Community-led investigations of unmarked graves at Indian residential schools in Western Canada—overview, status report and best practices

Abstract

Part of Canadian history that is now being addressed is the legacy of Indian residential schools (IRSs) and closely related institutions. For most of their 200-year-plus history, these were run by various churches or religious organizations, and many were directly funded (and eventually run) by government. Attendance by Indigenous children at these schools was made compulsory, and children were deliberately taken far from their cultural base, native language and family in the name of cultural assimilation. Abundant and longstanding evidence has documented abuse, neglect and high rates of death at the schools. Most or all schools had cemeteries, many of which have fallen into neglect and/or been lost through time. Documenting the numbers, names and burial locations of students who died at the schools has become a national priority. Since 2021, interest in this work has accelerated, due in large part by media announcements of geophysical findings of potential unmarked graves at various school sites. Geophysical surveys for unmarked graves are planned or underway at a large number of school sites nationwide. Related lines of research are seeking to document the extent and nature of student deaths based on archival records, survivor accounts and other lines of evidence. As suggested by government and demanded by Indigenous communities, these searches are being led by the affected communities. This paper represents a snapshot of elements of the work in progress, based in part on the personal participation of the author in multiple IRS searches and resulting direct involvement with local communities. Included in this contribution are a historic context, broad overview of community participation/leadership and suggested refinements to geophysical survey best practices that have been promulgated by the Canadian archaeological community and other nationwide organizations.

1 SCOPE AND PURPOSE

As of this writing (July 2023), a large number of geophysical investigations for unmarked graves are taking place throughout Canada as a part of efforts at national Truth and Reconciliation (e.g., Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a) around the dark past of Indian residential schools (IRSs). 1 This manuscript will include a brief overview of the history and a summary of documented abuses and deaths at the schools, as well as a review of some geophysical searches to date. The author is involved in a number of such efforts. Geophysical investigations at IRS sites are inextricably linked to nearby First Nations communities and to the communities of students who were forced to attend each school. There are many issues involved here, including sovereignty, but a fundamental reason for the necessity of community involvement is that the schools are within living memory of community members and particularly of survivors. This is in marked contrast to more typical archaeological geophysics investigations, in which the original inhabitants are deceased, stakeholders are less emotionally engaged and the sites being investigated are in the more distant past.

Geophysical investigation for unmarked graves at IRS (and related) sites is currently a matter of national focus in Canada, with regular announcements of new discoveries. The recent prominence of these investigations has raised awareness of geophysics, especially GPR, nationally. The vast majority of First Nations community members are unfamiliar with the technologies involved, as are most Canadians in the general public. 2 Moreover, the practice of archaeological geophysics is not as well established in Canada as it is elsewhere, for example, in the United Kingdom and Europe. Therefore, IRS work has included a large education and training effort aimed at the public, communities and especially at archaeologists and related practitioners who are using geophysical methods. These facts, plus the mandate for community involvement, combined with the large numbers of IRS sites to be investigated, all mean that this work is a fast-developing, evolving process.

Having provided the above brief review of the historical context, this paper seeks to provide a snapshot of the work in progress, salient issues and a technical discussion of best practices. This will be necessarily a somewhat personal narrative, with the disclaimer that the author's experience is limited to Western and Northern Canada and is thus only fully authoritative with regard to the approach being followed by communities he is familiar with. However, this knowledge is supplemented on the provincial and territorial level by the fact that the author is serving on the British Columbia Technical Working Group (TWG) on Missing Children and Unmarked Burials (University of British Columbia, 2021) and is a contractor and advisor to the territory-wide Yukon Residential Schools Missing Children Project. At the federal level, the author has been consulted on IRS investigations by members of the National Advisory Committee on Residential Schools Missing Children and Unmarked Burials (CIRNAC, 2022; National Advisory Committee on Residential Schools Missing Children and Unmarked Burials, 2023) and has helped brief federal officials on aspects of IRS searches in British Columbia and Yukon.

This is not meant to be a static report on a fully completed project. Indeed, it is expected by many in the field that full completion of IRS-related work may take a decade or more. In addition, it must be noted that each Indigenous community has different traditions, values and leadership that all combine to shape their approach to IRS searches. Finally, there are differences in legal and regulatory frameworks among the different provinces and territories involved, as well as various possible types of land ownership (e.g., reserve, settlement, Crown and fee simple). Despite the rapidly evolving nature of the work in Canada and the above differences, there are commonalities and many areas of emerging consensus. This paper will be an attempt to summarize those and, it is hoped, will serve as a useful overview of work in progress and provide a revised set of best practices and recommendations for IRS surveys.

2 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

2.1 History of IRSs in Canada 3

As Canada became increasingly densely settled by non-Indigenous 4 peoples in the early 19th Century, an initial interdependent relationship between settlers and Indigenous people gave way to a view by about 1820 that there was an ‘Indian Problem’ in Canada, with increasing attempts to address this ‘problem’ in the civilian realm (Miller, 1996). Full enumeration of colonialist steps aimed at gaining economic dominance in Canada is beyond the scope of this manuscript, as are similarly motivated military actions. Instead, the focus of this section is to outline the parts of the process of cultural domination and especially attempts at ‘assimilation’ that culminated in the eventual government-driven establishment of IRSs. In this regard, ‘Settler Colonialism’ is the term often employed to describe the set of processes that ‘destroy as they replace’ (Wolfe, 2006).

By sometime in the 19th Century in settler Canada, the dominant view of the solution to the above ‘Indian problem’ had become embodied in approaches that focused on cultural assimilation. In brief, this was a racist belief that exposing and converting Indigenous people to the perceived benefits of White Christian culture would ease barriers and friction, not incidentally being economically beneficial to settlers. An early expression of this was the Gradual Assimilation Act of 1857, which predates Canadian confederation in 1867. During the Victorian era, colonial views gradually shifted in favour of a more clearly hard-nosed, negative and explicitly racist perspective (e.g., Francis, 1998) towards Indigenous populations. One manifestation of this attitude shift was the language and provisions of the 1876 Indian Act and its many later amendments (partial summary in Hinge, 1982), 5 which was in part an effort to limit or eliminate First Nations' sovereignty and in other respects was aimed to destroy Indigenous culture by forcibly merging it into that of the settlers.

