The Dynamics of Satisfaction with Working Hours in Australia: The Usefulness of Panel Data in Evaluating the Case for Policy Intervention

Abstract

The case for policy intervention in social or economic problems should be based on incidence, severity and persistence of the problem. In this article, we show the usefulness of panel data in this regard by comparing preferred working hours to actual working hours, and examining the degree of mismatch between the two. Some individuals report working more hours than they would prefer, whereas others prefer working less. We examine the prevalence, severity and persistence of both types of problems. The case for policy intervention is weak as most working hour mismatch problems are resolved in a short time period.

1. Introduction

The pressure for policy intervention to improve people's lives is strong. The media, social pressure groups, opposition political parties and many others regularly identify dissatisfied groups of people or societal problems and appeal for some type of public policy intervention. These types of calls for intervention are then evaluated in some type of cost-benefit framework. Cost-benefit analysis may only be applied very loosely, but any intervention clearly has costs and benefits, and these are generally enumerated, if not costed, by those who argue for or against intervention.

In this article, we demonstrate the usefulness of panel data in making a case for public policy intervention. We begin from a simple premise: any case for intervention must be made on the basis of three dimensions: incidence of the problem, severity of the problem and persistence of the problem. Problems that are widespread, severe and persistent provide a compelling case for policy intervention, for example, malaria eradication and access to clean drinking water in developing countries today, or smallpox eradication in the past. There are tradeoffs across these three dimensions, and not all problems need to score ‘high’ in all three dimensions. We can make a compelling case for intervention for problems with low incidence, but which are severe and persistent, for example, severe disability and the policy intervention of the National Disability Insurance Scheme in Australia.

Cross-sectional data, such as the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Housing and Expenditure Survey, can provide information about incidence and severity of problems. But because different individuals are interviewed in subsequent waves of the data, it is not possible to learn about persistence from such cross-sectional surveys. One solution is to ask individuals retrospective questions about their situation in the past, but such responses tend to be unreliable as a large literature in statistics has documented. (For a recent example, see de Nicola & Giné 2011, and the references cited therein.) Panel data not only can provide information about incidence and severity but also information about persistence as the same individuals are followed over time and current responses for each time period can be tracked over time to provide information about movement and dynamics.

In this article, we show how panel data can be used to get a feel for the likely benefits of policy intervention. Solutions to problems that have only a small incidence, which are not severe and which are not persistent, will bring only small benefit. We also have as a background premise that policy intervention always comes with costs. There are administrative costs for the government in running programs and compliance costs for individuals and businesses. Although one may debate the magnitude of the problem, raising taxes has at least some negative consequences on economic activity. Policy intervention also often has unintended consequences that are hard to foresee even in the most well-designed programs. This worldview provides an a priori argument against any policy intervention for which the likely benefits are small.

The Prime Minister Julia Gillard last week outlined her government's economic priorities for 2011 to a CEDA lunch in Melbourne. In her speech, she noted, in the context of skills shortages, her concern over: ‘the large number of working-age Australians, possibly as many as two million, who stand outside the full-time labour force, above and beyond those registered as unemployed. Around 800,000 are in part-time jobs but want to work more. Another 800,000 are outside the labour market, including discouraged job seekers.

In this article, we focus specifically on the group who are working but say they want to work more. In fairness, we also consider those who are working but say they want to work less.

Labour force surveys typically find a substantial fraction of workers who express dissatisfaction with their current working hours. In this article, we examine the extent of this dissatisfaction and the dynamics of individual reports of dissatisfaction with working hours. We examine both those workers who report working more hours than desired (‘overemployed’) and those who report working less hours than desired (‘underemployed’). If a correct match between actual and desired hours is related to worker well-being, then both types of mismatch between preferred and actual hours (‘hours mismatch’) should be considered.

Working hours are only one dimension of a job. Jobs are composed of a variety of characteristics, including wage, intellectual stimulation, physical exertion, danger, satisfaction with colleagues and supervisors, and other important features. It may be that individuals who report dissatisfaction with working hours are nonetheless globally satisfied with their job because of other compensating characteristics, as seen in Altonji and Paxson (1988). Wooden et al. (2009) and Wilkins (2004) examine the relationship between hours mismatch and overall job satisfaction and find that they are correlated. A potential consequence of hour mismatch may be higher job separation rates where individuals seek a better match outside their existing workplace, as observed in the United States (Altonji & Paxson 1992) and the United Kingdom (Blundell et al. 2005).

In a healthy labour market that is creating new jobs, dissatisfied individuals should have opportunities to move to jobs that suit them better. Persistent mismatch between preferred and actual hours, therefore, could be interpreted as a failure in the labour market, or could be interpreted as individuals who are actively choosing to remain in jobs with which they are dissatisfied with their hours but for which they feel compensated by other characteristics.

If hours mismatch is a short-lived phenomena, and individuals are able to adjust their hours or change jobs to find a better match, then it should not be of major concern to policy-makers. The policy prescription would be to encourage smooth functioning of the labour market. 2 If, on the other hand, hours mismatch combined with overall job dissatisfaction is a persistent phenomenon, then there may be a case for policy intervention to help workers improve the match between their actual working hours and their desired working hours.

These questions provide the motivation for our study. We aim to carefully and clearly examine the prevalence, severity and persistence of working hour mismatch in Australia. We show that dissatisfaction with working hours is by and large a transitory state. Exploiting the dynamic panel nature of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, we show that the majority of workers who feel that they are working too little express satisfaction with their working hours in future waves. Thus, dissatisfaction seems to be a temporary state through which people pass on the way to finding the job that suits them. We also show that workers' dissatisfaction with working hours due to working too many hours is quite different and is much more persistent. Interestingly, men and women exhibit very similar trends in hour mismatch statistics after accounting for full-time and part-time labour force status.

2. Measuring and Analysing Working Hour Mismatch in Australia

Past research into the hour preferences of Australians has seen a variety of data sources examined and some differences between seemingly comparable measures reported. There has been a limited focus on the transitions between states of underemployment, overemployment and satisfaction with working hours. We briefly discuss issues of survey design and how they impact on measures of the prevalence of underemployment and overemployment. We then review the Australian literature.

In this article, we restrict our analysis to those who are working. Unemployment can be viewed as a mismatch between desired (positive) and actual (zero) working hours; however, the two groups are typically separated in research. The fact that the underemployed have a job justifies a separate analysis of their outcomes as that signals that paid work exists given their skills and reservation wage. (For the unemployed, we cannot be sure if there is any job that exists at the individual's reservation wage and given the individual's productivity). Further, Wooden et al. (2009) show that the overemployed have lower life satisfaction outcomes than the underemployed, whereas the unemployed are much less satisfied than any group of workers.

2.1 Survey Questionnaire Phrasing

Appendix 1 Table A1 summarises Australian hour mismatch statistics derived from data sources not used in this article. Underemployment rates across the data sources range from 7.1 per cent to 29 per cent, and overemployment ranges from 10 per cent to 50 per cent. These bounds are not explained by standard measurement error and sampling variation; rather, they illustrate the sensitivity of survey responses to the phrasing of questions and sample exclusions. In general, questions that ask respondents to state their preferred hours when taking into account the income effect of their decision get higher rates of underemployment and lower rates of overemployment than questions that do not ask for consideration of the income effects. This sensitivity provides an important caveat to analysis of hour mismatch. In particular, attention should be paid to question wording when conducting any cross-study or cross-country comparison.

Lang and Khan (2001) discuss the sensitivity of responses to the wording of survey questions on work hour preferences in the 1986 Canadian Survey of Work Reduction to the method of attaching financial consequences with hour decisions. Likewise, Golden and Gebreselassie (2007) discuss the issue of survey wording after summarising American data sources to find a wide range of overemployment rates.

2.2 Review of Australian Literature

We review the literature through the three dimensions discussed above—prevalence/incidence, severity and persistence—noting that the work on persistence has been fairly limited. We also briefly discuss work that has been done on the patterns of underemployment and overemployment over the business cycle.

