showed diffuse and marked thickening of the middle/proximal walls of the sigmoid colon with severe submucosal edema due to ischemic necrosis with thrombosis of a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery (sigmoid branch). Laparotomy confirmed the colonic ischemia involving the “left colon from the splenic flexure to the distal sigmoid tract and there were peritoneal sero-fibrinous exudate and dilation of some ileal loops.” Consequently, Hartmann's resection with a temporary colostomy was performed. Histology showed a colonic wall with coagulation necrosis, hemorrhagic transparietal extravasations with thrombosed vessels, and widespread active chronic inflammatory infiltrate (Table 1).

Clinical Case 3 (Vicini et al., 2014)

A 35-year-old man presenting with severe oligoasthenospermia and third grade varicocele underwent antegrade scrotal sclerotherapy. The patient reported intense pain in the left iliac fossa and flank immediately after an injection of atoxysclerol. There was an acute abdomen with positive Blumberg's sign, abdominal distension, and torpid peristalsis. A CT scan revealed small air bubbles in the mesenteric circulation of the sigmoid and descending colon. The clinical picture worsened with necrosis of the descending and sigmoid colon, as revealed by a further CT-scan, so a colic resection with temporary colostomy was performed (Table 1).

Clinical Case 4 (Fulcoli et al., 2013)

A 34-year-old man suffering grade IV idiopathic varicocele with mild testicular pain, severe oligoasthenozoospermia and infertility underwent an antegrade sclerotherapy according to Tauber's surgical technique after an intraoperative phlebogram. The patient complained of abdominal and inguino-scrotal pain with nausea and vomiting after half an hour. After ineffective symptomatic therapy, the patient underwent a CT scan with no initial evidence of bowel ischemia. Despite a partial clinical amelioration over the following 36 hr, the abdominal pain afterwards worsened with signs of peritoneal irritation and leucocytosis. An updated CT scan showed thickening of the sigmoid colon with pneumatosis, and colonoscopy demonstrated vascular infarction. Consequently, the patient underwent a laparoscopy confirming segmental infarction of the sigmoid colon, for which a Hartmann resection with temporary colonstomy was successfully performed. Microscopic examination revealed a massive venous thrombosis in the mucosa and submucosa of the resected colon (Table 1).

By retrieving and reviewing the CT examination, a significant collateral communication was found between the proximal portion of the testicular vein and the left colic vein (Fig. 2).

CT scan reconstruction of abdominal section showing the significant collateral communication between the proximal portion of the testicular vein and the left colic vein. Yellow arrows show the collateral communication between the Testicular (*) and the left colic (#) veins. Section 1: Transverse section; Section 2: Coronal section. Section 3: Inclined coronal section; Section 4: Magnification of Section 3. A: Anterior; P: Posterior; R: Right; L: Left; H: Head; F: Feet. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

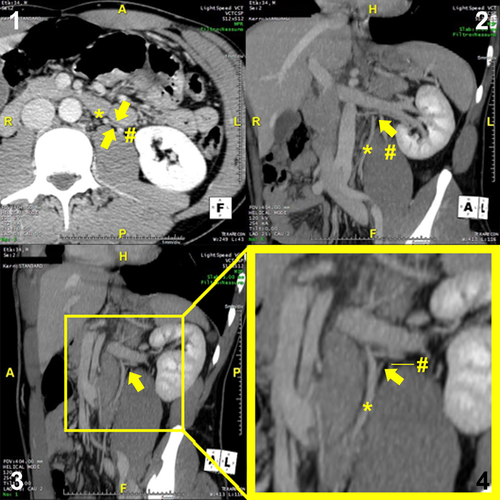

Tauber's surgical procedure consists of the following steps (Tauber and Pfeiffer, 2006). The spermatic cord along with the scrotal skin is clenched between the fingers, and a transverse incision is made in the scrotum below the external inguinal ring. The subcutaneous tissue is incised until the external spermatic fascia becomes visible. The spermatic cord is mobilized and a clamp is positioned underneath it to allow a vessel loop to be placed to include the spermatic duct. The external spermatic fascia and the cremasteric fascia are incised, and the pampiniform plexus is exposed. A dilated plexus vein is selected and dissected and distally ligated. After incision, a thin-walled cannula is introduced in an antegrade fashion toward the internal spermatic vein and secured with a single ligature. Nonionic contrast medium is injected to show the internal spermatic vein by fluoroscopy, to ensure that the contrast medium is draining through it. Subsequently, 1 mL of air followed by 3 mL of the sclerosing agent is injected in an antegrade direction while the patient performs the Valsalva maneuver. The cannula is removed and the vein is ligated proximally, the opened spermatic cord fascia is closed with a suture, and the spermatic cord is repositioned. The skin is sutured (Fig. 3).

