Corporate Governance Practices and Circular Supply Chain Management Relationship: Eco-Innovation Leadership and the Perceived Urgency Paradox Based on a Three-Way Interaction Model

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

The accelerating decline in global circularity and fragmented implementation of Circular Supply Chain Management (CIRSCM), particularly in developing economies, highlights the necessity for enhanced behavioural and institutional drivers. This study examines the influence of corporate governance (CORPGOV) on CIRSCM, with eco-innovation leadership (EIL) serving as both a mediating and moderating mechanism and perceived urgency for circularity acting as a boundary condition. Utilising an integrative framework, the Stewardship–Behavioural Alignment Theory (SBAT), this research integrates the Stewardship Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour to elucidate how governance systems are translated into circular outcomes through leadership behaviour and contextual urgency. Data were collected from 381 manufacturing firms in Ghana through a structured survey targeting top and mid-level managers. A hybrid analytical approach employing structural equation modelling (SEM) and PROCESS macro regression was used to test the hypothesised relationships. The findings confirm a positive and significant relationship between CORPGOV and CIRSCM, establishing that EIL partially mediates this link. Furthermore, EIL significantly moderates the CORPGOV–CIRSCM relationship, and this moderating effect is amplified under high levels of perceived urgency. More importantly, financial slack should not be viewed merely as excess capacity; rather, it should function as a strategic buffer and resource reserve that enables firms operating under financial constraints to mitigate risk and pursue circular objectives. Industry-specific analyses reveal heterogeneous effects, with plastic firms demonstrating stronger governance–circularity alignment, while wood-processing firms exhibit negative moderation, highlighting sectoral divergence in circular readiness. Managerial experience was found to be non-significant, indicating that experience rooted in legacy linear models may not facilitate circular transition. This study contributes to the theory by conceptualising governance as a behavioural enabler rather than as a structural determinant.

1 Introduction

The rapid advancement of global industrialisation, alongside sustained reliance on non-renewable energy sources, has led to an increase in solid waste production and exacerbated climate change. These challenges highlight the urgent need for systemic regenerative strategies that emphasise resource efficiency and ecological resilience. Circular Supply Chain Management (CIRSCM) has emerged as a pivotal driver of operational sustainability and competitive advantage (Carissimi et al. 2024). The shift from a linear to circular economy is no longer merely aspirational; it is a strategic necessity, particularly for manufacturing sectors in developing economies facing environmental degradation and fluctuating stakeholder demands (Salvioni and Almici 2020).

Despite the proliferation of recycling initiatives, recent data indicate a troubling decline in global circularity between 2021 and 2023, while remanufacturing constitutes only 1.9% of new production in Europe (Sakao et al. 2024). Yang et al. (2023) emphasised the transformative potential of circularity to reduce carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 and support carbon neutrality goals by 2050. However, the implementation of CIRSCM remains fragmented, particularly in the Global South, where empirical evidence of effective mechanisms is limited (Ahakwa et al. 2023; Ahmed et al. 2022). CIRSCM integrates forward and reverse logistics within a value-creation framework that extends product lifecycles and promotes the regenerative flows of materials and energy (Farooque et al. 2019). However, the strategic execution of circular supply chains is hindered by conceptual ambiguity and stakeholder misalignment. Munaro and Tavares (2023) observed that limited understanding and conflicting interests impede collaborative efforts to achieve circularity. Similarly, Mayer et al. (2019) note that stakeholders interpret circularity from different perspectives, aligning the concept with narrow organizational priorities. This interpretive fragmentation undermines coherence, dilutes accountability, and ultimately weakens circularity performance. Further complicating these challenges is the overly technological framing of circularity strategies, with insufficient exploration of organizational and institutional transformation mechanisms (Henrysson and Nuur 2021). Iacovidou et al. (2021) stressed the importance of considering the contextual environments in which circularity was implemented. However, significant empirical gaps persist in understanding how socioeconomic, regulatory, and industrial dynamics influence the design and outcomes of CIRSCM, particularly in developing countries characterised by fragile institutions, fragmented policies, and diverse stakeholder configurations.

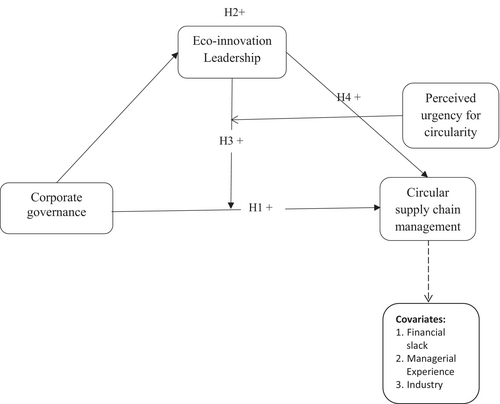

This research explores how corporate governance is translated into circular supply chain outcomes through eco-innovation leadership while also considering the impact of perceived urgency on this dynamic. Eco-innovation leadership is conceptualised to fulfil a dual function: (1) as a mediator, it elucidates the behavioural mechanism through which corporate governance is translated into circular supply chain outcomes; and (2) as a moderator, it influences the strength of this relationship contingent upon the ecological orientation of leadership (e.g., Bodet 2008). To achieve this, a multilevel framework is proposed, grounded on the Stewardship Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Corporate Governance (CORPGOV), a critical yet underexplored enabler in this discourse, provides strategic oversight, transparency, and accountability mechanisms that are essential for aligning firms with circularity goals (Sari 2023; Yolcu 2025). While previous studies have linked CORPGOV with broader environmental performance and sustainability reporting, its direct influence on CIRSCM in developing economies remains largely unexamined (Boakye et al. 2025; Chigwedere et al. 2022). This omission is significant, given the governance vulnerabilities in these regions, ranging from weak enforcement to low stakeholder trust, which potentially distort or dilute sustainability objectives.

Central to this relationship is eco-innovation leadership (EIL), which embodies a leader's dedication (willingness and readiness) to promoting environmentally sustainable innovations. While effective corporate governance (CORPGOV) articulates ethical norms and strategic direction, without eco-innovative leadership to implement these norms, governance structures may remain ineffective. Eco-Innovation Leadership (EIL) is conceptualised as a leadership disposition characterised by internalised ecological values, strategic foresight, and proactive commitment to integrating sustainability-driven innovation. It functions as a behavioural conduit through which corporate governance (CORPGOV) principles are operationalised within circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) practices, encompassing lifecycle extension, waste valorisation, and regenerative design (Sohmen 2015; Edwards 2000). EIL facilitates this translation by promoting an innovation-oriented organizational culture, aligning internal capabilities with ecological imperatives, and reconfiguring resource allocation to favour circularity. However, in the institutional landscapes of developing economies, which are often marked by regulatory fragmentation and weak enforcement, leadership alone may be insufficient to catalyse systemic change.