Prevalence

Studies based upon the HILDA data consistently find that more Australians prefer fewer hours rather than more hours. 3 When examining other data sources, the prevalence of working hour mismatches seen in the HILDA data is largely supported. The exception to this is the Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA), which reported underemployment as more prevalent than overemployment. 4 However, the AuSSA survey uses phrasing of the hour mismatch question that when used in other countries often reveals a larger underemployed population. 5

The demographic composition of the underemployed and overemployed is an area that has been well examined. Prime working-age Australians with working hour preference mismatches are more likely to be overemployed and less likely to be underemployed than people aged under 25. Likewise, university education is associated with higher rates of overemployment and lower rates of underemployment. These trends are found in both the HILDA dataset (Tseng & Wooden 2005; Wilkins 2006) and ABS data (ABS 2010, 2012). Tseng and Wooden (2005) also show that migrants from non-English-speaking backgrounds are more likely to desire more hours than their current arrangement and less likely to desire fewer hours. Partnered workers are more likely to be overemployed (ABS 2011), and the HILDA data show that people are likely to desire more (less) hours than their current hours if their partner also would prefer to work more (less) hours (Tseng & Wooden 2005). Reynolds and Aletraris (2007) construct a work–family conflict variable and associate it with an increased desire for fewer hours for both men and women, with the effects stronger for women if they have a young child. They also find that household income significantly impacts male hour mismatches in both directions, but not females in a couple.

Notable job characteristics that are correlated with hour mismatch include employment type and industry and occupation. Casual workers and the self-employed are more likely to be underemployed, with strong industry and occupation effects (Wilkins 2006; ABS 2010; Fear et al. 2010). It is uncertain what the causal factors for hour mismatch are as industry and occupation may influence the probability of being a salaried worker and other work conditions.

Due to the subjectivity of hour preference survey questions, causal relationships between satisfaction-based variables can be difficult to identify. For example, one may dislike his or her work environment and therefore desire less hours, making it difficult to ascertain which factor leads to lower job satisfaction. Tseng and Wooden (2005) show that people who enjoy having a job are unsurprisingly less likely to want fewer hours and more likely to want more hours. Similarly, Reynolds and Aletraris (2007) associate stress with a desire for fewer hours for both men and women in couples.

Labour demand factors are not present in the HILDA survey data and may be useful for hour mismatch analysis. Baum and Mitchell (2008) add some regional labour market information to HILDA Wave 1 in their analysis of 15- to 24-year-old Australians and find that higher proportions of low income jobs in a region increase the likelihood that the region's youth are underemployed. An area that cannot be explored using the HILDA dataset is the relationship between hour mismatch and employer/firm characteristics. Doiron (2003) used data from the 1995 Australian Workplace Industrial Relations Survey to match firm and worker data, finding that contracting firms do not hoard labour as they are less likely to have underemployed workers than expanding firms. Furthermore, non-contracting firms show a negative job tenure/probability of underemployment relationship for their workers. This suggests that changes in the characteristics of individual firms may influence hour mismatches of workers.

Severity

Similar to prevalence statistics, HILDA data consistently exhibit an average preference for less hours of work for both males and females. Appendix 1 Table A1 shows that where information on severity is produced from other Australian surveys, there is an average preference for less hours of work across the sample.

ABS categorises the most severely overemployed as workers who work 60 or more hours per week. Similarly, the most severely underemployed are workers of low hours, with the underemployed male workers wanting more additional hours than the underemployed females (ABS 2010, 2011). These trends are supported by Fear et al. (2010).

Tseng and Wooden (2005) measure the extent of both underemployment and overemployment in couple households by performing a conditional ordinary least squares regression on the hour mismatch for both groups. Of the overemployed, the average mismatch is greater for the self-employed and when the partner is overemployed, and the average mismatch is lower with a recent unemployment spell and if their partner is employed part-time. There are also significant age effects with prime age workers the most susceptible to overemployment. Of the underemployed, the mismatch is greater for casual, self-employed and non-English-speaking background workers, and the mismatch is lower for people with an overemployed partner.

Persistence

The longitudinal Negotiating the Life Course (NLC) survey (van Wanrooy 2004, 2005; McDonald et al. 2009) supports our results below by showing that overemployment is a more persistent state in the NLC data than underemployment.

Reynolds and Aletraris (2006) use the first two waves of HILDA data to show that a desire for more hours is more likely to be resolved than a desire for less hours between surveys. They also show that in creating and resolving hour mismatches, both preferred and actual hours adjust in most cases, with preferred hours often moving the most for resolving or desiring fewer hours. This suggests that people may acclimatise to their working situations. They find that men and women who change both their actual or preferred hours are more likely to resolve a mismatch than people who do not, and that men are more likely to resolve a desire for more hours than fewer hours.

Reynolds and Aletraris (2006) also test the effect of a range of job-specific, personal and family characteristics on creating and resolving hour mismatches. The strongest relationship found is an increased likelihood of resolving mismatches if people change their job. For females, lower household hours of work are associated with a lower chance of resolution, with younger and older workers more likely than the middle-aged to resolve a mismatch. For males, the presence of another earner in their household and feeling secure in their job improve the odds of resolving mismatches, and like females higher hours of work are associated with a decline in the odds. In creating hour mismatches, changes in preferred hours are positively associated with hour mismatches, whereas changes in actual hours are negatively related. People on higher incomes are less likely to develop a preference for more hours, and male professionals and managers are more likely to develop overemployment, likewise university-educated females. Women who have a teenage youngest child are more likely to create an unmet desire for more hours, while women who believe working harms their relationship with their child are more likely to develop overemployment.

In an article that is strongly related to ours, Wooden and Drago (2007) analyse the first five waves of the HILDA data asking the same set of questions that we do. They begin by looking at working hour preferences by sex and usual working hours. The patterns that they report in the first five waves are, unsurprisingly, very similar to what we report. They also look at the magnitude of hours mismatches by sex, and again our numbers for the early waves are similar to theirs. They examine persistence across one wave and multiple waves. Taking matched pairs of people employed at both time periods, they examine the reported hour mismatches at time t compared with those at time t + l for people with mismatches at time t, allowing l to take values from one through four. In this article, we primarily look at persistence over one time period, although we briefly discuss longer time horizons as well. Wooden and Drago (2007) do not examine the role of job changes nor do they look at what changes when hour mismatches are resolved, as we do below. However, in addition to examining longer time lags, they undertake some analyses that we do not. They look at annual hours versus weekly hours and the relationship between paid leave entitlements and whether or not they are taken up. They find no evidence that those working long hours are less likely to take up annual leave. They also provide some international comparisons.

When restricting the analysis sample to Australians with high working hours, Drago et al. (2009) reveals persistent high-hour overemployment for university-educated managers and professionals, fathers with a partner who works, and people with high debt to income ratios. Over time, fathers appear to accept their long hours by changing their preferences to match their long working hour situation.

Working Hour Mismatch and the Business Cycle

Analysis of the macro-dynamics of working hour mismatch tends to be limited to underemployment rather than all hour mismatches. The ABS (2010) and Campbell (2008) provide descriptions of the underemployment measures used by the ABS and show that underemployment varies less over the business cycle than unemployment. Rather, there appears to be an increase in the aggregate rate of underemployment at the beginning of an economic downturn with the new level maintained longer as the business cycle returns back to growth. Mitchell and Carlson (2000) use the ABS data to construct indexes of labour force underutilisation using the difference between reported and preferred working hours, and show that these indexes may evolve differently from the unemployment rate. The percentage of part-time work may increase at some points in the business cycle, and the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (2011) discussed the relationship between part-time work and mismatch between preferred and actual working hours.

We extend the above literature by looking at all three dimensions of mismatch between actual and preferred working hours across an 11-year span. In the next section, we describe our data before considering the three dimensions in detail.