Tauber's procedure (antegrade scrotal sclerotherapy). (A) A 1.5–2.0 cm long transverse incision is made in the scrotum 1.5–2.0 cm below the external inguinal ring. The subcutaneous tissue is incised until the external spermatic fascia becomes visible. (B) After the spermatic cord has been mobilized a clamp and a vessel loop are sequentially positioned underneath it. (C) The external spermatic fascia and the cremasteric fascia are incised, the pampiniform plexus is exposed, and a dilated and straight plexus vein is selected, dissected and distally ligated. (D) After incision, a thin-walled cannula is introduced in an antegrade fashion toward the internal spermatic vein and secured with a single ligature. Then, 3–5 mL of a nonionic contrast medium is injected to reveal the internal spermatic vein by fluoroscopy. After it has been ensured that the contrast medium is draining through the spermatic vein, 1 mL of air followed by 3 mL of the sclerosing agent is injected in an antegrade direction while the patient performs the Valsalva maneuver. The cannula is removed and the vein is ligated proximally. The opened spermatic cord fascia is closed with a suture and the spermatic cord is repositioned. The skin is sutured. (Modified from Tauber and Pfeiffer, 2003). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The procedure can be complicated by several subsequent events reported in the literature such as scrotal hematoma, hydrocele, erythema, sterile epididymitis due to paravascular application of the sclerosing substance, chemical orchitis and/or testicular atrophy (accidental sclerotherapy of the testicular artery), thrombophlebitis, partial abdominal wall necrosis (accidental sclerotherapy of the cremasteric artery), injection into the cremasteric or deferential veins (uneventful as they drain into the iliac veins with a rapid dilution of the sclerosing substance), or injection into the ductus deferens with subsequent complete obstruction (Mazzoni et al., 2001; Tauber and Pfeiffer, 2003; Fulcoli et al., 2013; Spiezia et al., 2013).

However, only a few case reports have been published on a further unusual complication, ischemic colitis or sigmoid infarction (Iaccarino and Venetucci, 2012; Fulcoli et al., 2013; Spiezia et al., 2013; Vicini et al., 2014). This ischemic colitis has been hypothetically ascribed to: an arterial thrombosis due to pre-existing vascular disease combined with a sudden perioperative hypotension (Spiezia et al., 2013); an accidental intra-arterial (testicular artery) injection of the sclerosis fluid, refluxing into the aorta from the spermatic artery, and following the flow of the inferior mesenteric artery with occlusion damage (Spiezia et al., 2013); erroneous sclerotherapy of the cremasteric vein (tributary of the external iliac vein) or the deferential vein (tributary of the internal iliac vein) (Fulcoli et al., 2013); or an (unproven) abnormal communication between the testicular and mesenteric circulations (Spiezia et al., 2013). Apart from an overt technical error during injection of the sclerosing substance, the most relevant and credible hypothesis that remains, potentially supported by scientific evidence, is the last-named: an abnormal communication between the spermatic and mesenteric circles, part of the systemic-portal anastomoses.

A portal-systemic communication (anastomosis) is a system in which the portal venous system communicates with the systemic venous system. These alternative routes are available because the portal vein and its tributaries have no valves, which have become incompetent owing to the progressive dilatation of small naturally-occurring venous anastomoses; hence blood can flow in a reverse direction to the inferior vena cava (Paquet, 1982).

As previously stated (Lechter et al., 1991), modern anatomy textbooks often mention anatomical variations and atypical communications of the above-mentioned portal-systemic anastomoses only summarily, rarely stressing the anastomotic communication between the left colic vein (portal system) and left testicular vein (systemic). Nevertheless, this anastomosis is clinically relevant in daily practice for clinicians and surgeons (Bigot et al., 1997). (a) Anastomoses between the gonadal and portal venous systems are commonly recognized by surgeons as small collateral veins that bleed readily during dissection of the colonic fascia (Donovan and Winfield, 1992), (b) Whenever there is thrombosis in the mesenteric venous system it causes necrosis of the small bowel more frequently than necrosis of the colon, possibly because of a number of anastomoses between the gonadal and colonic veins (Cokkinis, 1926), (c) Likewise, mesenteric infarction causes proximal rather than distal necrosis, and ligature of the superior mesenteric vein can be uneventful when performed on patients with a preexisting occlusion of the portal vessels (Linton, 1948), (d) Moreover, asymptomatic portal thrombosis extending to the distal part of the gonadal veins has been reported in patients with acute colonic inflammatory disease, diverticulitis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, pseudomembranous colitis, and appendicular abscess (Jain and Jeffrey, 1991).

There have been specific references to this particular anastomosis in more dated textbooks since the 19th century (Cruveilhier, 1834; Hovelacque, 1920; Paturet, 1958), but rarely in recent clinical textbooks (Grieme and Venbrux, 2008; Basu, 2011) or scientific papers (Bigot et al., 1997; Wishahi, 1991a, 1991b; Chudnovets et al., 2009). Conversely, left-sided gonadal-mesenteric inferior anastomoses were observed in 21% of cases in human fetuses, an ovarian-mesenteric inferior anastomosis in 24%, and a testicular-mesenteric inferior anastomosis in 19% (Szpinda et al., 2005). From the embryological point of view, anastomoses of the gonadal veins form the basis for collateral circulation with the perirenal, periureteral, inferior mesenteric and the contralateral gonadal veins, and also with the renal veins and the inferior vena cava in the retroperitoneal space. In particular, the subcardinal veins are connected to the supracardinal and the vitelline veins by multiple anastomotic channels, which form retroperitoneal venous communications (Macchi et al., 2003; Sadler, 2017).