Indian schools (and the notion of assimilation) had origins in the early 17th Century, with Catholic mission and other religious schools (Miller, 1996). Missionaries brought with them the view that native culture was immoral and improper, and Christian religious zeal was behind many of the attacks on native culture, beliefs and practices that intensified over time (Ray, 1997). During the 19th Century, the idea took hold in settler society that children, being more manageable, held the key to assimilation and thus the use of schools to achieve this aim became increasingly widespread.

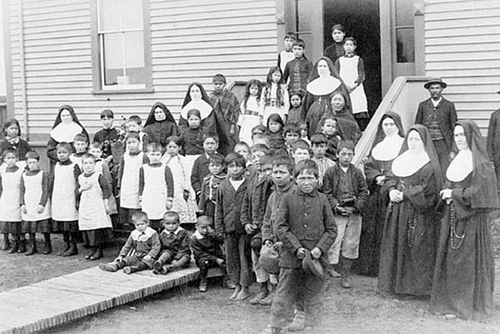

By the 19th Century, most if not all schools and institutes that focused on Indigenous assimilation had Christian religious origins, either explicitly or in principle. One well-known early illustrative example was the Mohawk Institute, which was founded in 1828 as the Mechanic's Institute, by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England, in what is now Ontario. In its various locations and buildings, this was the longest-running residential school in Canada, only fully closing its doors in 1971 (National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, 2023). The history of the Mohawk has parallels that of other IRSs and with the broad outlines described below, including government funding and eventual takeover, systematic abuse, student deaths and more (Figure 1).

(Source: archives Canada).

Further hardening of the 19th Century approach to assimilation was manifest in 1883, with an amendment to the Indian Act (Hinge, 1982), that formally established the IRS system under supervision of the Department of Indian Affairs. Schools were explicitly designed to isolate children from their languages, families and culture, in an effort to ‘take the Indian out of the child’, a quote from John A Macdonald, first Prime Minister of Canada, whose statement in reference to schools (in 1879, while serving as Superintendent of Indian Affairs) illustrates IRS system intentions:

When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with its parents, who are savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly impressed upon myself, as head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.

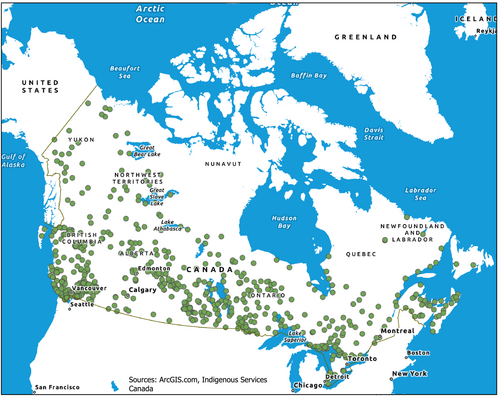

IRS attendance became compulsory nationwide under the Indian Act in 1894, with strengthening of the requirement in 1920. Peak enrollments were in the 1920s and 1930s. Determining the exact number of schools that Indigenous children attended is somewhat problematic, as is estimating the number of students. One frequently cited count of residential schools is 139. However, these are schools that were covered by the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) and that received full or partial federal funding; furthermore, that number has been expanded since 2007. Figure 2 shows locations of IRS sites covered by the IRSSA as later expanded. However, as noted above, some schools received provincial or church funding only (Hansen et al., 2020) and may not be covered by the IRSSA. In addition, the number of facilities aimed at assimilating Indigenous children also includes day schools, dormitories and hostels, as noted above. Sites that did not receive IRSSA recognition for various reasons but that are still the focus of current or planned searches currently number 62 (Canadian Geographic, 2023). One frequently cited estimate is that more than 150 000 children attended over the duration of the IRS system (Miller, 2012); however, this number may never be determined precisely.

Beginning in the 1950s, there was an effort to move away from the IRS system and phase out the schools, although progress was episodic and not necessarily beneficial to the children involved (Hansen et al., 2020). The federal government formally took over direct administration of IRS schools (as opposed to pass-through funding to churches) and the last school closed in 1997. However, the legacy and emotional impact of the IRS system continue to the present, as will be outlined below.

2.2 Abuse, deaths and investigations

Systematic abuse, neglect, mistreatment, disease and attendant student deaths at IRS schools have been documented for nearly the entire duration of the system (e.g., Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a). Perhaps the most prominent, but not the first or only, exposé of disease and death at IRS schools was undertaken by Dr. Peter Bryce on behalf of the Department of Indian Affairs in 1907. Based on site visits and surveys of school administrators, Bryce documented extremely high death rates estimated at 42% among IRS students (Bryce, 1907). Bryce's report was disregarded, and attempts were made to silence him. Bryce went on to publish a book summarizing his findings, discussing in addition his own forced retirement from the federal government (Bryce, 1922).

Dr. Bryce reported that the majority of student deaths were due to tuberculosis and that many such deaths could have been prevented with adequate medical care. Abundant indications from school inspectors, medical officials, school administrators and others pointed to a systematic pattern of student deaths spanning the entire history of IRSs, due to overcrowding, disease, malnutrition, physical abuse/neglect and more (e.g., Mosby & Millions, 2021; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a). This was all consistent with the increasingly hardline approach to assimilation taken by government and school officials noted earlier. In addition, at least six residential schools were sites of long-term experiments on the effects of malnutrition on children, conducted without consent and subsequent to the 1947 publication of the Nuremberg Code of experimental research ethics, which was drafted in response to Nazi atrocities at concentration camps (Mosby, 2013).

Deaths at the schools meant that they often needed to have cemeteries, and these are often a primary focus of geophysical surveys. However, finding them and even acknowledging the existence of such cemeteries can be problematic. Cemeteries at residential schools would be expected in this era of higher child mortality and greater incidence of epidemics. Further, the ages of children at residential schools ranged from just above toddler to late teens (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a), and by 1894, all Indian children (as well as many Métis and Inuit) were required to attend, with the number of schools and students peaking in the 1920s. Therefore, residential schools at their peak held the great majority of Indigenous children across a broad spectrum of ages, in abusive conditions that were problematic to survival at best. Thus, cemeteries are expected to be ubiquitous, if not universal, at residential schools and are a part of the emerging body of evidence of IRS abuse and deaths.