3. Data and Analysis Sample

We use the first 11 waves (2001–2011) of the HILDA survey. HILDA is a longitudinal survey containing rich information on individual's work patterns and preferences along with other important personal and family characteristics. As discussed above, the use of panel data allows us to describe persistence of working hour mismatches by tracking individuals over time. Wave 1 had a household response rate of 66 per cent and an individual response rate of 92 per cent, resulting in 7,682 households and 13,969 individual respondents aged over 15 years. For more information on the HILDA survey, including the sample sizes and response rates for all waves, see Watson and Wooden (2002) and Summerfield et al. (2011).

3.1 Measuring Prevalence

- #jbhrcpr: If you could choose the number of hours you work each week, and taking into account how that would affect your income, would you prefer to work:

- fewer hours than you do now

- about the same hours as you do now or

- more hours than you do now?

3.2 Measuring Severity

- #jbprhr: In total, how many hours a week, on average, would you choose to work? Again, take into account how that would affect your income.

When respondents to #jbhrcpr report that they are content with their current working hour arrangements, we set their preferred hours to their usual hours worked or average hours worked if usual hours are unknown. We also treat people who work but ‘don't know’ whether they are satisfied with their hours in the same manner. When there are inconsistencies or missing values in the responses for labour force status, preference to work more or less hours, usual hours and/or preferred hours, we set the working preference variables to missing.

Once preferred hours are derived for our sample, we calculate the difference between that value and usual working hours to construct a severity measure for working time preference mismatch. In any cases where either usual or preferred hours are missing, we set the severity measure to missing.

3.3 Measuring Persistence

The description of persistence of working hour preference mismatches is constructed from the same variables used in identifying the prevalence of mismatches. We analyse responses between two consecutive waves to the hour preference survey question and construct transition variables accordingly. Therefore, a person who is employed in all 11 waves of HILDA will have 10 observations for our transition variables. Note that although we refer to these variables as ‘transitions’, they are point in time survey responses, approximately one year apart for each person. Multiple midyear changes of working hour preference mismatches are not observed, but we can capture job changes between responses for analysis.

To further our analysis of transitions in working hour preference mismatches, we construct indicators for changes in preferred hours and usual working hour changes between waves, where indictors are only constructed for people who have non-missing values for these variables in both waves, as described in the severity section above.

3.4 Measuring Job/Employer Changes

We use information across waves to create a measure of whether or not people have changed job. For those who report only having had one job in the past, we use the response to #pjsemp, which asks whether the individual has changed employers. For those who report having multiple jobs, we use the response to #pjmsemp, which asks whether the individual has changed employers for the main job. We verify employment status in the previous period using the answer from the previous wave and only record job changes for those who were employed at both waves since this is what we are comparing in our persistence measure. Further, for a small number of individuals, they report not changing employers, but they report changing jobs (they respond to the questions about the reason for job change, #pjorea). We code these people (who are very few in number) as having changed jobs even though they appear to not have changed employer.

3.5 Sample Exclusions

There are 12,599 men who appear in HILDA during at least one of the first 11 waves. Of these, 2,861 never answer the questions relating to working time preference mismatches, primarily because they are not in the labour force at the point in time when they respond to the survey. These individuals are dropped, leaving 9,738 men across the 11 data waves who remain in our analysis sample. Each individual who has answered the hours preference question for at least one wave is kept for all waves. Thus, in our analysis sample, some individuals have answered the hours preference question once, whereas some have answered the question in the 11 consecutive waves and there are many other possibilities in between these two extremes. In total, there are 49,414 observations across the 11 waves on these 9,738 unique individuals. Of the 49,352 valid responses, 40,911 of them relate to full-time employed men and 8,503 relate to part-time employed men.

There are 13,431 women who appear in HILDA during at least one of the first 11 waves. Of these, 4,208 never answer the questions relating to working time preference mismatches. These individuals are dropped, leaving 9,223 women across the 11 data waves who remain in our analysis sample. Each of these individuals has answered the hours preference question at least once. In total, there are 44,715 observations across the 11 waves on these 9,223 unique individuals. The sample of women is much more evenly split between full- and part-time, with 22,750 observations on full-time employed women and 21,965 on part-time employed women.

We use all of these individuals and their responses, and we make no other sample exclusions in our analysis of the incidence of working hour mismatch. When we consider severity, we drop observations with missing data for either actual working hours or preferred hours. Since we are particularly interested in transitions, we consider that non-response in a wave is a possible outcome, so individuals who respond at time t and are missing at time t + 1 are included in the sample we use for analysing transitions. Tables 1-3 show total and wave-specific sample sizes by gender and by full- and part-time.

| Year (wave) | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All employed (number of observations) | Prefer to work less (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | All employed (number of observations) | Prefer to work less (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| 2001 (1) | 4,546 | 29.6 | 15.8 | 3,975 | 26.7 | 17.0 |

| 2002 (2) | 4,325 | 30.5 | 16.0 | 3,762 | 24.3 | 17.9 |

| 2003 (3) | 4,246 | 30.1 | 15.0 | 3,743 | 25.9 | 17.6 |

| 2004 (4) | 4,155 | 30.9 | 14.0 | 3,665 | 26.4 | 16.1 |

| 2005 (5) | 4,304 | 29.4 | 12.8 | 3,940 | 26.8 | 16.7 |

| 2006 (6) | 4,353 | 28.8 | 13.7 | 4,002 | 27.3 | 15.1 |

| 2007 (7) | 4,307 | 28.9 | 12.0 | 4,034 | 27.0 | 14.6 |

| 2008 (8) | 4,337 | 27.8 | 12.6 | 4,032 | 25.8 | 14.3 |

| 2009 (9) | 4,484 | 27.0 | 13.6 | 4,065 | 23.6 | 15.6 |

| 2010 (10) | 4,508 | 26.0 | 13.2 | 4,140 | 25.7 | 16.2 |

| 2011 (11) | 5,849 | 24.6 | 15.8 | 5,356 | 24.2 | 17.1 |

| All | 49,414 | 28.4 | 14.0 | 44,715 | 25.8 | 16.2 |

- Note: Differences between percentage who prefer to work less and percentage who prefer to work more are statistically significant for all waves and total.

| Year (wave) | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-time employed (number of observations) | Prefer to work less (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Full-time employed (number of observations) | Prefer to work less (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| 2001 (1) | 3,794 | 34.2 | 10.3 | 2,001 | 42.1 | 5.5 |

| 2002 (2) | 3,576 | 35.7 | 10.2 | 1,874 | 39.8 | 5.2 |

| 2003 (3) | 3,523 | 35.0 | 8.8 | 1,873 | 42.1 | 3.2 |

| 2004 (4) | 3,441 | 36.3 | 8.7 | 1,835 | 43.0 | 3.8 |

| 2005 (5) | 3,587 | 34.1 | 8.1 | 1,969 | 43.4 | 4.6 |

| 2006 (6) | 3,579 | 33.8 | 7.9 | 2,055 | 42.6 | 4.7 |

| 2007 (7) | 3,564 | 33.5 | 6.7 | 2,104 | 41.9 | 3.0 |

| 2008 (8) | 3,635 | 31.7 | 8.2 | 2,092 | 39.9 | 3.8 |

| 2009 (9) | 3,686 | 31.5 | 8.3 | 2,106 | 38.2 | 4.2 |

| 2010 (10) | 3,730 | 30.2 | 8.4 | 2,127 | 40.3 | 5.1 |

| 2011 (11) | 4,796 | 29.3 | 9.7 | 2,714 | 39.5 | 4.2 |

| All | 40,911 | 33.1 | 8.6 | 22,750 | 41.1 | 4.3 |

- Notes: Differences between percentage who prefer to work less and percentage who prefer to work more are statistically significant for all waves and total. Full-time employed are defined as working 35 hours or more per week.

