Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Digital Era: The Role of Digital Financial Capability and Anti-Money Laundering Compliance

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Although sustainable entrepreneurship (SE) is increasingly recognized as a vital solution to global problems, the influence of financial compliance—specifically, anti-money laundering (AML) laws on SE remains unexplored. This paper investigates the impact of digital financial capability (DFC) on sustainable entrepreneurship in 100 countries between 2012 and 2022, considering the moderating influence of AML compliance. The study incorporates various factors to develop DFC and SE indices. To address potential endogeneity, heteroscedasticity, and autocorrelation in the data, this study uses the two-step system generalized method of moments (GMM) approach, which is assessed using Driscoll–Kraay (D–K) regression, to guarantee robust and trustworthy estimates. The findings revealed that countries within the sample, theoretically align with Dynamic Capability Theory regarding the relationship between DFC and SE. Furthermore, the moderating role of AML compliance has a positive impact on the DFC-SE relationship in advanced countries, increasing it by 20.2%. However, AML laws moderated the adverse effects of DFC on SE in developing countries by 45.8%, driven by variations in regulatory stringency between developed and developing countries. This study closes a significant gap in the literature by incorporating financial compliance into the DFC–SE relationship. These insights help entrepreneurs and financial institutions to optimize costs and promote ethical practices by understanding risk profiles.

1 Introduction

Sustainable entrepreneurship (SE) is gaining popularity due to its critical role in tackling global issues such as poverty alleviation, environmental degradation, and improving quality of life (Belz and Binder 2017). As the global economy shifts from traditional marketplaces to a technology-driven world, entrepreneurs are using digital infrastructure and innovations to generate chances for sustainable growth (Babajide et al. 2023). This trend emphasizes how entrepreneurship is becoming more and more important in accomplishing several UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) including poverty reduction, economic growth, and environmental sustainability, making SE a key global policy concern.

However, for SE to thrive, entrepreneurs must have access to and use financial services efficiently in addition to having creative ideas and digital technologies. The performance of entrepreneurship depends significantly on the accessibility of financial services. Researchers have consistently highlighted the crucial role financial support plays in fostering entrepreneurial ventures (Fang et al. 2024; Moro et al. 2020). Access to funds alone does not guarantee success, effective utilization of financial resources is also essential. A report by CB Insights highlights the fact that 38% of businesses fail due to a lack of financial capability (FC) (CB Insights 2022). This demonstrates the growing significance of digital financial capability (DFC), or the capacity to use digital tools to make wise financial decisions. In this digital era, DFC can enhance the decision-making process because we are unable to identify the difference between digital technologies and daily financial activities (Kang et al. 2024), enabling entrepreneurs to address social and environmental issues.

Despite these progressions, many sustainable ventures require financial backing from banks for long-term sustainability. A report by Forbes indicates that 85% of small businesses struggle to obtain financing from banks. Scholars argue that entrepreneurship and economic growth are affected by inadequate financial systems (Ajide 2023; Doern et al. 2019). Illicit activities, including money laundering (ML), significantly diminish the effectiveness of the financial system. According to Issah et al. (2022), ML gains from illegal activities are primarily channeled into the banking system, which serves as a conduit for them. Mekpor et al. (2018) and Clarke (2021) assert that this process weakens the integrity of the financial system and undermines the stability of financial businesses.

In this context, anti-money laundering (AML) laws are essential to improve inclusive services effectiveness and, in turn, encourage entrepreneurship (Ajide and Ojeyinka 2022). ML increases the costs and inefficiencies associated with entrepreneurial ventures and reduces the competitiveness of the products produced. AML regulations have a big impact on business and entrepreneurship growth, especially in developing countries, where their crucial contributions to fostering a safe and reliable financial environment are highlighted (Clarke 2021). Furthermore, SE, which focuses on social and environmental issues Bonfanti et al. (2024) rely heavily on a robust financial system.

Similarly, it is interesting to note that ML can affect entrepreneurial ventures in several ways. Financial institutions (FIs) may become more vigilant and impose stricter controls in response to ML (Ajide 2023). As FIs grow more careful in their lending policies to avoid risks connected with ML, legitimate entrepreneurial projects may find it increasingly difficult to acquire fair financing. AML regulations can play a role in promoting the country's image and attracting foreign investors. Thus, AML efforts can secure FIs and the business environment (Nicholls 2023). Therefore, there is a notable gap in understanding how DFC affects the sustainability of entrepreneurial endeavors inside the framework of AML laws within the country. In this context, the impact of AML regulations on this relationship remains unclear.

To address this gap, we are taking AML regulations as a moderator in this study as financial compliance. Based on Teece (2007) Dynamic Capability Theory (DCT), the study views DFC as a dynamic capability that empowers entrepreneurs to adjust to financial instability and regulatory changes. The external environment, represented by AML regulations, either facilitates or limits the efficacy of this capability. Using this viewpoint, we investigate how entrepreneurs respond to institutional settings and pursue environmentally and socially sustainable endeavors by utilizing digital financial tools. In keeping with the objectives of the UN Sustainable Development Agenda, including Goal 16 on justice, peace, and strong institutions, we contend that bolstering AML regulations helps create a safe and welcoming business climate. An international threat associated with organized crime is ML, and successful AML policies not only prevent illicit behavior but also advance sustainable development and economic governance (Clarke 2021; Hendriyetty and Grewal 2017). Integrating the AML regulatory approach along with other frameworks such as labor laws, corporate social responsibility, and tax and subsidies can prove advantageous in addressing global policy concerns surrounding SE. Furthermore, the study includes some control factors such as market dynamics (MD), trade openness (TO), and government support and policies.