As summarized by Hamilton (2015), there are many reasons that finding cemeteries associated with IRS sites may be challenging. These include poor or non-existent record-keeping, the disorganized state plus great scale and wide extent of archival evidence, lack of proper cemetery registration, age and deterioration of grave markers, overgrowth by vegetation, fading of cemetery locations from memory and more. In addition, it is clear from survivor accounts that in many cases burials and grave locations were clandestine. Many cemeteries that have been identified are abandoned, obscure and vulnerable to vandalism (Hamilton, 2015).

Termination of the IRS system in the mid-20th century was driven in part by a growing realization in the modern era that severe abuse was built into and widely associated with the IRS system. Specific and comprehensive examination of all aspects of residential schools started at the government level during the 1980s and 1990s as part of investigations that went into formulation of the IRSSA. Investigation continued with the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996) and with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which called the IRS system an example of ‘cultural genocide’ and estimated that a minimum of 3200 students died at the school (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a). However, it has been argued repeatedly that the number of student deaths is likely far greater, due in part to the cemetery problems outlined above and also due to poor record keeping, all coupled with financial and other disincentives for school officials to report student deaths. The TRC conducted numerous interviews with IRC survivors; these and other lines of evidence (including that summarized above) indicate that student graves are to be found at most if not all IRS sites.

2.3 History of geophysical surveys for unmarked graves in Canada

Prior to the current wave of IRS investigations in Canada, the use of geophysical methods, particularly GPR, for detecting unmarked graves was well established outside of Canada (e.g., Bevan, 1991; Conyers, 2006, 2013; Dalen et al., 2010; Davis et al., 2000; Doolittle & Bellantoni, 2010; Gaffney et al., 2015; Goodman & Piro, 2013; Schultz, 2012) and many others. Within Canada, examples of non-IRS geophysical investigations of unmarked graves are much less plentiful and include Lafferty et al. (2021), Nelson (2020) and Wadsworth et al. (2020, 2021). The scarcity of published examples of geophysics for unmarked graves in Canada is consistent with the author's perception that archaeological geophysics in Canada is not as commonly used as elsewhere, although that is clearly changing in the IRS era.

The TRC issued 94 strongly worded Calls to Action that included a section with specific recommendations for initiatives under the heading of ‘Missing Children and Burial Information’ (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015b). Despite the abundant evidence and clear response demanded by the TRC, movement in terms of large numbers of subsurface investigations did not follow immediately, likely for complex reasons. There were evidently some early cultural-resource management-type geophysical surveys that predated the TRC report and that were not widely publicized, if at all. One early project was an investigation and GPR survey for unmarked graves begun in 2012 at the site of the Brandon Indian Industrial School in Manitoba (Nichols, 2015). This did receive media attention (e.g., Quan, 2015). One prominent researcher who carried out IRS-related work prior to 2021 was Dr. Kisha Supernant and associates at the University of Alberta (University of Alberta, n.d.).

A very highly publicized announcement of geophysical survey results indicating unmarked graves at a residential school came in 2021, when the Tkʼemlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced finding 215 (later revised to 200) GPR-based features that were inferred to be unmarked burials associated with the Kamloops residential school (Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc, 2021). Since that time, many more geophysical investigations of IRS sites have been initiated and more are in the planning stages throughout Canada. As of the date of this manuscript revision (July 2023), the author is directing IRS geophysical investigations at nine sites in Western Canada (multiple sites in British Columbia, one current and a further seven to eight sites planned in Yukon Territory, one in Alberta and one in Northwest Territories). The total number of investigations currently taking place throughout Canada is very hard to estimate but may be in the dozens.

3 OVERALL SCOPE OF IRS INVESTIGATIONS

There is much more involved in Truth and Reconciliation efforts around residential schools than just geophysical surveying. Important and needed work is being done in regard to legal, law-enforcement, mental health, educational, privacy, sovereignty issues and more. Most relevant to geophysical investigations is the need to identify specific areas to survey at IRS sites, which can be quite large. In process or planned are archival research into deaths at government, church and other facilities as well as gathering of school-survivor accounts, including those of families of survivors and community witnesses. There have also been efforts to locate and interview former teachers, clergy and other school officials. Beyond identifying potential survey locations, a major objective is to determine the names and the numbers of missing children.

Research efforts are hampered by a number of factors. For one, the IRS model was to remove children from their communities, language and families to attend the schools (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a). In many cases, a local IRS would have housed students from dozens of First Nations located far from the actual school location and few to none from the local community. This was part of the IRS design to break down Indigenous culture, and the result for IRS research now is that communication and coordination of search efforts is often quite difficult. Another hindering factor is that archival records may be scattered—some were gathered by the TRC and may now be housed with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, n.d.), while others may be found in church, federal, provincial or territorial archives, or not at all. There was no incentive or particular requirement to keep accurate records of student deaths during the duration of the IRS system, and in fact, there may have been incentive to keep a missing or dead child on the roster of a school because federal funding was allocated on a per-capita basis (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a). Finally, research based on survivor accounts is hampered by the advancing age of the survivors, the imperfection of memory and by the fact that discussing their IRS experience is likely to re-traumatize survivors who are part of a long-lived pattern of intergenerational trauma (e.g., Bombay et al., 2014).

4 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT PARTICIPATION

Several federal-level organizations and agencies are participating in the IRS search process. For example, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (n.d.) serves as a clearinghouse for information and support nationwide, is a primary resource for communities leading searches and is helping oversee and support implementation of the TRC Call to Action in regard to Missing Children and Burial Information (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a, 2015b). In 2017, the government announced the dissolution of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and its replacement with the departments of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC, 2022) and the Department of Indigenous Services. More recently, the federal Ministry of Justice appointed a Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with IRSs, with a mandate that includes ‘… identify[ing] needed measures and make recommendations for a new federal legal framework to ensure the respectful and culturally appropriate treatment of unmarked graves and burial sites of children associated with former residential schools’. (Office of the Special Interlocutor, 2023).