| Year (wave) | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part-time employed (number of observations) | Prefer to work less (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Part-time employed (number of observations) | Prefer to work less (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| 2001 (1) | 752 | 6.5 | 43.7 | 1,975 | 9.5 | 29.8 |

| 2002 (2) | 749 | 4.8 | 44.8 | 1,888 | 7.8 | 31.4 |

| 2003 (3) | 723 | 6.4 | 45.1 | 1,870 | 9.1 | 32.7 |

| 2004 (4) | 714 | 5.5 | 39.2 | 1,830 | 9.0 | 28.9 |

| 2005 (5) | 717 | 4.5 | 37.2 | 1,971 | 9.6 | 29.2 |

| 2006 (6) | 774 | 5.7 | 40.3 | 1,947 | 9.7 | 27.0 |

| 2007 (7) | 743 | 5.8 | 38.3 | 1,930 | 9.8 | 28.0 |

| 2008 (8) | 702 | 6.2 | 36.6 | 1,940 | 9.2 | 26.6 |

| 2009 (9) | 798 | 5.7 | 38.7 | 1,959 | 7.3 | 28.4 |

| 2010 (10) | 778 | 5.8 | 36.3 | 2,013 | 9.1 | 28.9 |

| 2011 (11) | 1,053 | 5.0 | 40.7 | 2,642 | 8.0 | 30.7 |

| All | 8,053 | 5.6 | 40.0 | 21,965 | 8.9 | 29.2 |

- Note: Differences between percentage who prefer to work less and percentage who prefer to work more are statistically significant for all waves and total.

4. Patterns of Mismatch between Actual and Desired Work Hours

This section will provide a detailed descriptive analysis of the data. We first look at the prevalence of mismatches between desired and actual working hours. We consider the ‘headcount’ measure based upon the HILDA question #jbhrcpr, which is described in Section 3.1. We then look at the gap between desired hours and actual hours worked to get an idea of severity of the problem. Our approach is akin to the one used in poverty measurement where in addition to simply counting the number of poor we also look at the distance between income and the poverty line. Here, we look at the distance between desired and actual hours worked.

We also look at persistence for the reasons discussed in the introduction above. If hours mismatch is a transitory state, then it may not be an appropriate target for policy. If hours mismatch is persistent, then an argument for some type of policy intervention could be made provided it can be shown that hours mismatch is a result of some type of market failure.

4.1 Prevalence

Tables 1-3 show the rates of prevalence of working hours mismatch for men and women. Table 1 shows values for all workers with males in columns 2 through 4 and females in columns 5 through 7. The table shows wave-by-wave percentages of people who indicate that they would prefer to work more hours and those who indicate that they would prefer to work less hours. In the last row, responses are totalled across all waves. Tables 2 and 3 show the same information, but split by employment status. Full-time workers are shown in Table 2 and part-time workers in Table 3. We present weighted data throughout the article. We use the svy commands in STATA (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), and all standard errors and hypotheses tests make use of the jackknife replicate weights.

- ‘Over-work’ is much more prevalent than ‘under-work’.

- Full-time workers are overwhelmingly more likely to desire less hours.

- Part-time workers are more likely to prefer more hours.

- Across all workers, nearly twice as many individuals report a preference to work less hours than report a preference to work more hours.

- Average response rates to questions about wanting to work more or less are relatively stable across the 2001–2010 sample period.

- With some imagination, one can discern an effect of the strong economic conditions in Australia in 2004–2008 and the global financial crisis in 2009.

For part-time employed males, the percentage of those who preferred to work more went down from 2004–2008 as employment demand rose and seems to have gone back up after 2009, perhaps in response to the global financial crisis. The numbers of those who preferred to work also appear to peak in 2004–2008 and drop after 2009.

4.2 Severity

Next, we examine the question of how large the difference is between individuals’ reported and desired hours. In the previous section, we show that many more people report a desire to work less hours than more hours. However, it may be the case that the people who want to work less hours only want to work two or three less hours a week, whereas those who want more hours might want to work 20 or more additional hours a week. In this case, the prevalence measure we show above may mask an important dimension of hour mismatch.

In this section, we create a measure of hours mismatch ‘severity’ based upon the difference between stated desired working hours and actual working hours (measured as actual or usual hours worked per week). One hundred twenty-one men and 102 women have missing information on either actual or preferred hours and are dropped for this section. Of those remaining, 14,215 men have desired hours less than actual hours (providing a negative value for our severity measure), whereas 6,764 men have desired hours greater than actual hours and thus a positive value for our severity measure. There were 28,314 men satisfied with their hours. For women, 11,306 have desired hours less than actual hours, and 7,318 have desired hours greater than actual hours. There were 25,989 who report being content with their current hours.

Table 4 presents the results for all male workers across all 11 waves of the survey. Table 5 presents the results for all working women. In the third column, we present the total number of hours per week by which those who prefer to work less would need to change their hours in order to have actual hours match desired hours. In the fifth column, we present the same thing for those who wish to work more. The last column provides the change in the number of hours per week per male worker with a mismatch that would need to happen for actual and desired hour to be aligned with one another.

| Year (wave) | Prefer to work less | Prefer to work more | Any mismatch | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of workers | Average hours | Number of workers | Average hours | Number of workers | Average hours | |

| 2001 (1) | 1,372 | −14.3 | 691 | 11.6 | 2,063 | −5.3 |

| 2002 (2) | 1,352 | −14.6 | 652 | 12.0 | 2,004 | −5.5 |

| 2003 (3) | 1,326 | −14.3 | 579 | 11.7 | 1,905 | −5.7 |

| 2004 (4) | 1,282 | −14.6 | 551 | 12.2 | 1,833 | −6.3 |

| 2005 (5) | 1,274 | −14.4 | 564 | 12.2 | 1,838 | −6.3 |

| 2006 (6) | 1,285 | −14.4 | 569 | 12.7 | 1,854 | −5.7 |

| 2007 (7) | 1,233 | −14.3 | 514 | 11.9 | 1,747 | −6.6 |

| 2008 (8) | 1,204 | −14.2 | 530 | 11.5 | 1.734 | −6.2 |

| 2009 (9) | 1,226 | −14.6 | 629 | 12.1 | 1,855 | −5.7 |

| 2010 (10) | 1,153 | −13.8 | 621 | 11.5 | 1,774 | −5.3 |

| 2011 (11) | 1,508 | −13.7 | 864 | 12.3 | 2,372 | −3.5 |

| All | 14,215 | −14.3 | 6,764 | 12.0 | 20,979 | −5.6 |

- Note: Differences between average hours for those who prefer to work less and those who prefer to work more are statistically significant for all waves and total.

| Year (wave) | Prefer to work less | Prefer to work more | Any mismatch | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of workers | Average hours | Number of workers | Average hours | Number of workers | Average hours | |

| 2001 (1) | 1,059 | −13.3 | 682 | 11.6 | 1,741 | −3.6 |

| 2002 (2) | 925 | −13.1 | 664 | 11.3 | 1,589 | −2.7 |

| 2003 (3) | 941 | −13.0 | 648 | 11.6 | 1,589 | −3.0 |

| 2004 (4) | 946 | −12.8 | 597 | 11.3 | 1,543 | −3.7 |

| 2005 (5) | 1,031 | −13.3 | 667 | 11.2 | 1,698 | −4.0 |

| 2006 (6) | 1,042 | −12.8 | 611 | 10.4 | 1,653 | −4.5 |

| 2007 (7) | 1,075 | −13.4 | 619 | 10.7 | 1,694 | −4.9 |

| 2008 (8) | 1,013 | −13.0 | 585 | 11.0 | 1.598 | −4.4 |

| 2009 (9) | 971 | −13.6 | 636 | 10.5 | 1,607 | −4.0 |

| 2010 (10) | 1,015 | −13.1 | 690 | 10.7 | 1,705 | −3.9 |

| 2011 (11) | 1,288 | −12.9 | 919 | 11.3 | 2,207 | −2.9 |

| All | 11,306 | −13.1 | 7,318 | 11.0 | 18,624 | −3.8 |

- Note: Differences between average hours for those who prefer to work less and those who prefer to work more are statistically significant for all waves and total.

