An Expert Study of Systemic Influences on Progress Towards Living Wages: A Key to Unlock the Sustainable Development Goals

Funding: This research was funded by a philanthropic gift to the University of Cambridge to support a Prince of Wales Fellowship in Global Sustainability.

ABSTRACT

Ending poverty in all its forms everywhere is Goal 1 of the Sustainable Development Goals the widespread payment of living wages as a minimum could substantially boost progress towards this development goal and others. Living wages, typically set higher than minimum wages, pay enough for workers to meet their needs and those of their families. Without living wages many workers earn poverty wages. Recognising renewed corporate and investor interest in living wages, this paper interrogates the logics and rationalities which shape discussions on living wages, drawing upon 31 semi-structured interviews with living wage professionals. Discourse analysis is used to identify the logics and rationalities which shape organisation-level progress towards living wages. Some logics, surrounding human rights, stakeholder capitalism, sustainable development, redistribution and social justice, encourage the implementation of living wages. Other logics, including shareholder capitalism, profit and mass consumerism, create a chilling effect on the living wages movement. At present, wages are the main mechanism for distributing money, so wage levels impact people's access to services and resources. The living wages agenda is progressing rapidly, comprising a 2024 International Labour Organization meeting of experts, corporate and investor commitments, worker demands, and the growing prevalence of geographically specific living wages calculations. It is therefore crucial that the logics and narratives underpinning decisions on pay are interrogated as these play a pivotal role in progress towards human rights, social justice and the Sustainable Development Goals.

1 Introduction

Progress on poverty reduction has stalled in recent years, and the World Bank estimates that 44% of the world's population are living below the median poverty line of $6.85 per person per day. Furthermore, 8.5% of the world's population lives below the extreme poverty line of $2.15 per person per day (World Bank 2024). According to International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates, 6.9% of the world's population are in working poverty—meaning they earn below the threshold for extreme poverty despite being in employment (ILOSTAT 2023).

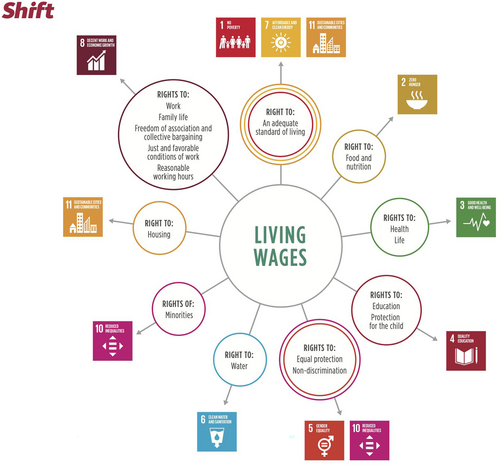

Management scholars have become increasingly interested in the role of the private sector in alleviating poverty through initiatives such as microfinance, serving markets at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’, skills-building and social entrepreneurship (Stefanidis, Casselman, and Horak 2024). However, until recently relatively little emphasis has been placed on the importance of paying living wages, which offer a direct way for the private sector to contribute to the realisation of human rights (Shift 2018, 2021a; Figure 2), lift working people out of poverty and contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (LeBaron 2021; Barford et al. 2022).

Distinct from statutory minimum wages, living wages are voluntarily offered by employers to limit working poverty. While several methodologies can be used to calculate living wages, and living wage levels vary geographically and temporally, the central point is that wages should cover the essential needs of the household, with enough left over for some savings (Global Living Wage Coalition 2022). Note that living incomes are a distinct but related topic, used in the context of households that do not primarily earn their income from formal employment. Living incomes are often referred to in the context of informal work, smallholder farming, self-employment, the gig economy and small business ownership. The rollout of living wages by employers remains embryonic, with just 4% of the top 2000 most influential companies, which together employ 95 million people, paying living wages to their direct employees or having commitments to do so (World Benchmarking Alliance 2024).

Based on interviews with people working to progress living wages across business, finance, non-governmental and international organisations, this study analyses key discourses surrounding living wages, including narratives about what is possible and desirable.

2 Context

The modern concept of living wages is not a new phenomenon, and was addressed in works of Aquinas and Adam Smith (Werner and Lim 2016). In the context of the Second Industrial Revolution, living wages were written about by textile factory owner Mark Oldroyd in Dewsbury, Northern England in the 1890s (Oldroyd 1894). In 1914, Henry Ford pioneered higher pay in the USA with his $5 a day wages, later replicated by others (NPR 2014; History 2021). Five years later, living wages were written into the founding Constitution of the ILO in 1919 (ILO 1919).

The principles of a living wage are also supported by international human rights instruments, which recognise the right of everyone who works to ‘just and favourable remuneration’ (United Nations 1948, article 23.3) and which ‘provides all workers, as a minimum, with a decent living for themselves and their families’ (United Nations 1966, article 7). Living wages are articulated as a human right by The UN Global Compact, a voluntary initiative for the private sector that supports sustainability principles and UN goals (UN Global Compact n.d.), NGOs such as Shift (Shift 2018, 2021a), and living wage campaigns such as Fair Wear (Fair Wear Foundation 2019).

Nevertheless, in-work poverty persists, and globally, just over a fifth of workers live in poverty (ILOSTAT 2019). This is in part because legal minimum wages are generally set too low to meet the income needs of a typical family. In addition, not all employees are covered by legal minima (Sedacca 2022). And lastly, not all countries have minimum wages. Roughly a fifth of all wage earners are paid at or below the minimum wage (Figure 1). Low-pay issues persist for workers in low to high income countries—demonstrating clearly that the political mantra that people can work their way out of poverty is misconceived in contemporary poverty wage labour markets. In this sense, calls for living wages signal a failure of existing pay calculations (Barford et al. 2022).