The scarcity of such references contrasts with the published epidemiological data, which reveal abnormal communications between the left colic and left testicular veins in 7.8% (Salerno et al., 2000) to 9.2% (Bigot et al., 1997) of cases, described as a venous trunk with competent valves (5.1%), or communicating venules (3.1%), or single/double anastomoses (1%), with only an outline estimate (77%) reported by Wishahi (1991b). However, despite the hypothetical prevalence of this anatomical variation, some urologists and interventional radiologists report that they cannot correctly visualize it by intraoperative phlebography, although they are aware of its possible presence and check carefully (Fulcoli et al., 2013; Vicini et al., 2014). Consequently, there is a catastrophic adverse event.

A number of hypotheses could explain the failure to identify this (un)common anatomical finding.

First, owing to the injection of the sclerosing substance with air and the concurrent Valsalva maneuver, the intravenous pressure within the left testicular vein could suddenly rise, causing the inversion of blood flow through a small collateral vein with normally competent valves (thus not detectable during the intraoperative phlebography) into the left colonic vein.

Our CT scan reconstruction failed to show such an anastomosis, but we have identified an anatomical variation consisting of a communication between the proximal portion of the testicular and left colic veins (Fig. 2). We believe there was also a lower communication between the same veins in this case. On this point a number of authors have reported that multiple aberrant anastomoses could be present simultaneously between the testicular vein and nearby veins, including the left colic vein (Lechter et al., 1991; Wishahi, 1991a, 1991b; Bigot et al., 1997). It was not recognizable by intraoperative phlebography because of competent valves, as reported in up to 55% of cases by some authors (Bigot et al., 1997), which were destroyed when the sclerosing substance was injected, also causing vein coarctation, so it was no longer detectable on a CT scan after the complication occurred, albeit at short distance. Vicini et al. (2014) reported an interesting intraoperative phlebography apparently showing the unidentified proximal tract of a collateral between the left testicular and left colic veins (Figure 1 in their article). We hypothesized that this could be subsequently became incompetent owing to the injection of sclerosing substance, with consequent necrosis of the left and sigmoid colon as the authors described (Vicini et al., 2014).

Second, extravasation of the sclerosing substance next to the sigmoid colon could induce local inflammation with deferred venous thrombosis (Fulcoli et al., 2013; Vicini et al., 2014).

Conversely, the infrequent reporting of this complication and its devastating clinical consequences, despite the huge number of Tauber's procedures performed on a daily basis worldwide, could be explained by under-reporting of its real incidence by urologists and radiologists, since it could imply a technical error in interpreting the intraoperative phlebography. Consistent with this possibility, two of the four published reports were written by surgeons or radiologists involved in managing the colonic necrosis following scleroembolization of the left testicular vein, but not directly involved in its execution.

Moreover, Bigot et al. reported no clinically apparent complications from reflux of the sclerosing substance into the colonic, splenic, inferior mesenteric, or hepatic portal veins in their series of 500 outpatients, perhaps depending on the amount of sclerosing substance used, the pressure applied during injection, the level of origin of the collateral vein, and the presence of multiple venous collaterals.

An intriguing role for such systemic-portal communications can also be hypothesized. These communications could be physiologically active, contributing to the pathogenesis of varicocele: a venous flux from the colonic vein could overload the testicular vein with consequent stasis at the level of the pampiniform plexus. Further studies could be undertaken to assess this hypothesis.

Overall, we demonstrated the pathophysiological role of a vascular anatomical variation in a real clinical scenario, linking this variation to the clinical complication, thus highlighting the importance of a deep knowledge of anatomy in the daily clinical practice of many physicians including urologists and radiologists. On this basis, given a knowledge of classical anatomy and its variants, intraoperative phlebography is mandatory in this kind of surgical procedure so that the potential presence of an anastomosis between the testicular and the left colonic veins can be assessed.

CONCLUSIONS

An anatomical variation consisting of a communication between the testicular and left colic veins has been described from the clinical point of view. The implications are of great importance for both the outcomes of surgical interventions and the medico-legal implications in a context of overwhelming litigation arising from a major personal injury resulting from a minor interventional procedure. On this point, it must be remembered that ischemic colitis cannot be always prevented even if an intraoperative phlebography is performed, as shown in this article and concluded by the prosecutor's medical consultants. The pressure of innovative technologies and new surgical procedures, combined with the pressure exerted by the increasing number of filed lawsuits, has renewed interest in studying unusual anatomical variants.