In such contexts, the perception of urgency for circularity (PURGENCY) has emerged as a critical boundary condition that influences the extent to which eco-innovation leadership can activate governance mandates. Grounded in the crisis cognition and environmental sensemaking literature (Hellier et al. 2002), PURGENCY reflects an actor's interpretation of ecological and market signals as necessitating immediate, non-incremental action. While existing models tend to isolate behavioural or structural drivers, they often overlook how urgency perceptions condition the behavioural elasticity of leadership in enacting governance intentions. Therefore, this study positions PURGENCY not merely as a contextual backdrop but also as a catalytic moderator, amplifying the moderating role of EIL in the CORPGOV–CIRSCM relationship. PURGENCY is described as a situational cognitive-affective trigger that enables decision makers to interpret environmental and institutional signals as requiring immediate and non-deferrable circular action.

This study addresses these interconnected theoretical and practical gaps by proposing a multilevel conceptual model grounded on the Stewardship Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The Stewardship Theory reinterprets CORPGOV as a normative system that positions executives as stewards of societal and environmental value, rather than mere agents of shareholder interests (Davis et al. 1997). The TPB elucidates EIL as an outcome of pro-environmental attitudes, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norms (Ajzen 1991), thereby clarifying how leadership intentions shape the enactment of governance principles within CIRSCM strategies. By integrating these perspectives, this study addresses the following research questions. RQ1: To what extent does corporate governance influence circular supply chain management in developing economies? RQ2: How does eco-innovation leadership mediate the relationship between governance and circular supply chains? RQ3: Does EIL strengthen the impact of governance on CIRSCM at different intensity levels? RQ4: How does the perceived urgency for circularity shape the conditional influence of EIL on the CORPGOV-CIRSCM link?

By consolidating governance, leadership, and urgency within a unified explanatory framework, this study contributes both theoretical clarity and actionable insights into the organizational dynamics underpinning circular transitions in emerging markets. To this end, this study investigates the dual function of eco-innovation leadership in mediating and moderating the relationship between corporate governance and circular supply chains, particularly under varying levels of perceived urgency. This research contributes to the literature on circularity by introducing eco-innovation leadership (EIL) as a construct with dual functions: serving as a behavioural conduit (mediator) and a strategic moderator within the corporate governance–circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) framework. This reconceptualisation not only provides a novel empirical examination of the stewardship–behavioural alignment theory (SBAT) but also highlights a leadership–urgency paradox, demonstrating that the influence of EIL is contingent upon the perceived urgency of circularity. Empirically, this study addresses calls for contextual diversity by presenting evidence from Ghana's manufacturing sector, an underexplored context in which circular ambitions intersect institutional constraints. Practically, it offers actionable guidance by suggesting that firms integrate ecological innovation capabilities into leadership development, utilising tools such as eco-leadership scorecards and sustainability capability diagnostics to align governance intentions with operational outcomes.

This study, which also extends Halidu et al. (2025), is part of an extensive research programme that examines the complex dynamics of circular governance in resource-limited settings. While this study and Halidu et al. (2025) are based on the same empirical dataset of 381 Ghanaian manufacturing firms, they have been independently theorised and analytically delineated to address the distinct aspects of the circular transition challenge. This study theorises that corporate governance (CORPGOV) influences circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) through the dual role of eco-innovation leadership (EIL) as both a mediator and moderator, with perceived urgency for circularity serving as a boundary condition shaping the effectiveness of this leadership dynamic. It advances the stewardship-behavioural alignment theory (SBAT) by demonstrating how urgency thresholds activate governance through leadership behaviour to catalyse systemic circular change. In contrast, Halidu et al. (2025) extends Stewardship Theory by focusing on culture as the locus of behavioural alignment, positing eco-adaptive organizational culture (EAOC) as the primary mediator that channels the influence of corporate governance (CORPGOV) into circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) outcomes.

The present study further conceptualises eco-innovation leadership (EIL) and perceived urgency for circularity as interactive boundary conditions that shape the emergence of internal cultural readiness. By foregrounding the leadership behaviour-urgency paradox, this study demonstrates that even well-intentioned stewardship initiatives prove ineffective unless driven by a compelling sense of urgency that can transform leadership signals into sustained cultural integration of circularity. Together, the present study and Halidu et al. (2025) offer complementary yet theoretically distinct extensions of the Stewardship Theory: the present study elucidates how urgency-amplified leadership mobilisation transforms governance into circular action, while Halidu et al. (2025) demonstrates how the cultural institutionalisation of stewardship norms is critical for sustaining such transformation. This dual-theory contribution deepens the understanding of how governance systems in emerging economies must orchestrate leadership behaviour, cultural congruence, and external urgency signals to overcome structural inertia and promote systemic circularity.

2 Theoretical Perspective and Hypotheses Development

2.1 The Link Between Corporate Governance and Circular Supply Chain Management

The Stewardship Theory reimagines organizational leaders as stewards motivated to advance the collective good of the firm and stakeholders rather than self-interested agents (Chrisman 2019). This perspective emphasises psychological ownership and long-term orientation, whereby leaders prioritise sustainable value creation over personal gain (Keay 2017). Unlike agency theory's assumptions, stewardship theory shows that directors align naturally with the goals of resilience and accountability when supported by appropriate governance structures. This alignment is crucial today, as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) pressures along with environmental risks have redefined corporate purposes. Seun et al. (2024) suggest that evolving corporate governance requires theoretical frameworks that embrace ecological responsibility as a core organizational mission. The Stewardship Theory provides an ideal lens for understanding how governance drives sustainability practices, such as circular supply chain management (CIRSCM), requiring long-term strategy and innovation. Stewardship-oriented governance creates conditions of accountability and trust, in which circular initiatives thrive. Applying stewardship theory to corporate governance offers a framework for examining sustainable transitions, particularly in resource-constrained manufacturing sectors of developing economies. In this context, organisations governed by boards with stewardship orientation are more inclined to integrate sustainability principles into their fundamental operations, thereby cultivating the cultural and strategic conditions essential for CIRSCM. Based on this backdrop, this study hypothesises that:

H1.CORPGOV has a direct and positive effect on CIRSCM.

2.2 The Mediating and Moderating Role of Eco-Innovation Leadership

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen 1991) asserts that behavioural intentions are derived from attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control elements that influence environmentally responsive actions through individual belief systems and social influence (Hagger and Hamilton 2025). When integrated with the Stewardship Theory, which emphasises the intrinsic motivation of organizational actors to pursue collective, long-term objectives, TPB offers a behaviourally grounded extension to structurally embedded governance logic. This synthesis provides a dual-level perspective through which the translation of corporate governance (CORPGOV) principles into circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) practices can be understood more comprehensively.

Emerging from this theoretical confluence is the Stewardship-Behavioural Alignment theory (SBAT), a novel framework that amalgamates institutional governance structures, leadership intentionality, and contextual pressures. The SBAT posits that effective circular transformation is not merely a function of governance design, but rather of its alignment with leaders' behavioural orientation towards sustainability. Eco-innovation leadership, characterised by proactive advocacy for ecological values, investment in regenerative technologies, and responsiveness to sustainability drivers, serves as a central mechanism through which governance principles are operationalised in practise. Accordingly, this study hypothesises that:

H2.Eco-innovation leadership acts as an intermediary in the relationship between corporate governance and circular supply chain management.