Since the turn of the millennium, living wages have been revived such that they are now a key avenue for leading corporations to pursue social responsibility, and to contribute to human rights and Sustainable Development Goal targets (Wills and Linneker 2012; Barford et al. 2022). While the most intuitive Sustainable Development Goal home for living wages is Goal 1: no poverty, living wages could play a critical role in enabling several Sustainable Development Goals (Figure 2; Shift 2018, 2021a), because at present poverty is a ‘central barrier’ to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (Leal Filho et al. 2021). Specifically, poverty undermines access essentials, including health care, food, housing, water and education (e.g., McMaughan, Oloruntoba, and Smith 2020; Adeyeye et al. 2023; Desmond 2022; Adams, Stoler, and Adams 2020; Silva-Laya et al. 2020). Further, some groups, including children, women and some minorities are disproportionately poor (e.g., ILO 2017; Albelda 2023; Pew Research Center 2023; Sedacca 2022). Through reducing poverty, living wages can unlock progress towards many other Sustainable Development Goals.

Source: © Shift 2018, p.13).

Although still embryonic, an increasing number of businesses pay their direct employees living wages. This includes > 14,000 living wage employers in the United Kingdom, 368 in New Zealand, and 350 in British Columbia, Canada (in 2022) (Living Wage Foundation 2024; Living Wage Movement Aotearoa New Zealand 2023; Living Wage for Families BC 2022). Living wage movements include City and County Living Wage Ordinances in the United States of America, the Living Wage Movement Aotearoa New Zealand, and the UK's Living Wage Foundation. The COVID-19 pandemic created new impetus for living wages given that many ‘essential’ workers are employed on low wages (Hecker 2020). The global cost of living crisis led an additional 71 million people in developing countries to be classified as poor in the period March–July 2022 (UNDP 2022; Whiting 2022).

Multinational corporations, including Unilever, Tesco and L'Oréal, are beginning to commit to living wages in their global supply chains (Unilever n.d.; Tesco 2021; L'Oréal 2022). The number of influential apparel companies working towards living wages in their supply chains rose from 23% in 2018 to 33% in 2023 (World Benchmarking Alliance 2023). This is a potentially significant development for the estimated 450 million people worldwide who work in global supply chains (UNIDO 2023). In 2016, multinational corporations and their affiliates contributed 36% to global output (Qiang, Liu, and Steenbergen 2021). With such global economic influence, collectively corporations have great potential to reduce poverty, including in countries of the Global South. This is particularly important because, with exceptions such as the Asia Floor Wage Alliance, the living wages movement has gained most traction in the Global North.

The increased engagement of multinationals has been facilitated by an ecosystem of non-governmental and sectoral initiatives to support the adoption of living wages. These include the development of methodologies and benchmarks on living wage levels in different countries and regions (Anker 2006; Global Living Wage Coalition 2018; WageIndicator 2024; Glasmeier and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2024); organisations which support and/or audit multinationals in the process of measuring and closing the gap between existing pay levels and the living wage (IDH 2024; Fair Labor Association 2024; Fair Wage Network 2024); and sector-specific initiatives that seek to improve working conditions in supply chains (ACT n.d.; AIM-Progress 2024; Fair Wear Foundation 2019). In response to the proliferation of living wage definitions and benchmarks, the ILO's February 2024 meeting of experts on ‘wage policies, including living wages’ (ILO 2024) set global principles that living wages methodologies should follow.

Investor-focused initiatives are working to support investors in assessing company performance on living wages and decent work in supply chains, facilitating active investors to engage with companies on these issues (Platform Living Wage Financials 2024; ShareAction 2024; PRI 2024). Furthermore, questions on living wages are being incorporated into sustainability indices such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index and S&P Global's Corporate Sustainability Assessment (Barford et al. 2022). Now, governments are starting to drive greater corporate transparency on living wages: the European sustainability reporting standards require companies to report against ‘adequate wages’ for both direct employees and those in their value chain (European Commission 2023).

3 Literature Review

The scholarly research which informs this paper stems from several different bodies of literature. These include research explicitly focused on living wages, studies of the role of business in society and analyses of the influences of discourse on social and economic change.

3.1 Living Wages

Alongside the rise in business interest in living wages, academic scholarship of living wages is also on the rise. A review of 20 years' of literature on living wages found an increase in scholarly publications after 2014, and a widening of the field from predominantly economics to other disciplines including mainstream management and industrial relations, psychology, health, sociology, social policy and theology (Searle and McWha-Hermann 2020).

The moral case for living wages has been articulated in terms of human rights, social justice and religious ethics (Spectar 2000; Adams 2017; Dobbins and Prowse 2024; Figart 2001; Gardella 2015; Hascall 2014). Drawing on the work of authors John Ryan, Jerold Waltomn and Donald Stabile, Werner and Lim (2016) have articulated living wages in terms of business ethics, based on sustainability (the ability to sustain themselves); capability (workers' ability to develop their capabilities and contribute to society) and externality (the costs to society of low wages, for example, in the need for governments to subsidise wages via the welfare system).

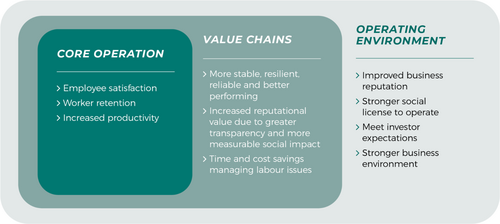

Much of the research (almost half of the articles identified by Searle and McWha-Hermann) focuses on the impacts of living wages, on individuals, organisations and wider society. Some explore the impacts on employment levels, poverty and profit levels (Adams and Neumark 2005), whilst others noted benefits for physical and mental health of workers (Marmot et al. 2010; Burmaster et al. 2015; Bindman 2015), child development (Smith 2015), worker morale and productivity (Carr et al. 2019). Living wages have been linked to a host of benefits for business operations, through more stable workforces, increased value chain resilience and positive multiplier effects in local economies (Barford et al. 2022; Mair, Druckman, and Jackson 2019; Figure 3).