The present study looks at the link between DFC to promote SE, with a particular emphasis on financial compliance, that is, AML framework as the moderator in 100 countries between 2012 and 2022. The motivation for the study comes from fluctuating economic conditions and instability in the financial system, which pose significant challenges to entrepreneurship like access to finance and regulatory challenges. DFC is essential for entrepreneurs to mitigate and navigate these uncertainties, yet its effectiveness depends on robust financial compliance mechanisms. This dynamic possesses an important query Does AML enforcement help or hurt DFC's ability to encourage SE? The research advances the body of knowledge in the sector and offers practical recommendations for promoting a developed society with enhanced DFC.

The following is how the current study adds to the body of existing literature: (1) this paper is the first to examine the link between DFC and SE, offering valuable insights into how DFC promotes SE. (2) Introducing AML as a moderator provides relevant significance in forming the bond between DFC and SE and mitigates the risks of financial crimes. (3) The study also accounts for key control factors such as dynamics of markets, government support, and TO to assess their influence on SE.

This research contributes to the number of SDGs. It aligns with SDGs 1 (No Poverty) by giving access to financial resources that encourage entrepreneurial activities, 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by empowering entrepreneurs to build sustainable businesses, 10 (Reduced Inequality) by providing digital financial tools to underserved populations, while AML regulations help build trust and promote justice in financial transactions, supporting strong institutions and entrepreneurship, that is, SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions).

The following part of the paper consists of a comprehensive review of the existing literature, hypothesis formulation, and the establishment of a theoretical and conceptual framework concerning specific variables. The next section concerns the methodological approach. Subsequently, results and discussions are provided. The last part is regarding the results–theory alignments, suggested policies, and future directions.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Digital Financial Capability and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

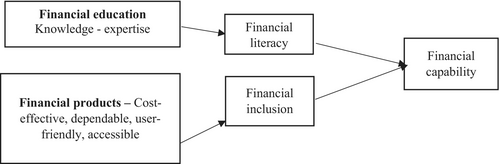

Financial capacity places more focus on behaviors that represent real interactions with the environment than financial literacy (FL) does. It differs from FL because it may present conversion issues from knowing to doing. Scholars have been becoming more and more interested in the concept of FC (Sherraden 2013; Xiao et al. 2015, 2022; Zhang and Fan 2022). Previous studies have clarified the meaning and measurement of FC. FC has been characterized in some research as “Financial capability pertains to the expertise, skills, and behavior required to effectively utilize inclusive financial services and making well-informed and sound business decisions.” Additionally, some studies have argued that FC's fundamental components are the financial environment and conditions. In simpler terms, even if individuals possess the required knowledge and understanding about inclusive financial services and goods, their use of them may be restricted if they are not available to them. Figure 1 shows the FC structure, which shows that FC requires a comprehensive approach that combines FL with accessible and reliable financial products through financial inclusion.

Source: WorldBank.org/financial capability survey around the world and (Sherraden 2010)

.SE incorporates the ideas of sustainable development and entrepreneurial activities (Cohen 2006). It seeks to provide a balanced strategy in which entrepreneurs simultaneously pursue social, economic, and ecological objectives, promoting long-term value creation that is advantageous to the environment, the economy, and society (Huang et al. 2023). Given the importance of FC in influencing the results of sustainable entrepreneurial endeavors, the association between FC and entrepreneurial sustainability has been a matter of policy for nations worldwide. Fewer researchers have concentrated on the FL and startup performance relationship (Calcagno et al. 2020; Li and Qian 2020). Eniola and Entebang (2016) studied that financially literate entrepreneurs possess greater aptitude for gathering and analyzing basic financial data, have greater access to finance for their projects, and are more risk-takers. Several scholars argued that FL is an ethereal resource for people and has a statistically significant positive influence on entrepreneurial performance.

The rising trend of digital technologies in the financial sector has widely recognized the significance of digital financial literacy (DFL). Studies have widely recognized the role of DFL in mitigating the risk of financial crimes. Lyons and Kass-Hanna (2021) investigated that DFL does not function well when people lack awareness of digital financial habits. Although certain elements of FC on the performance of entrepreneurship have been previously viewed by researchers Beck et al. (2015), Wu et al. (2020), and Nasar and Akram (2022), a comprehensive analysis is needed to fully understand their impact. However, its impact on SE or entrepreneurial ventures sustainability has not been thoroughly comprehended. In this particular situation, DFC could play a more significant role in SE as compared to DFL, theoretically.

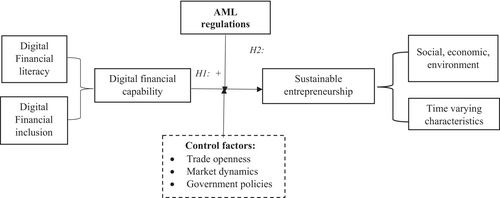

H1.Digital financial capability and sustainable entrepreneurship are positively related.

2.2 AML Regulations as a Moderator and Interacting Term

The increasing use of digital technologies by entrepreneurs and businesses, such as e-wallets, digital credit, and mobile banking, makes it possible for socially inclusive, ecologically responsible, and financially feasible entrepreneurial endeavors (Rapina et al. 2023). The use of digital technologies to enhance entrepreneurial performance is not a standalone process. Several researchers agree that this relationship strongly relies on the institutional context (Amjad et al. 2021). In particular, a strong link between ML and crime funding exists, which undermines financial integrity, good governance, and institutional trust, elements that are necessary to create a favorable atmosphere for entrepreneurship and digital financial innovation (Sajjad et al. 2023). There are currently numerous initiatives underway to create laws, rules, and policies to reduce ML problems in the economy and strengthen the financial system. Thus, the term “anti-money laundering” (AML) refers to programs like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), intelligence sharing, and the establishment of policies aimed at addressing ML-related problems (Ajide and Ojeyinka 2024). AML improves the financial system's and the economy's overall transparency, trust, and confidence (Yıldırım and Rafay 2021). AML rules exert a substantial effect on business operations and entrepreneurial development because of their crucial responsibilities (Ajide 2023).