The principal federal funding agency for all aspects of IRS searches, as well as for mental-health support and other relevant activities, is Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC). CIRNAC representatives in each province and territory work directly with Indigenous communities in funding IRS searches, and currently (July 2023), at least CDN $270 M has been allocated at the federal level. It appears likely that more funding is to be provided. Some if not all provinces and territories are also assisting with funding and coordination. Federal and provincial/territorial archives, coroners' offices, libraries, universities and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) all have staff and resources allocated to supporting IRS searches. There are also a number of other groups and organizations dedicated to supporting IRS searches, too numerous to name here.

5 INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

5.1 Mandate and jurisdiction

The working relationship as it presently exists among NCTR, CIRNAC and Indigenous communities (and other funders and stakeholders) is that the communities take the lead in IRS investigations. In the author's experience in British Columbia, this means that the First Nation located closest to (or that contains) an IRS site takes the lead. This is also the case with the Northwest Territories investigation; there is also engagement with territorial and local Métis communities there.

In Yukon, the model is different, influenced in part by a somewhat different history, IRS structure and government-school relationship there. The Yukon Residential Schools Missing Children Project (YRSMCP) is an initiative of the Council of Yukon First Nations (Council of Yukon First Nations, n.d.). The YRSMCP is territory wide and is intended to represent all 14 Yukon First Nations with two members from each Nation, usually IRS survivors. The YRSMCP helps serve as government liaison and resource coordinator for IRS-related research territory wide. This facilitating role is needed because of the far-flung, remote nature of many Yukon sites and communities and allows for centralized archival research, survivor interviews, mental-health support and more. For planning work at a specific IRS site in Yukon, an executive committee is formed, comprised of a subset of the YRSMCP and an executive elder from the local community. This working group then collaborates with the local community to develop a specific search approach, guidelines and protocols that are relevant to the values, needs and traditions of the community. Because this model of community involvement differs from that elsewhere in its approach and scope, federal government and especially CIRNAC has paid particular attention to the IRS search process in Yukon, and the Special Interlocutor and her staff recently helped facilitate a two-day Gathering in Carcross Yukon to share information and raise concerns around the IRS research process. The approach being developed in Yukon will also be relevant to the other northern territories, Northwest Territories and Nunavut (Figure 2).

In provinces without Métis or Inuit presence, determination of the lead community responsible for organizing and executing a local IRS search can be fairly straightforward (cf. Figures 2 and 3). For example, in the case of a residential school being situated on reserve land of a First Nation, that nation takes the lead. This is by far the clearest case of jurisdiction. Absent such a reserve–IRS site relationship, often the nation sited closest to the school in question takes the lead. In addition, the size and resources available to a particular nation may play a role in assignment of jurisdiction. In all cases, jurisdiction must be asserted and worked out by negotiation among nations. Based on the author's observations in the case of British Columbia (BC), jurisdiction and assignment of First Nation lead communities have been worked out. In the Northwest Territories (NT), jurisdiction issues are complicated by the presence of significant Métis and Inuit populations who are stakeholders, in addition to numerous First Nations. In the case of at least one NT school site, the investigation is being run by the nearest First Nation to the site, in consultation with the local Métis community. It remains to be seen how jurisdiction will be worked out for other IRS sites in NT.

5.2 Search process

As mentioned, some of the following is based on the author's personal experience and observations, with the caveats also mentioned above. Due to the highly sensitive nature of this work to the communities involved, no specific school names, communities or places are identified.

Primary goals of IRS searches are to identify the locations of unmarked graves that may be associated with particular school sites and to compile names of students who did not survive. After assignment of a lead community and acquisition of federal (and provincial/territorial if relevant) funding, the project typically begins with local community outreach and meetings. Most if not all communities have elders who are school survivors, and the sentiments of these people are held in utmost regard. Counselling and mental-health resources are generally sought, funded and put in place before community discussions on IRS topics begin.

After community meetings, chief and council (or designated others within the community) usually formulate a plan of action to begin the work. Most often, this will involve assigning project management, although First Nations may not all have the capacity to make use of internal personnel to manage an IRS search. A frequently expressed preference is to hire local community members, but this is not always possible. Barring that, management candidates may be found among nearby Indigenous community members. In some cases, project managers may be non-Indigenous. The work of chiefs/councils and project managers is quite often assisted by various federal, provincial or territorial government entities, as well as the very important assistance provided by faculty, grad students and staff at universities too numerous to mention; in addition, there may be regular meetings among various lead communities to share information. For example, in BC, there are regular province-wide gatherings of lead communities and a TWG tasked with providing guidance to communities in matters of ground search, background research, data-sharing, data sovereignty and more.

Survivor interviews are one of the most important (and delicate) pillars any IRS search. All survivors report traumatic experiences at the schools, so care must be taken not to re-traumatize those who choose to speak about their time at the schools. Interviews are often conducted by trained Indigenous people, and in all cases, mental-health support is available. One main objective of interviews is to prioritize specific locations for geophysical surveys, as at many school sites the potential area of unmarked graves will be on the order of hundreds of hectares. Depending upon the approach chosen by the community and project management, may be shown photographs, maps, aerial images, lists of student names, 3D GIS-based reconstructions and more, all in an effort to obtain leads on where to search the ground. As many survivors are elderly, conducting survivor interviews is a matter of urgency yet must be conducted very sensitively. In many cases, the decision is being made not to burden elders with the need to recall such a traumatic time in their lives,

In parallel with survivor interviews, two other lines of investigation are always undertaken, again with a primary objective of determining specific areas of ground to search. One of these is the search through written archives. Relevant resources for this may be found at federal, provincial/territorial offices/archives, in church records (perhaps even in Rome), community records, at law-enforcement facilities, with coroners or in other possible locations. Along with possible ground locations, a main outcome of archival-records searches are lists of names of students who attended, particularly any death records or indications of the missing (many families never received any official notice of why their child never returned from a school). The other universal research that is specifically focused on likely ground locations is the acquisition and analysis of old maps, aerial photos, plans and other spatial representations of IRS sites over the time frame of their operation. As with the written records, there are a quite a number of possible sources to be searched.