Source: Beales et al. 2022

.A growing body of research seeks to advance the practical implementation of living wages, for example, by establishing new methodologies for calculating living wages (Anker 2006), or benchmarks for living wages in specific locations (Oneh and Samsu 2023). Researchers have also examined the predictors of adoption of living wages by cities (Swarts and Vasi 2011); and in organisations, for example, according to business leaders' orientation towards social justice (Werner and Lim 2017). More recent studies explore the challenges of cascading living wages through global supply chains (Shen, Cao, and Minner 2024; Mair, Druckman, and Jackson 2018). Meanwhile, critical scholars point to the performative nature of some business commitments on living wages, their lack of attention to gender disparities in implementation and the failure of living wages approaches to challenge the status quo of existing business models (LeBaron 2021; Coneybeer and Maguire 2022).

In the context of blossoming, and diversifying, scholarship on living wages (Searle and McWha-Hermann 2020), this paper contributes a qualitative research study of living wages discourses. This approach accesses the reasoning and realpolitiks behind contemporary drives towards living wages, contributing to a research agenda ‘beyond that of mere wage rates, towards a better understanding of the context in which work is done, of its wider impacts and benefits, and of the individual and organizational factors that are required for decent work’ (Searle and McWha-Hermann 2020, 438).

3.2 Business in Society

The living wages movement has re-emerged as the role of business in society has been re-articulated according to stakeholder theory. Rooted in Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Freeman 1984/2010), stakeholder capitalism holds businesses responsible for creating long-term value for shareholders, as well as other stakeholders including employees, customers, suppliers and communities (Porter and Kramer 2019; Business Roundtable 2019). In contrast, shareholder capitalism, building on the work of Milton Friedman, posits that the sole social responsibility of business is to increase its profits (Friedman 1970).

Since the early 2000s, new standards for responsible business conduct have emerged, with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011 (United Nations 2011; Ruggie 2014) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (OECD 2011). In an attempt to prevent and mitigate corporate abuses of human rights, soft law standards for corporate responsibility are being incorporated into legally binding regulation, via new instruments such as the EU's Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (Lafarre 2023; Kuruvilla 2024) and the ongoing development of a binding international Treaty on Business and Human Rights (Joseph and Kyriakakis 2023).

In parallel with the rise of business and human rights, the rise in environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting standards has increased investor scrutiny, with proponents and many scholars demonstrating that corporate performance has a positive impact on the financial performance of investments (Verheyden, Eccles, and Feiner 2016; Eccles and Klimenko 2019; Al Almosh and Khatib 2023; Li et al. 2024). A systematic review of 73 studies found that ESG performance generally has a positive effect on firm value (Li et al. 2024). However, in recent years ESG has come under intense criticism, particularly in the United States of America, where some investors are calling for a return to shareholder primacy (St Clare 2023; Eccles 2022). Others criticise ESG on practical grounds, noting the divergence between different providers' ESG ratings (Berg, Koelbel, and Rigobon 2022), questioning the relationship between ESG rating and improved financial performance (Gibson Brandon, Krueger, and Schmidt 2021), and noting significant variation exists in the adoption and implementation of reporting between and within countries (Paridhi and Arora 2023).

A third development has been the positioning of the private sector as a ‘force for good’ (Ellis 2001; Laszlo, Cooperrider, and Fry 2024) and a key partner to governments in ensuring sustainable development through its ability to drive innovation, productivity, economic growth and job creation (United Nations 2015, para 67). This can occur through investment in local economies (López-Duarte and Vidal-Suárez 2021) and via institutional changes that arise from multistakeholder initiatives or subsidiary social entrepreneurship (Forcadell and Aracil 2019).

Whilst some positive impacts may arise incidental to business intentions, some businesses are going further and embracing the concept of social or sustainable purpose (Cerulli 2020), in part in recognition of the failure of regulation to correct market failures (Mayer 2021). In practice, initiatives such as the B-Corp movement, the World Economic Forum, and the World Business Council on Sustainable Development's Business Commission to Tackle Inequality underline the acceptance of a social role for business beyond simple profit accumulation.

In contrast to the positive narratives of responsible business and sustainable development, critical scholars conceptualise global capitalism as a form of neocolonialism, whose global value chains systematically extract value from countries in the periphery (generally, the Global South) to benefit the core economies of the Global North, whilst upholding unequal hierarchies of race and gender (Quijano 2000; de Sousa Santos 2001; Lodigiani 2020; Stevano 2023). It is also argued that the discourse of responsibility and ethical approach to business ultimately legitimises and consolidates corporate power; power which historically, and legally, prioritises profit over social responsibilities (Banerjee 2008, 2018). Such critiques emphasise how contemporary business models are shaped by the past. LeBaron et al. (2021) links the colonial history of tea and cocoa production to forced labour and poverty wages in today's global supply chains.

Recent systemic crises emphasise the ongoing need to improve the relationship between business and society (Rodrich-Portugal et al. 2023). Recognizing the sometimes-positive contribution of the private sector to sustainable development as well as the damaging and extractive tendencies of some private sector activities, we contend that the magnitude of the private sector necessitates its involvement for serious progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals to occur. Thus, it is imperative that researchers develop detailed understandings of how the private sector is progressing living wages, which remain an underexplored avenue to broaden private sector contributions to development.

3.3 Discourse and Living Wages

Discourses are tangible and powerful, embedded in laws, built into infrastructure and organisational culture, and underpin remuneration (Foucault 1977; Lemke 2011). Discourses simultaneously describe, shape and constitute our social worlds (Foucault 1972; Bourdieu 1993). Highly mobile, the logics, values and modes of organisation of discourses influence the direction of change (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1999). Discourses also navigate competing concerns so can be moulded by the context in which they occur (Urry 1981). Discourse analyses can promote understanding of the pressures and logics, which shape what can be said and done, and how this shapes economies and societies.