Many countries are currently putting AML regulation laws into place because ML erodes financial discipline in the economy and distorts transparency. Certain academics have noted that ML harms the aspirations for growth of less developed nations (Bartlett 2002). This group of academics contends that by distorting the financial system, ML lowers economic activity. The financial sector is the main conduit for the majority of ML activities, therefore the negative effects on it trickle down to the real sector and ultimately to the economy as a whole.

Finances are important for entrepreneurship as they help businesses to grow and succeed. When financial systems are well-developed, they efficiently allocate money to the business sector, which can lead to entrepreneurial growth. However, in places where a financial structure is not adequate, it might harm entrepreneurship (Ibrahim and Alagidede 2020). One of the major reasons that weakens the financial system is ML.

On one side, AML builds trust and transparency in the financial system, which can ultimately benefit businesses. However, AML regulations impose compliance costs and burdens on the financial system, which are transferred to the customers, including businesses (Ofoeda 2022). Small or emerging businesses might encounter greater challenges in accessing financial services due to increased compliance costs, and this could harm entrepreneurship and slow down economic development (Ajide 2023).

To resolve inconsistencies in variable connections, authors such as Baron and Kenny (1986) recommend the use of moderating variables. In this context, the growing importance of DFC on SE has garnered increased attention (Luo and Zeng 2020; Wang 2024), however, the degree and direction of this link often differ depending on institutional and regulatory frameworks. AML compliance may have a dual impact on how DFC results in long-term entrepreneurial outcomes. Usman et al. (2025) stress the significance of regulatory frameworks that are both strict and flexible—able to support innovation while addressing the particular risks posed by financial technologies. However, there is still a dearth of empirical research confirming the possible moderating influence of AML regulations on the DFC–SE relationship. To fill this knowledge gap, the current study investigates how AML frameworks interact with DFC to either facilitate or impede the growth of SE, providing fresh perspectives on striking a balance between inclusive innovation and financial compliance.

H2a.AML compliance positively moderates the relationship between digital financial capability and sustainable entrepreneurship.

H2b.Stringent AML compliance negatively moderates the relationship between digital financial capability and sustainable entrepreneurship.

2.3 Navigating Theory and Conceptualization: Establishing Frameworks

The conceptual framework identifies SE as a dependent variable, influenced by DFC which serves as an independent factor. As a moderator, an AML regulatory structure comes next, which potentially strengthen and weaken that relationship. DFC can be examined using a variety of indicators such as DFL and digital financial inclusion. The relationship among the variables as depicted in Figure 2, represents the conceptual framework of the study.

2.4 Theoretical Framework

Institutional theory and DCT are two complementary theoretical stances that are used in this study. According to institutional theory, official and informal regulations, such as governance structures, norms, and regulatory frameworks, influence entrepreneurial activity (North 1990). Institutional environments can either help or hurt entrepreneurial outcomes in situations where financial regulations are well-established. The perceived legitimacy of entrepreneurial endeavors, financial system credibility, and financial access are all impacted by these regulatory frameworks (Sobel 2008). Institutional theory has typically been applied at the microlevel, focusing on individual entrepreneurial goals and conduct impacted by normative and cognitive institutions, and at the meso level, stressing organizational fields, regional norms, and industry structures. Macro-level institutional systems effects have been ignored, notably worldwide or national financial legislation such as AML compliance (See the Graphical Abstract).

To understand how entrepreneurs adjust to various institutional settings, the study uses DCT (Teece 2007). DCT describes how businesses adapt to changing surroundings by developing, integrating, and reconfiguring both internal and external resources. According to this paradigm, DFC is seen as a flexible tool that helps entrepreneurs deal with financial limitations and regulatory uncertainties. An understanding of the factors that promote or impede SE can be gained from the interplay between institutional forces (like AML legislation) and entrepreneurial capabilities (like DFC).

This research is the first to address the conflicting findings around AML regulations and their impact on entrepreneurship, building on the gaps in the literature stated above. Moreover, it contributes theoretically through the macro-level application of institutional theory, a method that has been mostly disregarded in earlier research.

3 Research Design and Methodology

The influence of DFC on SE is examined in this study under the framework of DCT, which highlights how individuals and businesses may innovate and adapt to changing financial conditions. Furthermore, based on Institutional Theory, the study examines the moderating effect of AML laws, acknowledging how formal institutional frameworks affect DFC's ability to promote sustainable entrepreneurial activity. The sample, which comprises the highest number of panel data available, spans 100 countries from 2012 to 2022. Given that, the AML index was introduced this year, so data starts from 2012. The Winsor 2 normalization procedure was used to standardize the data. STATA-15 econometric is used to handle, estimate, and analyze the data process. The sample countries are shown in Table A1.

SE is taken as a dependent variable; proxies GDP per capita measure the economic dimension (Muñoz and Cohen 2018), while the inequality rate and education measure the social dimension (Huang et al. 2023). CO2 emissions are used to quantify the environmental component (Sadiq et al. 2022). Thus, it is essential to combine all three dimensions. To reflect the dynamic nature of SE, as Harvard University asserts that entrepreneurship is best categorized by the dynamic capabilities of business, we use time-varying variables from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitoring database, such as innovation, entrepreneurial intentions, the number of early startups, established businesses, entrepreneurship expectations, female entrepreneurial activities, and the entrepreneurial spirit of decision-making, which have been overlooked in the literature (Huang et al. 2023; Kanayo et al. 2021). Principal component analysis (PCA) is applied for the construction of a SE index.