Furthermore, recent scholarship emphasises that corporate governance, while crucial, does not inherently lead to transformation unless it is activated through leadership that is sensitive to context. Although some studies (e.g., Rashid 2018) have questioned the substantive impact of governance structures, highlighting their occasional symbolic adoption, emerging perspectives (Ledi et al. 2025) affirm the normative potential of governance in shaping ethical conduct and aligning strategies with sustainability goals. However, the effectiveness of such governance in driving sustainability outcomes depends on its alignment with the leadership orientation. Within this evolving discourse, eco-innovation leadership emerges not merely as a behavioural style but also as a contextual amplifier- a force that dynamically influences how corporate governance affects operational sustainability.

Leaders who internalise ecological values and exhibit a forward-looking, innovation-driven mindset can elevate governance frameworks from compliance-focused instruments to engines of systemic circularity. Such leaders foster an organizational climate that is receptive to closed-loop thinking, technological regeneration, and sustainability integration across the supply chain. Drawing on the Stewardship–Behavioural Alignment Theory (SBAT), we conceptualise eco-innovation leadership as a contingent enabler, moderating the CORGOV–CIRSCM relationship by either reinforcing or diminishing its strength based on the depth of ecological commitment and strategic foresight embedded in leadership practices. In firms with pronounced eco-innovation leadership, corporate governance is more likely to translate into actionable circular supply chain strategies. Conversely, well-structured governance may struggle to yield substantive circular outcomes under low levels of eco-innovation leadership. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

H3.Eco-innovation leadership positively moderates the relationship between corporate governance and circular supply chain management such that this relationship is significantly stronger when eco-innovation leadership is high.

2.3 Perceived Urgency for Circularity as a Boundary Condition to Eco-Innovation Leadership

Establishing a compelling sense of urgency is fundamental for catalysing meaningful transformation, as Kotter's (1996) seminal change model identifies it as an indispensable first step in navigating systemic transitions (Mitcheltree 2023). In the context of advancing circular supply chain management (CIRSCM), the perceived urgency for circularity, thus, the organizational awareness of escalating ecological constraints and stakeholder pressures functions as a boundary condition that shapes the efficacy of leadership dynamics. Integrating Kotter's urgency logic with the Stewardship–Behavioral Alignment Theory (SBAT) enriches our understanding of this conditionality. This suggests that eco-innovation leadership's moderating role is not fixed but situationally elastic, amplified or muted by the contextual salience of circularity imperatives. Thus, urgency operates as a psychological trigger (Elliott et al. 2024) that mobilises both the intentionality of eco-innovative leaders and the institutional traction of corporate governance, thereby synchronising strategic orientation with operational execution. This layered interaction underscores that the CORPGOV–CIRSCM relationship is not only behaviourally influenced but also contextually bounded by the perceived criticality of sustainability transitions. Based on this backdrop, this study hypothesises that:

H4.Perceived urgency for circularity acts as a boundary condition to eco-innovation leadership.

3 Methods of Research

3.1 Study Design and Sample

This study empirically evaluates its conceptual model utilising firm-level data from Ghana's manufacturing sector, exemplifying a developing economy in sub-Saharan Africa, where circularity transitions are emerging amidst institutional fragility and infrastructural constraints. A structured questionnaire using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) was used to capture respondents' perceptions across four focal constructs: corporate governance, eco-innovation leadership (EIL), circular supply chain management (CIRSCM), and perceived urgency for circularity (PURGENCY). Given the strategic importance of manufacturing in Ghana's industrialisation agenda, this study concentrated on five high-impact subsectors: food and beverages, wood processing, plastics, textiles, and apparel. A theoretically guided purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure access to knowledgeable informants embedded in the sustainability and supply chain decision-making processes. Consequently, the respondent pool was restricted to top- and middle-level executives (e.g., CEOs, managing directors, operations and supply chain managers, and sustainability officers) with a minimum of 3 years of industry experience. This expert-informant design enhances internal validity by minimising bias from peripheral organizational actors with limited strategic oversight.

Based on Adomako and Nguyen's (2024) estimation, the population of registered manufacturing firms in Ghana was approximately 1000. Following protocols established for research in institutionally complex and data-scarce contexts (e.g., Dankyira et al. 2024), a refined sampling frame was constructed using the Ghana Yellow Pages and validated through direct outreach and sectoral associations. A prescreening audit, guided by Dornyei (2007), excluded firms that were inactive, untraceable, or informally dissolved, which are typical of fragmented business ecosystems in the Global South. This process yielded a functional sampling frame for 535 active firms. Questionnaires were distributed to all participants, generating 415 responses (response rate = 77.6%) within a four-week period. As apparent in Table 1, after rigorous screening for completeness, response quality, and patterned missingness, 34 responses were excluded, resulting in a usable sample of 381 firms, which is well above the minimum sample size required for robust structural equation modelling (SEM) (Jamil et al. 2024). Although non-probabilistic in design, the sampling strategy ensured contextual fit and sectoral relevance, capturing heterogeneity across firms operating in supply chain–intensive industries central to the circular economy discourse. This approach reflects established practices in sustainability and governance research across emerging markets, where firm viability and data integrity often take precedence over statistical randomness (Agbeka et al. 2025; Amankwah et al. 2025). Sectoral breadth, methodological transparency, and expert targeting collectively enhance the analytic generalisability and theoretical applicability of the study's findings, particularly for research on governance-driven circular transitions in resource-constrained economies.

| Variable (N = 381) | Frequency (f) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm size | Micro | 50 | 13.12 |

| Small | 104 | 27.30 | |

| Medium | 214 | 56.17 | |

| Large | 13 | 3.41 | |

| Firm age | Less than 5 years | 78 | 20.47 |

| 5 to 10 years | 147 | 38.58 | |

| 11 to 15 years | 105 | 27.56 | |

| Over 15 years | 51 | 13.39 | |

| Industry | Food and beverages | 115 | 30.18 |

| Wood processing | 67 | 17.59 | |

| Plastics | 112 | 29.40 | |

| Textiles | 43 | 11.29 | |

| Apparel | 44 | 11.55 | |

- Note: Micro: 1 to 5 employees, small: 6–30 employees, medium: 31–100 employees, large: over 100 employees.

- Source: Field study based on Halidu et al. (2025).

3.2 Measures of the Substantive Constructs

In line with previous research (e.g., Awuah-Gyawu et al. 2024; Malhotra 2023), this study employed survey items derived from existing literature to enhance the reliability and validity of the measurement items. Consistent with Halidu et al. (2025), to ensure contextual relevance, the survey was subjected to pilot testing with six experts from academia and industry. Their feedback was used to modify and refine the questionnaire prior to its final deployment. Measures of CORPGOV were sourced from Wen et al. (2023), Kazemian et al. (2022) and Ali (2018). Additionally, eight question items were selected from Farooque et al. (2022) to assess the CIRSCM. All nine items used to evaluate eco-innovation leadership were adapted from Jun et al. (2021) and Zhang et al. (2020). Finally, five items for the PURGENCY were adapted from Nguyen et al. (2024). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. In accordance with Hutcheson and Sofroniou (1999), who recommended a factor loading of 0.7 or higher, this study excluded items CORP1, CORP2, CORP7, and EIL1, which had factor loadings of 0.599, 0.543, 0.575, and 0.591, respectively, using the maximum likelihood extraction method. These items were not included in the subsequent analyses.