There is a dearth of research into the discourses around living wages and their effects, particularly from a business perspective. An exception is Karjanen's (2010) use of discourse analysis, which unpicks differences in the discourses that oppose living wages in the United States of America and the United Kingdom. Market freedom and ‘American’ values were foregrounded in the United States of America, whereas in the United Kingdom opponents claimed the ‘inefficiency’ of living wages as a tool for poverty reduction.

Discourse analysis has been used to explore broader issues of in-work poverty, including precariousness, entrepreneurialism and voluntarism in the creative industries (Samdanis and Lee 2019). Discourse analysis of Ontario's Poverty Reduction Strategy surfaced an assumption that employment will inevitably raise people out of poverty, without discussion of living wages (Benbow et al. 2016). It also revealed that poverty reduction discourses are grounded in narratives such as social inclusion/exclusion rather than in human rights; this occurs alongside a ‘grand-narrative’ that business' contribution is through neoliberal social entrepreneurship rather than the payment of living wages (Smith-Carrier and Lawlor 2017). Research into how international economic inequalities are discursively framed—ranging from outright criticism to celebration of their motivational effects—demonstrates how competing discourses influence whether something is considered desirable or outrageous (Barford 2016, 2017, 2021).

To shed light on the systemic barriers to the adoption of living wages, this article draws upon de Sousa Santos' (2020) approach to structure and agency to characterise influential living wages discourses operating within six spheres that govern social power relations in capitalist societies. The specific characteristics of these distinct but interrelated spheres will vary in different locations based on their history, but encompass: the workplace, market, public sphere, international environment, community and the home. Each sphere has its own form of social agency, institutions, developmental and interactional dynamics, and privileges certain forms of power, law and epistemology. The structures and processes, narratives and norms of these interrelated spheres interact to shape the type, speed and scale of change; nevertheless, Santos is optimistic about the potential for agency to bring about social emancipation. He argues that the identification of these structures assists with identifying the principle form of agency in each sphere and the generation of coalitions for change both within and between spheres. This approach frames our analysis of the competing pressures and systemic features, which shape progress towards living wages.

3.4 Research Question

How do discourses—encompassing structures, processes, and narratives—influence the adoption of living wages by the private sector?

4 Methods

To research living wage discourses, 31 living wages experts were interviewed, including people from corporations, UN bodies, NGOs, investors, and foundations. These interviews were contextualised and analysed in relation to relevant structures, movements and changes. Interviewees were typically senior staff responsible or co-responsible for work packages on living wages (or wages more generally) within their organisation (Table 1). This composition is similar to Springett's (2003) study of sustainable development discourses in New Zealand. Future research would benefit from greater engagement with unions and workers.

| Types of actors on living wages | Purpose in relation to living wages |

|---|---|

| Foundations and NGOs (×6) | Advocating for the payment of living wages; supporting companies, investors, governments, and other relevant actors in adopting living wages and adapting current systems to accommodate for living wage payments. |

| International organisations and specialised agencies (×2) | Promoting international human and labour rights, including the payment of fair wages; helping advance the UN Sustainable Development Goals, including SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth). |

| Companies, mainly multinationals, in sectors including fast moving consumer goods, textiles and clothing, mining (×11) | Employers and supply chain purchasers. Making time-bound living wage commitments; ensuring the payment of living wages in core operation and supply chains. |

| Investors (×6) | Allocating capital towards companies that promote living wages; engaging with or excluding companies that do not have living wage policies; integrating living wages into ESG scoring and proxy voting policies. |

| Investor networks (×3) | Promoting communication, coordination, and collaboration among investors to advance the responsible investment agenda; facilitating learning by sharing best practice and useful tools to integrate living wages into responsible investment practices. |

| Measurement experts (×1) | Designing methodologies to measure living wages; calculating living wages for different regions. |

| Benchmarking initiatives (×1) | Quantifying and publicly reporting companies' progress towards responsible business practices, including the payment of living wages, for the use of investors, consumers, governments, civil society organisations, the media, and multilateral organisations. |

| Workers' unions (×1) | Industrial action; collective bargaining for fair wages and working conditions. |

Interviewees were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling, largely through the research team's networks. Colleagues with strong networks in corporate sustainability brokered some connections, and new connections were sought via email contact and LinkedIn. Though criticised for their ‘network-based convenience’ and selection bias, purposive and snowball sampling suited this study (Parker, Scott, and Geddes 2019). Unconcerned with achieving a representative sample, this study instead aimed to engage professionals at the forefront of advances in living wages. This approach is similar to the Delphi method, which prioritises interviewee expertise and is often used for studies, such as this one, which aim to develop theory in order to inform practice (Brady 2015).

The semi-structured interviews took place between September and November 2021, and were mainly conducted online via Zoom. Online interviewing enabled the rapid completion of geographically disparate interviews, albeit with limited opportunities for wider contextual learning from visiting interviewees' workplaces. Interviews, lasting 45–90 min, were recorded and then transcribed (with informed consent). Interviewees decided whether to share their identity in this paper.

This paper stems from a broader project, which also produced a report on the business case for living wages (Beales et al. 2022; Barford et al. 2022). Accordingly, the interview guide was designed to access professionals' experiences, insights, successes, difficulties, and the business benefits of living wages (Box 1). Some of the interview guide was inspired by earlier research into decent work in circular economy transitions (Barford and Ahmad 2021, 2023, 2024).

BOX 1. Themes in interview guide.

The interview guide included some general themes for all interviewees, as well as some questions, which were tailored to the particular sector such as business, investors or international organisations. Key themes addressed during the interviews include:

Introductory questions: The interviewee's role in their organisation and the organisation's approach to living wages.