Two other tools aimed at identifying potential ground to search are common but not universal. One that is being used at 100% of the IRS sites in the author's experience is laser-based Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR). Bare-Earth models derived from LiDAR can reveal grave-related depressions and mounds that may not otherwise be visible. This is particularly true in the case of areas with tree canopy. Resolution requirements are such that a very high point density on the ground is needed, which generally means flying the LiDAR from a UAV/drone at low altitudes and fairly slowly, of course using a high-resolution scanner. Manned, fixed-wing based LiDAR and existing off-the-shelf government LiDAR products have proven unsatisfactory to the resolution needs of IRS searches. The final tool that may be used to facilitate IRS searches is the Traditional Use Survey (TUS). These may have some overlap with survivor interviews and have the specific goal of understanding land use by Indigenous people in the past. In areas surrounding IRS sites, TUS information may reveal information on cabins, huts and other built features from the past (potentially including lost cemeteries) that can help focus ground searches. A TUS may be particularly useful for larger study areas.

5.3 Capacity development

Being community-led and community-driven means that many First Nations are keenly interested in performing geophysical survey work for themselves. Others prefer to ‘leave it to the experts’ at least initially, while working on long-term strategies for increase technical capacity in the community (Chief Waamiiš Ken Watts, personal communication, 2023). For those wishing to develop the skills needed to successfully perform geophysical surveys at IRS sites, efforts are being made to develop training courses and financial incentives for Indigenous university students to pursue archaeological geophysics as a career. In BC, Dr. Andrew Martindale of the University of British Columbia has partnered with the Musqueam First Nation for a GPR training course focused on IRS searches (GPR Course for Indigenous Communities, 2023). As of this writing, GPR training in BC has progressed through general theory and background, survey design and survey execution, with processing and interpretation modules or a separate course under development. A later section of this manuscript will discuss resources and challenges available to communities that are being used for capacity development.

6 GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY

As outlined above, multiple lines of evidence may be considered in planning geophysical survey for unmarked graves. In the case of smaller sites (such as a single known cemetery), it may be possible to cover the entire area of interest without much reference to the above research results. However, the larger the potential area of interest, the greater the importance of the above lines of evidence. In most cases, the above background research is an ongoing process, so geophysical survey is envisaged as a multi-year process, with early stages focused on the most obvious search locations (e.g., those closest to the school site). The development of additional priority areas to search is then incorporated into later years' work plans. The author is currently directing execution of a third year of survey at one IRS site and a second year at two additional locations, with no obvious end in sight at any.

A key element of geophysical work at IRS sites is communication with the lead community, before, during and after the survey work. Prior to the start of fieldwork, local communities typically request live presentations that explain geophysics and how it will be used. This needs to be aimed at a general audience, and the author has had good feedback from simple, non-digital presentations that rely on photographs passed around the audience. Two levels of presentation may be made—one to survivors and the other to survivors plus the local community. In either case, it is important to set expectations properly by explaining what geophysics can and cannot do. To combat media misinformation is imperative to explain that there is no such thing as a geophysical ‘bone detector’ and that geophysics cannot find all the missing. This is a very challenging discussion, to say the least, both for the presenter and the audience.

After fieldwork, processing and interpretation are complete more presentation(s) need to be made with results. Again, this needs to be framed for a general audience and very sensitively handled. It is essential in this presentation to give the audience some sense of how the interpretations were derived and the degree of uncertainty involved. Typically, exact locations of suspected graves are not shown, out of deference to cultural and emotional sensitivities; these are however detailed in a written report and maps made available only to designated people. There are typically three to five levels of information presented: (1) project directors and other inner circle (local chief and council) receive the greatest level of detail; (2) survivors; (3) larger local community; (4) regional chiefs and councils; and (5) general public/media. In general, the geophysics manager will present directly to the inner circle, allow them time to digest and then may take a more secondary role in the other presentations, allowing local community members to lead. This is entirely consistent with the community-led nature of these projects. It is important to stress that the media/general public announcement needs to be very carefully crafted, to avoid sensationalistic news accounts of ‘bodies’ or ‘mass graves’ being found. In addition, news media tend to fixate on numbers of potential graves, which can be mediated to some extent by a clear presentation of levels of certainty (or lack thereof). It is also important to carefully distinguish numbers of suspected graves found using geophysics from estimates obtained from other research such as archival searches. Social media has been a source of misinformation derived from local community members, so messaging at all levels needs to be carefully considered and managed.

6.1 Resources for communities and practitioners

Geophysical theory and practice can come with steep learning curves for those seeking to use such methods for archaeological prospection and especially for unmarked-grave detection. This is true for archaeologists, who generally do not receive formal training in geophysics as part of their curriculum, and even more true for First Nations communities leading IRS searches. Fortunately, several compendia of geophysical (and other) guidelines and best practices have been developed that are proving helpful to practitioners and communities. One of the more comprehensive of these is from the Canadian Archaeological Association Working Group on Unmarked Graves (2023), which was in turn influenced by the European Archaeological Council guidelines (Schmidt et al., 2015).

A number of other useful and general resources have been made available to help communities and practitioners understand, plan and conduct geophysical surveys (primarily GPR) for unmarked graves at IRS sites. These include material from the NAC (National Advisory Committee on Residential Schools Missing Children and Unmarked Burials, 2023); Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology (2021); Indigenous/Science (2023); Brglez (2022); Wadsworth (2022); Kane (2022); Simons et al. (2021) and others. In addition to the above online resources, groups aimed at helping practitioners and communities with their search processes include the Canadian Archaeological Association Working Group on Unmarked Graves, Geophysics for Truth, Alliance to Support Indian Residential School Missing Children Investigations and others. Within the province of British Columbia, the author was invited to become a member of and has contributed regularly to the British Columbia TWG on Missing Children and Unmarked Burials; membership in this includes representatives from all BC First Nations conducting or planning IRS searches, as well as prominent technical experts in a variety of fields. This group meets monthly online and at least biannually in person. As previously noted, the federal government has established the office of the Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with IRSs, with a broad mandate to facilitate and enhance the IRS search process before, during and after ground survey.

