Competing Institutional Logics in Corporate ESG: Evidence From Developing Countries

ABSTRACT

Drawing on competing institutional logics theory, we examine the institutional complexity of corporate sustainability practices in an underexplored context of developing economies. Analyzing 11,757 firm-year observations from 19 emerging countries across Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America between 2013 and 2022, we document a U-shaped relationship between ESG performance and firm value, with financial performance failing to mediate this nexus. This indicates that the market remains the dominant institutional logic in corporate ESG. Shareholders initially penalize firm value when companies increasingly incorporate community logic through ESG initiatives, despite their positive impact on profitability. However, as the benefits of ESG strategies become more apparent, shareholder valuation improves, allowing market and community logics to coexist. We term this temporality of logics the “transient penalty zones.” Our findings highlight the need to eliminate transient penalty zones through effective communication and standardized sustainability disclosure to prevent greenwashing and sustain investor trust.

1 Introduction

Corporate sustainability has gained significant momentum as investors and managers fast-growingly incorporate a broad spectrum of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into their business strategies (Kumar et al. 2021; Gianfrate et al. 2024). Sustainable investing assets in Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan reached $35.3 trillion in 2020, marking a 55% increase from $22.8 trillion in 2016 (GSIA 2022). This trend is not exclusive to developed regions. The Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) Global Investment Research reveals that 60% of investors in the Asia-Pacific expect to incorporate ESG into investment decisions (Cornock 2021). The CAGR of sustainable bonds in ASEAN grew exponentially at 185% between 2016 and 2020 (EY 2022).

However, firms' ESG initiatives have sparked fundamental debates between proponents of shareholder and stakeholder theories. The former views ESG as non-revenue-generating, leading to suboptimal firm performance and a lower firm value (Friedman 1970). In contrast, stakeholder theory takes the opposite view (Freeman 1967). Firms maintain a social contract with non-shareholder stakeholders, including society and the environment, to gain societal legitimacy (Suchman 1995). By addressing the interests of diverse stakeholders, firms can develop unique internal resources, leading to sustained competitive advantage and higher firm value, consistent with the resource-based view (RBV) (Barney 1991).

The strong empirical support for both perspectives creates a puzzle (Gillan et al. 2021). One strand of the literature concludes that the adoption of ESG is conducive to firms' profitability widely measured by return on assets (ROA) and/or return on equity (ROE) (Xie et al. 2019; Qureshi et al. 2021; Shin et al. 2023). As profitability increases, overall firm value commonly measured by Tobin's Q and/or price-to-book value (PBV) is also expected to improve. Other studies, however, illustrate that investors may not positively factor higher ESG performance into firm valuations and sometimes respond unfavorably to highly rated ESG companies by diminishing their market value despite these companies delivering superior financial performance (Di Giuli and Kostovetsky 2014; Behl et al. 2022).

One potential cause of this puzzle lies in the differing motivations among stakeholders involved in corporate ESG initiatives, particularly between investors and managers. As Starks (2023, 1837) rightly puts it, “much of the confusion is due to differences in whether motivation arises from value or values, that is, from regarding the ESG qualities of an investment as important to its financial value or, as consistent with one's values.” In this context, the standard agency framework and stakeholder theory commonly used in previous studies offer only “a simplistic view” (DesJardine et al. 2023, 10) when analyzing motivations that extend beyond purely financial considerations.

In this study, we apply institutional logics theory to explain the conflicting empirical evidence on the ESG–firm performance nexus and propose the following research questions: Can institutional logics theory enhance our understanding of the relationship between ESG performance and firm value in the Global South? Is there a temporality dimension of institutional logics on the ESG–firm value relationship?

The use of institutional logic framework allows a deeper analysis of the dynamic behavior of different economic agents stemming from their distinct “assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 804) toward the corporate ESG practices (Reay and Hinings 2009). Studying the global corporate ESG is complex as it involves many entities, including shareholders, managers, consumers (society), and government (DesJardine et al. 2023). Each possesses logic toward the corporate ESG implementations that may be coexisting or competing due to the influence of different institutional orders (foundational societal structures), namely, the market, corporation, professions, state, family, religions, and community (Greenwood et al. 2011; Thornton et al. 2012). We focus on the market and community logics for brevity, aligning with the frameworks of Venkataraman et al. (2016) and Chu et al. (2024). Whereeas market logic prioritizes financial efficiency as the primary objective of business strategies, community logic emphasizes equity and a holistic goal to maximize the integrated value across finance, society, and the environment (Silva and Nunes 2022; Siefkes et al. 2024).

Our study focuses on developing economies, as most research on the ESG-firm performance relationship has predominantly been conducted in developed countries (Gillan et al. 2021), with the noticeable exception of China (Liu and Kong 2021; Zhou et al. 2022; Cheng et al. 2024). Similarly, many studies employing institutional theory to explain the coexistence of logics and their dynamic interactions in sustainable finance and ESG practices have been carried out in the context of the Global North (see, for instance, Beunza and Ferraro 2019; Gautier et al. 2023; Guix et al. 2025). Emerging markets, however, have distinct institutional characteristics compared to their developed counterparts. These differences significantly shape the dynamic interactions between investors and managers in the context of sustainability (Ioannou and Serafeim 2023), warranting greater attention from academic researchers. As Foo et al. (2020, 289) rightly put it, “… because emerging economies differ markedly in their institutional development from developed economies, this prior research [regarding developed economies] is less likely to be useful to understand … emerging regions.”

For example, studies suggest that managers in developing economies are less incentivized to engage in greenwashing for social legitimacy (Lim and Tsutsui 2012; Roulet and Touboul 2015). This is because investor attention to ESG issues in these regions is still in the early stages. According to a report by the Global Ethical Finance Initiative (GEFI 2023), only 47% of investors and depositors in the Global South consider reducing social inequality and injustice to be important, compared to 72% in the Global North. Similarly, only 53% of individuals in the Global South express concern about environmental issues and climate change, in contrast to 75% in the Global North. However, the pressure on managers to play a more significant role in ESG is notably higher in developing countries, where 77% of CEOs feel this pressure strongly, compared to 63% of CEOs in developed nations (UNGC 2023).

Using instrumental variable two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression within Baron and Kenny's (1986) framework, we analyze 11,757 firm-year observations from 19 emerging economies in Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and South America between 2013 and 2022.

Our findings reveal that investors penalize firms' market value despite the positive impact of ESG performance on profitability. Traditional theories, such as shareholder and stakeholder, do not fully account for this outcome. Shareholder theory, for instance, would predict a positive investor reaction due to the increased profitability of high ESG-performing firms, whereas stakeholder theory would also expect a positive relationship between ESG performance and market value in the first place. We argue that the institutional theory offers a more robust explanation, attributing this phenomenon to the dominance of market logic within corporate ESG practice in the Global South. This market logic fosters a perception that ESG strategies may negatively impact firms' financial performance despite empirical evidence showing the contrary (see Gümüşay et al. 2024).

This tendency is particularly evident in the short run, where the positive effects of ESG performance on profitability are still ambiguous, consistent with findings by Barnett and Salomon (2012) and Nollet et al. (2016). In the long run, however, as the beneficial impact of ESG practices on firm performance becomes clearer, investors increasingly incorporate ESG strategies into firm valuations.

We term this interaction between market and community logics as “transient penalty zones.” Initial negative investor reactions may stem from concerns about greenwashing in ESG practices, as highlighted in previous studies (Du 2015; Treepongkaruna et al. 2024). Such reactions prompt investors to further assess whether firms' ESG initiatives genuinely reflect sustainable strategies capable of generating long-term value creation (LTVC). Once companies substantiate the value of their ESG efforts, investors are more likely to recognize and integrate these positive impacts into valuations (Barnett and Salomon 2012; Nollet et al. 2016). This phenomenon underscores the inter-temporal nature of institutional logics in corporate ESG practices, leading to the coexistence, instead of competition, of market and community logics.

