Finteching remittances in paradise: A path to sustainable development

Abstract

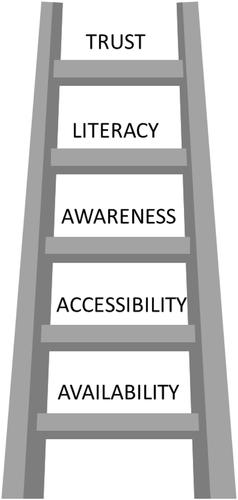

The costs of sending remittances to Pacific small island developing states (SIDS) are among the highest in the world. Tackling this issue is crucial not only for economic and social development, but also for improving financial inclusion. This article analyses fintech adoption in remittance services, namely the adoption of alternative payment methods in transferring money by using the internet or mobile phones, in the Pacific. It introduces an original framework to assess the current landscape of fintech in the remittance sector and draws tailored policy recommendations. The framework is conceptualised through a ladder with five rungs: availability, accessibility, awareness, literacy and trust. Based on the ladder analysis, the authors observe the lack of basic digital infrastructure and digital platforms in many Pacific SIDS. Where the technological landscape is better developed, fintech services have established strong footholds, but there is a need for greater awareness to broaden its appeal and customer base. The benefits of fintech platforms are high, especially in the context of lower remittance costs which constitute an unduly large share of GDP in Pacific SIDS. The basic infrastructure needed to develop fintech services are equally important for the overall sustainable development of Pacific SIDS. The article observes fintech services in the Pacific are a means for financial inclusion of the unbanked, that can accelerate the economic and social development of the SIDS, and countries in the Pacific region are at different stages in their readiness for fintech adoption.

1 INTRODUCTION

Covering less than 1% of the globe surface and roughly 1% of global population, small island developing states (SIDS) are often referred to as ‘paradise on Earth’, due to their scenic landscapes and laid-back lifestyle. However, they are typically characterised by small domestic markets that pose barriers to the development of a dynamic private sector and a competitive economy. SIDS are dependent on imports and are highly exposed to external economic shocks, particularly international financial volatilities. SIDS are 12 times more exposed to oil price-related shocks than non-SIDS (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2012).

The socio-economic fragility of Pacific SIDS results from their remoteness and geographical isolation as well as their vulnerability to natural disasters. Pacific SIDS are situated on average 12,000 km away from the nearest markets, impeding not only trade but international cooperation and integration. According to the World Risk Index 2021, Pacific SIDS are most vulnerable to natural disasters: Vanuatu ranked first worldwide, followed by Solomon Islands and Tonga (Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict, 2021).

A common characteristic of Pacific SIDS is their reliance on remittances. Moreover, the costs of remitting to the Pacific are among the highest in the world, systematically higher than global and other regional averages (World Bank, 2018). Lowering transaction costs, therefore, has the potential of contributing to economic growth and human development of the region. Financing for Development is recognised by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Target 10.c: ‘By 2030, reduce to less than 3 percent the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 percent’ (United Nations, 2015). Meeting this target would save remittance families worldwide around US$20 billion annually (International Fund for Agricultural Development [IFAD], 2017).

Motivated by seeking innovative financing solutions, this article attempts to answer two fundamental questions. First, given such high costs of sending remittances, can financial technologies (fintech) be an instrument to drive costs down? Fintech is defined as alternative payment methods with unconventional access points for transferring money, namely online platforms, blockchain and mobile money. This is further elaborated in Section 4 of the paper. Second, in that case, what needs to be done to widely promote the adoption of fintech in the Pacific? This article applies a ladder framework largely used in political science and economic literature to analyse how to effectively promote fintech in remittance services in the Pacific. Previous studies have focused on the high volume of remittance inflows (Browne & Mineshima, 2007), the high transaction costs (Gibson et al., 2006), the impact of remittances on growth (Feeny et al., 2014), the relation between natural disasters and remittances (Bettin & Zazzaro, 2018), and the potential of remittances to improve financial inclusion using modern digital technology (International Monetary Fund, 2018). None have examined the role of fintech adoption in the context of remittance services in the Pacific.

The article is organised as follows: Section 2 examines the magnitude of remittance flows and their transaction costs. Section 3 presents the causes for costly remittances in the Pacific and discusses the viability of different solutions. Section 4 establishes a definition for fintech-based remittance services. Section 5 introduces a new framework to assess the current state of affairs in the Pacific. Section 6 concludes with a summary of the findings, some policy recommendations and areas for future research.

2 REMITTANCES IN THE PACIFIC

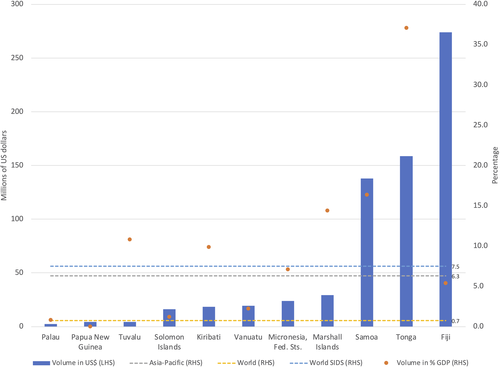

Cross-border remittances, defined as personal transfers of income of employees made by non-resident households to resident households, are a major source of external financing for Pacific SIDS. From 2000 to 2017, Pacific SIDS received an average of 9.7% of their GDP in cross-border remittances—more than the average of world SIDS or the Asia-Pacific region. According to the World Development Indicators, Tonga received the highest level of remittances as a proportion of GDP (37.1%), followed by Samoa, Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and Kiribati (Figure 1). Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Palau are in line with the 2017 world average of 0.7%, barely dependent on remittances. In 2017, around US$688.5 million was sent to the Pacific SIDS via remittance transactions. The largest recipient was Fiji, recording around US$274 million or 40% of the total.1