The exclusion of four items from the CORPGOV and EIL constructs, retaining only those with factor loadings ≥ 0.7, was the outcome of a meticulous empirical refinement process aimed at ensuring theoretical precision and psychometric robustness. These items were not excluded due to poor conceptual alignment but rather due to statistical inefficiency (low loadings and cross-loading) tendencies, which could compromise the unidimensionality and internal consistency of the construct (Yau and Lee 2024; Dall Pizzol et al. 2017).

3.3 Analytical Strategy

The analysis utilised a multistage methodology to ensure both statistical rigour and theoretical coherence (Halidu et al., 2025). Initially, descriptive statistics were computed using SPSS 25.0. The skewness and kurtosis of the data indicated a normality range of −1.179 to +1.76, suggesting the data's normality. It is emphasised that skewness and kurtosis should not exceed +2.58. Subsequently, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS 24.0 to assess the measurement model. Given that the scale items were adapted from the established literature, the CFA concentrated on validating the measurement structure through evaluations of construct validity (including convergent and discriminant validity), internal consistency reliability, and factor loadings, thereby ensuring psychometric robustness prior to model testing.

To examine the conceptual model illustrated in Figure 1, this study utilised a hybrid modelling approach. Hierarchical regression was employed to evaluate direct effects across the baseline and fully controlled models, with Model 1 excluding control variables and Model 2 incorporating them. Mediation and moderation hypotheses were tested using Hayes' PROCESS macro (Models 1, 3 and 4), which facilitates conditional process model estimation of indirect and interaction effects. All continuous predictors were mean-centred to minimise multicollinearity and enhance the interpretability of interaction terms following standardised procedures (Hayes 2015, 2012). Concurrently, structural equation modelling (SEM) was adopted to investigate the full structural model. SEM was chosen for its ability to estimate complex, multi-path relationships between latent variables while accounting for measurement errors, thereby providing a unified, theory-driven perspective to simultaneously test both direct and indirect pathways. This integrative approach ensures alignment between statistical modelling and the study's multidimensional theoretical framework. To further guard against multicollinearity, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) diagnostics were conducted. Multicollinearity was not an issue among the independent variables (CORPGOV: tolerance = 0.896, VIF = 1.012; EIL: tolerance = 0.945, VIF = 1.058; PURGENCY: tolerance = 0.956, VIF = 1.046; FSLACK: tolerance = 0.889, VIF = 1.125).

Represent direct relationship.

Represent direct relationship.  Represent control path.

Represent control path.3.4 Measures of the Substantive Constructs

Table 2 shows the reliability and validity results of the substantive variables.

| Code | Construct/measures (composite reliability/cronbach's alpha/average variance) | Factor loadings | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate governance. For the past 3 years… (0.918/0.928/0.855) | |||

| CORPGOV1 | Our board of directors meet periodically per annum | 0.599 | — |

| CORPGOV2 | The board of directors set clear strategic goals | 0.543 | — |

| CORPGOV3 | My firm's operations are annually audited by an independent auditor | 0.766 | FIXED |

| CORPGOV4 | My firm prepares and disseminates its operational standards to relevant stakeholders | 0.927 | 21.645 |

| CORPGOV5 | Management of my firm ensures annual accountability of the use of resources | 0.772 | 16.587 |

| CORPGOV6 | The board of directors is composed of individuals from diverse backgrounds | 0.953 | 22.319 |

| CORPGOV7 | The board of directors ensure that stakeholders' interests are safeguarded | 0.575 | — |

| Perceived urgency for circularity. For the past 3 years… (0.958/0.960/0.905) | |||

| PURGE1 | Our organisation possesses the cognition of stakeholder expectations regarding its sustainability practices | 0.927 | 31.830 |

| PURGE2 | Our organisation demonstrates considerable need to integrate circularity principles into its operational framework | 0.910 | FIXED |

| PURGE3 | My firm challenges traditional supply chain operations by incorporating circularity | 0.894 | 28.721 |

| PURGE4 | My firm knows that circular supply chain management is critical to success | 0.898 | 29.415 |

| PURGE5 | My firm has observed that its competitors have begun to incorporate circularity into their supply chains | 0.898 | 29.120 |

| Eco-innovation leadership. For the past 3 years (0.985/0.988/0.944) | |||

| EIL1 | Our company shows commitment to assess its product designs to ensure that they are readily disassembled, re-purposed, and recycled | 0.591 | — |

| EIL2 | Our company places strong emphasis on prioritising energy-efficient materials | 0.908 | 38.721 |

| EIL3 | My company is eager to use raw materials that do not pollute the environment | 0.933 | 48.721 |

| EIL4 | My firm embraces a manufacturing process that effectively reduces the emissions of hazardous substances or waste | 0.954 | 53.131 |

| EIL5 | My organisation is committed to ensuring that raw materials are utilised judiciously in product development | 0.930 | 45.850 |

| EIL6 | My firm allocates resources for environmental innovations | 0.964 | 61.197 |

| EIL7 | My firm has incorporated sustainability innovations into its corporate strategy | 0.932 | 47.194 |

| EIL8 | My organisation actively promotes creative thinking among its employees | 0.964 | 58.778 |

| EIL9 | My organisation has aligned its operations with the sustainability requirements of both suppliers and customers | 0.967 | FIXED |

| Circular supply chain management. For the past 3 years (0.914/0.924/0.797) | |||

| CIRC1 | Our products are designed to enable recontextualisation, restoration, and reprocessing | 0.945 | 20.492 |

| CIRC2 | My firm requires major suppliers to use materials that have been repaired, refurbished, or recycled | 0.716 | 15.414 |

| CIRC3 | My firm requires our primary suppliers to employ eco-friendly packaging materials | 0.799 | 17.123 |

| CIRC4 | When procuring products, our company considers the potential for water and energy conservation during usage | 0.794 | 17.127 |

| CIRC5 | Through the distribution network, our company retrieves products approaching the end of their life cycle from consumers | 0.790 | 17.043 |

| CIRC6 | Our firm collects expired or unsold products from distribution networks | 0.738 | FIXED |

| Financial slack. For the past 3 years, my firm… (0.932/0.946/0.879) | |||

| FSLACK1 | Has maintained a stable financial standing | 0.877 | FIXED |

| FSLACK2 | Has experienced minimal difficulty in securing monetary resources to sustain our market-related endeavours. | 0.874 | 26.248 |

| FSLACK3 | Has maintained ample surplus funds | 0.914 | 29.311 |

| FSLACK4 | Is able to obtain the required funds when necessary | 0.849 | 24.593 |

- Source: Field study based on Halidu et al. (2025).