Our study makes several significant contributions to the business literature. First, by focusing on the geographical context of emerging economies, we extend the corporate ESG literature, which has predominantly emphasized the Global North (Gillan et al. 2021). Second, we demonstrate that the institutional logics framework is a valuable tool for addressing the complexities of global corporate ESG, building upon its use in examining state-owned enterprises (Cheung et al. 2020), business strategy (Ko et al. 2021), supply chain (Silva and Nunes 2022), venture capital (Siefkes et al. 2024), and hybrid organization (Jatmiko et al. 2025). Third, we contribute to the literature on the temporality of institutional logics in the corporate sustainability domain, building on the works of Dau et al. (2022), Darnall et al. (2024), and Gümüşay et al. (2024). Finally, we contribute to the debate on the impact of corporate ESG engagement on firm performance. Our framework of the temporality of competing institutional logics introduces the concept of “transient penalty zones” in corporate sustainability in the Global South. This concept helps explain the discrepancies in empirical results across different geographical territories, where some studies suggest a positive impact of ESG and others indicate the opposite (Gianfrate et al. 2024; Zhu et al. 2024).

2 Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1 Competing Logics in Corporate Sustainability

An organization is formed by entities with shared ethical objectives. However, they may possess different logics stemming from distinct beliefs, values, and axioms through which individuals define the meaning of life (Thornton et al. 2012). As the construction of meaning varies across different agents, the dominant institutional orders, including market, community, state, corporation, religion, profession, and family, determine the objectives of institutions (Reay and Hinings 2009), which is eventually transmitted into their decision-making process and strategies (Almandoz 2014). For the sake of brevity, our analysis focuses on market and community logics, consistent with Venkataraman et al. (2016) and Chu et al. (2024) (see Table 1).

| Market | Community | |

|---|---|---|

| Core values | Value-free and competitiveness | Equity and common goals |

| Basis of norms | Self-interest | Group membership |

| Basis of attention | Legitimacy in the market | Member contributions |

| Basis of strategy | Self-efficiency for profit maximization | Increase status and position |

| Source of authority | Shareholders activism | Social contract |

| Source of legitimacy | Market value | Unity of vision |

| Informal control mechanism | Industry analyst | Transparency of actions |

- Source: Authors.

The market logic is based on the assumption of a free and competitive market, where the economic agents are utility maximization entities with self-interest norms (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Its main authority comes from shareholders' activism driven by their expectations of the firm value, making operational efficiency and profit the heart of its business strategies (Skelcher and Smith 2015). Therefore, as far as the corporate ESG is concerned, this institutional order considers value as a mare financial sustainability.

On the other hand, the community logic champions equity and common (social) interests (Thornton et al. 2012). It represents collective connections among individuals, emphasizing interpersonal and personalized relationships. Customers are among the most important communities that have been growingly demanding more sustainable products, as consistently suggested by recent market studies (Bar Am et al. 2023). They endorse the attainment of intergenerational, intragenerational, and physiocentric justice. This institutional order is also embodied in the ESG-related nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and lobbyists.

2.2 The Dominance of Market Logic

Indeed, distinct institutional logics are evident not only between investors and managers but also among various types of investors. Starks (2023) divides investors into four different types: (i) traditional, (ii) classic ESG, (iii) socially responsible, and (iv) impact investors. Traditional investors follow a market-dominant logic, aiming solely to maximize risk-adjusted returns. Classic ESG investors, while also return-focused, limit their investment universe by excluding “sin sectors” to maintain ESG compliance. However, their investment strategy remains to obtain a greater-than-market return. Socially responsible investors are willing to accept slightly lower-than-market returns to achieve social and environmental impact. Although market logic still influences them, their focus shifts toward community by maximizing integrated values that combine financial, environmental, and social outcomes. Finally, impact investors, which represent a small minority in the market, prioritize environmental and social outcomes and accept lower risk-adjusted returns, as their dominant logic centers on community logic (see Appendix A for a summary of the spectrum of investors' logic).

A plethora of empirical literature suggests that the proportion of impact investors remains small. Giglio et al. (2023) document that sustainable investors who consider ethics as their motive for investments are only 25%, whereas other respondents consider risk, return, and other pecuniary benefits as their primary motives. The results are derived from US-based investors who already have relatively higher awareness regarding ESG as compared to developing economies (UNGC 2023). Krueger et al. (2020) also point out that 5 out of 7 highest motives in ESG investing are influenced either by market or state, namely, return, risk, tail risk, reputation, and legal. Riedl and Smeets (2017) argue that social preference is not the only motive of ESG investing; investors also engage with sustainable assets for social signaling purposes. They also find that the social preference motive increases the likelihood of investors choosing ESG corporations by 14% but does not influence the amount of money they allocate to such an investment. Giglio et al. (2023) confirm Riedl and Smeets (2017) that, agnostic to the motives, investors only allocate meaningful amounts of investments on ESG should they anticipate the investment to surpass market performance.

Given that a significant portion of investors are either traditional or classic ESG, it is plausible to expect market logic to dominate investor behavior, leading to adverse reactions toward firms' engagement in ESG activities. Contrary to the mainstream empirical studies, this study supports the negative relationship between firms' ESG performance and their market values, consistent with Di Giuli and Kostovetsky (2014) and Behl et al. (2022). This relationship is even more pronounced in the spatial context of developing economies, where investors' internal motivation toward social and impact investments is more limited (UNGC 2023). In such contexts, investors often perceive the firm's adherence to ESG principles as non-revenue-generating, and therefore, they penalize its expected future cash flow, resulting in a lower market value.

Unlike shareholder theory, which suggests that firms engaging in ESG activities may suffer financially, institutional theory predicts that investors' negative sentiment toward ESG may stem from preconceived assumptions or beliefs rather than from the actual impact of ESG on firm performance. As Gümüşay et al. (2024, 5) state, “the propensity to prioritize specific logics impacts how they attend to institutional expectations, demands, and prescriptions.” This explains why negative perceptions persist, even though numerous studies indicate that high-performing ESG firms can achieve superior financial performance compared to, or at least on par with, their low-performing counterparts (Xie et al. 2019; Qureshi et al. 2021; Shin et al. 2023).

There is a surprisingly limited body of empirical literature that applies institutional logic to ESG practices in developing economies. However, related studies have been conducted in the areas of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and religious-based hybrid organizations. Chu et al. (2024) report that market logic remains dominant in the CSR activities of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in India, as these organizations prioritize activities that generate positive externalities over negative ones to enhance their competitive advantages. Similarly, Zhao and Lounsbury (2016) highlight that market logic is not only dominant but also crucial for religious-based microfinance institutions in developing economies to secure larger capital bases, ensuring financial sustainability over outreach and social impact.

Asutay et al. (2023) observe that market logic also prevails in the trading behavior of retail investors in the Islamic stock market in Indonesia, overshadowing religious logic. This is despite the fact that incorporating stricter religious logic into equity investing does not compromise portfolio performance (Alotaibi et al. 2022). Further, Asutay and Yilmaz (2025) expand on this issue in the broader context of emerging economies. They contend that the hegemony of market logic over religious logic is evident in the disembedded nature of Islamic finance practices, where debt-based instruments dominate over equity-based instruments, which are more closely aligned with Islamic principles.

Based on the above discussions, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.The ‘market’ remains the dominant logic in corporate ESG practices within emerging economies.

To enable empirical testing, we refine Hypothesis 1 into the following testable sub-hypothesis (Hypothesis 1a):

Hypothesis 1a.ESG performance has a negative relationship with firm value despite its positive impact on the firm's financial performance.

2.3 Temporality of Logics in Corporate Sustainability

Having said that, the institutional logic theory also predicts the possibility of a transient relationship between ESG and firm value. In other words, market and community logics continuously interact in shaping corporate sustainability. At certain times and in specific contexts, these logics may be in competition, whereas in other instances, they can achieve harmonious coexistence. Although institutional logic is often rigid, it also possesses elements of temporality and malleability, allowing them to be dynamic across different contexts of time and space (Gümüşay et al. 2024). The literature on institutional complexity also suggests that logics are not always in direct conflict; they can coexist or even reinforce each other in specific contexts (Greenwood et al. 2011). This is why some studies have documented a non-monotonic relationship between ESG and firm value (Barnett and Salomon 2012; Darnall et al. 2024).