DFC is one of the determinants as an independent variable which includes two key dimensions: DFL and digital financial inclusion indicators. This comprehensive approach enables us to capture the community's digital financial capacity. Data are gathered from World Bank development indicators and the Global Findex Database. The DFC is constructed using the PCA approach. The usage of interaction terms with the DFC and the moderating variable AML regulations is made. Basel Institute on Governance's Basel AML Index is used to assess AML regulations. Basel AML Index is an impartial evaluation of a nation's potential for ML and the efficacy of its AML laws. The index has a range of 0–10. Higher ratings imply a poor AML regulatory framework, whereas lower values indicate excellent AML regulatory efficacy. TO, MD, and government support are control factors. Table A2 provides a thorough explanation of the variables, measurements, and sources.

3.1 Core Model Technique and Robustness Check

To remove the potential issues of endogeneity, autocorrelation, and over-identification, sys GMM is the most appropriate technique (Arellano and Bond 1991). Since this study included panel data, we used sys GMM. To account for potential measurement mistakes or omitted variable bias, GMM permits the use of instrumental variables (Li et al. 2021). Comparing the two-step system GMM methodology to other data panel methodologies reveals certain benefits (Roodman 2009). It allows for a more efficient analysis of a panel dataset and uses moment conditions to ensure that at the true parameter values, their expected value is zero. Additionally, in our study scenario, two Sys GMM is thought to be a superior estimation technique because (N > T) like in our panel data structure number of countries, N (100), time period, T (11).

4 Results and Analysis

4.1 Baseline Results

Significant cross-sectional dependency (CSD) test data show compelling evidence in both models against the null hypothesis in Table 1. Table 1 also indicates the slope heterogeneity occurrence with data estimations. The high value of delta. adj rejects the null hypothesis of homogenous slope. The presence of the CSD and slope heterogeneity compel the study to use advanced stationarity tests to tackle with these econometric problems.

| Test | Fixed effect | Random effect |

|---|---|---|

| Pesaran's test of cross-sectional independence | 44.377, Pr = 0.0000 | 44.811, Pr = 0.0000 |

| Testing for slope heterogeneity | H0: slope coefficients are homogenous |

|---|---|

| Delta | p |

| 18.809 | 0.000 |

| adj. 21.722 | 0.000. |

Cross-section data are added to the unit root test in the CIPS test to address CSD. With linked series (other panel elements), they take into consideration correlation or dependence between observations. This increases accuracy when using CSD to test unit roots in panel data. Using second-generation tests—CIPS tests, as recommended by CSD—the panel unit root was used to verify the data stationarity. Overall, the alternative hypothesis is supported by the CIPS tests, which validate the stationarity of factor variables. Therefore, it is acceptable to use the model incorporating dynamic elements, that is, sys GMM. The entire results of the Pesaran CIPS test are shown in Table 2. CIPS results show that all the variables are stationary at level except AML × DFC and government support, which are stationary at first difference.

| Variables | At level | First difference | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| SE | −2.663** | — | I (0) |

| DFC | 1.642*** | — | I (0) |

| Trade openness | −2.558*** | — | I (0) |

| Market dynamics | −2.731*** | — | I (0) |

| AML | −3.718*** | — | I (0) |

| AML × DFC | −2.095 | −3.410*** | I (1) |

| Govt. support | −2.407 | −3.566*** | I (1) |

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05.

To have a deeper comprehension of the fauna and trend of variables used in the study from the year 2012 to 2022, we used summary statistics. The results of summary statistics in Table 3 show mean, SD, max, and min values. This shows the central tendency measures and data variability of the entire sample. Total number of the observations is 1100. The low mean for SE suggests that there may be challenges in fostering a conducive environment for SE. The mean value of AML compliance indicates a moderate level of compliance across the sample, shows there is still room for improvement.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 1100 | 0.25 | 1 | −2.84 | 1.644 |

| DFC | 1100 | 0.12 | 1 | −1.4 | 2.226 |

| TO | 1100 | 2.844 | 0.976 | 0.154 | 4.68 |

| MD | 1100 | 23.08 | 20.707 | −8.57 | 73.98 |

| AML | 1100 | 5.117 | 0.979 | 2.73 | 6.79 |

| AML × DFC | 1100 | 0.134 | 5.142 | −9.306 | 14.93 |

| GS | 1100 | 23.08 | 20.707 | −8.57 | 73.98 |

- Abbreviations: AML, anti-money laundering; DFC, digital financial capability; GS, government support and policies; MD, market dynamics; SE, sustainable entrepreneurship; TO, trade openness.

Table 4 shows the correlation matrix of the full sample, developing and developed countries sample, which presents the relationship among the variables used. When two or more variables are used in the investigation, a correlation analysis is performed. Finding the multicollinearity issue between the variables, which causes skewed regression results, is the main goal of analyzing the correlation result. Findings indicate that the dependent variable SE has a positive significant relationship among all other variables except AML. AML and SE are negatively significant at a 10% significant level in the full sample. The findings also show a noteworthy positive relation among SE, DFC, AML, the moderation term of AML and DFC, and government support at 5% and 10% significance levels, respectively. Conversely, a negative significant relationship is observed between SE and TO as well as MD at a 10% significance level in the developing countries sample. SE is positively significant with DFC and MD at 5% significance level. Whereas, SE is inversely significant with TO at 10%. However, moderator variable AML and its combined effect with DFC, are positively significant with SE in advanced countries sample results at a 10% level of significance. Ideally, the correlation should be less than 70%. Table 4 shows no multicollinearity issues.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) SE | 1.000 | ||||||