If all male workers could magically be matched to their preferred hours, this would represent a 12.9 per cent decrease in labour supply for workers who currently have a mismatch. This would represent a 5.7 per cent decrease in labour supply across all workers. The analogous percentages for women are very similar at 11.4 per cent and 5.6 per cent.

These figures are staggering, particularly in light of the quote from former Prime Minister Gillard above. A government intervention to match workers to preferred hours, often presented in a discussion of possible policies to increase labour supply, would in fact have the opposite effect and a large one at that.

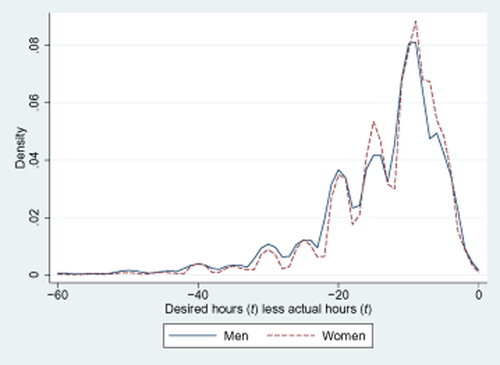

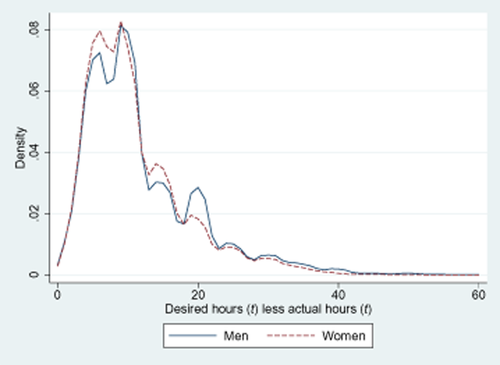

Figures 1 and 2 present non-parametric density estimates for the distribution of the difference between desired and actual hours separately for those who wish to work less and those who wish to work more. 6 What is striking about these two figures is the similarity between the distributions for men and women. This mimics our conclusion from Section 4.1 where we saw little difference between men and women once we split the sample into full- and part-time workers.

Hours Mismatch for Those Who Report Preferring to Work Less Hours

Hours Mismatch for Those Who Report Preferring to Work More Hours

The conclusion from the prevalence analysis is supported by the evidence from the severity analysis. The magnitude of overwork is larger than underwork in Australia. Aligning desired and actual hours across all workers would result in a decrease in hours worked of between 5 and 6 per cent across all workers.

4.3 Persistence

In the previous sections, we have considered the prevalence and severity of the mismatch between desired and actual working hours. To enhance our understanding of this mismatch, we also need to consider what happens to those people who experience a mismatch between actual and desired hours. Does the mismatch persist over time or is it transitory? We can use the panel nature of the HILDA data to look at this dimension of the mismatch.

The first question we ask is, ‘what happens in time t + 1 to people who experience an hours mismatch at time t?’ Tables 6 and 7 provide the answer to this question for men and women, respectively. In each table, the top panel pools across all workers and all waves, whereas the second panel pools across full-time workers in all waves, and the third panel across part-time workers in all waves. If we do the analysis wave by wave, the patterns are similar to the ones that we present here.

| (A): Transitions of All Male Workers—All Waves | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | ||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 53.5 | 15.5 | 6.9 |

| Current hours okay | 29.9 | 62.4 | 36.4 |

| Prefer to work more | 3.1 | 7.3 | 35.0 |

| Other (present in survey) | 4.0 | 5.2 | 8.7 |

| Missing | 9.5 | 9.6 | 13.0 |

| Number of observations | 12,722 | 24,928 | 5,915 |

| (B): Transitions of Full-Time Male Workers—All Waves | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | ||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 54.5 | 16.9 | 7.7 |

| Current hours okay | 29.6 | 63.7 | 39.6 |

| Prefer to work more | 2.9 | 6.3 | 35.5 |

| Other (present in survey) | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.6 |

| Missing | 9.6 | 10.0 | 13.6 |

| Number of observations | 12,310 | 20,862 | 2,943 |

| (C): Transitions of Male Part-Time Workers—All Waves | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | ||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 24.9 | 8.2 | 6.0 |

| Current hours okay | 38.0 | 55.8 | 34.0 |

| Prefer to work more | 10.1 | 12.5 | 34.5 |

| Other (present in survey) | 19.3 | 15.6 | 14.0 |

| Missing | 7.8 | 7.9 | 12.4 |

| Number of observations | 412 | 4,066 | 2,972 |

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are part-time at t − 1.

| (A): Transitions of All Female Workers—All Waves | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | ||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 49.5 | 14.8 | 7.0 |

| Current hours okay | 30.9 | 59.4 | 36.4 |

| Prefer to work more | 3.9 | 8.7 | 33.8 |

| Other (present in survey) | 7.2 | 8.2 | 11.8 |

| Missing | 8.5 | 9.0 | 11.1 |

| Number of observations | 10,036 | 22,909 | 6,414 |

| (B): Transitions of Full-Time Female Workers—All Waves | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | ||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 53.4 | 20.1 | 6.6 |

| Current hours okay | 28.6 | 59.6 | 41.8 |

| Prefer to work more | 3.3 | 5.1 | 27.3 |

| Other (present in survey) | 5.9 | 4.7 | 7.7 |

| Missing | 8.8 | 10.6 | 16.6 |

| Number of observations | 8,322 | 10,898 | 816 |

| (C): Transitions of Female Part-Time Workers—All Waves | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | ||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 29.7 | 9.6 | 7.0 |

| Current hours okay | 42.5 | 59.3 | 35.5 |

| Prefer to work more | 6.9 | 12.1 | 34.8 |

| Other (present in survey) | 13.4 | 11.5 | 12.5 |

| Missing | 7.5 | 7.4 | 10.2 |

| Number of observations | 1,714 | 12,011 | 5,598 |

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are part-time at t − 1.

The second column of the table looks at all individuals who report a desire to work less at a particular wave (year). We then look at the same individual one wave (year) later and classify them according to one of five possibilities: (i) they would still prefer to work less hours; (ii) they are now satisfied with their hours; (iii) they would now prefer to work more hours; (iv) they are still present in the survey but are no longer working (the individual could be unemployed or not in the labour force); and (v) they are missing from the survey. This final category is included for completeness and allows us to see whether there is different attrition from the survey based upon satisfaction with working hours. Columns 3 and 4 look at those who were satisfied with their hours in a previous wave and those who wished to work more in a previous wave, respectively, and again classify them by their status in the following wave.

- There is a large degree of movement between the categories.

- Dissatisfaction relating to working too many hours is much more persistent than dissatisfaction with working too few hours.

For both full-time men and full-time women, about half of those who wished to work less at time t − 1 still wished they worked less at time t. If we condition on working full-time in time t, this rises to about 54 per cent for both groups.

- Considering those who prefer to work more at time t − 1, satisfaction with hours at time t is as common outcome for all groups as a persistent desire to work more hours.

- For those who desire to work less hours at time t − 1, the most common outcome at time t is by far a continued desire to work less hours.

- Part-time workers who prefer to work less hours are likely to leave the labour force in the next wave.

- Unexpectedly, attrition from the sample seems correlated with a desire to work more hours.

However, this attrition is not large enough to explain the difference in persistence of a desire to work less hours compared with a desire to work more hours.

Tables 6 and 7 only show the transitions between working hour satisfaction and dissatisfaction states over one year. Unreported statistics of transitions over a longer period of time show that people with a working hour mismatch are less likely to have the same mismatch as time continues. However, most transitions out of a working hour mismatch occur within one year, as also found by Wooden and Drago (2007). For example, there are 2,805 men who are employed and provide valid responses to the hours preference questions in every wave from the sixth to the tenth (2006–2010). Of these, 898 of them report being overemployed in 2006; 61 per cent of the 898 report also being overemployed in 2007; 45 per cent report being overemployed in each of 2006, 2007 and 2008; 35 per cent report being overemployed in all years from 2006 through 2009; and 29 per cent report being overemployed in all five years from 2006 to 2010.

