Drugs and biologics in pregnancy and breastfeeding: FDA in the 21st century†

This article is a US Government work and, as such, is in the public domain in the United States of America.

It is a banner year for pregnant women, women breastfeeding babies, and their healthcare providers! Last month, the US FDA proposed major revisions to physician labeling for prescription drugs (including biological products) about the effects of medicines used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Compared to today's labeling, the proposed changes to prescription drug labeling would present more information in a clear and complete way, allowing health care professionals to more effectively counsel and prescribe for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Under development for many years, the proposed regulation represents the evolution and elevation of the science of medicine as it applies to sound prescribing and counseling decisions for unique patient populations.

FOUR DECADES OF PREGNANCY LABELING

FDA regulations on labeling of drugs for use during pregnancy, labor, and delivery, and by nursing mothers were promulgated in 1979 (21 CFR 201) (44 FR 37434 June 26, 1979). Prior to that time, there was no requirement that drug labeling include risk information about in utero exposure. Since then, the regulation has expanded to apply to biological products, but the specific content requirements have not changed. Labeling resulting from this regulation is well known by clinicians as the “pregnancy categories,” referring to the system of five letter designations (A, B, C, D, and X).

In 1997, the FDA began to examine this part of the labeling regulations based on staff reviewers' own experience applying them and in response to concerns raised by professional societies (including the Teratology Society) and other experts. Starting with a public hearing we sought comment on the practical utility and effects of the current models for both pregnancy and lactation, so that we could consider whether updates or modifications of the existing regulations were needed (62 FR 41061, July 31, 1997). We learned a great deal.

Through extensive testimony, it was clear that the pregnancy categories are perceived by health care practitioners (HCPs) as a simple, convenient measure of risk. At the same time, teratologists, genetic counselors, and other experts described how this simplistic system resulted in over-reliance on the letters themselves. Specifically, it was apparent that many HCPs are unaware that the letter category system takes into account a balance of risk and benefit (letters C, D, and X). More troubling was that even among HCPs who are aware, this balanced consideration of drug risk and benefit may not always be factored into clinical practice. For example, assignment to Category A or B often is interpreted as indicating that a drug is “safe for use in pregnancy.” By definition, Category A is assigned when controlled human studies in pregnancy show no developmental abnormalities. Category B is assigned when animal studies show no evidence of embryofetal toxicity or when animal studies show developmental abnormalities in the offspring but studies in pregnant women have not shown that risk. Neither of these definitions can be considered to equate to complete safety. Similarly, Category X is often interpreted as being uniformly dangerous to the fetus. However, some products are labeled as Category X not because of risk, but because their use in pregnancy offers no benefit to the pregnant mother. For example, oral contraceptives were originally designated Category X, because they cannot prevent pregnancy in an already pregnant woman, not because they are human teratogens.

Critics also pointed out that in a categorical system, the degree of risk posed by products within the same category is expected to be similar, which is not the case for FDA's current regulatory framework. The category criteria permit drugs with no known risks and drugs with expected risks to be placed in the same category. For example, Category C is assigned to drugs with demonstrated adverse reproductive effects in animals and to drugs for which no animal testing has been performed. Further, the system does not address potential developmental adverse events on the basis of expected incidence, severity, or reversibility, nor whether there are degrees of risk based on the dose, duration, frequency, route, or gestational timing of exposure to a given product. The dynamic physiology of pregnancy and fetal development are not able to be satisfactorily considered in assigning pregnancy categories.

To Read the Proposed Rule

These concerns are magnified in light of the fact that decisions made by physicians and their pregnant patients about medicine use arise in several very different clinical circumstances. In one type of circumstance, which the 1979 regulations sought to inform, a decision is made about whether or which medication to prescribe for a pregnant patient before embryofetal exposure occurs. Risks and benefits of treatment options can be considered prospectively. Another occurs when a woman who is already using a medicine finds out that she is pregnant. In this situation, risk has already been incurred: what remains are questions about the potential consequences to the developing child. The patient has not had active choice about whether to expose her fetus to the drug's balance of risk and benefit, and thus may perceive the risk and potential consequences quite differently than she would have prospectively. There is a third type of potential circumstance—after a child with birth defects has been born. Most clinicians know well that a child's birth defects may be more likely to be attributed to in utero exposure to a drug if it is Category D or X than if it is Category A or B. If this attribution is erroneous, it can have serious consequences for management of the child's condition and for counseling provided to the woman regarding her future pregnancies or prenatal diagnosis. The nuances and challenges of these and other circumstances faced by clinicians and pregnant women make it essential that they have access in product labeling to up-to-date, clear information about drugs' risks (and benefits) and any uncertainty that remains.