| (2) DFC | 0.285* | 1.000 | |||||

| (3) TO | 0.342* | 0.126* | 1.000 | ||||

| (4) MD | 0.202* | 0.100* | 0.785* | 1.000 | |||

| (5) AML | −0.650* | −0.349* | −0.226* | −0.175* | 1.000 | ||

| (6) AML × DFC | 0.461* | 0.176* | 0.167* | 0.107* | −0.389* | 1.000 | |

| (7) GS | 0.066* | −0.024 | −0.029 | −0.024 | −0.021 | −0.028 | 1.000 |

| Developing sample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) SE | 1.000 | ||||||

| (2) DFC | 0.062** | 1.000 | |||||

| (3) TO | −0.096* | 0.164* | 1.000 | ||||

| (4) MD | −0.101* | 0.047 | 0.788* | 1.000 | |||

| (5) AML | 0.082** | −0.445* | −0.157* | −0.173* | 1.000 | ||

| (6) AML × DFC | 0.067* | 0.079* | 0.156* | 0.042* | −0.437* | 1.000 | |

| (7) GS | 0.063* | −0.008 | −0.032 | −0.001 | 0.026 | −0.002 | 1.000 |

| Developed sample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) SE | 1.000 | ||||||

| (2) DFC | 0.101** | 1.000 | |||||

| (3) TO | −0.211* | 0.175* | 1.000 | ||||

| (4) MD | 0.090** | −0.101* | −0.211* | 1.000 | |||

| (5) AML | 0.140* | 0.073 | −0.753* | 0.140* | 1.000 | ||

| (6) AML × DFC | 0.724* | −0.169* | −0.171* | 0.714* | 0.108* | 1.000 | |

| (7) GS | −0.057 | 0.128* | −0.129* | −0.057 | 0.085 | −0.097* | 1.000 |

- Abbreviations: AML, anti-money laundering; DFC, digital financial capability; GS, government support and policies; MD, market dynamics; SE, sustainable entrepreneurship; TO, trade openness.

- **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

4.2 Results of Moderating Effect of AML Between DFC and SE Across the Globe

Table 5 shows the diagnostic results of two-step sys GMM, which states that the J statistic is 41, meaning that there are more groups (100) than instruments (41). All other values are within the proposed range. For example, the AR (1) p value is less than 0.05, which shows that there is a presence of first-order autocorrelation in the dataset. Whereas the AR (2) value is more than 0.05, we cannot reject the null hypothesis, which means there is no second-order autocorrelation. The Wald test, which shows model fitness, is also significant. Lastly, the Hansen value is within the range of 0.1–0.3 (Roodman 2009). This is the most effective method for using sys GMM. Table 5 displays the two-step system GMM results for the entire sample. The relationship of SE to its lagged value is significant at a 1% significance level, suggesting that past values of SE have a significant influence on current levels. The findings reveal that DFC significantly contributes to the sustainability of entrepreneurial ventures. Specifically, a 1% rise in DFC contributes to a 27% increase in SE. Whereas, there is a statistically significant negative relationship between TO and SE. At the 10% significance level, both AML regulations and the interaction term of AML and DFC exhibit an inverse relationship with SE. This shows that a 1% increase in AML efforts and AML × DFC corresponds to a 2.13% and 3.14% decline in SE, respectively. Furthermore, findings indicate a positive significant relationship between MD and SE at a significance level of 5%. More specifically, a rise in MD corresponds to a 0.3% increase in SE. Government support and policies are negatively insignificant with SE in the entire sample results. Column II of Table 5 demonstrates robustness results via D–K regression, which are consistent with the main model results. The R2 value indicates that 50.4% variation in SE is explained by the variables used in the study.

| Dep variable SE | Main model sys | Robustness |

|---|---|---|

| GMM | D–K regression | |

| I | II | |

| Lag.SE | 0.889*** | |

| (0.026) | ||

| DFC | 0.270** | 0.077*** |

| (0.113) | (0.022) | |

| TO | −0.039 | −0.216*** |

| (0.027) | (0.059) | |

| MD | 0.003** | 0.077*** |

| (0.001) | (0.022) | |

| AML | −0.021* | −0.403*** |

| (0.011) | (0.044) | |

| AML × DFC | −0.031* | −0.382* |

| (0.019) | (0.211) | |

| Government support | −0.009 | −1.856 |

| (0.005) | (1.138) | |

| Constant | 0.122* | 1.519*** |

| (0.072) | (0.248) | |

| Observations | 1100 | 1100 |

| R 2 | 0.504 | |

| AR1 | −3.04 | |

| AR1p | 0.002 | |

| AR2 | 0.45 | |

| AR2p | 0.649 | |

| Sargan | 0.363 | |

| Collapsed | Yes | |

| Hansen (null H = exogenous) | 35.47 | |

| Difference-in-Hansen tests | 0.298 | |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | |

| Lag | 2 | |

| j-Instruments | 41 | |

| Wald-χ2 | 4398.53 | |

| χ2 (p value) | 0.000 | |

| No. of countries | 100 | 100 |

- Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

4.2.1 Results of Moderating Effect of AML Between DFC and SE in Developing and Developed Countries

Column I of the Table 6 shows the main model results of the developing countries. After applying a range of reference models such as OLS, fixed and random model, we adopted sys GMM as a dynamic model technique in this study. As shown in Table 6, the J statistics is 41 according to the results which shows the instruments appropriateness. With the number of the groups (100) exceeding the number of instruments (41), the system GMM is considered to be the most robust method to justify our findings. Arellano-Bond (AR) test was used to check whether there is occurrence of first-order autocorrelation in the dataset. The results show that there is a presence of the first-order autocorrelation because AR (1) value is −3.09 and its p value is less than 0.05. However, the AR (2) test shows value of −0.05 and its p values is 0.958 which justifies that second-order correlation exists in the dataset and therefore rejected alternate hypothesis and cannot reject null hypothesis, means moment conditions are appropriately established as there is no second-order autocorrelation. The findings indicate that SE and DFC are positively significant at the 1% significance level, with a large coefficient value of 0.91. This suggests that a rise in DFC corresponds to 91.9% increase in SE in developing economies. TO has a positive and substantial relationship with SE with coefficient value of 0.496 and statistically significant at 5%. Specifically, a 1% increase in TO can promote 49.6% SE. MD in developing countries plays a significant negative role in SE, indicating that a rise in MD corresponds to 3.8% decline in SE. Similarly, AML regulations and combined effect of AML and DFC also have a negative significant relationship with SE. More specifically, a rise in AML efforts and combined effect of AML × DFC can decrease SE by 12.5% and 45.8%, respectively in developing economies. While government support does have any impact on SE because it is negatively insignificant.