Corporate governance is conceptualised as a framework encompassing processes and structures designed to control and direct organisations. It comprises a set of regulations that govern the interrelationships between management, shareholders, and stakeholders (Abdullah and Valentine 2009). Contextual, resource availability, and environmental factors influence the adoption and performance of corporate governance (CORPGOV). Wen et al. (2023) found that the adoption and performance outcomes of effective CORPGOV practices, such as the composition of the board of directors, audit systems, financial disclosure, and ownership characteristics, are influenced by strategic orientation. They suggest that firms with a global orientation frequently implement internationally recognised governance practices, drawing insights from successful models across various markets. This approach can foster enhanced levels of transparency, accountability, and ethical conduct within an organisation. While further research is needed to explore how effective CORPGOV practices drive firm performance, particularly the mechanism through which CORPGOV practices impact circular supply chains in an era characterised by globalisation, environmental consciousness, and supply chain disruption.

Circular supply chain management constitutes a transformative operational paradigm that incorporates circular economic principles into the core of supply chain strategy and execution. In contrast to the traditional linear “take-make-dispose” model, the CIRSCM adopts restorative and regenerative system designs aimed at extending product lifecycles, reducing material throughput, and enhancing resource circularity (Figge et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2021). In response to escalating ecological crises and the intensifying urgency of climate change, Saroha et al. (2018) assert that CIRSCM emerges not merely as an alternative but as an imperative, facilitating systemic reconfiguration whereby materials are perpetually cycled and exhausted only through complete value extraction within supply networks. Firms with a strong environmental orientation are particularly well positioned to lead this transition. Agyabeng-Mensah et al. (2022) contend that such organisations tend to cultivate dynamic capabilities and engage in innovation trajectories that reinforce circularity across supply chain nodes. Fundamentally grounded in the ethos of the circular economy, the architecture of CIRSCM aligns seamlessly with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in its promotion of responsible consumption and production patterns. Furthermore, the integration of advanced digital technologies, such as blockchain, the Internet of Things (IoT), and predictive data analytics, is poised to act as a catalyst, operationalising circular principles at scale and enhancing transparency, traceability, and real-time responsiveness in closed-loop supply chains (Azmi et al. 2024).

Eco-innovation leadership embodies a leader's strategic foresight and proactive approach to integrating sustainability into the fundamental framework of organizational value creation. It signifies not only willingness but also readiness to reconceptualise products, processes, and business models from the perspective of circularity, prolonging the functional lifespan of resources while systematically reducing environmental externalities (Zhao et al. 2024; Pichlak and Szromek 2021). Such leadership extends beyond mere compliance or incremental environmental improvements; it represents a transformative force that mobilises organizational ecosystems towards regenerative design principles.

When leaders genuinely advocate eco-innovation, they do more than initiate green transitions; they establish an ethos of collective ecological awareness and institutional accountability. This leadership approach fosters a psychologically empowered workforce that aligns with the organisation's sustainability goals. Employees become not merely task executors, but also co-creators of environmental value, driven by the sense of contributing to a purpose-driven enterprise with tangible impacts on sustainable development. In this context, the leader functions as both an architect and a catalyst, translating circular economy principles into actionable strategies, while fostering a resilient culture of innovation capable of navigating the complexities of the sustainability transition (Mignonac 2008).

Perceived urgency for circularity represents an accelerating cognitive and strategic imperative, characterised by an acute awareness among stakeholders that the transition towards regenerative and restorative business models is no longer deferrable. This urgency arises from a confluence of intensifying ecological thresholds, systemic resource vulnerabilities, and the increasing inadequacy of incremental sustainability approaches to address global environmental challenges (Mitcheltree 2023). Although the circular economy is gaining prominence as a paradigm capable of reconciling economic activity with planetary boundaries, academic discourse has predominantly focused on its technical deployment, consumer adoption patterns, and sectoral innovations, often neglecting time-sensitive drivers that compel its rapid assimilation. The temporal dimension of circularity: ‘the imperative of immediate action’ remains conspicuously undertheorized. As Khan et al. (2022) demonstrate through their extensive review of circular economy practices, the literature tends to articulate what and how, but remains largely silent on when, particularly regarding the necessity of accelerated adoption in the face of escalating environmental instability. Bocken et al. (2016) identified this gap, calling for a more rigorous exploration of the psychological, organizational, and strategic antecedents that inform urgent decision-making in circular transitions. Nevertheless, the field still lacks a cohesive theoretical framework to conceptualise urgency as a stimulant for mobilising rapid system-wide changes. Addressing this omission is critical, not merely to enrich scholarly understanding, but also to align academic inquiry with existential realities confronting contemporary production and consumption systems.

3.5 Covariants

From the resource-based perspective of a firm (Peteraf and Barney 2003), this study incorporates financial slack, managerial experience, and industry type as covariates, acknowledging their significance in facilitating strategic innovation. Financial slack, defined as uncommitted liquid resources, serves as a strategic reserve that supports risk taking, investment in innovation, and adaptive responses to external shocks (Tran et al. 2018). Managerial experience, quantified by tenure in leadership roles, represents accumulated expertise in orchestrating resources, guiding change, and aligning organizational systems for sustainable transformation (Dong 2016; Esposito et al. 2023; Tran et al. 2024). While large firms often leverage abundant resources, smaller enterprises can mitigate such limitations through enhanced strategic flexibility and expedited implementation of circular initiatives facilitated by flatter structures and agile decision-making (Sen et al. 2023). Both variables were included in the model to control for the potential confounding effects. Financial slack was assessed using four items from Tran et al. (2018) on a seven-point Likert scale. Their inclusion enhances the robustness of the analysis and aligns with the RBV's assertion that resource heterogeneity underpins sustained competitive advantage in dynamic sustainability contexts. Finally, industry type is incorporated as a structural control to reflect its influence on firms' resource configurations and absorptive capacities for circular practices. Sectoral variation, represented by industry dummies (1 = food and beverages, 2 = wood processing, 3 = plastics, 4 = textiles, and 5 = apparel), was examined to explain the differences in their ability to translate corporate governance mechanisms into circular supply chain outcomes.

3.6 Common Method Bias

To address common method bias (CMB), both ex ante and ex post strategies were implemented in accordance with the guidelines established by Podsakoff et al. (2003). The participants were assured of complete anonymity and confidentiality, with the data being utilised solely for academic analysis. No personal or organizational identification information was requested. The measurement items, adapted from previously validated studies, were evaluated by six experts from both academia and industry to ensure contextual relevance, clarity, and precision. Furthermore, the respondents' self-assessed interest, knowledge, and confidence in completing the survey were recorded. On a seven-point Likert scale, the mean rating was 6.0, indicating high response quality, with ratings ranging from 4 to 7 (See Table 2).

The results of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) indicated that the independent variables account for 75.773% of the variance in the dependent variable, as evidenced by eigenvalues exceeding 1.00. Furthermore, Harman's single-factor test revealed that a single factor accounted for only 26.928% of the variance in the dependent variable, which was below the 50% threshold recommended by Podsakoff et al. (2003).