As the scientific base for pharmacologic therapeutics has grown, public expectations for data collection and sharing of information in product labeling has become more sophisticated. FDA recognized this and placed increasing emphasis on describing data and explaining it well, in the dramatic overhaul of physician drug labeling under the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR: 201.57) promulgated in 2006 (Federal Register 71, No. 15, January 24, 2006). The Agency had originally intended that the Pregnancy and Lactation sections of physician labeling regulations would be part of this effort, but realized these needed an entirely separate line of development and consideration.

-

Eliminate the letter categories as their simplicity is misleading, at best.

-

Employ narrative descriptions of fetal risk and the basis for determinations about that risk, including whether it is based on animal data, human data, or both.

-

Frame risk discussions in the context of background risks of birth defects, and the drug's clinical use, such as whether it is for a serious or life-threatening condition.

-

Include information about dosing in pregnancy, if available.

-

Incorporate relevant, new information in a timely way.

A multidisciplinary working group of FDA physicians from several specialties, pharmacists, toxicologists, and risk communication experts considered these recommendations, and many others, in the daunting task of developing the new proposed rule. Shortcomings of the current labeling model were most clear to the group, but how to meet the expectations set by experts and the public was another matter. We began by taking the patient's perspective and immediately recognized the variety of factors that women and their HCPs must take into account when considering decisions related to medicine use in pregnancy and lactation. This complex and individualized decision-making process belied any hope of communicating risk information in this setting with simple, symbolic depictions. We had the challenge of informing, but not directing, the practice of medicine. Also, as regulators, we knew that some degree of standardization was essential so that product labels could be reasonably compared. The development process took several years following the public hearing and advisory committee meetings, including rounds of focus group testing of obstetricians, nurse midwives, and other HCPs caring for pregnant women, as well as further consultation with outside experts.

NEW MODEL: PREGNANCY AND LACTATION LABELING

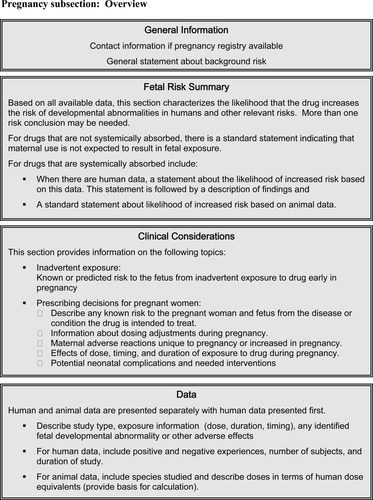

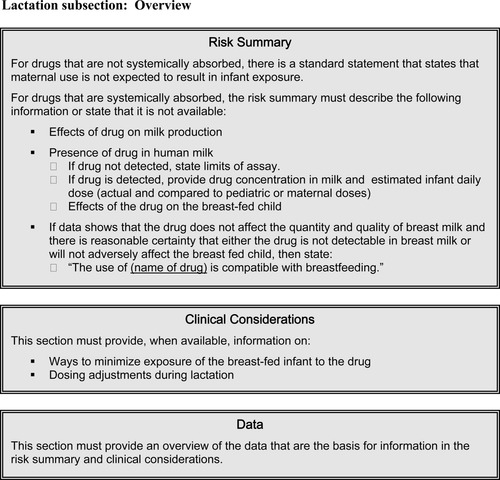

Under FDA's proposed rule, labeling would contain two subsections, one on pregnancy and one on lactation. The five letter categories would be replaced with three components in each of these subsections: a risk summary, clinical considerations, and a data section. These are summarized below and depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

Overview of lactation subsection content.

Overview of lactation subsection content.

PREGNANCY

Before the three major sections of this part of labeling, the proposed rule requires two things. First, if there is an active Pregnancy Exposure Registry for the drug, this would be stated and information about how to contact the registry to enroll provided. Second, a general statement of background risk will appear:

“All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defects, loss, or other adverse outcome, regardless of drug exposure.”

Fetal Risk Summary

The first section, called the “Fetal Risk Summary” would begin with a one sentence risk conclusion that characterizes the likelihood that the drug increases the risk of four types of developmental abnormalities: structural abnormalities, fetal and infant mortality, impaired physiologic function, and alterations to growth. A standardized framework to describe the risk is included in the proposed rule. That risk statement would state whether it was based on animal or human data. In some cases, more than one risk statement or conclusion might be needed to characterize the likelihood or degree of risk for different developmental abnormalities, doses, or gestational ages of exposure.