Drivers to work on living wages: The motivation to work on living wages and which part of the organisation is leading this work. Evidence and arguments used to promote living wages, and any evidence gaps. Obstacles to living wages which are internal to an organisation. What makes it easier or harder for organisations to progress living wages.

Leadership: The individuals, industries, companies and other actors with leadership roles on living wages. Examples of innovative or ambitious organisations working on living wages. The experience, risks and benefits of spearheading a renewed living wages movement.

Benefits and challenges of living wages: The benefits and challenges of paying living wages, and the costs to businesses of not implementing living wages; paying attention to direct employees and supply chains.

Practical examples: Specific examples of work on living wages, with details of what progress is being made. Review of the process of making living wage commitments, and then implementing and sustaining these.

Operating environment: Coalitions, partnerships, laws, policies, frameworks (such as ESG) and other systemic features that shape support for, interest in, and the need to adopt living wages. The dynamics and negotiation processes for living wage policies and the role of government in promoting living wages. Any changes in interest in living wages over time.

Future outlook: Expected future trends regarding living wages roll out and policies, concerns and the possible impacts on business value and share prices.

In terms of embodied positionality, the research team are white-European, holding post-graduate degrees, all-female and all under the age of 40 at the time of data collection. It was not felt that our identities presented a barrier to recruiting interviewees or building rapport during interviews. Our training in law, economics, geography and social sciences, brought in diverse academic traditions as well as our own insights and myopias. Politically, all three authors support living wages as a wage floor, to the extent that one author was instrumental in her former employer becoming a certified living wage employer. Our own views were not prominent during interviews, yet this analysis was motivated by a shared concern that living wages fulfil their potential.

A Foucauldian approach to discourse analysis meant that as well as analysing oral narratives on living wages (Palmer 2003), we considered structures and infrastructures, and rules and norms. Thus, the context of the interviews was highly important and relevant laws, agendas, and contextual information is key to this analysis. Discourse analysis enabled the questioning of how meaning is connected to power imbalances (Khan and MacEachen 2021). Early analysis identified themes, based on presences and absences and interpretations of meaning (Barford 2016, 2021). To ensure rigour, the team discussed interpretations, challenging one another's ideas as needed. Other trustworthiness checks involved peer review and member checking this paper with several interviewees (Brady 2015; Proefke and Barford 2023).

“We need to get people to think differently and see clearly what the problems are and what to do about it. And I think challenging the discourse is honestly number one on my list, because the rest is… you know, finding the money and all the rest of it follows from people believing that this is the appropriate thing to do.” Head of Responsible Procurement, Multinational Corporation

5 Results

5.1 The Moral Case for Living Wages

“There's an intrinsic motivation you want to have, for your own company, but also your supply chain—you want happy, healthy workers and you don't want human rights violations. So that's a motivation, that intrinsic human rights motivation.” Social Enterprise

“… if people can be in full-time work and not be able to provide the basic human rights, the education for their children, the food, somewhere to live, and so forth—it doesn't sit right that this type of behaviour, not paying the living wage, is being incentivised by the economic activity that we, as a pension community, are financing.” Sustainable Finance Sector

Despite widespread appreciation of the moral case for living wages amongst interviewees, we are far from seeing their adoption with urgency and at scale. The moral impetus for change intersects with existing social, economic and political structures and logics, shaping what is imaginable and possible (Table 2).

| Sphere | Guiding logics |

|---|---|

| Workplace | Shareholder capitalism and efficiency vs. stakeholder capitalism and resilience |

| Market | Competition and mass consumerism |

| Public sphere | Competition for foreign direct investment vs. duty to protect citizens |

| International environment | Human rights and the Sustainable Development Goals |

| Community and home | Diversity equity and Inclusion agenda could be extended to include redistribution as an element of Social Justice |

- Note: Based on: de Sousa Santos (2020).

5.2 The Workplace

“That's the market failure—that it's financially beneficial to pay poverty wages.” Daniel Neale, Benchmarking Initiative

While there are various business benefits to paying living wages (Figure 3), the financial case for living wages is weakly evidenced. No interviewees had a financial analysis of the impact of living wages on their business, yet beyond our respondent pool PayPal's CEO has explicitly connected better financial performance with increasing wages for the lowest paid workers (Zetlin 2021). Several interviewees noted the difficulties in isolating causal links between living wages and financial performance, one of which was the lack of robust data given shareholder expectations of stable or growing profits. Further, the responsibility to maximise short-term shareholder profit was sometimes said to eclipse the moral case and the company's responsibility to its workers.

The need to maintain profit might compromise the implementation of living wages. If companies expect higher wages to be paid by increased worker productivity, the responsibility and costs of living wages are shifted to workers. Interviewees also discussed the risk that living wages result in job losses, as some companies automate processes to keep the total wage bill constant while increasing wages for the remaining workers. Two decades of financialisation have shifted decision-making power, especially within large enterprises. One interviewee explained how money that used to be reinvested to improve production, now tends to be returned to shareholders as short-term profits.

Given these challenges, how can companies progress living wages? One interviewee from an Investor network saw strength in emphasising a company's stated values alongside the longer term payback from improved business performance generated by paying living wages. For her, neither argument works well in isolation, but together they can make a convincing case to business leaders.

“COVID has also brought quite a few investors to think differently about these issues. (…) Having a workforce that's not resilient to shocks has resonated with investors, seeing the impact that it had on the economy at large. So, there is an increased awareness amongst investors that we work with.” Investor network

Stakeholder capitalism and ESG reporting presents a discursive opportunity to make the case for living wages in business terms. In 2021, a compulsory living wage criterion was introduced into S&P Global's Corporate Sustainability Assessment (CSA) for 11 industries with high numbers of low-income workers at high risk of labour issues (S&P Global 2021). According to some interviewees, this development led to companies prioritising living wages. More recently, the backlash against ESG and stakeholder capitalism in some countries may undermine this opportunity (Segal 2023; The Economist 2023) by creating additional barriers to living wages. Faced with inflation and a cost of living crisis, the arguments on both sides became more emphatic: questioning whether businesses can afford to bear the cost of living wages, or asserting that businesses have a responsibility to prevent the lowest-paid workers from experiencing greater poverty. Thus living wages are at the crux of debates about the role of business in society.