Nollet et al. (2016) assert that the market reacts negatively in the short term but positively in the long term to firms' ESG involvements. On the other hand, Darnall et al. (2024) argue for the existence of penalty zones, where excessive resource allocation to ESG can turn a positive impact into a negative one. Short-term investors (transactional shareholders) often experience more asymmetric information, leading to noise in their reactions to firms' ESG strategies (Oehmichen et al. 2021). In contrast, long-term investors (durable shareholders) are more receptive to innovation and strategies, as they possess the ability to thoroughly evaluate these factors for sustaining firms' competitiveness, thereby reducing asymmetric information (Connelly et al. 2010).

The inter-temporal shift in the nexus between ESG and firm performance can be attributed to initial investor concerns about greenwashing or doubts regarding the authenticity of ESG commitments (Treepongkaruna et al. 2024). Investors may initially view ESG announcements skeptically, questioning the firm's genuine commitment or the long-term impact of such practices (Du 2015). These ESG efforts may be seen as mere marketing tactics (greenwashing) until firms substantiate them with consistent, tangible results (Zharfpeykan 2021). The initial skepticism toward ESG initiatives may lessen as the positive impact of ESG on firm performance becomes clearer (Barnett and Salomon 2012; Nollet et al. 2016).

The challenge of assessing short-term ESG outcomes contributes to investor caution, leading them to wait for clearer, long-term evidence before positively adjusting stock prices. This hesitancy is particularly pronounced in developing economies, where investors often anticipate adverse effects stemming from weak governmental institutions, lower shareholder protection, insufficient sustainability disclosure and reporting standards, and weak enforcement mechanisms (Julian and Ofori-dankwa 2013). However, CSR literature documents that the practice of greenwashing tends to be relatively lower in developing economies with high market competition as the incentive to gain legitimacy from such activities is relatively low (Lim and Tsutsui 2012; Roulet and Touboul 2015).

Venkataraman et al. (2016) highlight that, though it is challenging to reconcile market and community logic within the context of tribal development initiatives led by NGOs in India, such a convergence is possible when both the beneficiaries and their families gain sufficient trust in the NGO's market-based activities. In the context of ESG activism, investors' concerns about potential greenwashing can similarly be alleviated as they observe clearer links between ESG initiatives and positive financial performance. When concerns about greenwashing are mitigated and ESG initiatives demonstrate tangible benefits, investors are more likely to reassess and incorporate the positive impact of ESG into valuations, effectively ending the “penalty zones.” Here, the market logic can coexist with the community one. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.The relationship between ESG and firm value in the Global South is influenced by the temporal dimension of institutional logic.

Again, for Hypothesis 2 to be empirically tested, we reframe it into the following specific and testable sub-hypothesis (Hypothesis 2a):

Hypothesis 2a.The initially negative relationship between ESG performance and firm value will become positive as the financial benefits of ESG initiatives become more apparent.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data

To prove the above hypotheses, this study focuses on developing economies. After filtering for data availability across countries, our dataset consists of 11,757 firm-year observations of non-financial companies listed in 19 emerging countries across Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America, specifically in (1) Argentina, (2) Brazil, (3) Chile, (4) China, (5) Colombia, (6) Egypt, (7) Hungary, (8) India, (9) Indonesia, (10) Malaysia, (11) Mexico, (12) the Philippines, (13) Poland, (14) Russia, (15) Saudi Arabia, (16) South Africa, (17) Thailand, (18) Türkiye, and (19) the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The study utilizes a 10-year historical dataset spanning from 2013 to 2022, the most recent period for which ESG score data provided by the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) is largely complete for our sample. The use of ESG scores from LSEG aligns with most ESG studies, such as Albuquerque et al. (2019) and Drempetic et al. (2020). While acknowledging limitations in the methodology for representing corporate ESG performance, this database stands out for providing the most comprehensive ESG data compared to other rating providers (Baran et al. 2022). LSEG ESG scores also demonstrate a high correlation with other leading ESG ratings, such as Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini (KLD), Moody's ESG (Vigeo-Eiris), MSCI, S&P Global (RobecoSAM), and Sustainalytics (Berg et al. 2022). Table 2 defines our variables and outlines the data sources.

| Variable | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||

| Tobin's Q (TBQ) | Firm value: Market capitalization and total debt over total assets (replacement cost) | LSEG |

| Price-to-book value (PBV) | Firm value: Firm's market value over its book value | LSEG |

| Independent variable | ||

| ESG score (ESG) | Composite score of ESG performance (environment, social, and governance) | LSEG |

| E score (E) | Environmental dimension score | LSEG |

| S score (S) | Social dimension score | LSEG |

| G score (G) | Governance dimension score | LSEG |

| Mediating variable | LSEG | |

| Return on equity (ROE) | Profitability: Net profit over equity | LSEG |

| Return on asset (ROA) | Profitability: Net profit over total assets | LSEG |

| Control variable | LSEG | |

| Firm size (Size) | Natural log of the total assets | LSEG |

| Financial leverage (Lev) | Total assets minus total equity standardized by total assets | LSEG |

| Cash flow (CF) | Cash flow over total assets | LSEG |

| Total asset turnover (TAT) | Net operating income minus gross profit and operational expense standardized by total assets | LSEG |

| Revenue growth (RG) | Revenue growth from the previous year | LSEG |

| Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) | Yearly per capita GDP | International Monetary Fund (IMF) Database |

| Institutional quality (IQ) | Equally weighted index of control of corruption, political stability, regulatory quality, rule of law, and voice and accountability | World Development Indicators |

| Regional dummy | Regional dummy for South America, Africa, East Europe, West Europe, and Asia where the latter become the basis | |

| Covid dummy (DCov) | Valued 1 for 2020–2021 and 0 for otherwise | |

| Sector dummy (DS) | Sector dummy employing Thomson Reuters' classifications | |

| Instrumental variable | ||

| Mean_ESG | Mean of ESG score by industry | LSEG |

| In_ESG | Initial level of ESG by the company | LSEG |

- Source: Authors.

3.2 Methods

We then evaluate the dynamic interactions between market and community logics, that is, Hypothesis 2, by examining the temporality of the above relationship. In so doing, we incorporate the squared term of ESG scores (and its dimensions) into Equations (1–3) to test for non-monotonicity in the relationship between ESG performance and firm value. To ensure the robustness of the nonlinear relationship between the variables, we also employ Lind and Mehlum's (2010) methodology, consistent with previous studies, such as Darnall et al. (2024) and Li et al. (2024). Unlike traditional tests for nonlinearity that focus solely on the sign and significance of the parameters for ESG ( ) and ESG_SQ ( ), Lind and Mehlum's (2010) approach evaluates nonlinearity based on three criteria: (i) the turning point ( ) must lie within the range of observed data ; (ii) the overall Sasabuchi (1980) must be statistically significant; and (iii) the lower bound slope ( ) must be negative [positive], whereas the upper bound slope ( ) must be positive [negative] for the U-shaped [inverted U-shaped] relationship.

This study also performs a series of robustness checks by (i) excluding countries with a small number of firms, (ii) adjusting for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, (iii) replacing TBQ with PBV, (iv) substituting ROE with ROA, and (v) addressing endogeneity issue with the instrumental variable (IV) regression of two-stage least squares (2SLS), consistent with the previous literature (see El Ghoul et al. 2011; Benlemlih and Bitar 2018). The endogeneity issue, in particular, may arise from omitted variable bias, measurement error, or reverse causality, all of which can lead to biased and inconsistent parameter estimates. In the context of the ESG–firm performance nexus, reverse causality is particularly relevant. Although ESG scores can influence firm performance, firm performance can, in turn, affect a company's ESG initiatives and scores (El Ghoul et al. 2011; Benlemlih and Bitar 2018). IV-2SLS is widely regarded as an effective method to address such endogeneity concerns (Wooldridge 2010). Our use of IV-2SLS aligns with established practices in the literature, including studies by El Ghoul et al. (2011) and Benlemlih and Bitar (2018), which also employ this approach to resolve endogeneity issues.

4 Findings and Discussion

4.1 Descriptive Analysis

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study. On average, firms exhibit moderate ESG performance, with scores of 36.76 for environmental (E), 40.57 for social (S), and 49.24 for governance (G), yielding an aggregate score of 41.64. The G pillar (consisting of CSR strategy, management, and shareholders aspects) has been a long-standing concern for companies, predating the E and S. This precedence is reflected in its comparatively higher score and lower deviation. The E demonstrates the lowest scores, with some firms even obtaining zero. This underscores the urgent need for significant improvement in their focus on emission reduction, innovation, and efficiency aspects. A notable divergence in environmental practices across firms and industries is also evident from its high standard deviation.