Persistence: Complexity of the Dynamics

We next examine in more detail the dynamics of those who resolve a mismatch (who go from wanting to work more or less at t − 1 to being content with their hours at time t) and those who develop a mismatch (who report satisfaction with hours at t − 1 and then report dissatisfaction of either type at time t). We begin by looking at the question of what adjusts. Is it working hours that change or is it preferred hours that change. Recall that working hour satisfaction is only one aspect of overall job satisfaction and that it may depend upon other aspects of the job. Suppose that one goes from having an unpleasant boss to a pleasant boss without changing jobs or actual working hours. In this case, preferred hours may adjust, and the dissatisfaction with working hours may be resolved without changing actual hours worked.

Table 8 examines the average change in hours for those who develop a mismatch (rows one and two) and those who resolve a mismatch (rows three and four). Men are considered in columns 2 through 4 and women in the last three columns. For those who desire more hours at time t − 1 and resolve this mismatch in time t, actual hours worked increase by much more (twice as much for men; four times as much for women) than preferred hours change. So this group appears to resolve a mismatch by working more. For all other groups, we see that the adjustment of preferred hours is larger than the change in actual hours. Thus, a desire for fewer hours is generally resolved by a larger change in preferred hours than in actual hours worked. Likewise, the development of either type of mismatch is driven more by changes in preferred hours than changes in actual hours.

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in actual hours | Change in preferred hours | Number of workers | Change in actual hours | Change in preferred hours | Number of workers | |

| Developed desire for fewer hours | 4.0 | −8.7 | 3,969 | 4.2 | −7.5 | 3,377 |

| Developed desire for more hours | −4.4 | 6.6 | 1,792 | −3.7 | 6.3 | 2,011 |

| Resolved a desire for fewer hours | −4.3 | 8.6 | 3,853 | −5.0 | 6.8 | 3,157 |

| Resolved a desire for more hours | 7.4 | −3.6 | 2,168 | 8.1 | −2.2 | 2,307 |

- Note: Differences between the magnitude in the change in actual hours and the change in preferred hours is statistically significant for each group.

Averages can mislead. Tables 9 and 10 are an attempt to demonstrate the richness of patterns that are actually observed in the data for men and women, respectively. In columns 2 and 3, we examine the patterns of changes in actual hours and preferred hours for those who develop an hours mismatch. In columns 4 and 5, we examine the same patterns for those who resolve a mismatch. What we observe is that preferred and actual hours often move together, something not readily visible from Table 8. What we can also observe is that most mismatches are either resolved or created by preferred and actual hours both moving together rather than by just one or the other changing.

| Developed a desire for: | Resolved a desire for: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fewer hours | More hours | Fewer hours | More hours | |

| PH↑ AH↑ | 8.7 | 23.4 | 18.8 | 24.2 |

| PH↑ AH· | 0 | 23.9 | 25.7 | 0 |

| PH↑ AH↓ | 0 | 25.3 | 35.7 | 0 |

| PH· AH↑ | 10.2 | 0 | 0 | 12.4 |

| PH· AH· | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PH· AH↓ | 0 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 0 |

| PH↓ AH↑ | 34.2 | 0 | 0 | 24.7 |

| PH↓ AH· | 27.5 | 0 | 0 | 22.7 |

| PH↓ AH↓ | 19.5 | 14.5 | 8.6 | 15.9 |

| Number of observations | 3,969 | 1,792 | 3,853 | 2,168 |

- Notes: Column percentages sub to 100 subject to rounding. Preferred hours (PH) can increase (↑), decrease (↓) or remain unchanged (·), and the same is true for actual hours (AH), giving nine possibilities.

| Developed a desire for: | Resolved a desire for: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fewer hours | More hours | Fewer hours | More hours | |

| PH↑ AH↑ | 12.3 | 25.8 | 19.7 | 31.3 |

| PH↑ AH· | 0 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 0 |

| PH↑ AH↓ | 0 | 25.6 | 34.5 | 0 |

| PH· AH↑ | 9.6 | 0 | 0 | 12.9 |

| PH· AH· | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PH· AH↓ | 0 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 0 |

| PH↓ AH↑ | 31.7 | 0 | 0 | 26.8 |

| PH↓ AH· | 26.5 | 0 | 0 | 14.9 |

| PH↓ AH↓ | 19.8 | 17.4 | 14.2 | 14.1 |

| Number of observations | 3,377 | 2,011 | 3,157 | 2,307 |

- Notes: Column percentages sub to 100 subject to rounding. Preferred hours (PH) can increase (↑), decrease (↓) or remain unchanged (·), and the same is true for actual hours (AH), giving nine possibilities.

For example, in Table 10, we can see that for women a desire for more hours is resolved by a change only in preferred hours in 14.9 per cent of cases, by a change only in actual hours in 12.9 per cent of cases and by a change in both in the vast majority (72.2 per cent) of cases. Simple intuition might suggest that a desire to work more hours is resolved by working more hours, but at least in its simplest form this is the least likely way in which such a mismatch is resolved.

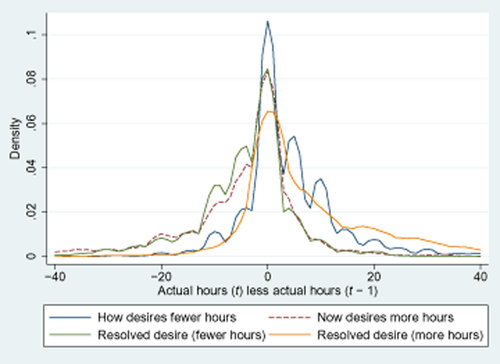

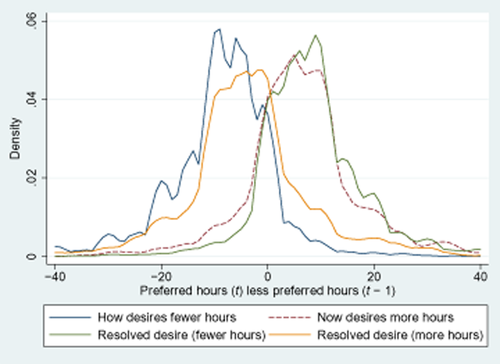

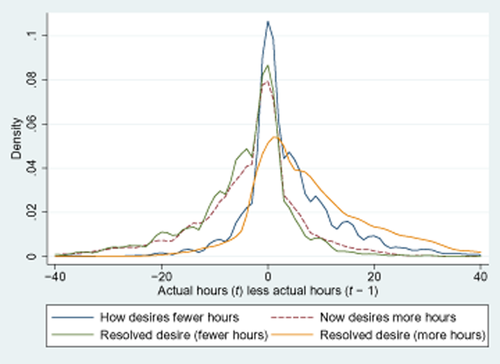

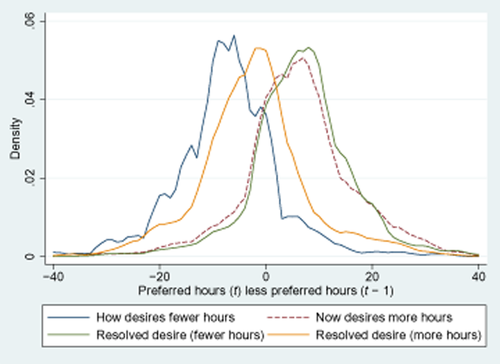

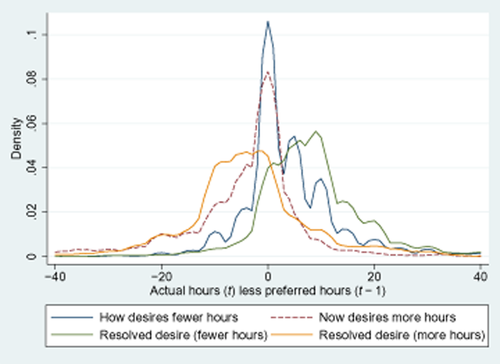

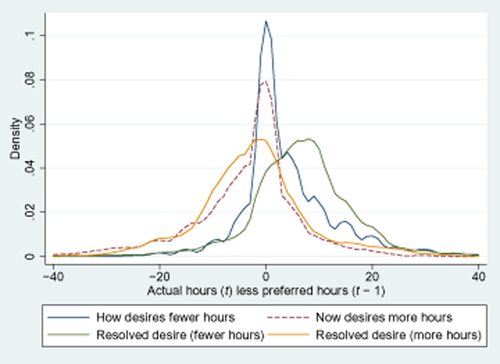

Figures 3 and 4 (for men) and Figures 5 and 6 (for women) further elaborate on this complexity. In these figures, we present non-parametric density estimates of the changes in actual and preferred hours for the four groups considered in Tables 8-10. We again can see the wide variety of experiences documented in Tables 9 and 10, where a change in both preferred and actual hours for all four groups is the norm.