6.2 Best practices

As summarized above, there is considerable help available for field practitioners new to geophysics and for communities engaging in IRS searches, and one important outcome of the above-described guidelines is the formulation and adoption of sets of best practices designed to be accessible to those new to geophysics. It is worth noting that there is no government licencing or accreditation required to practise archaeological geophysics in Canada, so accuracy and completeness of best practices is particularly important to IRS searches.

The author and his team collectively have over 60 years' experience in near-surface geophysics and credentials among our group include a PhD, two MS and two BS degrees in geophysics, as well as the author's earned MCIfA 6 credential. Grounding in geophysical theory, as well as abundant experience, have resulted in an approach to archaeological geophysics survey design, processing and interpretation that considerably predates the present wave of IRS work in Canada (e.g., Whiting et al., 2001). Moreover, in regard to GPR survey for archaeological objectives, principles of survey design have been well established for even longer, at least 25 years (e.g., Conyers & Goodman, 1997) and are based on even longer-established concepts relating to near-surface geophyscal survey.

The best practices and survey guidelines that the author and team use for IRS searches are in some instances similar to the above-referenced list of best practices but predate them (as noted) and in several instances our approach differs from recent detailed compendia of best practices (e.g., Canadian Archaeological Association Working Group on Unmarked Graves, 2023). Canadian Archaeological Association (CAA) guidelines are very user-friendly and accessible and provide very useful starting points for communities and practitioners undertaking IRS searches. Basic principles of geophysics and of designing a successful near-surface geophysical survey are taught in geophysics courses (and most importantly learned through long experience), so the convergence between the author's methods and much of the content of recent best-practices compilations should be unsurprising—a best practice is that because it is a proven adaptation of methods to the particular challenges posed by the physics of target detection in particular ground conditions and a particular depths. One important caveat is that a best practice never be viewed rigidly, in cookbook fashion, as every site differs. 7 More on this below.

- Experience matters. We view specific, prior training and experience in archaeological geophysics as mandatory. As mentioned, Canada has not had a long or rich history of widespread use of archaeological geophysics. One may regard CAA guidelines as a solid, general-purpose ‘cookbook’ with great usefulness. However, the array of possible ‘ingredients’ (equipment types, site conditions, survey objectives, depths, soil types, potentially troublesome position-keeping, variable burial practices, etc.) is tremendously variable, which requires agile and informed modification of ‘recipes’ in many cases. Even with best intentions and the CAA guidelines in hand, an IRS search is not the place to practise archaeological geophysics for the first time. Communities are counting on the reliability and accuracy of results. Without a solid base of training and experience, an obvious pitfall of relying on a cookbook approach is that a survey may be unsuccessful or produce misleading, inaccurate results. Even a geophysical background based in mining, environmental, engineering or utility locating may not necessarily be sufficient or adequate to successfully execute a highly challenging archaeological geophysics survey.

- Always perform a LiDAR survey or at least derive a detailed terrain model from drone photogrammetry. Benefits to this include a highly accurate basemap (as of the survey date) for field planning as well as for results. In addition, subtle terrain variations that may indicate graves may not be evident to personnel on the ground. Moreover, the ability of LiDAR to penetrate vegetation canopy and generate a bare-earth model can be instrumental in guiding searches. This is recommended as a standard practice in all IRS searches, except possibly those confined to small, known cemeteries.

- Start with a known cemetery if possible. In order to asses local ground conditions and instrument response to known burials, it is recommended to gather at least one or two survey grids in a known cemetery and immediately work through processing and interpretation before proceeding with the rest of the IRS survey. A cemetery calibration run like this may result in important modifications to instrument settings and/or survey design that might otherwise not be realized. In addition, it appears to have been common for local community cemeteries to be used for IRS student burials, so due diligence suggests surveying these obvious areas first.

- Consider dual-frequency GPR. Most major GPR manufacturers now offer dual- or even triple-frequency, single-channel GPR instruments. Representative frequency combinations include 200/600, 250/700 and 400/800 MHz. The newest and best of these also feature variously named schemes of stacking signals, with the aim of improving signal-to-noise and increasing depth of penetration. 8 If using single-channel GPR, collecting data simultaneously in a second frequency range has significant advantages. In brief, it can be a best-of-both-worlds scenario, with deep coverage but reduced resolution in the lower frequency and greater resolution but reduced depth in the higher frequency. Due to the great variability in site conditions, ages of graves and burial practices, having the flexibility afforded by two frequencies can improve results markedly.

- Improve survey resolution by making use of multi-channel GPR (MCGPR; Figure 4) if possible. A typical multi-channel instrument collects eight or more channels of data simultaneously, with 8–9 cm spacing between channels. This is considerably higher resolution than the 25 cm transect spacing recommended by the CAA and can yield particular benefits in detecting small graves of unknown compass orientation. In addition, a typical MCGPR collects data in a wider swath and thus is faster on the ground; in open areas, it is also possible to tow MCGPR behind a vehicle, further increasing survey throughput.

- Always use multiple methods. Due to press coverage of the IRS issue, ‘GPR’ has become synonymous with geophysics in Canada, and GPR is what communities ask for in considering an IRS search. However, GPR does not work well in all locations, and while it can be excellent for delineating depth and structure, it does not yield clear information regarding material properties or past use. In addition, GPR data are slow to acquire and process, and it is challenging for inexperienced users to process and interpret. The author's opinion is that GPR should be supplemented by at least one additional method, often as a reconnaissance tool, as discussed further below.