| Dep variable SE | Core model sys GMM | Robustness D–K regression | Core model sys GMM | Robustness D–K regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) | (II) | (III) | (IV) | |

| Developing (I and II) | Developed (III and IV) | |||

| Lag.SE | 1.378*** | 0.612*** | ||

| (0.066) | (0.057) | |||

| DFC | 0.919*** | 1.114*** | 0.830*** | 1.195*** |

| (0.738) | (0.034) | (0.277) | (0.289) | |

| Trade openness | 0.496** | 0.544* | −0.054** | −0.313*** |

| (0.245) | (0.073) | (0.022) | (0.095) | |

| Market dynamics | −0.038** | −0.125*** | 0.0046*** | 0.080* |

| (0.017) | (0.013) | (0.001) | (0.026) | |

| AML | −0.125*** | −0.242*** | 0.098*** | 0.013** |

| (0.013) | (0.060) | (0.026) | (0.004) | |

| AML × DFC | - 0.458*** | −0.550** | 0.202*** | 0.043** |

| (0.117) | (0.193) | (0.055) | (0.016) | |

| Government support | −0.005** | −0.008* | −0.0262 | −0.0008 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.0204) | (0.027) | |

| Constant | 0.633 | −0.849*** | 0.323** | 0.029 |

| (0.589) | (0.138) | (0.157) | (0.081) | |

| Observations | 704 | 704 | 396 | 396 |

| R 2 | 0.302 | 0.288 | ||

| AR1 | −3.39 | −1.77 | ||

| AR1p | 0.001 | 0.048 | ||

| AR2 | −0.05 | 1.10 | ||

| AR2p | 0.958 | 0.273 | ||

| Sargan | 0.614 | 0.413 | ||

| Collapsed | Yes | Yes | ||

| Hansen (null H = exogenous) | 29.35 | 28.99 | ||

| Difference-in-Hansen tests | 0.249 | 0.290 | ||

| Lag | 2 | 2 | ||

| Year fixed effect |

Yes |

Yes | ||

| j-Instruments | 41 | 33 | ||

| Wald-χ2 | 573.11 | 3566.90 | ||

| χ2 (p value) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| No. of countries | 64 | 64 | 36 | 36 |

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Column III shows the main model outcomes from the developed economies sample. The findings reveal that SE is positively significant with its lagged values with a coefficient of 0.612. This suggests that past values of SE have a significant positive influence on current levels. DFC has a positive significant influence on SE in advanced countries at a 1% significance level. This shows that a rise in DFC corresponds to an 83% increase in SE in developed economies. Similarly, MD and SE are positively significant at a 1% significant level. AML regulations and SE are positively significant in advanced countries. Furthermore, the interaction term of AML and DFC shows a positive influence on SE at a 1% significance level which reveals that the combined efforts of AML and DFC contribute positively to SE. This shows that 1% increase in AML regulations in advanced countries boosts the sustainability of the entrepreneurial ventures by 9.8%. Whereas, government support has no impact on SE because of inverse insignificant relation.

Table 6 shows all diagnostic test results together with the related models. As a result, the validity and correctness of the conclusions are guaranteed by the numerous diagnostic evaluations of estimated models. It also meets the necessary estimating presumptions. With a p value of less than 5%, Arellano-Bond (AR1) shows presence of the first-order autocorrelation in the dataset. In the second-order autocorrelation, AR (2) p value is greater than 5%. This suggests that our study is appropriate for the sys GMM estimate approach, as number of countries is more than time period. The results of the Sargan and Hansen tests are 28.99, with p values of 0.413 and 0.290, respectively. This accepts the null hypothesis and supports instrument reliability since over-identifying restrictions are real. As a result, the model shows that the GMM is valid since the instruments are 33 which is smaller than the number of the groups that are 36. All of the parameters included in this study are appropriate for usage, according to the Wald-Chi test.

Columns II and IV display D–K regression results as a robustness check, which are steady with primary model outcomes, further confirming the validity and reliability of sys GMM. The R2 value indicates that 30.2% and 28.8% variation in SE is explained by the variables used in the developing and advanced countries study, respectively.

4.3 Discussion of Key Findings

The significance of DFC in fostering SE is empirically supported by this study, which also looks at the moderating impact of AML laws. The results, which are based on the DCT, indicate that entrepreneurs who possess greater DFC are better equipped to adjust to changing financial technology and use it to further develop their businesses sustainably. Simultaneously, drawing on Institutional Theory, the results indicate how formal regulatory frameworks, such as AML compliance, constrain the enabling environment for entrepreneurship across different economic contexts. The main model results suggest that the SE coefficient value is optimistic, demonstrating the dynamic nature of SE within this context. Advanced and developing economies' results confirm that DFC has a positive and substantial relation with SE at a 1% level of significance. The findings support the alternative hypothesis (H1) and validate the proposed hypothesis. Results are consistent with (Luo et al. 2021; Sari et al. 2023) who demonstrate that DFC helps in promoting entrepreneurial performance in developing countries like China and Indonesia. This makes it clearer how digital financial instruments support the long-term viability of business endeavors. This positive relationship between DFC and SE is similar to Kenya case of M-Pesa, which empowered the small entrepreneurs to thrive in green sectors (Van Hove and Dubus 2019).