3.7 Validity and Reliability

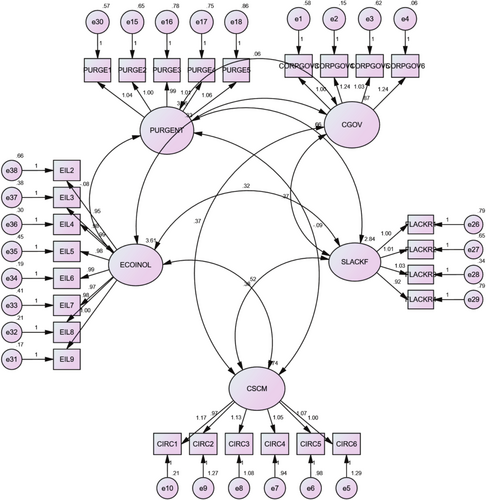

To ensure the high internal consistency of the measurement items, this study assessed the reliability coefficient of the measures following the methodology of Hair et al. (1998). Table 3 indicates that all substantive constructs exhibit satisfactory cronbach's alpha values, ranging from 0.90 to 0.95, which align with the threshold proposed by Eiras et al. (2014). Convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated to confirm that the measurement items uniquely assessed their respective constructs and were distinct from the other constructs (Krabbe 2016). Table 3 demonstrates that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were satisfactory (Hair Jr et al. 2021). In accordance with Fornell and Larcker (1981), this study established discriminant validity among the constructs (see Table 5). Fornell and Larcker (1981, 91) recommend that: “each construct AVE (squared variance within) should be compared to the squared inter-construct correlation (as a measure of shared variance between constructs) of the same construct and all other reflectively measured constructs in the structural model.” They suggested that the shared variance between all model constructs should be less than their AVEs (see Table 4). A comprehensive confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) estimation of the model was conducted using AMOS version 24 statistical tool (Figure 2). The CFA results indicated a satisfactory model fit with RMSEA = 0.058, NFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.965, CFI = 0.969, RFI = 0.940, Chi-square = 721.732, degree of freedom = 314, and p-value < 0.0001. Previous studies emphasise that RMSEA scores of 0.05 reflect a good fit, while values between 0.06–0.08 indicate a reasonable fit. Furthermore, NFI and TLI values exceeding 0.90 are considered indicative of a favourable fit (Gmel et al. 2019; Park 2021; Liu et al. 2021).

| Item | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The questionnaire contains issues we are knowledgeable about | 4 | 7 | 5.70 | 0.986 |

| The questionnaire deals with issues that we are interested in | 4 | 7 | 5.87 | 0.894 |

| We are confident that about our answers to the questions | 4 | 7 | 5.77 | 0.922 |

- Source: Field study (2024).

| Variables | CORPGOV | CIRSCM | EIL | PURGENCY | FSLACK | MExperience | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORPGOV | 0.855 | ||||||

| CIRSCM | 0.304a | 0.797 | |||||

| EIL | 0.175a | 0.223a | 0.944 | ||||

| PURGENCY | 0.005 | −0.054 | −0.020 | 0.905 | |||

| FSLACK | 0.205a | 0.159a | 0.108b | 0.202a | 0.879 | ||

| MExperience | 0.037 | 0.019 | 0.137a | −0.005 | −0.007 | 1 | |

| Industry | 0.020 | 0.099 | 0.046 | −0.031 | −0.092 | 0.038 | 1 |

| Mean | 5.142 | 4.833 | 4.612 | 3.114 | 4.230 | 3.000 | 2.560 |

| Standard deviation | 1.100 | 1.463 | 1.877 | 1.911 | 1.727 | 1.390 | 1.331 |

- Note: The bold represent AVE (Average Variance Extracted) values

- a Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

- b Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

- Source: Field study based on Halidu et al. (2025).

4 Results of Structural Model Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

The structural model of this study was evaluated using covariance-based structural equation modelling (SEM). Ordinary least squares regression was employed to assess the baseline relationship, while Hayes' process macros (Hayes 2017) were utilised to investigate the mediation and interaction effects, specifically using models one, three, and four of Hayes' Process Macros as used to analyse Models 1 and 2 (Table 5). The analysis was conducted in two phases, designated Models 1 and 2. Model 1 did not incorporate control variables, whereas Model 2 explored the influence of the control variables on the model.

| Effect paths | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized coefficient (β)/(Effect) | R-square change (SE) | T-value (LLCI, ULCI)/p-value | Unstandardized coefficient (β)/(Effect) | R-square change (SE) | Value (LLCI, ULCI)/p-value | |

| Direct relationship (H1+) | ||||||

| CORPGOV ➔ CIRSCM | 0.404 | 0.92 (0.065) | 6.213 (0.276, 0.532)/0.0001*** | 0.368 | 0.092 (0.066) | 5.566 (0.238, 0.499)/0.0001*** |

| FSLACK | 0.103 | 0.015 (0.041) | 2.497 (0.022, 0.185)/0.013* | |||

| MExperience | 0.008 | 0.0001 (0.052) | 0.152 (−0.094, 0.109)/0.879 | |||

| Industry type | 0.102 | 0.009 (0.093) | 1.899 (−0.004, 0.207)/0.058 | |||

| Indirect path (H2+) | ||||||

| CORPGOV ➔ EIL ➔ CIRSCM | (0.064) | (0.023) | (0.025, 0.117) | (0.0571) | (0.022) | (0.0201, 0.1066) |

| FSLACK | 0.097 | (0.041) | 2.381 (0.017, 0.178)/0.018* | |||

| MExperience | −0.017 | (0.051) | −0.326 (−0.118, 0.084)/0.745 | |||

| Moderating effect of EIL | 0.102 | (0.032) | 3.145 (0.038, 0.165)/0.0018** | 0.100 | (0.032) | 3.108 (0.037, 0.163)/0.002** |

| EIL at low level | (0.104) | (0.105) | 0.992 (−0.102, 0.310)/0.322 | (0.077) | (0.105) | 0.733 (−0.129,0.283)/0.464 |

| EIL at moderate level | (0.420) | (0.067) | 6.288 (0.289, 0.551)/0.0001*** | (0.388) | (0.068) | 5.711 (0.255, 0.522)/0.0001*** |

| EIL at high level | (0.611) | (0.102) | 6.012 (0.411, 0.810)/0.0001*** | (0.576) | (0.102) | 5.624 (0.375, 0.777)/0.0001*** |

| FSLACK | 0.094 | (0.041) | 2.310 (0.014, 0.173)/0.021* | |||

| MExperience | −0.019 | (0.051) | −0.366 (−0.118, 0.081)/0.714 | |||

| Moderating effect of PURGENCY | 0.032 | 0.010 (0.015) | 2.106 (0.0021, 0.0623)/0.036* | 0.031 | (0.015) | 2.021 (0.0008, 0.0608) |

| PURGENCY at low level | (0.030) | 0.526 | (0.032) | 0.500 | ||

| PURGENCY at moderate level | (0.082) | 0.016* | (0.081) | 0.016* | ||

| PURGENCY at high level | (0.153) | 0.0001*** | (0.149) | 0.0002*** | ||

| FSLACK | 0.085 | (0.042) | 2.043 (0.0032, 0.1677)/0.042* | |||

- Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001.

- Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

- Source: Field study (2025).