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Median | St. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBQ | 11,687 | 1.835 | 1.286 | 1.371 | 0.612 | 5.797 |

| PBV | 11,409 | 2.624 | 1.797 | 2.263 | 0.396 | 8.804 |

| ESG | 5266 | 41.639 | 40.627 | 19.282 | 10.871 | 76.065 |

| E | 5274 | 36.759 | 34.907 | 25.278 | 0.000 | 81.936 |

| S | 5274 | 40.566 | 38.299 | 24.834 | 4.555 | 84.879 |

| G | 5274 | 49.236 | 49.101 | 20.89 | 0.055 | 97.313 |

| ROE | 11,702 | 0.124 | 0.114 | 0.094 | −0.045 | 0.335 |

| ROA | 11,086 | 0.065 | 0.055 | 0.054 | −0.019 | 0.193 |

| TAT | 11,088 | 0.086 | 0.072 | 0.062 | 0.001 | 0.236 |

| RG | 11,063 | 0.088 | 0.062 | 0.209 | −0.262 | 0.583 |

| Size | 11,088 | 21.155 | 21.167 | 1.567 | 18.275 | 23.978 |

| Lev | 11,088 | 0.518 | 0.506 | 0.227 | 0.155 | 0.979 |

| CF | 11,725 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.045 | −0.072 | 0.118 |

| GDP | 11,757 | 9865 | 9905 | 3841 | 3559 | 20,442 |

| IQ | 11,757 | −0.283 | −0.462 | 0.409 | −1.117 | 1.155 |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2. As the variables variation of distributions (Std. dev.) are quite significant, we perform 5%–95% winsorizing to control for potential outliers.

- Source: Authors.

The country-level analysis in Table 4 consistently supports these arguments. India boasts the highest average ESG score (62.19) as well as scores in all three dimensions, followed by Colombia (55) and Türkiye (52.52). Conversely, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and China rank among the lowest ESG performers, with respective scores of 22.68, 30.57, and 34.31. Saudi Arabia records the lowest score in E (21.77), whereas Egypt demonstrates the weakest performance in S (16.90).

| ESG | E | S | G | TBQ | PBV | ROE | ROA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South America | 46.352 | 42.730 | 49.235 | 49.860 | 1.308 | 1.904 | 0.101 | 0.047 |

| Argentina | 38.504 | 29.970 | 38.256 | 48.908 | 1.493 | 2.403 | 0.105 | 0.051 |

| Brazil | 52.362 | 55.735 | 61.081 | 52.797 | 1.228 | 1.563 | 0.118 | 0.054 |

| Chile | 42.855 | 37.569 | 43.148 | 48.183 | 0.965 | 1.023 | 0.087 | 0.037 |

| Colombia | 54.999 | 48.217 | 60.070 | 56.754 | 1.001 | 1.414 | 0.086 | 0.034 |

| Mexico | 47.063 | 44.071 | 49.512 | 48.042 | 1.499 | 2.389 | 0.104 | 0.052 |

| Asia | 39.259 | 33.335 | 36.348 | 49.172 | 2.032 | 2.888 | 0.127 | 0.068 |

| China | 34.310 | 30.269 | 26.236 | 49.067 | 2.432 | 3.396 | 0.135 | 0.071 |

| India | 62.188 | 58.408 | 66.798 | 62.154 | 3.262 | 4.651 | 0.162 | 0.104 |

| Indonesia | 43.537 | 33.120 | 48.387 | 45.888 | 1.902 | 2.868 | 0.145 | 0.074 |

| Malaysia | 44.861 | 35.739 | 48.641 | 49.520 | 1.391 | 1.765 | 0.093 | 0.056 |

| Philippines | 45.133 | 40.125 | 47.363 | 50.894 | 1.577 | 2.723 | 0.140 | 0.055 |

| Saudi Arabia | 30.570 | 21.772 | 26.372 | 43.347 | 1.828 | 2.660 | 0.119 | 0.069 |

| Thailand | 51.715 | 44.697 | 57.442 | 51.663 | 1.777 | 2.754 | 0.133 | 0.069 |

| UAE | 34.952 | 25.060 | 30.840 | 51.027 | 1.067 | 1.524 | 0.091 | 0.054 |

| Africa | 43.746 | 40.700 | 44.757 | 52.930 | 1.198 | 1.542 | 0.124 | 0.061 |

| Egypt | 22.676 | 12.927 | 16.904 | 37.645 | 1.248 | 1.697 | 0.149 | 0.066 |

| South Africa | 52.138 | 51.762 | 55.851 | 59.018 | 1.148 | 1.389 | 0.099 | 0.056 |

| East Europe | 41.387 | 39.545 | 41.501 | 45.406 | 1.213 | 1.715 | 0.115 | 0.061 |

| Hungary | 51.813 | 50.026 | 57.019 | 48.095 | 1.201 | 1.254 | 0.092 | 0.046 |

| Poland | 40.706 | 36.826 | 39.159 | 47.223 | 1.251 | 1.713 | 0.096 | 0.044 |

| Russia | 40.026 | 40.132 | 40.752 | 43.140 | 1.176 | 1.829 | 0.143 | 0.085 |

| West Europe | 52.515 | 50.335 | 56.641 | 50.830 | 1.314 | 2.116 | 0.155 | 0.076 |

| Türkiye | 52.515 | 50.335 | 56.641 | 50.830 | 1.314 | 2.116 | 0.155 | 0.076 |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2.

- Source: Authors.

The likelihood of multicollinearity in the model is also low, as the independent variables do not exhibit significant correlations with one another (i.e., Person's correlation coefficient ) (see Table 5). Some correlation among ESG dimensions is anticipated due to their interconnected nature. For instance, the correlation between E and S is particularly high at 0.77. In contrast, G diverges more distinctly, showing lower correlations of 0.34 with E and 0.36 with S.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) TBQ | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| (2) PBV | 0.862 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (3) ESG | −0.122 | −0.062 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (4) E | −0.144 | −0.091 | 0.873 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (5) S | −0.124 | −0.064 | 0.905 | 0.766 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (6) G | −0.047 | −0.018 | 0.601 | 0.342 | 0.358 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (7) ROE | 0.382 | 0.457 | 0.045 | 0.043 | 0.045 | 0.006 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (8) ROA | 0.530 | 0.485 | −0.040 | −0.040 | −0.026 | −0.043 | 0.834 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (9) TATO | 0.518 | 0.500 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.033 | −0.030 | 0.736 | 0.856 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (10) RG | −0.171 | −0.169 | 0.118 | 0.040 | 0.191 | 0.005 | −0.134 | −0.133 | −0.088 | 1.000 | |||||

| (11) SIZE | −0.304 | −0.265 | 0.230 | 0.312 | 0.154 | 0.150 | −0.040 | −0.224 | −0.189 | −0.121 | 1.000 | ||||

| (12) LEV | −0.253 | −0.079 | 0.141 | 0.141 | 0.133 | 0.094 | 0.031 | −0.317 | −0.195 | 0.039 | 0.282 | 1.000 | |||

| (13) CF | 0.124 | 0.125 | 0.002 | 0.008 | −0.009 | 0.004 | 0.163 | 0.161 | 0.162 | −0.072 | −0.029 | −0.055 | 1.000 | ||

| (14) GDP | −0.050 | −0.072 | −0.128 | −0.074 | −0.189 | −0.027 | −0.089 | −0.039 | −0.082 | 0.245 | 0.020 | −0.095 | −0.009 | 1.000 | |

| (15) IQ | −0.172 | −0.188 | 0.081 | 0.023 | 0.131 | 0.018 | −0.177 | −0.153 | −0.102 | 0.890 | −0.135 | 0.010 | −0.089 | 0.317 | 1.000 |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2.

- Source: Authors.