- Scale methods up appropriately for the area to be investigated. CAA guidelines as written are most appropriate for surveys of relatively modest scope, and it may be difficult to scale these guidelines up to for IRS survey areas that encompass larger areas. For example, it would likely be impossible to perform a single-channel XY-direction GPR survey over an area greater than 10 ha in a single field season. For larger areas, determining priorities for coverage based on community input and using all other means is essential. A non-GPR method may be used as a reconnaissance tool that can cover ground much faster than GPR and that also is faster to process and interpret. For example, a multi-channel magnetic gradiometer is roughly 4–6 times faster than GPR and can yield important information about (for example) ground disturbance, subsurface metal, as well as burned-ground burials (practised in Northern areas, where ground was fired to ease grave digging in frozen ground or permafrost). Electromagnetic (EM) survey is also recommended on occasion, as it is also fairly fast to acquire and process, and EM works where GPR does not (i.e., in high-conductivity, clay-mineral rich soil). Relatively fast, non-GPR methods can be used to help prioritize areas to cover with GPR and can help provide additional certainty as to the nature of detected subsurface features.

- Use high-accuracy positioning methods. Three salient aspects of IRS searches argue for highest-possible accuracy in spatial positioning: One is the likelihood that some potential graves will be archaeologically tested or excavated and/or fully exhumed, so accurate positions are critical. Related to this is the fact that some IRS searches may take a forensic turn, with discussion underway in some communities of involving the RCMP and/or coroner's offices. In addition, even absent forensic investigation or archaeological testing, communities may well want the locations of suspected graves marked accurately. Therefore, RTK-quality GPS is recommended, with actual accuracy of at least 10–15 cm. Preferably, geophysical instruments should be connected to external RTK GNSS receivers, and position data should be synced with geophysical measurements. CAA guidelines as written may be read as discouraging the use of RTK GNSS while collecting GPR data due to possible radio-modem interference, and this is certainly something to watch for. However, many RTK GNSS setups do provide a choice of radio frequencies. Another consideration is that poor GNSS (in reality anything other than consistent GNSS ‘Fixed’ positions) will cause apparent wander and even crossover of GNSS/GPS track in map view, even when one is quite certain the lines in the field were straight. Such wander or crossover will severely compromise map-based (depth slice) interpretation. Finally, a GNSS instrument with built-in tilt correction can be extremely useful in removing apparent track wiggle caused by uneven ground and working on hillsides. In areas with poor GNSS coverage or high multipath, a robotic total station is recommended for positioning. A traditional, tape-measure-based grid, even with very accurate grid corners, should only be considered as a last resort, and then, the positions of suspected graves should be considered as approximate only. In the author's experience, consistently accurate positions are almost as important as good survey design and, in many cases, can be more difficult to achieve.

- Process and interpret promptly and carefully, according to clear logical steps. Geophysical data processing is part art and part science, with success dependent on user skill and experience. In inexperienced hands, artefacts can be introduced into results or useful information content may be lost. In addition, delineating correct subsurface depth and geometry in GPR data requires careful migration (conversion of time to depth). In addition, taking the envelope of positive and negative GPR amplitudes by Hilbert transform is useful, as this step essentially takes the absolute value of amplitude. For interpretation purposes, we recommend clearly defined, objective criteria for potential grave identification, and this should be based on both map-view (size and shape) and cross-sectional considerations such as grave shaft presence and any internal reflections (see also Martindale et al., in press). For formal cemeteries, map-view depth slices can be strikingly easy to interpret, but this is often so because burial practices there were not designed to be secret and the graves were not for children. Careful, line-by-line analysis of profile (B-scan) data is frequently needed for complete interpretations. It is also useful to assign at least two levels of certainty to potential graves, based on how many objective criteria are met. In addition, it is suggested that two or more independent interpreters agree before final identification of a geophysical feature as a suspected grave. Finally, there is nothing to be gained and much to be lost in delaying processing for any appreciable time after fieldwork. It is strongly suggested that each day's data be passed through at least some processing and visualization right away. Otherwise, any flaws in survey design or equipment malfunctions may be missed, and it is possible that an entire survey may be ruined if problems go undetected for too long. As noted in the CAA guidelines, survey design can be learned relatively easily but learning to process and interpret geophysical data take much more time and effort. Moving ahead too quickly with surveying without at least a basic processing and interpretation workflow in hand is not recommended.

- Use GIS. All geophysical processing software is capable of generating georeferenced data suitable for import into GIS. And with proper RTK-based data collection (along with attention to potential datum-shift issues and other accuracy matters), layers from different sources may be readily overlaid for interpretation. It is essential to consider interrelationships among different geophysical data sets, along with orthophotography and LiDAR data. If available, location-specific information from survivors and archival records should be assessed in relation to the other data sets. In addition, maps and aerial photos from the past should also be considered in relation to the other data sets. Finally, in IRS searches of large areal extent, GIS modelling or analysis 9 may be used as a predictive tool to plan ground searches, especially in cases where survivor info and archival data are still being gathered.

6.3 Technical challenges

There are abundant challenges on the technical front. It is likely that most practising geophysicists with experience in cemeteries would agree that detecting unmarked graves, especially older ones, is difficult. This is due in large part to factors such as the fact that human remains cannot be imaged directly, preservation may be poor, grave-shaft infill is the same material as the undisturbed surrounding soil, coffins may not have been used and more. In the case of IRS sites, the potential clandestine nature of graves means that the search is much more of a ‘needle in a haystack’ problem than in formal cemeteries, with unpredictable compass orientation and smaller grave size, as noted above.

In addition, geophysical investigations are also inhibited by external factors. One is the historically low use of geophysics for archaeology in Canada noted above. This is probably due in large part to the general lack of regulatory requirement for archaeological investigations that could employ geophysics. Thus, finding skilled companies and practitioners for IRS searches can be difficult. Few universities in Canada have formal programmes in archaeological geophysics. These factors have a negative impact in many ways, including the skill of people and firms available to perform the work, as well as the fact that limited expertise is available to assist in Indigenous capacity-building efforts. An additional challenge facing communities seeking qualified geophysical help is the absolute lack of credentialing. Various provinces have credentials for engineers, geoscientists, archaeologists and so forth but few for geophysicists and none for archaeological geophysicists.