Change in Hours Worked for Males Developing and Resolving Mismatches

Change in Preferred Hours for Males Developing and Resolving Mismatches

Change in Hours Worked for Females Developing and Resolving Mismatches

Change in Preferred Hours for Females Developing and Resolving Mismatches

Figure 7 (for men) and Figure 8 (for women) examine the difference in actual hours at time t and preferred hours at time t − 1 for the four groups that either resolve or develop a mismatch. This difference is largest (in positive terms) for those who resolve a desire for fewer hours. It takes on the largest negative values for those who resolve a desire for more hours. Both groups that develop mismatches are more centred around zero, indicating a smaller shift from past preferred hours to current actual hours.

Difference in Actual Hours (t) and Preferred Hours (t − 1) for Males Developing and Resolving Mismatches

Difference in Actual Hours (t) and Preferred Hours (t − 1) for Females Developing and Resolving Mismatches

Across all six figures, the differences between men and women are again very small.

Persistence: The Role of Changing Employer

As mentioned above, persistent mismatch may be viewed as indicating some type of rigidity in the labour market. If people can freely change jobs to improve their working conditions and move from a situation of dissatisfaction to one of satisfaction, then this would be a strong argument against public policy intervention.

In this subsection, we reexamine the question of transitions across wave between different states of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with working hours. We constrain ourselves to those who are employed in both periods, and we separately analyse those who change employers/jobs and those who stay with the same employer/job (as defined in Section 3.4).

Tables 11 and 12 are laid out in the same fashion as Tables 6 and 7. Looking at full-time employed males, we can see that changing employers between periods greatly facilitates resolving a desire to work less. Of full-time employed males who wished to work less, 65.5 per cent still felt that way a year later if they were with the same employer. Among those who changed employers, only 42.6 per cent now felt this way. Meanwhile, 32.2 per cent resolved a desire to work less hours without changing employer, whereas this number jumps to 46.9 per cent for those who changed employer.

| (A): Transitions of All Male Workers—All Waves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | |||||

| Same employer both periods | Changed employer between periods | |||||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 64.7 | 18.1 | 7.8 | 41.9 | 18.3 | 12.0 |

| Current hours okay | 32.7 | 74.0 | 45.0 | 47.2 | 67.4 | 50.9 |

| Prefer to work more | 2.6 | 7.9 | 47.2 | 11.0 | 14.3 | 37.1 |

| Observations | 9,749 | 18,533 | 3,468 | 1,422 | 2,839 | 1,169 |

| (B): Transitions of Full-Time Male Workers—All Waves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | |||||

| Same employer both periods | Changed employer between periods | |||||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 65.5 | 19.3 | 8.3 | 42.6 | 19.6 | 12.5 |

| Current hours okay | 32.2 | 74.1 | 48.1 | 46.9 | 66.9 | 46.3 |

| Prefer to work more | 2.3 | 6.5 | 43.6 | 10.4 | 13.5 | 41.2 |

| Observations | 9,500 | 15,913 | 1,886 | 1,376 | 2,348 | 541 |

| (C): Transitions of Male Part-Time Workers—All Waves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | |||||

| Same employer both periods | Changed employer between periods | |||||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 37.1 | 10.3 | 7.1 | 20.4 | 12.1 | 11.5 |

| Current hours okay | 51.4 | 73.3 | 40.8 | 52.1 | 70.0 | 55.0 |

| Prefer to work more | 11.5 | 16.5 | 52.2 | 27.6 | 17.9 | 33.5 |

| Observations | 249 | 2,620 | 1,582 | 46 | 491 | 628 |

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are part-time at t − 1.

| (A): Transitions of All Female Workers—All Waves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | |||||

| Same employer both periods | Changed employer between periods | |||||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 61.7 | 17.6 | 8.1 | 39.1 | 19.2 | 11.4 |

| Current hours okay | 34.9 | 72.8 | 46.0 | 48.5 | 63.6 | 51.2 |

| Prefer to work more | 3.5 | 9.6 | 45.9 | 12.4 | 17.2 | 37.4 |

| Observations | 7,349 | 16,601 | 3,777 | 1,158 | 2,537 | 1,187 |

| (B): Transitions of Female Full-Time Workers—All Waves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | |||||

| Same employer both periods | Changed employer between periods | |||||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 65.8 | 23.8 | 8.2 | 41.2 | 22.4 | 9.9 |

| Current hours okay | 31.6 | 71.3 | 60.2 | 46.5 | 63.6 | 43.8 |

| Prefer to work more | 2.6 | 4.9 | 31.6 | 12.3 | 14.0 | 46.2 |

| Observations | 6,178 | 8,026 | 451 | 969 | 1,317 | 179 |

| (C): Transitions of Part-Time Female Workers—All Waves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status this period (t) | Preference last period (t − 1) | |||||

| Same employer both periods | Changed employer between periods | |||||

| Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | Prefer to work less (%) | Current hours okay (%) | Prefer to work more (%) | |

| Prefer to work less | 38.8 | 11.2 | 8.0 | 26.2 | 15.4 | 11.7 |

| Current hours okay | 53.2 | 74.5 | 43.8 | 60.5 | 63.7 | 52.7 |

| Prefer to work more | 8.1 | 14.3 | 48.2 | 13.3 | 20.9 | 35.6 |

| Observations | 1,171 | 8,575 | 3.326 | 189 | 1,220 | 1,008 |

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are part-time at t − 1.

The result is similarly dramatic if we look at part-time males who wish to work more. Of these, 52.2 per cent reported the same problem if they stayed with the same employer, whereas the desire to work more was only reported for 33.5 per cent who changed employer. Of those who changed employer, 55 per cent resolved the desire to work more hours, whereas only 40.8 resolved the problem without changing employer.

For women, the results are similar. Full-time employees resolved a desire to work less 46.5 per cent of the time when changing employer and only 31.6 per cent of the time if they stayed with the same employer. Part-time women resolved a desire to work more 52.7 per cent of the time when changing employers, and only 43.8 per cent of the time when not changing employers.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

It seems clear that the problem of working too much is a bigger problem than that of working too little. Our simple analysis above shows that a desire to work less hours is more common, more severe in terms of the gap between actual and desired hours, and more persistent than the problem of wanting to work more hours. These overarching conclusions are the same for men and women. Once we account for the vastly different proportions of men and women in full-time and part-time work, men and women look very similar within those categories.

One public policy implication that is immediately clear from this analysis is that any policy that tries to better align worker preferences about working hours with their actual working hours is likely to decrease labour supply rather than increase labour supply. If increasing labour supply is the objective, then this is not the right place to look. Media discussion of part-time workers who wish to work more should be balanced with discussion of workers who are working full-time (or more) hours and who would like to work less.

Even on the basis of societal welfare, this looks like a poor target for policy intervention. Our argument is partially based upon what we know about government intervention in labour markets and partially based upon our data analysis presented above.