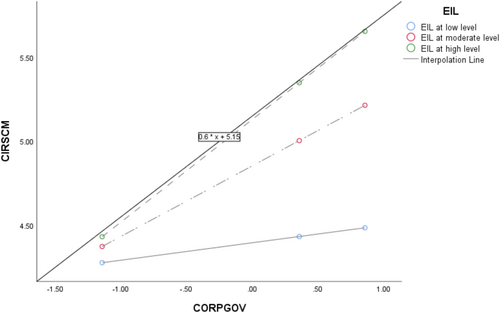

Paolini et al. (2014) emphasise that the slope of a line graph serves as an indicator of the magnitude of a moderator's effect on a given relationship. As shown in Figure 3, the slope of EIL at low levels is less steep than that at high levels, which suggests that the association between CORPGOV-CIRSCM varies at different levels of EIL and that the CORPGOV-CIRSCM link is stronger at high levels of EIL. The results revealed that the effect size of EIL at low, moderate, and high levels was 0.104 (p-value < 0.322), 0.420 (p < 0.0001), and 0.611 (p < 0.0001), respectively.

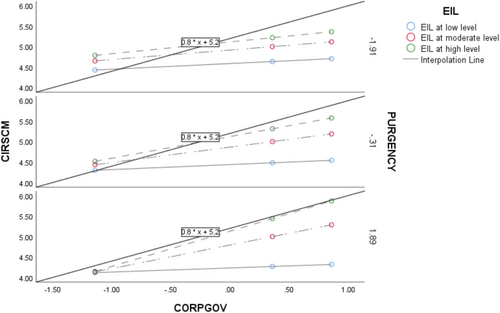

Figure 4 further reveals that higher levels of PURGENCY amplify the moderating effect of EIL in the relationship between CORPGOV and CIRSCM, such that at low levels of PURGENCY, the effect size was 0.030 (p-value < 0.526); at moderate levels of PURGENCY, the effect size was 0.082 (p < 0.016); and at high levels of PURGENCY, the effect size was 0.153 (p-value < 0.0001). The observed variations in slope indicate that under conditions of heightened urgency, eco-innovation leadership serves not merely as a complementary factor but also as a catalytic force, effectively transforming governance mechanisms into tangible circular outcomes. In contrast, in scenarios characterised by low urgency, even robust eco-innovation leadership fails to achieve a significant strategic impact, thereby underscoring the paradox that the effectiveness of leadership in circular transformation is dependent on the perceived importance of environmental urgency.

5 Discussion and Implication of Key Findings

The findings of this study provided five significant insights. Initially, this study proposes a direct and positive link between CORPGOV and CIRSCM (H1). The data revealed p < 0.0001, LLCI = 0.276, and ULCI = 0.532 (Table 5). This result is consistent with Halidu et al. (2025). The justification for this is that CORPGOV acts as an essential framework that defines an organisation's strategic direction and goals, establishes a structure that aligns with sustainability principles, and enforces transparency, reporting, and accountability mechanisms that promote adherence to regulations. This strategic alignment is vital for advancing CIRSCM, which focuses on reducing waste, encouraging resource reuse, and enhancing value creation. This study addresses the academic call to clarify the gap in the understanding of the relationship between CORPGOV and innovation performance (Asensio-López et al. 2019). These results agree with the findings of Al Rawaf and Alfalih (2023), who identified a connection between CORPGOV and sustainability innovation.

Second, this study provides a theoretically grounded contribution by highlighting an indirect pathway through which corporate governance influences circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) through the mediating role of eco-innovation leadership (effect size = 0.064; LLCI = 0.025; ULCI = 0.117). This mediation pathway reveals a more nuanced behavioural process best explained by the SBAT, a novel integrative framework that combines the Stewardship Theory's normative foundations with the intentional, attitudinal, and control-oriented components of the TPB. From this perspective, eco-innovation leadership is not a passive outcome of governance systems but an intentional behavioural expression of stewardship ideals. Governance environments that institutionalise transparency, ethical accountability, and long-term strategic orientation do more than impose sustainability frameworks; they stimulate psychological readiness in leaders to adopt eco-innovative behaviours. This includes fostering positive environmental attitudes, shaping collective expectations, and enhancing perceived capability to act innovatively under uncertainty. Thus, eco-innovation leadership becomes the behavioural conduit through which governance transforms from a set of institutional rules to a catalyst for circularity. The mediation underscores that sustainability transitions are not simply products of system design but of behavioural alignment between institutional intent and leadership agency. For practise, this implies a redefinition of governance from a compliance mechanism to a behavioural enabler. Boards must not only embed stewardship logic into governance frameworks but also engineer leadership contexts that activate eco-innovation as a norm. Embedding sustainability in organizational culture, leadership development, and strategic routines ensures that circular supply chain practices are not merely implemented but are internally driven by behavioural conviction.

Third, this study reveals a key insight: eco-innovation leadership significantly moderates the relationship between corporate governance and circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) with (β) = 0.102, LLCI = 0.038, ULCI = 0.165, p < 0.0018. This shows that the efficacy of governance in advancing circularity depends on leadership aligned with environmental innovation objectives. Through the SBAT, this moderation effect shows that governance systems translate into sustainable outcomes when stewardship values are expressed through leadership practices. Corporate governance provides structural guidance and strategic intent, but without the leadership that enacts these ideals through eco-innovative decisions, such systems risk inertia. Eco-innovation leadership acts as a contextual amplifier, intensifying the influence of governance by aligning leadership behaviours with stewardship expectations. This alignment between governance and leadership behaviour is vital to circularity. When eco-innovation leadership is high, the corporate governance–CIRSCM relationship strengthens as leaders transform governance principles into sustainability-driven actions across the supply chain. Where eco-innovation leadership is weak, even well-structured governance systems may fail to yield circular outcomes due to the misalignment between institutional intent and operational behaviour. This finding signals a shift from viewing governance as a static enabler to recognising the dynamic nature of sustainability leadership. Boards of directors must design governance frameworks and cultivate leadership to embody eco-innovation. SBAT suggests institutionalising stewardship values while fostering leaders who enact those values in innovative ways. For firms seeking circular supply chains, a combination of governance structures and eco-innovation leadership is essential.

Fourth, this study contributes to the discourse on circular supply chain management (CIRSCM) by empirically validating a three-way interaction: Perceived urgency for circularity (PURGENCY) enhances the moderating effect of eco-innovation leadership (EIL) on the relationship between corporate governance (CORPGOV) and CIRSCM (p < 0.036; LLCI = 0.0021, ULCI = 0.0623). Previous studies (e.g., Fredberg and Pregmark 2022) suggest that urgency can both catalyse or constrain innovation; however, the mechanisms through which urgency interacts with leadership cognition and governance structures remain underexplored, a gap this study seeks to address. Grounded in SBAT, the findings indicate that the translation of governance into circular outcomes is contingent upon eco-innovation leadership and the contextual salience of environmental urgency.