4.2 Dominant Market Logic

Table 6 provides the baseline regression results to test Hypothesis 1. The results of the first step estimation suggest a strong and significant negative relationship between ESG and TBQ at a 1% significance level (Panel 1). The magnitude of this nexus is economically meaningful. To put it into perspective, if the average ESG score increased by 10 units (a 24% increase) from 41.64 to 51.64, the TBQ would decrease from 1.84 to 1.78. In other words, if Saudi Arabia's ESG level were comparable to India's (increasing from 30.57 to 62.19), the TBQ would decrease from 1.83 to 1.64. Assuming a firm has total assets of $100 million and debt comprising 33.33% of its assets, the decrease in TBQ implies a 16.70% reduction in the firm's market capitalization.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | |

| ESG | −0.006*** | 0.001** | −0.006*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| E | −0.004*** | 0.001* | −0.004*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| S | −0.005*** | 0.001* | −0.005*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| G | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001 | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| ROE | 0.213 | 0.211 | 0.216 | 0.189 | ||||||||

| (0.210) | (0.209) | (0.209) | (0.210) | |||||||||

| TAT | 4.886*** | 4.872*** | 4.885*** | 4.883*** | 1.285*** | 1.285*** | 1.285*** | 1.285*** | 4.609*** | 4.597*** | 4.605*** | 4.638*** |

| (0.407) | (0.407) | (0.406) | (0.409) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.506) | (0.505) | (0.503) | (0.505) | |

| RG | 0.338*** | 0.326*** | 0.355*** | 0.391*** | −0.002 | −0.001 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.339*** | 0.327*** | 0.357*** | 0.392*** |

| (0.122) | (0.122) | (0.120) | (0.122) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.122) | (0.122) | (0.120) | (0.123) | |

| Size | −0.258*** | −0.256*** | −0.262*** | −0.287*** | 0.008*** | 0.008*** | 0.008*** | 0.008*** | −0.259*** | −0.258*** | −0.264*** | −0.289*** |

| (0.027) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.029) | |

| Lev | −0.210** | −0.193* | −0.207** | −0.164 | 0.019** | 0.019** | 0.019** | 0.019** | −0.211** | −0.194* | −0.208** | −0.165 |

| (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.105) | |

| CF | −0.084 | −0.105 | −0.075 | −0.081 | 0.032* | 0.033* | 0.033* | 0.032* | −0.089 | −0.111 | −0.081 | −0.086 |

| (0.238) | (0.239) | (0.237) | (0.238) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.238) | (0.238) | (0.237) | (0.238) | |

| GDP | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| IQ | −0.904*** | −0.905*** | −0.915*** | −0.975*** | −0.011 | −0.011 | −0.010 | −0.009 | −0.903*** | −0.904*** | −0.914*** | −0.975*** |

| (0.132) | (0.132) | (0.130) | (0.135) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.133) | (0.133) | (0.130) | (0.136) | |

| DCov | 0.095*** | 0.096*** | 0.096*** | 0.078*** | −0.005*** | −0.005*** | −0.005*** | −0.005*** | 0.096*** | 0.096*** | 0.097*** | 0.078*** |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | |

| Intercept | 7.210*** | 7.061*** | 7.279*** | 7.700*** | −0.172*** | −0.169*** | −0.176*** | −0.181*** | 7.248*** | 7.099*** | 7.318*** | 7.735*** |

| (0.594) | (0.597) | (0.597) | (0.616) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.598) | (0.601) | (0.601) | (0.620) | |

| Obs. | 5095 | 5102 | 5102 | 5102 | 5103 | 5110 | 5110 | 5110 | 5086 | 5093 | 5093 | 5093 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.376 | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.373 | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.377 | 0.377 | 0.376 | 0.374 |

| Period-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2. Panels 1–4 (Stage 1), 5–8 (Stage 2), and 9–12 (Stage 3) follow Equations (1), (2), and (3), respectively, employing random effect panel regression. The values in parentheses indicate the robust standard errors. ***, **, and *, respectively, represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%.

- Source: Authors.

This indicates that investors harbor a negative sentiment toward the ESG-related activities conducted by firms, as evidenced by their lowered expectations for firms' future cash flows. This aligns with shareholder theory and legitimacy theory but contrasts with RBV and stakeholder theories. According to shareholder theory, investors believe that an increased focus on ESG could potentially harm the fundamental performance of the firms, diverting them from choices that are most beneficial for shareholders' welfare. From a legitimacy theory perspective, investors perceive this as a negative signal, indicating underperformance in the company's financial bottom line.

These findings also hold for the individual dimensions of E, S, and G, as shown in Panels 2–4, respectively. However, some variations in the marginal effects of each dimension and their level of statistical significance are also observed. All three dimensions negatively impact firm value significantly at a 1% significance level, except for G. In terms of magnitude, the S dimension has the highest impact, followed by the E, whereas G is the least impactful element in the ESG framework. This discrepancy may arise because the G aspect is relatively more well established than the E and S, resulting in limited variations in practices across the firms in the sample. Investors appear to be less concerned about this aspect of ESG, as they perceive firms with reported ESG data, on average, as also performing well in G.

In the second stage of the estimation, we regress the firm's fundamental performance indicator, ROE, on ESG (Panels 5–8). Unlike TBQ, the results suggest a significant positive relationship between ROE and ESG at a 5% significance level. The magnitude of this relationship is also noteworthy. For instance, if the average ESG score increased by 10 units (a 24% increase) from 41.64 to 51.64, the average ROE would also have increased from 12.4% to 13.4%, representing a meaningful 1% improvement in the firm's profitability. To provide a different perspective, assuming Saudi Arabia's ESG level had been comparable to India's (increasing from 30.57 to 62.19), the aggregate profitability of Saudi Arabia's firms would have increased from 11.9% to 15.1%.

Unlike the first-stage results, this finding is inconsistent with shareholder and legitimacy theories but aligns with the RBV and stakeholder theory. It illustrates how adopting a more sustainable approach is beneficial for a company's fundamentals, as it becomes an important additional internal resource that can be utilized to sustain its competitive advantage in the market. While adhering to ESG principles may reduce the traditional investment universe, it opens new opportunities for managers to expand the company into new territories.

The above finding also holds for the three ESG dimensions. The impact of E, S, and G on ROE is positive, although only the impact of the E is statistically significant. This is consistent with our argument that the company's activities related to the ESG are at least not counterproductive to the firm's fundamental performance.

The diverging results of Equations (1) and (2) could not consistently be explained by the four main theories widely used in the literature above. The firm's market capitalization is determined by all available information, including its profitability. If ESG is positively associated with ROE, it should likewise have a positive impact on TBQ, and vice versa. However, our findings suggest the opposite.

To confirm this, we examine the mediating role of ROE on the ESG–firm value nexus. Panel 9 indicates that the adverse effect of ESG on market value remains unchanged even after incorporating ROE. Despite observing a strong relationship between ROE and TBQ, the impact of ESG on TBQ remains significant at a 1% level, with the same magnitude as observed in Panel 1. Consequently, ROE does not serve as a mediator in the relationship between ESG and TBQ, supporting our Hypothesis 1. The result also holds for the three separate ESG dimensions. They consistently mirror the findings of Panels 2–4, with ROE no longer significantly impacting the firm value.

This is where the institutional theory can contribute to offering a more consistent narrative. We attribute these results to the dominance of market logic in investors' perception of firms' ESG initiatives. The dominant market logic of investors hinders their recognition of the beneficial impact of embracing ESG activities within the company. Their expectations are adversely influenced more by the hypothetical possibility of a reduction in investment opportunities associated with adhering to ESG principles, rather than by the actual impact of ESG on the company's fundamental performance.