Considering first the data, the fact that most mismatches are resolved when we look one year later provides a strong argument against policy intervention. Full-time workers who prefer to work less are the only group for whom this is not true, and the persistence is just over 50 per cent for this group. If we look over longer intervals, this persistence decreases in a predictable way. Over a five-year span, about 29 per cent of full-time workers report a desire for fewer hours in all years.

Clearly, some workers are able to resolve mismatches. The evidence on the impact of changing employers indicates one way in which this happens. Workers resolve mismatches at a rate that is 10–20 percentage points higher when they change employers than when they do not change employers. Policies that lower the rate at which people change jobs, such as those that impose high hiring or firing costs on firms, will make it harder for workers to resolve mismatches.

Without ignoring the fact that some workers are unhappy about their working hours and that it is persistent for some people, we would still argue against public policy intervention on other grounds not directly based upon our data.

Government intervention in labour markets can be highly distortionary. It is hard to imagine an intervention in this case that would not impose costs on both employers and employees. These costs would raise the cost of working (shifting labour supply to the left) and the cost of hiring (shifting labour demand to the left). This would have an ambiguous effect on wages but an unambiguous, negative effect on employment. Furthermore, intervention would distort behaviour. Firms might choose not to hire part-time workers if they believe that the government will try and force them to convert these workers into full-time workers, which might decrease employment. A subsidy program to convert part-time workers to full-time workers might have the opposite effect where employers only hire part-time workers in order to reap the benefits of the subsidy. Such a policy could quickly become very costly as it would have to be paid on all employees, but the effect would only be on a small margin who would have persisted as underemployed in the absence of the subsidy. Any policy would also necessarily remove the ability of workers to trade off job characteristics. Some people may put up with hours they do not like for other benefits (either currently or in the future), and any policy would necessarily restrict an individual's ability to make these types of choices.

A more complete understanding of the problem of working hour mismatch requires econometric modelling and would allow for variation in the conditional probabilities of mismatch. Allowing this probability to vary over time, demographic characteristics and job characteristics could allow for a deeper understanding of welfare and inequality issues related to working hour mismatch. Even in this case, the first step in running sensible regression models is a thorough understanding of the data.

One can quibble about our rather dismal view towards government intervention, but the added benefit of being able to better understand the nature of policy problems provided by the presence of panel data seems undeniable. We also would like to draw the reader's attention to the fact that even in the absence of the type of regression modelling discussed above, our approach provides a much enhanced view of our understanding of the problem. We think that there is large scope within government policy circles and agencies to make better use of existing data sources to undertake more complicated descriptive analyses of public policy problems following the basic outline of this article.

Footnotes

Footnotes

Appendix 1

| Source | Date | Sample | Survey question wording and key definitions | Hour mismatch response statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Bureau of Statistics (2007): 6361.0 Survey of Employment Arrangements, Retirement and Superannuation (SEARS) | 2007 | Approximately 16,000 households; for 85 per cent of these everyone in scope for the survey (aged 15 and over) answered the entire survey. The final sample of individual responses was 26,972. |

‘If you could choose the total number of hours you work each week, and taking into account how that would affect your income, which of these options would you prefer?’ There are three options: (1) ‘Fewer hours than you work now; (2) ‘About the same hours as you work now’; (3) ‘More hours than you work now’ Underemployment and overemployment are defined on the basis of the responses to these questions. |

Prevalence: 14 per cent of the sample underemployed, 21 per cent overemployed (weighted to population). Severity: N/A Persistence: N/A |

| Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) (and earlier issues): 6265.0 Underemployed Workers | Annual from 1996–2011 | In 2011, the sample size was 29,818 employed individuals over the age of 15 from 27,365 households. |

Underemployed workers are defined as employed people who would prefer, and are available for, more hours of work then they currently have. They are comprised of part-time workers available to start work with more hours, either in the reference week or in the four weeks subsequent to the survey and full-time workers who worked part-time hours in the reference week for economic reasons (e.g. having been stood down or lack of sufficient work). Only underemployed part-time workers were asked: ‘Would you prefer to work more hours than you usually work?’ Before 2008, the question was ‘Would you prefer a job in which you worked more hours a week?’ |

This study looks only at underemployment, not at overemployment. All statistics taken from the September 2011 figures: Prevalence: 6.8 per cent of workers were underemployed in September 2010 (weighted to population). 91.8 per cent of the underemployed were ‘part-time underemployed’ and 8.2 per cent were ‘full-time’ unemployed Severity: Mean of 14.1 extra hours preferred by the part-time, underemployed population. Persistence: Mean duration of 68 weeks (median 30 weeks) of current underemployment spell for part-time workers. |

| van Wanrooy et al. (2009): Australia at Work survey | 2007–2009 | 6,333 individuals surveyed from 2006 to 2009 and 6,081 individuals surveyed in 2009. |

‘Would you like to change the number of hours you currently work?’ Three options for responding are: (1) ‘No, I am happy with my hours’; ‘(2) Yes, I would like to work fewer hours’; (3) ‘Yes, I would like to work more hours’. Underemployment and overemployment are defined on the basis of the responses to these questions. |

Prevalence: In 2009, 8.7 per cent of employed persons were underemployed and 23.9 per cent overemployed (weighted to population). Severity: Capability for survey to address but no analysis available. Persistence: Capability for survey to address but no analysis available. |

| Fear et al. (2010) | 2010 | 1,786 individual responses of which 1,061 were employed. 892 worked in the week of the survey and answered hour preference questions. | ‘How many hours would you prefer to work, taking into account the effect on your income?’ |

Prevalence: 29 per cent of respondents underemployed, 50 per cent overemployed. Severity: The underemployed on average want 9.9 more hours per week, the overemployed want 10.9 fewer hours. The average working hour mismatch across all workers is 2.5 more worked hours than preferred hours. Persistence: N/A |

| Wilson et al. (2006): The Australian Survey of Social Attitudes, Version A | 2005 | 3,902 individuals aged over 18 surveyed with 1,175 in paid work who responded to this question. |

‘Think of the number of hours you work, and the money you earn in your main job, including any regular overtime. If you had only one of these three choices, which of the following would you prefer?’ The three choices are (1) ‘Work longer hours and earn more money’; (2) ‘Work the same number of hours and earn the same money’; (3) Work fewer hours and earn less money’. Underemployment and overemployment are defined on the basis of the responses to these questions. |

Prevalence: 21.7 per cent of respondents underemployed and 10 per cent overemployed (5.5 per cent can't choose) Severity: N/A Persistence: N/A |

| Stone and Hughes (2009): Families, Social Capital and Citizenship project | 2001 | 1,506 respondents older than 18. 951 answered hour preference question (self-employed and non-workers not asked). |

‘Thinking about the number of hours you work each week and including regular overtime, would you prefer working more hours per week, fewer hours per week or about the same?’ Underemployment and overemployment are defined on the basis of the responses to these questions. |

Prevalence: 9.7 per cent underemployed, 41.2 per cent overemployed. Severity: N/A Persistence: N/A |

| McDonald et al. (2009): Negotiating the life course | 1997, 2000, 2003, 2006 | In 2006, 2,296 of 3,138 were employed and in scope for this question |

‘Would you like to change the number of hours you currently work?’ Then three options are provided: (1) ‘Yes, would like to work more hours’; (2) ‘Yes, would like to work fewer hours’; (3) No, happy with present hours. Underemployment and overemployment are defined on the basis of the responses to these questions. |

Prevalence: In 2006, 10.5 per cent underemployed, 28.1 per cent overemployed. Severity: In 2000, Average difference between actual and preferred working hours of 2.8 more worked hours across all workers (van Wanrooy, 2005). Persistence: 26 per cent of the underemployed in 1997 also reported being underemployed in 2000, and 60 per cent of the overemployed in 1997 also reported being overemployed in 2000 (van Wanrooy, 2004). |

References

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are full-time at t − 1.

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are full-time at t − 1.

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are full-time at t − 1.

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Column percentages sum to 100 per cent subject to rounding.

- Workers are full-time at t − 1.