5.3 The Market

The market is one of the key spheres in which prevailing discourses constrain companies' ability to implement living wages. Markets, often based on principles of mass consumption, create pervasive pressure to push down wages to keep prices low. Mass consumption of commodities is a driving force for the market, to the extent that ‘commodities tend thereby to negate the consumers who, as workers, are also their creators’ (de Sousa Santos 2020, 453). One interviewee described how this discourse pitches poor consumers against poor workers; the logic is that low cost options are essential so poverty wages are implicitly justified, to the extent that living wages are seen as being bad for poor people. This logic misses the opportunity to confront the causes of poverty, and overlooks people's dual roles as consumers and workers by positioning them in false opposition to one another.

Notably, several interviewees saw living wages as posing a paradigmatic challenge for contemporary business models that rely on low wages. Many global value chains exist because lead firms outsource production to regions with high productivity and low wages. In lower-income countries in particular, wages are suppressed for cost-competitiveness. In the most labour-intensive segments of global supply chains, low wages are sometimes seen as the source of a comparative advantage for both companies and countries. Some businesses are mapping living wage gaps in their supply chains, yet insufficient data availability means that impact on business models and product costs remains unknown. An exception is Fairphone's calculation that paying a living wage premium to factory workers adds $1.50 or 0.33% to the cost of a phone (Fairphone 2020); this minimal markup contradicts the narrative of living wages being financially unsustainable.

Interviewees acknowledged the difficulties of ensuring living wages were paid to suppliers' employees, many of whom are in lower income countries. Lack of transparency in long and complex value chains, and the need for coordinated action within industries particularly where suppliers are serving more than one multinational client, were key challenges. Nonetheless, interviewees also considered that living wages could boost supplier performance, value chain resilience and social impact.

“It really is a buyer's market. It's not a manufacturer's market. Let's face it … So we have to press them on the poor, we have to press them on pricing, wage levels and we're doing that more and more.” Investor

Many unions engage in living wages discussions, with the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) using the term ‘minimum living wages’. The ITUC calls for union involvement in formulating living wages, using unions' cost of living calculations. Unions' wage demands already stem from such calculations, paired with collective bargaining to avoid many workers earning just over the minimum wage with minimal progression beyond that (ITUC 2024). In other words, unions are mindful that a living wage alone cannot resolve concerns around pay, but see value in engaging on living wages.

Market sphere living wages discourses are characterised by constraints on agency—with companies and states presented as having limited power to act. This is a key area to generate evidence and alternative ways of doing things to empower actors in this sphere.

5.4 Governmental Logics

States are the primary subjects of international law and have a duty to take steps to progressively realise economic, social and cultural rights (United Nations 1966, Article 2), including the right to fair wages and a decent living. However, living wages are more often construed as a voluntary commitment of companies rather than as a duty of States, with the ILO historically preferring an approach of ‘minimum wage fixing’ taking into account the needs of workers alongside other factors such as economic development, productivity and maintaining a high level of employment (Raynaud 2017). Most, 90%, of ILO Member States have established minimum wages (ILO 2020), which fall below living wages. This results in widespread working poverty, which worsens when minimum wages lose value amidst rising inflation (ILO 2022b).

“In terms of low wage levels, we see that for many countries this is a competitive advantage, and so being able to develop those industries, for some governments it's been important for them not to push on wages, because they don't want to risk those companies leaving.” NGO

“We're in this space where things like consumer power has been looked at for a long time and has kind of diminishing returns, but we haven't really harnessed citizens' power as an instrument, except for post pandemic when you had wide-scale condemnation and outrage and a lot of good campaigning when brands didn't pay their bills during the pandemic and lots of orders went unpaid for.” Campaigning Organisation

Some states have responded to pressure around living wages in surprising ways. In 2015, then UK Chancellor George Osborne announced a ‘National Living Wage’, but set the hourly rate lower than the independently calculated living wage, and only applied it to people aged over 23 years; UK national minimum wages remain age-related but have since risen and have been criticised for possible consequences in terms of unemployment and the burden on business (Gov.uk 2022, 2024; Race 2024). In countries with strong welfare provision, benefits are expected to make up for shortfalls in pay (Barford and Gray 2022). Thus low-paying employers effectively free-ride on the state, this weakens the imperative for employers to pay living wages. Where social protection is minimal, free-riding takes a greater toll on individuals and households.

Like the market-level discourse, narratives which reinforce lack of agency prevent decisive action on living wages. Companies attribute their inability to act on the lack of State regulation for higher wages; as States shrink from introducing such legislation for fear of alienating the private sector. Nevertheless, there is general agreement that matching minimum wages to living wages, gradually if needed, could scale and regulate living wages. A new approach might emphasise states' legal duty to progressively realise human rights and the corporate responsibility to respect human rights.

5.5 International Logics

Several discourses within the international system support living wages: human rights, decent work, social justice, sustainable development and the need to tackle rising inequality. As noted above, international human rights law and institutions call on states to take steps to progressively realise the right to fair wages and a decent living.1 The ILO calls for a living wage in its Constitution as adopted over a century ago in 1919,2 and most recently in its February 2024 meeting of experts on ‘wage policies, including living wages’ (ILO 2024).

“If companies see something coming, whether it takes 5 years or 10 years to be embedded in regulation, they know that the sooner they start moving, the lower the cost of the transition will be for them.” Adviser, Sustainability social enterprise

Some interviewees saw the greater regulation of living wages as inevitable, comparing it to other human rights-related regulation that was at first seen as a hindrance to business, but is now ‘standard practice’. For example, health and safety, and gender pay equity.