4.3 Temporality of Competing Institutional Logics

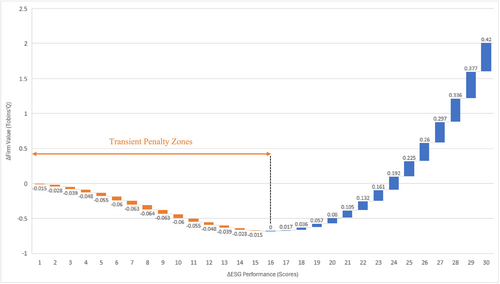

We then examine the temporality dimension of market dominance in corporate ESG observed above. Table 7 suggests a non-monotonic relationship between ESG performance and the firm's market value, consistent with our Hypothesis 2. Both the ESG scores and its squared term are significant at the 1% level. The differing signs of these coefficients indicate a U-shaped relationship, where investors initially penalize the market value of firms engaging in ESG activities. However, as ESG performance improves further, investors begin to appreciate the firm's involvement in ESG activities. The magnitude of the parameters is also economically plausible. Given that the average ESG score is 41.64, negative investor sentiment will persist until the score reaches 57.64, creating transient penalty zones. Beyond this point, investors' attitudes toward ESG become positive. This U-shaped relationship between ESG and firm value highlights the dynamic interactions between market and community logic. Initially, these logics are in competition, with the market serving as the dominant institutional order. However, a state of harmonious coexistence is achieved when reaches 16 (see Figure 1).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | |

| ESG | −0.016*** | 0.001 | −0.016*** | |||||||||

| (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.004) | ||||||||||

| ESG_SQ | 0.001*** | 0.001 | 0.001*** | |||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| E | −0.012*** | 0.001 | −0.012*** | |||||||||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.002) | ||||||||||

| E_SQ | 0.001*** | 0.001 | 0.001*** | |||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| S | −0.013*** | 0.001 | −0.013*** | |||||||||

| (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.003) | ||||||||||

| S_SQ | 0.001*** | −0.001 | 0.001*** | |||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| G | −0.007** | −0.001 | −0.007** | |||||||||

| (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.003) | ||||||||||

| G_SQ | 0.001* | 0.001 | 0.001* | |||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| ROE | 0.207 | 0.200 | 0.212 | 0.182 | ||||||||

| (0.211) | (0.210) | (0.209) | (0.211) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 7.369*** | 7.142*** | 7.361*** | 7.823*** | −0.171*** | −0.169*** | −0.177*** | −0.174*** | 7.406*** | 7.178*** | 7.399*** | 7.857*** |

| (0.593) | (0.598) | (0.596) | (0.613) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.028) | (0.597) | (0.602) | (0.600) | (0.618) | |

| Obs. | 5095 | 5102 | 5102 | 5102 | 5103 | 5110 | 5110 | 5110 | 5086 | 5093 | 5093 | 5093 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.374 | 0.379 | 0.379 | 0.373 | 0.604 | 0.605 | 0.605 | 0.605 | 0.381 | 0.381 | 0.383 | 0.374 |

| Firm-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Period-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2. Panels 1–4 (Stage 1), 5–8 (Stage 2), and 9–12 (Stage 3) follow Equations (1), (2), and (3), respectively, employing random effect panel regression. The values in parentheses indicate the robust standard errors. Control variables are not reported for brevity. ***, **, and *, respectively, represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%.

- Source: Authors.

The initial reaction of investors is negative as their market logic shapes their perception that many ESG activities are non-income-generating and harmful to the company. Previous research indicates that investors tend to perceive ESG initiatives as greenwashing and a mere marketing practice to cover companies' inability to generate financial profits (Treepongkaruna et al. 2024). They question whether higher ESG performance reflects a genuine commitment toward sustainability that will yield long-term benefits (Du 2015). The difficulty in measuring the immediate effects of ESG initiatives encourages investors to wait for sustained evidence of impact, contributing to a cautious approach to ESG-related valuations. This is why ESG activities may initially be dismissed as mere marketing efforts until companies consistently deliver concrete outcomes (Zharfpeykan 2021). This suggests that investors' initial attitudes toward ESG are influenced by hypothetical logic stemming from market order rather than by its actual financial impacts.

However, as evidence of ESG's positive influence on firm performance becomes more apparent, investor skepticism may gradually decrease (Barnett and Salomon 2012; Nollet et al. 2016). Once companies address greenwashing concerns and prove the value of ESG efforts, investors are more inclined to recognize and integrate these positive effects into firm valuations, ultimately moving beyond the initial “penalty zones.”

To ensure the robustness of the transient penalty zones in the interaction between market and community logics within the ESG performance–firm value nexus, we employ Lind and Mehlum's (2010) methodology on the first- and third-stage regressions presented in Table 8. This method is not applied to the second-stage regression, as no evidence of nonlinearity was identified (see Table 7). Our findings confirm the presence of a U-shaped relationship between ESG performance (E/S/G dimensions) and Tobin's Q. First, the extremum points and Fieller's (1954) confidence intervals for ESG (E/S/G) largely fall within the observed data range. For example, the Fieller confidence interval for turning point Environmental dimension ([4.5, 8.5]) is well above its minimum observed value of zero. Second, the overall Sasabuchi (1980) test is significant at the 1% level in the first- and third-stage regressions, rejecting the null hypothesis of no nonlinear relationship between ESG (E/S/G) and TBQ. Finally, the lower bound slope ( ) and upper bound slope ( ) are consistently negative and positive, respectively, across all models in the first- and third-stage regressions, reinforcing the evidence of a U-shaped relationship between the variables. These results collectively support our hypothesis regarding the temporality of institutional logics in ESG practices within the Global South.

| Stage 1 | Stage 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: TBQ | ESG | E | S | G | ESG | E | S | G | ||

| ESG ( ) | −0.016 | −0.012 | −0.013 | −0.007 | −0.016 | −0.012 | −0.013 | −0.007 | ||

| ESG_SQ ( ) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Extremum point | 8.000 | 6.000 | 6.500 | 3.500 | 8.000 | 6.000 | 6.500 | 3.500 | ||

| Lower extr. (Fieller, 95%) | 4.500 | 4.500 | 4.000 | 0.500 | 4.500 | 4.500 | 4.000 | 0.500 | ||

| Upper extr. (Fieller, 95%) | 12.500 | 8.500 | 10.000 | 6.500 | 12.500 | 8.500 | 10.000 | 6.500 | ||

| Sasabuchi test p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Lower bound slope at ( ) | −0.015 | −0.012 | −0.012 | −0.007 | −0.015 | −0.012 | −0.012 | −0.007 | ||

| Upper bound slope at ( ) | 0.172 | 0.186 | 0.183 | 0.188 | 0.172 | 0.186 | 0.183 | 0.188 | ||

- Note: This table applies Lind and Mehlum's (2010) methodology to parametrically test for the presence of a U-shaped relationship between ESG (E/S/G dimensions) and market value (TBQ). Stage 2 regression is excluded from the analysis due to the lack of evidence supporting a quadratic relationship, as indicated in Table 7. In this context, the extremum point represents the lowest turning point in the relationship between ESG (E/S/G) and TBQ. The confidence interval for the extremum is computed using Fieller's (1954) method. The Sasabuchi test p value evaluates the null hypothesis ( ) that no nonlinear relationship exists between ESG and TBQ, as proposed by Sasabuchi (1980). The presence of a U-shaped relationship is confirmed if the following three conditions are met: (i) The turning point lies within the interval ; (ii) the overall Sasabuchi test is statistically significant; and (iii) the lower bound slope is negative, whereas the upper bound slope is positive.

4.4 Robustness Checks

Our findings are robust to variations in the (i) sample, (ii) period, (iii) measurements of firm value and fundamental performance, and (iv) endogeneity problem. For the sake of brevity, we present only the robustness test results related to the endogeneity problem, although the other robustness checks are available in Appendix B.

We address potential endogeneity in our models by employing the IV 2-SLS method. We use the mean ESG (and its dimensions) by industry and the initial ESG (and its dimensions) level as IVs in Table 9a (first stage), following the approach of El Ghoul et al. (2011) and Benlemlih and Bitar (2018). These studies provide evidence that these IVs are exogenous to factors influencing the contemporaneous (current) ESG score. The initial ESG score (In_ESG) is considered exogenous because it reflects past ESG performance and is unlikely to be affected by current unobserved factors driving firm performance. The sector-level ESG score (Mean_ESG) captures external ESG trends at the industry level, rather than firm-specific dynamics, making it less likely to be influenced by individual firm performance. Subsequently, we utilize the fitted values of our IVs in Table 9b (second stage) and document consistent results with the baseline estimations.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | E | S | G | |

| Mean_ESG (E/S/G) | 0.467 | |||

| (0.371) | ||||

| Mean_E | 2.017*** | |||

| (0.560) | ||||

| Mean_S | 0.673 | |||

| (0.600) | ||||

| Mean_G | 0.274 | |||

| (0.606) | ||||

| In_ESG (E/S/G) | 0.778*** | |||

| (0.017) | ||||

| In_E | 0.897*** | |||

| (0.026) | ||||

| In_S | 0.939*** | |||

| (0.023) | ||||

| In_G | 0.601*** | |||

| (0.027) | ||||

| Intercept | −81.951*** | −233.231*** | −99.676*** | −36.721 |

| (16.041) | (25.034) | (26.140) | (26.445) | |

| Obs. | 5111 | 5111 | 5111 | 5111 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.577 | 0.481 | 0.524 | 0.237 |

| Firm-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Period-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2. The instrumental variables are the mean of ESG score by sector (Mean_ESG) and the initial level of ESG by the company (In_ESG) following El Ghoul et al. (2011) and Benlemlih and Bitar (2018). The values in parentheses indicate the robust standard errors. Control variables are not reported for brevity. ***, **, and *, respectively, represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%.