Results show that AML measures along with DFC make a notable contribution to SE in advanced countries, indirectly demonstrating their substantial moderating influence. The results support the hypothesis (H2a), which states that AML efforts serve as a moderator to influence the relationship between DFC and SE. Promoting transparency in digital financial transactions results in lowering financial crimes and inequality, and creating a robust institutional framework for the financial system. AML efforts support ethical business practices and legal compliance, thereby moderating the impact of DFC on SE. These results are supported by Nicholls (2023) who stated that AML measures create a transparent and secure business environment that fosters entrepreneurship. AML measures in the European Union (EU) have demonstrated that increased transparency and financial integrity lead to higher formalization and sustainability of entrepreneurial ventures, aligning with our study's results. However, the moderating role of AML exhibits a negative effect on SE and DFC in developing economies due to the stringent AML measures imposed on their financial system. The results support H2b. The findings are backed by (Ajide and Ojeyinka 2023; Ofoeda 2022) which concluded that strict AML regulations often impose heavy compliance on FIs and businesses in developing economies, primarily due to their less developed financial infrastructures and informal financial systems. This makes financial services more expensive and less accessible. AML laws may put additional strain on the financial sector and business firms. Regulations often mandate businesses to maintain yearly financial statements that raise expenses and personnel burden. This suggests, for instance, that small- and medium-sized businesses would not be able to handle the enormous costs associated with AML, which would have a detrimental effect on businesses (Nance 2018). AML laws in developed nations usually take a risk-based approach, allowing proportionality and flexibility according to the degree of financial risk. Developing nations, on the other hand, frequently choose a rule-based strategy with strict compliance standards due to the limited institutional strength.

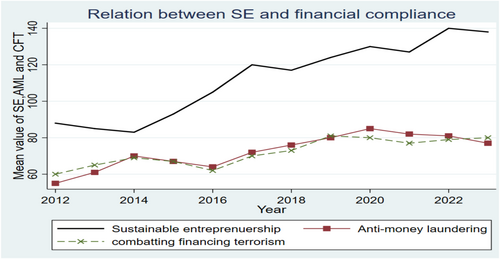

Additionally, other factors such as the dynamics of markets, government support, and TO were used as control determinants in the study. Results indicate that TO has a negative influence on SE overall and in developed countries, backed by Tahir and Burki (2023) who find that average tariffs deter entrepreneurs in BRICS countries. Whereas in developing countries, a positive relationship between TO and SE is supported by Dilanchiev and Sekreter (2015) who found that TO offers entrepreneurs access to a broader spectrum of product markets in Georgia. The dynamics of the market play a crucial role in fostering SE overall and in developed countries. This shows the importance of MD and supports the current hypothesis, which is also in line with the previous study by Kreiterling (2023) which finds that entrepreneurship is strongly correlated with the competitive forces in the market. Government support is negatively insubstantial with SE both overall and in developed countries but negatively significant in developing economies. These findings are consistent with (Friedman 2011; Minniti 2008) who stated that political instability and corruption make government programs and assistance in fostering entrepreneurship useless in developing nations. Figure 3 illustrates the trend between SE and financial compliance, including both AML and terrorism financing measures. There appears to be a positive correlation between the rise in SE and improvements in financial compliance measures (both AML and combating financing terrorism).

5 Conclusion, Recommendations, and Future Research Directions

The current study explores the function of DFC in promoting SE while considering the moderating effect of AML measures on a global scale and across advanced and emerging countries from 2012 to 2022. The entire sample consists of 64 developing and 36 developed countries. Results present that DFC pivotal role in advancing the sustainability of entrepreneurial ventures across diverse economies. These findings emphasize the progressive impact of digital finance in enhancing growth, creativity, and supporting sustainable development in various economies worldwide. The study confirms the statistically significant co-integration among DFC, AML regulations, and SE. However, the analysis finds inconsistent patterns in moderating the relationship between AML regulations and DFC concerning SE, particularly between developed and developing countries. The research underscores the positive role of dynamic market conditions in shaping entrepreneurial opportunities and driving economic progress on a global scale. Furthermore, control factors like TO and government support and policy show variation in their relationship with SE when compared with advanced and developing states. This disparity is attributable to modifications in their respective policies.

The importance of DFC across countries emphasizes how crucial entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities are for navigating intricate digital financial environment. These skills include recognizing opportunities, grabbing resources, and rearranging talents. To mobilize resources, entrepreneurs are urged to form strategic alliances, improve their DFL to adjust to changing market conditions and restructure their business models to take advantage of new opportunities and support environmentally responsible initiatives. The tenets of DCT, which highlight an organization's capacity to integrate, develop, and reorganize internal and external resources in response to quickly changing surroundings, are in line with this. These adaptable capacities also help achieve SDGs 1 (No Poverty) and 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) in the UN's 2030 Global Goals Agenda.

Although AML regulations moderated the beneficial influence of DFC on fostering SE activities in advanced countries governments are encouraged to improve the financial and business environment. Thus, contribute to SDG10 and SDG 16. However strict AML regulations-imposed compliance burdens on businesses and FIs in emerging economies, which create challenges for startups and businesses, potentially hindering their ability to pursue viable sustainable projects. AML compliance involves collecting and analyzing vast amounts of sensitive customer data. Ensuring the privacy and protection of this data while complying with regulations presents a significant challenge for businesses and FIs in developing countries. Data protection laws in these regions are less robust, which contributes to the heightened risk associated with digital financial services and consequently weakens the relationship between DFC and SE.