Many interviewees connected living wages with the decent work agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals. While living wages can contribute to at least eight of the Sustainable Development Goals (Living Wage Foundation 2019; Shift 2018), they are nevertheless seen as controversial by some governments and employer associations (Saner and You 2019) and are not an SDG indicator (SDG Tracker 2022). International consensus building on living wages could strengthen recognition of living wages as a key tool for these global agendas.

Criticisms of inequality could also drive momentum on living wages (Wilkinson and Pickett 2010; Piketty 2013). The Business Commission to Tackle Inequality considers inequality as a systemic and urgent risk to business (BCTI 2023), as the richest 10% of people are estimated to own 76% of global wealth, and the poorest 50% hold just 2% (Chancel et al. 2022). The extent of global inequality prompted the formation of the Business Commission to Tackle Inequality (BCTI), a cross-sectoral coalition of organisations launched in 2021 by the World Business Council on Sustainable Development. This coalition characterises inequality as a systemic problem, posing an urgent risk for business and investors. BCTI's flagship report identifies living wages as one of the 10 key actions for businesses to tackle inequality. Some may find a coalition of business leaders calling for redistribution of value surprising, and this nascent discourse is not fully developed in business circles.

Perhaps one of the largest silences in our interviews was history, including colonial history and the more recent pay practices of organisations prior to the implementation of living wages. Low pay is rooted in long-standing value extraction from labour and resources (e.g., ores, raw materials, ingredients), particularly from ‘peripheral countries’ in the Global South to the ‘central’ countries in the Global North. Forward-looking approaches to living wages discourse preclude discussions of responsibility, apology or reparation.

5.6 Community and Household Logics

The racial dimension of living wages was rarely discussed by interviewees, who were predominantly white and based in Europe or the United States. When race was discussed, living wages were seen as contributing to closing ethnicity pay gaps. This is despite the racial dimension to income inequalities (Carr 2023), and globally, most people who earn poverty wages are part of the Global Majority (Campbell-Stephens 2021, uses the term Global Majority). In the United States, 32% of the workforce earns under $15 per hour; however, 47% of Black workers, earned below this threshold, compared with 46% of Hispanic/Latino workers and 26% of white workers (Henderson 2022).

“It's the knife in a gunfight … If I think about our social focus on gender and sexuality, and how we focus on particular topics, it's interesting to me that we don't focus on wages, right? It's too much of a challenge to other norms—and that shows you how much power there is behind staying in the current status quo.” Head of Responsible Procurement, Multinational Corporation

One interviewee highlighted how living wage calculations assume full-time working weeks, so hourly living wages may be insufficient for the many women, and some men, who work part-time often due to unpaid caring roles. Note that in the EU, 31.3% for women and 8.7% of men aged between 15 and 64 work part-time (Lamolla, Folguera-I-Bellmunt, and Fernández-I-Marín 2021). Furthermore, the combination of low-paid work and domestic duties is a double-burden for many women. Another interviewee described the consequences of low pay on young women working in garment factories in Cambodia, Bangladesh and Myanmar. They burn out, not only because of the inadequate working conditions but also because of the extra hours that women have to take on to earn enough to support themselves and their families.

In the context of wages, it is worth noting how economic and identity-based inequalities are often treated separately. Discrimination faced by people due to their ethnicity and/or gender identity has been increasingly recognised and reflected in anti-discrimination laws and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion initiatives. Yet these initiatives frequently focus on the equal recognition of different identities and participation within decision-making, to the exclusion of equitable redistribution of resources (Fraser 2000). Thinking of economic injustice and identity-based discrimination separately overlooks the relationship between them.

6 Discussion

The results presented above help us to answer our research question: How do discourses—encompassing structures, processes, and narratives—influence the adoption of living wages by the private sector? The research process was focused specifically on those at the forefront of living wage discussions: private sector actors or actors engaging closely with the private sector. As such, the findings are from a subgroup with substantial influence over shaping the contemporary living wages agenda. As an international group of interviewees, each will be influenced by the situation within their home countries, as well as international logics that span national borders (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2000; Karjanen 2010; Barford 2016, 2017). As narratives and approaches vary amongst interviews, there is no singular discourse but a set of intertwined logics and arguments, which flex and shift according to ambition and constraints.

The social spheres framework provided by de Sousa Santos (2020) structured the mapping of major influences upon living wages. This is where the interplay between structure and agency occur, as people have some agency to shape structures while also navigating structural constraints. The results above detail multiple influences, of which prominent logics are as follows. In the workplace, a strong emphasis on profits, with wages being seen as a cost, presents a challenge for those promoting living wages. In the market, the drive for low prices can be used to justify low wages. In the public sphere, the fact that legal minimum wages are below living wages means a lack of legal requirement to pay more. Business commitments and international organisations', including NGOs, concerns with the sustainable development goals and human rights support living wages. In the home and community, low pay is gendered and racialised but the connection between economic and identity-based inequalities was often overlooked (Figure 4).

A finer grained approach identifies overlapping and sometimes contradictory arguments, which shape the living wages discourses. Some framings of wages, poverty and the need to pay living wages can be understood as tipping away from, or towards, progress towards living wages (Table 3). For instance, living wages being enshrined in human rights law promotes the need for living wages, meanwhile the SDGs referring to wages but not living wages undermines their importance. Amongst current constellations of intersecting influences are tipping points, arguments, laws and agendas, which push the agenda in a certain direction. Tipping points may also concern the personal engagement of leaders with questions of economic injustice, and to what extent they consider themselves as connected to this (Barford 2017).

| Sphere | Prevailing discourses around living wages |

|---|---|

| Guiding logics | Discursive limits to living wages (−); discursive openings (+) |

| Workplace | Widespread emphasis on the need for profits, with wages typically seen as a cost to employers. |

| Shareholder capitalism and efficiency vs. stakeholder capitalism and resilience |

|

| Market | The logic that consumers want low prices justifies low wages. |

| Competition and mass consumerism |

|

| Public sphere | Many states legislate for minimum wages which are below living wages. |

| Competition for foreign direct investment vs. duty to protect citizens |

|

| International environment | Various governmental and non-governmental international organisations seek to improve pay and conditions for workers. |

| Human rights and the SDGs |

|

| Community and home | There is a racial dimension to income inequalities as globally most people earning poverty wages are non-white. Gendered household norms and expectations impact approaches to living wages. |

| Diversity equity and inclusion agenda could be extended to include redistribution as an element of social justice NIH |

|

- Note: With respect to the ‘workplace’ row, it is worth noting that all three authors produced a report on The Case for Living Wages.