- Source: Authors.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | |

| ESG | −0.005** | 0.000 | −0.005** | |||||||||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.002) | ||||||||||

| E | −0.005** | 0.000 | −0.005** | |||||||||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.002) | ||||||||||

| S | −0.004** | 0.000 | −0.004** | |||||||||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.002) | ||||||||||

| G | −0.007** | 0.000 | −0.007** | |||||||||

| (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.003) | ||||||||||

| ROE | 0.186 | 0.186 | 0.186 | 0.186 | ||||||||

| (0.210) | (0.210) | (0.210) | (0.210) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 7.457*** | 7.118*** | 7.475*** | 7.614*** | −0.183*** | −0.183*** | −0.183*** | −0.182*** | 7.490*** | 7.149*** | 7.508*** | 7.649*** |

| (0.614) | (0.639) | (0.614) | (0.614) | (0.029) | (0.032) | (0.029) | (0.028) | (0.619) | (0.645) | (0.619) | (0.619) | |

| Obs. | 5095 | 5095 | 5095 | 5095 | 5103 | 5103 | 5103 | 5103 | 5086 | 5086 | 5086 | 5086 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.371 | 0.371 | 0.371 | 0.371 | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.372 | 0.372 | 0.372 | 0.372 |

| Firm-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Period-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: Pre stands for fitted values of ESG and its three dimensions obtained from the first stage of regression, where the instrumental variables are the mean of ESG score by sector and the initial level of ESG by the company following El Ghoul et al. (2011) and Benlemlih and Bitar (2018). All panels control for firm-specific, region, and industry. Panels 1–4 (Stage 1), 5–8 (Stage 2), and 9–12 (Stage 3) follow Equations (1), (2), and (3), respectively. The values in parentheses indicate the robust standard errors. Control variables are not reported for brevity. ***, **, and *, respectively, represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%.

- Source: Authors.

5 Discussion

Our finding that market logic continues to dominate the corporate ESG practice in the Global South is consistent with the previous literature, including Ko et al. (2021) on business strategy, Silva and Nunes (2022) on supply chain, Asutay et al. (2023) on capital markets, and Siefkes et al. (2024) on venture capital. However, our findings go the extra mile by proving the temporality dimension of the dominance of the market logic.

Our results suggest that a firm's sustainability performance positively impacts its fundamentals or, at the very least, does not adversely affect financial performance, consistent with findings by Qureshi et al. (2021) and Shin et al. (2023). Despite these positive effects, however, investors continue to penalize ESG strategies by discounting firm value, as documented by Di Giuli and Kostovetsky (2014) and Behl et al. (2022). This suggests a lack of harmony between the coexisting market and community logics within corporate ESG practices.

Our further analysis suggests that this competing logic is, in fact, dynamic, as anticipated by Darnall et al. (2024) and Gümüşay et al. (2024). We show that in the long run, the convergence of market and community logics in the corporate ESG is feasible. The initial negative ESG performance–firm value relationship turns positive as investors verify that the firms' ESG initiatives are driven by genuine sustainability goals rather than greenwashing. This shift is evidenced as the financial benefits of ESG initiatives become more apparent in the longer term. As a result, investors increasingly view firms' ESG strategies as value-enhancing, aligning with Connelly et al. (2010), Nollet et al. (2016), and Oehmichen et al. (2021).

This shift may also reflect an evolution of the manager's logic. Managers' attitudes toward ESG initiatives are also influenced by both internal and external factors. Internally, CEOs' personal agency, shaped by their moral foundations, influences their worldview and approach to corporate ESG (Ng et al. 2024). Externally, the pressures come not only from shareholders but also from customers (Boh et al. 2020), governments (Arvidsson and Dumay 2022), creditors (Yiu et al. 2019), and communities (Kacperczyk 2009). Burke (2022) suggests that shifting norms at the board level have led CEOs to become increasingly concerned about stakeholders' negative perceptions related to ESG misconduct, which could result in their dismissal. This pressure from non-shareholder stakeholders drives managers to prioritize non-pecuniary reputational concerns, thereby accelerating their adoption of community logic (Colak et al. 2024).

This shift is consistent with the findings from longitudinal surveys conducted by the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), summarized in Appendix C. In the past, managers primarily engaged in ESG activities to enhance social signaling (UNGC 2007, 2010, 2013; Deng et al. 2025). Recently, however, managers increasingly view sustainability as aligning with the company's goal of gaining market power through innovation (UNGC 2019, 2023; Cahyono et al. 2024). This change is evident in survey data, where 98% of CEOs in 2023 reported that advancing sustainability is a key part of their role, up from 83% in 2013 (UNGC 2023). Agreement levels have also deepened: In 2013, only 19% of CEOs strongly agreed with this responsibility, compared to 72% in 2023 (UNGC 2023). Such shifts may reduce managerial short-termism, encouraging companies to embed ESG initiatives into sustainable business strategies rather than engaging in greenwashing. This trend could ultimately help harmonize market and community logic in an optimal equilibrium.

6 Conclusion

We conclude that market logic remains the dominant institutional order shaping how corporations in emerging economies pursue societal legitimacy through ESG initiatives. Although there is strong evidence that ESG efforts do not compromise firms' financial performance and may even enhance it, shareholders frequently penalize these efforts by lowering firms' valuations, driven by the preconceived notion of a trade-off between social and environmental performance and financial returns. Nevertheless, as Gümüşay et al. (2024) highlight, the institutional logics governing corporate ESG are influenced by both contextual and temporal factors, enabling dynamic interactions between market and community logics. Managers are increasingly aligning with community logics, striving to balance the interests of shareholders with those of other stakeholders. At the same time, investors' initial negative perceptions of ESG activities are also temporary. They tend to appreciate ESG initiatives once investors can verify such strategies are not merely greenwashing and their positive effects on profitability become evident. This makes the coexistence between community and market logics in corporate ESG feasible, especially in the long run, consistent with Greenwood et al. (2011).

Our study contributes to the literature by demonstrating how institutional theory can bridge the theoretical gaps left by the overly simplistic application of the agency framework in corporate sustainability, much like it has in other areas of business (Cheung et al. 2020; Ko et al. 2021; Silva and Nunes 2022; Siefkes et al. 2024). We deepen the understanding of the interaction between conflicting institutional logics by highlighting the dominant role of market logic in business settings (Asutay et al. 2023; Jatmiko et al. 2025). Unlike prior research, however, we expand this analysis by focusing on the Global South and elucidating the temporal dynamics of institutional logics within corporate ESG contexts, showing how businesses engage with non-market (community) logics in their pursuit of societal legitimacy (Darnall et al. 2024; Gümüşay et al. 2024).

From a business strategy point of view, our contribution lies in deepening our understanding of the contextual and temporal dynamics within the institutional logics that shape corporate sustainability. This understanding is crucial for integrating the diverse logics of various stakeholders into a coherent equilibrium.

Our findings imply that managers should communicate compelling narratives and provide concrete evidence to illustrate how incorporating social and environmental pillars into business strategies can drive LTVC and sustainably enhance the firm's bottom line. Establishing transparent and robust communication channels is essential for effectively conveying the multidimensional impacts of ESG to all stakeholders. Moreover, a standardized framework for sustainability disclosure is necessary to mitigate the risk of greenwashing and maintain investor confidence in firms' ESG initiatives. These measures can help eliminate—or at least minimize—transient penalty zones, ensuring that the positive impact of ESG is more directly reflected in firm valuation.