This research offers a notable contribution by providing a thorough analysis of the complex link between DFC and SE with the moderating role of AML regulations in the context of developed and developing countries. It adds a nuanced understanding by recognizing that AML regulations reduce financial crimes and promote business confidence. Strict AML regulations act as a discouraging factor for SE in developing countries, highlighting the moderating role of AML policies. In addition to providing theoretical insights, this study has practical implications for policymakers, emphasizing the need to lighten AML policies to guide countries toward long-term sustainability in business models and entrepreneurship. The paper makes a practical contribution by highlighting the context-specific impacts of AML in established and developing countries, providing policymakers with insightful advice on how to strike a balance between financial innovation and regulatory compliance. Understanding the institutional factors that influence SE in the digital era is made more conceptually clear by these contributions.

The study's policy implications extend to the policymakers in both advanced and emerging countries. The findings emphasize the need for cost-effective and efficient implementation of AML regulations which entails developing structures and frameworks that promote compliance while reducing unnecessary burdens on FIs. Additionally, it recommends that startups and businesses should incorporate AML regulations into their regular business processes proactively to avoid any excessive liability. This suggests a change to a more comprehensive and integrated method of compliance. Overall, these policy implications show how important it is for policymakers to give priority to the efficient and successful application of AML laws, while simultaneously enticing startups to take the initiative and improve overall compliance efforts. AML regulations allow countries and FIs to take a risk-based approach in developing mitigation measures. Therefore, the compliance costs depend on how well FIs understand their risks and risk appetite. FATF technical support initiatives are one example of an initiative that can help.

The primary constraint of the study is its time span and availability of the data related to DFC, SE, and AML regulations. Although financial compliance offers useful insights, the study addresses only AML. This includes other compliance such as anti-terrorism measures, tax compliance, and consumer protection, where data availability is limited.

Author Contributions

Shama Urooj, Atta Ullah, and Saif Ullah: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft. Haitham Nobanee: conceptualization, validation, visualization, resources, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor and anonymous referees for their comments and feedback. We would like also to thank the editorial assistants and the production team for their support throughout the editorial process from manuscript to publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| # | Country | # | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Algeria | 51 | Korea, Rep. |

| 2 | Angola | 52 | Kuwait |

| 3 | Argentina | 53 | Kyrgyz Republic |

| 4 | Armenia | 54 | Latvia |

| 5 | Australia | 55 | Lesotho |

| 6 | Austria | 56 | Lithuania |

| 7 | Belarus | 57 | Luxembourg |

| 8 | Belgium | 58 | Madagascar |

| 9 | Belize | 59 | Malaysia |

| 10 | Botswana | 60 | Mexico |

| 11 | Brazil | 61 | Morocco |

| 12 | Bulgaria | 62 | Mozambique |

| 13 | Cambodia | 63 | Namibia |

| 14 | Cameroon | 64 | Netherlands |

| 15 | Canada | 65 | New Zealand |

| 16 | Chile | 66 | Niger |

| 17 | China | 67 | Nigeria |

| 18 | Colombia | 68 | North Macedonia |

| 19 | Congo, Rep. | 69 | Norway |

| 20 | Costa Rica | 70 | Oman |

| 21 | Croatia | 71 | Pakistan |

| 22 | Cyprus | 72 | Panama |

| 23 | Denmark | 73 | Philippines |

| 24 | Dominican Republic | 74 | Portugal |

| 25 | Ecuador | 75 | Qatar |

| 26 | Egypt, Arab Rep. | 76 | Romania |

| 27 | El Salvador | 77 | Russian Federation |

| 28 | England | 78 | Saudi Arabia |

| 29 | Estonia | 79 | Senegal |

| 30 | Finland | 80 | Serbia |

| 31 | France | 81 | Singapore |

| 32 | Gabon | 82 | Slovak Republic |

| 33 | Gambia | 83 | Slovenia |

| 34 | Georgia | 84 | South Africa |

| 35 | Germany | 85 | South Sudan |

| 36 | Ghana | 86 | Spain |

| 37 | Greece | 87 | Sudan |

| 38 | Guatemala | 88 | Sweden |

| 39 | Hong Kong | 89 | Switzerland |

| 40 | Hungary | 90 | Syria |

| 41 | Iceland | 91 | Thailand |

| 42 | India | 92 | Togo |

| 43 | Indonesia | 93 | Tunisia |

| 44 | Iran | 94 | Turkey |

| 45 | Ireland | 95 | Uganda |

| 46 | Israel | 96 | Ukraine |

| 47 | Italy | 97 | Uruguay |

| 48 | Jamaica | 98 | USA |

| 49 | Japan | 99 | Vietnam |

| 50 | Jordon | 100 | Zimbabwe |

| Variable | Explanation | Data origin |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainable entrepreneurship | Evaluated using the triple bottom line approach. The economic dimension is represented by GDP per capita, the social dimension by education and inequality rates, and the environmental aspect by CO2 emissions. For dynamic capabilities, the indicators include innovation, decision-making, business establishment, entrepreneurial intentions, infrastructure, expectations, and the number of startups. PCA is applied using these indicators | Global entrepreneurship monitoring (GEM) database and WDI |

| Digital financial capability | Based on financial inclusion and financial literacy. A composite index is created using indicators | |

|

Made and receive mobile payments | Global Findex Database |

|

Payments with credit cards, insurance coverage, mobile account, mobile savings, bank savings | Global Findex Database |

|

Includes the number of ATMs and bank branches available | Global Findex Database |

| Trade openness | Represented by the ratio of exports and imports to GDP | WDI |

| Dynamics of markets | Level of fluctuation in the markets | GEM |

| Government policies | Evaluates the level of government policies supporting entrepreneurship globally | GEM |

| AML as a moderator Basel Institute on Governance's Basel AML Index is used to assess AML regulations | Basel AML index |

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.