PURGENCY functions as a cognitive intensifier, heightening the salience of sustainability and strengthening the alignment between governance and leadership. When perceived urgency is low, psychological triggers for eco-innovation leadership remain inactive, decoupling governance from circular outcomes. This explains why under low PURGENCY, the influence of CORPGOV on CIRSCM is insignificant (p = 0.526). Moderate levels of urgency signal institutional flux, a transitional zone characterised by emerging, yet incomplete, circular policies. In this context, eco-innovation leadership was activated, rendering the CORPGOV–CIRSCM link significant (p < 0.016). At high levels of urgency, when ecological imperatives become unavoidable, the alignment between governance and leadership is fully activated, producing robust effects (p < 0.0001). These findings support the notion that urgency is inherently catalytic. Paradoxically, leadership devoid of urgency lacks effectiveness, whereas urgency without strategic leadership results in disjointed actions. It is only through their combined elevation that circular governance attains systemic effectiveness, demonstrating that neither leadership nor urgency is adequate in isolation. Rather, their convergence is essential for circular transformation. In emerging economies, where economic pressure may dilute sustainability agendas, moderate urgency can foster performative actions (Aragòn-Correa et al. 2020). Only when urgency reaches a tipping point, framing sustainability as morally and strategically non-negotiable, do leaders implement circular strategies aligned with governance. The implication is clear: urgency must align with leadership intent and the governance structure. For the operationalisation of CIRSCM, governance systems must embed stewardship values and foster leadership that is responsive to ecological imperatives. SBAT highlights how institutional design, leadership behaviour, and contextual urgency drive sustainability transformations.

Lastly, in the analysis of the relationship between corporate governance and circular supply chain management, financial slack is identified as a positive and significant control variable (LLCI = 0.022, ULCI = 0.185, p < 0.013), contributing to a modest yet meaningful increase in explanatory power (ΔR2 = 0.015). This finding highlights the strategic importance of financial slack in resource-constrained environments, in which even limited discretionary resources can serve as critical enablers for mitigating risk, absorbing transition costs, and enhancing the governance capacity necessary to support circular innovation. In such contexts, slack may not merely represent excess but rather function as a strategic breathing space essential for circular transformation. Complementing this, while the overall industry-type covariate was statistically insignificant (unstandardised coefficient = 0.102, p-value < 0.058; LLCI = −0.004, ULCI = 0.207), industry-specific dummies revealed differentiated effects on the corporate governance–circular supply chain management (CORPGOV–CIRSCM) nexus. The plastics industry exhibited a significant effect (unstandardised coefficient = 0.409, p-value < 0.009; LLCI = 0.103, ULCI = 0.716), suggesting that corporate governance mechanisms in this sector are more effectively translated into circular supply chain outcomes. Conversely, the wood-processing industry exerted a suppressive influence on this relationship (unstandardised coefficient = −0.496, p-value < 0.008; LLCI = −0.863, ULCI = −0.130), potentially reflecting structural rigidities or weak regulatory alignment with circularity goals. Meanwhile, sectors such as food and beverages, textiles, and apparel demonstrated statistically insignificant moderation effects, indicating heterogeneous sectoral readiness and differing institutional receptivity to governance-led circular transitions. The results show that managerial experience does not significantly affect the model (LLCI = −0.094, ULCI = 0.109, p < 0.879). Although Okrah and Irene (2023) emphasise managerial experience's significant role in enhancing firm performance, this study's findings may indicate a misalignment between tenure-based expertise and sustainability-driven transformation. In many developing economies, managerial experience often comes from legacy systems rooted in linear, cost-driven models, which may constrain the adaptive capacity for circular innovation. Consequently, experience becomes a proxy for path dependency, and not a strategic asset for circularity. This finding challenges the assumptions about experiential capital, suggesting that in transitional economies, quality, not quantity, of experience determines alignment with circular supply chain innovations.

5.1 Theoretical and Managerial Contribution

This study advances the theoretical understanding of CORPGOV-CIRSCM literature by conceptualising eco-innovation leadership (EIL) as both a behavioural conduit and a strategic enabler through which corporate governance is translated into circular supply chain management (CIRSCM). Rather than viewing governance as a static framework of compliance, findings from this study demonstrate that leadership functions as an active mechanism that operationalises governance intent. In practise, robust governance systems are insufficient unless they are complemented by leaders who internalise ecological values and drive innovation with intentionality. Again, to effectively identify and nurture eco-innovation leadership (EIL), organisations must incorporate ecological innovation competencies into their leadership development frameworks and succession-planning strategies. This involves integrating environmental stewardship criteria into executive appraisals and utilising diagnostic tools such as eco-leadership scorecards and sustainability-oriented capability assessments. Talent development programmes should focus on cross-functional circular economy projects, environmental foresight simulations, and experiential learning embedded in real-world sustainability problems. These interventions assist firms in detecting latent leadership capacity and accelerating their eco-innovation readiness. On the policy front, translating perceived urgency into actionable governance changes necessitates formal institutionalisation. Firms can operationalise urgency by embedding sustainability performance metrics directly into board evaluations, introducing environmental risk dashboards that flag early signals of ecological pressure, and tying executive incentives for circularity outcomes. Urgency-to-action protocols, such as mandatory scenario planning or automatic reviews of material flows during environmental disruptions, ensure that governance systems respond adaptively rather than reactively.

Although the effect sizes of EIL's mediation (0.064), moderation at low (0.104), moderate (0.420), and high (0.611), and its urgency-conditioned variation (0.030–0.153) may appear modest, they carry disproportionate practical value. Even marginal improvements in leadership orientation can yield significant gains in translating governance intent into circular outcomes, particularly in resource-constrained economies, where capacity is often limited but responsiveness is high. Sector-specific institutional responses are critical. In industries historically resistant to change, such as wood processing and textiles, regulatory agencies should introduce sector-calibrated incentives, such as green subsidies, material reuse tax breaks, or circular certification schemes, to align private incentives with public sustainability goals. Finally, managerial experience should be evaluated not by tenure alone but by circularity relevance: how closely one's experience aligns with circular economy principles.

5.2 Limitations and Conclusions

While this study presents an integrative behavioural framework for comprehending the interaction of governance, leadership, and contextual urgency in shaping circular supply chain management (CIRSCM), several limitations suggest avenues for further research. First, the data are sourced from an emerging economy context, where institutional logic and cultural interpretations of urgency may differ from those in developed economies. Comparative multi-country studies would enhance generalisability and uncover culturally embedded patterns of stewardship and leadership alignment. Second, although this study advances SBAT, it does not explicitly consider informal power dynamics or resistance to change that may moderate leadership activation. Future research could incorporate political behaviour and psychological safety as additional layers that influence behavioural alignment. Again, future research should employ a mixed method and longitudinal design to enhance causal inference and elucidate deeper behavioural mechanisms. Although this study offers valuable cross-sectional insights, qualitative methods such as interviews or case studies could shed light on leadership enactment and governance translation processes that remain obscured in survey data. Similarly, longitudinal designs are essential for mapping the temporal progression of circular transitions, testing the directionality of governance–leadership–urgency interactions, and capturing how eco-innovation leadership evolves over time in response to changing institutional pressure. In conclusion, this study reconceptualises governance as a behavioural system, not as a static structure, in which circular outcomes emerge only when institutional intent aligns with leadership agency and contextual urgency.

Author Contributions

M.A.-G., A.O.F., O.B.H., B.A.G. and S. A. A. equally contributed in the conception and development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.