This research contributes to understanding of how living wages are approached and framed, including where attention is directed, and which silences persist. Silences are arguably tricky to identify given their absence, yet they do not go unnoticed. At a 2022 Living Wages Summit one keynote speaker described ‘an overpopulation of elephants in the room’ (Barford 2022). The persistent silences and unresolved contradictions include that living wages are still low wages, and many of the people implementing these would not themselves aspire to earning at this level. There is little discussion about how to resolve the issue of gendered patterns of paid work meaning that even when living wages are paid they may not lift many women out of poverty. This is because wages are calculated at hourly rates and many women's paid work is part-time to preserve time for the unpaid work they also do. Living wages discourses are also future-focused, rarely touching upon historical exploitation or injustices. Similarly, living wages are not often couched in any language about the equitable redistribution of the value created in global value chains. And lastly, there is a risk that living wages are implemented in a ‘top down’ way, rather than through dialogue with workers.

Some of the silences identified above are likely to be tactical, given that living wages done well are an important first step towards addressing working poverty. Experts and professionals working in this field are likely to be acutely aware that focusing on shortcomings and limitations of living wage could sink this budding movement before it has delivered the multi-pronged benefits it offers.

Progress towards living wages can be usefully informed by realistic and timely insight into the systemic barriers and opportunities for living wages. Knowing some of the blockages, barriers or tipping points can help actors to navigate, refute and perhaps redefine points of contention. A notable example in this space is the work undertaken by Shift to change the narrative that wages are a cost to business, by offering a new accountancy model in which living wages are counted as an investment in a business and its staff (Shift 2021, 2023; Barford et al. 2022). Altering the reference points for discourses offers tipping points, albeit always mediated by the wider context.

This study has also shown how systemic constraints pose barriers to how far and how fast companies are moving on living wages. For instance, some companies express strong concerns about living wages making them uncompetitive in relation to rival firms. Others detail the practical difficulties in paying living wages in the value chain, for example as one of many buyers that a factory supplies. In this context, wage policies could boost minimum wages to living wage levels, yet other constraints limit state interventions. What is promising is the potential for systemic change, as living wages discourses are reshaping what is appropriate and possible. Influential members of the business, investor and international community are now putting living wages firmly on the agenda. Over coming years, we are likely to see further working and reworking of wage discourses as narratives shift and institutions recalibrate.

7 Conclusion

This paper addresses the conundrum of why living wages, despite the business benefits and strong moral case, remain embryonic and are experiencing a slow and rather bumpy roll out. Engaging with those at the forefront of the living wages agenda—from across business, finance, NGOs and international organisations—offers insight into what is happening behind the bold statements and headline living wage commitments. This paper identifies the pressures, ambitions and realpolitik surrounding the living wages agenda.

Through identifying dominant discourses relating to living wages, this research shows how competing logics can enable, block and also change the emphasis of the living wages agenda. Influential logics surrounding human rights, stakeholder capitalism, sustainable development, tackling inequality and social justice can encourage the payment of living wages through a strong sense that this is the right thing to do for people's overall well-being as well as market stability and global peace and security. To greater or lesser extents, these approaches seek a more equitable distribution of money between people. Other logics, including shareholder capitalism, the generation of profit, and mass consumerism, create a chilling effect on the living wages movement through their focus on protecting investors and existing business models. These discourses seep between spheres, sectors and countries (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2000), shaping the focus and viability of the living wages agenda.

Given our interest in developing theory to inform practice (after Brady 2015), the new theoretical insights presented here can usefully inform a strategic approach to engaging and appraising the logic, accuracy, myopias and silences of living wage discourses. This can provide a basis for the formation of counter narratives, research for new evidence, or bringing those ‘silent elephants’ into the conversation. While these narratives are carefully calibrated to be palatable to decision makers and navigate competing and sometimes contradictory concerns, they also offer a lever for shifting wider structures.

Given the potential of living wages to unlock progress on a host of Sustainable Development Goals, not least Goal 1: no poverty, future research in this area is greatly needed. Future studies might helpfully extend beyond ‘living wages leaders’ to understand the wider discourses on living wages. Research into the internal organisational dynamics regarding living wages could inform business strategies. Studies of living wages discourses by country (like that of Karjanen 2010), sector, or other aspects could identify possible early adopters, and thus support living wage implementation. Lastly, action research projects involving narrative-led systems change might further explore tipping points for change and document what happens as discourses shift.

Author Contributions

All three authors designed the research project, conducted interviews, and then planned and wrote this research paper. The work presented here reflects the views of the authors, not the views of the organizations they work for.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a philanthropic gift to the University of Cambridge to support a Prince of Wales Fellowship in Global Sustainability. We also thank the following people for their collaboration and guidance within our wider research about living wages: Jane Nelson, Caroline Rees, Anouk Heilen, Matthew Oh, Rachel Cowburn-Waldren, Yvette Torres-Rahman and Zahid Torres-Rahman.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors work on living wages through research and practice. As such they variously collaborate with and undertake work for key actors in this space, including as employees and consultants.