If only animal data are available to contribute to the risk summary, it would only contain the risk conclusion. However, when there are human data the risk conclusion would be followed by a short description of the most important aspects of that data, including the data's quality and quantity. To the extent possible, this summary would also include how these data reflect what is known about any specific developmental abnormalities that might be associated with the drug: the incidence, seriousness and reversibility of the abnormality, and the effect on the risk of dose, duration, and gestational timing of exposure.

Clinical Considerations

-

Risk to the pregnant woman and fetus from the condition for which the drug is indicated, especially if the condition is not treated.

-

Need for dose adjustment in pregnancy.

-

Adverse reactions associated with the drug that may be unique or uniquely concerning in pregnancy.

-

Any interventions that may be needed to monitor use of the drug or for side effects (e.g., blood glucose monitoring).

-

Potential neonatal complications associated with drug use by the mother, including severity, reversibility, and possible interventions to mitigate them.

-

Effects on labor and delivery—for a drug with a recognized use during labor and delivery, regardless of whether there is an approved marketing indication for such use, the label will include information about what is known about how the drug may affect the mother and fetus/neonate, the duration of labor and delivery, and the possibility of complications to the mother or neonate postpartum.

Data Section

This section of the label will provide a detailed summary of data available to support the previous two sections. Human data would be presented separately from animal data, human data first. The description of the studies would include: dose or other exposure (animal doses given in terms of human dose equivalents), the nature of identified fetal developmental anomalies and other adverse effects and, for animal data, the species used and an explanation of what is known about the relationship between drug exposure and mechanism of action in animals versus humans.

LACTATION

Like the Pregnancy section, the proposed rule outlines a Lactation section composed of a Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, and Data subsections (see Figure 2). In the Risk Summary, if appropriate, a statement may be included that the use of the drug is compatible with breastfeeding. It will also include any information available on the effects of the drug on maternal milk production, whether the drug is known to be transferred into human milk (and if so, how much), and the effect of the drug on the breast-fed infant. Under Clinical Considerations, labeling will provide available information on ways to minimize exposure of the drug to the breastfeeding child, such as through timing of ingestion or pumping and discarding some of the milk. Potential drug effects in the child and recommendations for monitoring or responding to these effects will be described, if known. Also, any information on the need for dose adjustments in lactation will be included. As for the Pregnancy Section, the Data subsection of Lactation will provide an overview of the data upon which other statements are based.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

The proposed rule is just that—a proposed rule. For 90 days after publication, any interested party is invited to comment on any aspect of it through the Public Docket. In fact, there are areas within the proposed rule itself for which we specifically seek comment, including formatting, the content of some of the standardized risk statements, how to quantify terms such as “low”, “medium”, or “high risk”, and better ways to clarify when risk is predicted based on animal data versus characterized by human data. The deadline for comments is August 30, 2008, although, if there is sufficient interest, the Agency may extend the comment-period. FDA will review each and every comment and take it into account in developing a final regulation, or Final Rule. Therefore, the time to a Final Rule will be highly dependent on the quantity and nature of the comments received.

EXPECTATIONS

-

Ensure clear, accessible communication of information to HCPs on the use of drugs during pregnancy and lactation.

-

Facilitate improved care of pregnant and lactating women through well-informed counseling on and use of drugs during these times.

In the longer term, the proposed regulations will raise the scientific bar for types of data and information sought for inclusion in these labeling subsections. Even if the studies are not required by regulation, more and better research will be conducted to address the risks and benefits of medications in pregnant women.

Experience with other changes in labeling regulations has taught us that sound scientific underpinnings to the model and label content are essential. They demand that the pharmaceutical industry, academia, and FDA rise to build expertise in the subject area of concern. To meet these demands will require collaboration across multiple stakeholders to train experts and share them. It is time.

To read the Proposed Rule in its entirety and other rule-related documents, you may visit the following webpage: http://www.fda.gov/CDER/regulatory/pregnancy_labeling/default.htm.

To comment on the Proposed Rule: you many submit comments, identified by Docket No. FDA-2006-N-0515 and/or RIN number 0910-AF11, by any of the following methods, except that comments on information collection issues under the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 must be submitted to the Office of Regulatory Affairs, Office of Management and Budget.

Electronic Submissions

Submit electronic comments in the following way: Federal eRulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the instructions for submitting comments.

Written Submissions

-

Fax: 301-827-6870

-

Mail/hand delivery/courier (for paper, disk, or CD-ROM submissions): Division of Dockets Management (HFA_305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, Rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852.

RADM Sandra L. Kweder M.D.*, * U.S. Public Health Service, Office of New Drugs, Center for Drug Evaluation & Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Rockoille, Maryland.