Several limitations could be addressed in future research. This study focuses on the aggregate behavior of investors, particularly those following traditional and classic ESG investment strategies, rather than socially responsible or impact investors. Although this approach aligns with prior literature, future studies could gain valuable insights by exploring the heterogeneity among different types of investors (e.g., institutional vs. retail) and managers (e.g., multinational vs. domestic corporations). Additionally, financial corporations were excluded from our analysis due to their unique characteristics in the principal–agent context, which merit separate investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Associate Editor Andreas Stephan, the three anonymous referees, Dalal Aassouli, Mehmet Asutay, Celia Aviana, Hisham Farag, Mingyi Hung, Effie Kesidou, Amirul A. Muhamat, Muhammad A. Nasir, Jaafar Pyeman, Riikka Sarala, Timothy Werner, and participants at the 7th Ethical and Sustainable Finance Conference 2024, University of Leeds, UK; the 4th ASFAAG Annual Conference 2024, Athens, Greece; the Gulf Research Meeting 2023, University of Cambridge, UK; and the FBM UiTM International Forum Series 4 2023, Malaysia, for their valuable comments and feedback on the previous versions of this paper.

Appendix A: Spectrum of Investors' Logics

| Dimension | Traditional investor | Classic ESG investor | Socially responsible investor | Impact investor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant institutional order | Market | Market | Community with market influence | Community |

| Investor value and preference | A sole financial value | Financial value with non-pecuniary motivations | Primarily driven by non-pecuniary motivation | Focus mainly on delivering environmental and social outcomes |

| Strategy | Risk-adjusted return optimization, greater than market return | The majority seeks greater than market return even though a few agents welcome slightly below expectation | Some are willing to accept “close-to-market” suboptimal risk-adjusted return in exchange for non-pecuniary outcomes | Some are willing to accept a suboptimal risk-adjusted return, but others constrained by the market benchmark as a minimum value |

Appendix B: Robustness Checks

Table B1 controls for countries with a small number of firms, such as Egypt, Hungary, and India, to mitigate potential biases arising from a limited sample size. Here, we observe findings that strongly align with our results, indicating that investors temporarily penalize firms committed to ESG principles, despite the improved financial performance associated with such a commitment.

Table B2 excludes the periods of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 and 2021) due to potential distinct characteristics in the fundamental performance and value of firms, notwithstanding the baseline regression already accounting for them using the COVID-19 dummy. Once again, we observe consistent findings. An interesting result emerges where G is not priced by investors during the normal period of the sample. This finding supports our argument that G is a well-practiced aspect by most companies in our sample, leading investors to overlook it during periods of normal economic conditions.

Table B3 modifies the proxy for the market value of the firm from TBQ to PBV, whereas Table B4 substitutes the firm's performance proxy from ROE to ROA to address potential measurement biases in the variables of interest. PBV offers an alternative measure for the market value of the firm by considering the historical net worth of the company, whereas TBQ focuses on assets' replacement costs. On the other hand, ROA provides a measure of the firm fundamental performance attributed not only to equity holders, as in the case of ROE, but also to bondholders. Overall, our results are robust to these proxy changes. Despite the strong influence of ROE on PBV, our conclusion remains unchanged as it fails to diminish the impact of ESG (and its dimensions) on PBV. Similarly, the role of ROA in the relationship between ESG (and its dimensions) and TBQ remains consistent.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | |

| ESG | −0.006*** | 0.001*** | −0.006*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| E | −0.004*** | 0.001** | −0.004*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| S | −0.005*** | 0.001** | −0.005*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| G | −0.001 | 0.001* | −0.001 | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| ROE | 0.232 | 0.224 | 0.236 | 0.199 | ||||||||

| (0.215) | (0.214) | (0.214) | (0.215) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 7.646*** | 7.499*** | 7.727*** | 8.142*** | −0.183*** | −0.181*** | −0.188*** | −0.193*** | 7.690*** | 7.542*** | 7.773*** | 8.181*** |

| (0.578) | (0.580) | (0.580) | (0.600) | (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.582) | (0.584) | (0.585) | (0.605) | |

| Obs. | 4988 | 4995 | 4995 | 4995 | 4979 | 4986 | 4986 | 4986 | 4979 | 4986 | 4986 | 4986 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.383 | 0.382 | 0.382 | 0.380 | 0.609 | 0.609 | 0.609 | 0.609 | 0.384 | 0.383 | 0.383 | 0.381 |

| Firm-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Period-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2. Panels 1–4 (Stage 1), 5–8 (Stage 2), and 9–12 (Stage 3) follow Equations (1), (2), and (3), respectively, employing random effect panel regression. The values in parentheses indicate the robust standard errors. Control variables are not reported for brevity. ***, **, and *, respectively, represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%.

- Source: Authors.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | |

| ESG | −0.005*** | 0.000** | −0.005*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| E | −0.004*** | 0.000** | −0.004*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| S | −0.005*** | 0.000** | −0.005*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| G | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| ROE | 0.186 | 0.184 | 0.192 | 0.140 | ||||||||

| (0.239) | (0.238) | (0.238) | (0.238) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 6.354*** | 6.224*** | 6.415*** | 6.756*** | −0.148*** | −0.144*** | −0.153*** | −0.158*** | 6.383*** | 6.253*** | 6.446*** | 6.779*** |

| (0.547) | (0.552) | (0.548) | (0.565) | (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.549) | (0.553) | (0.550) | (0.567) | |

| Obs. | 3412 | 3417 | 3417 | 3417 | 3422 | 3427 | 3427 | 3427 | 3405 | 3410 | 3410 | 3410 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.396 | 0.397 | 0.395 | 0.397 | 0.603 | 0.603 | 0.603 | 0.602 | 0.398 | 0.399 | 0.397 | 0.399 |

| Firm-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Period-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2. Panels 1–4 (Stage 1), 5–8 (Stage 2), and 9–12 (Stage 3) follow Equations (1), (2), and (3), respectively, employing random effect panel regression. The values in parentheses indicate the robust standard errors. Control variables are not reported for brevity. ***, **, and *, respectively, represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%.

- Source: Author.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBV | PBV | PBV | PBV | ROE | ROE | ROE | ROE | PBV | PBV | PBV | PBV | |

| ESG | −0.007*** | 0.000** | −0.008*** | |||||||||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.002) | ||||||||||

| E | −0.005*** | 0.000* | −0.005*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| S | −0.006*** | 0.000* | −0.006*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| G | −0.003** | 0.000 | −0.003** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| ROE | 2.470*** | 2.483*** | 2.487*** | 2.464*** | ||||||||

| (0.485) | (0.484) | (0.484) | (0.485) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 7.770*** | 7.607*** | 7.844*** | 8.409*** | −0.172*** | −0.169*** | −0.176*** | −0.181*** | 8.210*** | 8.047*** | 8.303*** | 8.874*** |

| (1.042) | (1.034) | (1.059) | (1.077) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (1.040) | (1.035) | (1.057) | (1.077) | |

| Obs. | 5086 | 5093 | 5093 | 5093 | 5103 | 5110 | 5110 | 5110 | 5080 | 5087 | 5087 | 5087 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.385 | 0.386 | 0.383 | 0.390 | 0.604 | 0.605 | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.391 | 0.392 | 0.389 | 0.396 |

| Firm-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Period-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-specific | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: The variables definition follows Table 2. Panels 1–4 (Stage 1), 5–8 (Stage 2), and 9–12 (Stage 3) follow Equations (1), (2), and (3), respectively, employing random effect panel regression. The values in parentheses indicate the robust standard errors. Control variables are not reported for brevity. ***, **, and *, respectively, represent significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%.

- Source: Authors.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | ROA | ROA | ROA | ROA | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | TBQ | |

| ESG | −0.006*** | −0.000 | −0.006*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| E | −0.004*** | −0.000 | −0.004*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| S | −0.005*** | −0.000 | −0.005*** | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| G | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| ROA | 2.029*** | 2.035*** | 2.028*** | 2.034*** | ||||||||

| (0.487) | (0.485) | (0.483) | (0.489) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 7.205*** | 7.055*** | 7.274*** | 7.694*** | 0.034*** | 0.034*** | 0.034*** | 0.035*** | 7.078*** | 6.925*** | 7.146*** | 7.562*** |