7 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

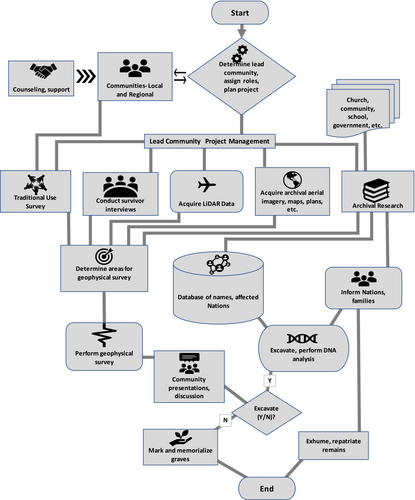

Figure 5 summarizes the author's overall view of the emerging consensus as to the steps and interrelationships involved in a typical IRS search and includes views on best practices and some options that may not be followed by all communities. As discussed above, the local community with jurisdiction takes the lead in the search, although there is normally room for input from affected other communities (i.e., those whose children were sent to the school under consideration). It is important to emphasize that different communities will have different leadership styles, values, traditions and even languages, so each community conducting an IRS search will likely have different priorities and the framework below may differ accordingly.

Another point worth emphasizing is the fact that several of the processes shown in Figure 5 are iterative or at least ongoing. For example, in many cases, ground searches commenced before survivor interviews began and subsequent field seasons' focus areas are likely to be prioritized based on emerging survivor accounts. In addition, archival research is an ongoing process of discovery, and those results may also affect the planning of field investigations. Finally, names and community associations derived from archival research are expected to be complemented in some cases by DNA evidence from the graves being discovered.

The subject of DNA testing and possible exhumation and repatriation of remains is a very difficult topic. Many Indigenous communities abhor any disturbance of human remains and may instead choose to mark and memorialize potential graves identified with geophysics. On the other hand, there is a strong sentiment among community members in some locations to ‘bring the children home’. Part of the author's task in working with communities is to educate them about the nature of geophysics and its uncertainties, in hopes that this knowledge will help inform these difficult types of decisions.

It is repeated often in the communities planning and executing these projects, and among those of us helping, that we are writing the book on how to do this sort of community-driven work as we go. Here in BC, several communities are ready into their second or third year of IRS searches, while other communities are not as far along. The advantage is that the early starters are able to provide guidance to those starting later and as mentioned above, BC has a formal mechanism for information transfer among the communities. All that said, the ‘roadmap’ portrayed in Figure 5 is a generalized snapshot in time of how communities are proceeding. It is to be expected that these processes and consensus as to best practices will evolve over time. Given that this work is expected to take place nationwide over as much as a decade, it will be important to check in from time to time and assess what is new and what may have changed, all in the name of helping lend structure and framework to what is to these communities a very fraught, emotional and complex endeavour.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express first of all my acknowledgement of the emotionally and logistically challenging nature of the work that all communities are undertaking in their IRS projects. In particular, I am very thankful for the deeply satisfying partnerships that have developed over the past year with various First Nation members and leadership. I am gratified by the warmth and acceptance that I feel when visiting and presenting. It is particularly humbling to have met so many school survivors and to have heard their stories first-hand. I am very appreciative of my colleague Andrew Martindale and of fellow members of the BC Technical Working Group for their generous information sharing. I am grateful to GeoScan director Will Meredith for encouraging me to prepare this submission and to my field and office team at GeoScan: Peter Takacs, Joe Durrant, Jack Goozee, Jon Jacobson, Adam Czecholinski, Yvonne Houlihan and Anna Turner-Collinge—the important work we are doing would not be possible without each of you. Finally, the comments of two anonymous reviewers greatly improved this manuscript, although any errors and omissions remain my own.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

This submission was written based on experience gained while working for the above company on a number of Indian residential school projects in Western Canada. There is no known conflict of interest, and ethical boundaries are maintained by non-disclosure of specific First Nations community and school names and locations.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1 The term residential schools is sometimes used in a relatively narrow sense that refers to a widespread system of boarding schools that were typically started operated by churches and eventually mandated and funded by the Canadian government. In a broader sense, many residential schools were run by churches without government funding or direct supervision. In addition, a large number of children were required to attend non-residential day schools that may have had associated hostels or dormitories for housing students and thus may not have been considered residential schools per se. Many hospital sites also come under the purview of IRS investigations. While First Nations children were the primary focus of residential schools, many Inuit and Métis children also attended. Therefore, there are definition and scope problems associated with the search for unmarked student graves that require care, sensitivity and attention. In this manuscript, the terms Indian residential school(s), IRS, residential schools and sometimes just schools will be used as a shorthand notation to include all of the above facilities that held Indian, Métis and Inuit children from the early 19th Century until 1997.

- 2 However, ‘GPR’ may be approaching the status of household word in Canada due to news-media attention.

- 3 Canadian Indian residential schools were in many ways explicitly modelled on similar schools that were located throughout the United State (and vice versa); these also are known to have been extremely neglectful and abusive (Adams, 1995), although schools in the United States have not received the same level of national-level attention as they have in Canada. Despite the similarities, this manuscript will focus exclusively on Canadian schools.

- 4 In this manuscript, I will use the term ‘Indigenous’ to reference government-defined ‘status’ and ‘non-status’ as well as Métis and Inuit peoples in Canada. It is important to emphasize that members of all types of Indigenous communities were sent to Indian residential schools, not just more narrowly defined (per the 1876 Indian Act) ‘Indians’.

- 5 It should be noted that the Indian Act and amendments had numerous other intentions and effects.

- 6 Full membership level of the UK-based Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, awarded for highest-level demonstrated geophysics competence (CIfA Geophysics Group, 2016)

- 7 It is worth mentioning that technical proposals for IRS searches are always reviewed by First Nations project managers. In the author's experience, the technical approach has not been challenged, but communities always have important input on timing, location of searches, ceremonial protocol and on the mode and audience of reporting.

- 8 In the author's experience, these stacking methods have matured tremendously in the past 3–5 years and make investing in newer GPR equipment well worth considering. In the particular case of dual-frequency GPR, the stacking algorithms built into the electronics have resulted in surprisingly deep and clear results from the high-frequency (e.g., 800 MHz) antenna set.

- 9 The author has developed GIS predictive models based on overlay analysis of factors such as distance from a school, viewshed/sight lines from the school, suitable slope and suitable soi, all registered to a base of archival air photos showing the school in question as it existed at various times in the past.