Personal remittances received in selected countries, 2017. Note: No available data for Nauru at the time of writing. Source: Authors, based on World Bank’s World Development Indicators database. SIDS, small island developing state

Remittances play a crucial role in stimulating private consumption as they are received directly by households. The Financial Services Demand Side Surveys conducted in Samoa, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Tonga reveal that over one-third of adults received remittances from within the country or abroad.2 (For the remainder of this article, Surveys refers to the Financial Services Demand Side Surveys unless otherwise stated.) These large flows of remittances are explained by the high levels of migration to neighbouring countries (Australia and New Zealand), together with a strong communal culture of giving. Browne and Mineshima (2007) reveal that the main drivers for Pacific migration are the economic prosperity of partner countries, direct transport links and the absence of language barriers. Additionally, both Australia and New Zealand have been expanding their seasonal worker programs that bring thousands of Pacific workers into the agriculture, hospitality and tourism sectors.3 Cultural traditions in the Pacific are deeply rooted in family and community values. Workers from the Pacific feel a social obligation to set aside part of their income to support their immediate and extended families. This monetary assistance is used for food, housing, medical and educational expenses, major life events such as weddings or funerals, and to fund livelihoods and in the aftermath of natural disasters.

Remittances contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) primarily by reducing poverty, promoting gender equality, and supporting decent work and economic growth. Research shows that a 10% increase in per capita remittances leads to a 3.5% decline in the share of poor people in the population (IFAD, 2017). In the Pacific, migrants are typically men, with women-headed households relying on remittances. Women recipients are given increased economic empowerment and financial autonomy. Feeny et al. (2014) argue that the size of remittances has a positive impact on real GDP growth through increased investments. Remittances are also found to have a stabilising influence on output and investment volatilities (Jackman et al., 2009).

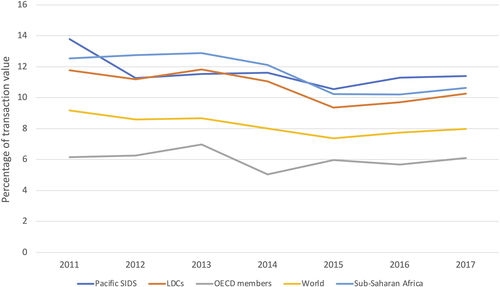

But the transaction costs of sending remittances to the Pacific are among the highest in the world. The average cost of remitting US$200 to the Pacific SIDS from 2011 to 2017 was 11.6% of the transaction value, which is well above the global average of 8.2% (see Figure 2).

Transaction costs of sending remittances, 2011–2017. Note: Not all Pacific small island developing state (SIDS) are included in the dataset—for 2011, data includes Fiji, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu; for the remaining years, data include Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu. Source: World Bank’s World Development Indicators database

Research has shown that remittances have a negative cost-elasticity; that is, the lower the costs of remitting money, the larger the amount of transfers. This is in accordance with the law of demand: the lower the prices, the higher the quantity consumed. Gibson et al. (2006) estimate this negative price-elasticity is around 22%, whereas Freund and Spatafora (2008) found it to be about 16%. Aycinena et al. (2010) concluded that lowering fees by US$1 would boost remittances by US$25 a month in the United States–El Salvador corridor. Migrants care about their relatives and, given the opportunity to save on remittance fees, will choose to send the saved money back to their families rather than keeping it for themselves.

Lowering remittance transaction costs can also contribute to reducing informal transfers from migrants to their families. Informal channels include cash transfers delivered personally or by unofficial couriers, relatives or friends. Money delivered by hand entails greater risk of loss, theft and crime, so reducing remittance informality creates more secure transactions. Economies would also benefit from lower levels of informal remittances, with improved transparency. The smaller the informal sector, the more reliable the national accounts; in turn, improved accuracy in recording financial flows would lead to increased efficiency of regulation and supervision. Not realising the true size of remittance flows could lead to inappropriately designed policy initiatives.

In sum, evidence suggests that a reduction in remittance transaction costs would increase the amount of transfers and reduce informal transactions, guaranteeing a more secure and transparent transfer of migrant funds.

3 CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS TO HIGH REMITTANCE COSTS

There are three main drivers of costly remittances in the Pacific region: (i) small size of transfers; (ii) de-risking practices; and (iii) the geography of SIDS.

First, the volume of money sent back by Pacific islanders in a single transaction is typically small. Data shows that 75% of remittances to Pacific countries were less than US$330, significantly lower than the global average (AUSTRAC, 2017). This results in high remittance costs because most remittance service providers (RSPs) charge a fixed minimum fee.

Second, the remittance industry in the Pacific is facing the threat of de-risking practices imposed by global financial institutions, which are increasingly terminating or restricting their business relationships with remittance companies and smaller local banks (Alwazir et al., 2017). These practices are driven, on the one hand, by cost-benefit considerations that inevitably make small countries with limited financial markets more vulnerable. On the other hand, weaknesses in government policies regarding anti-money laundering and the combat of terrorism financing (AML/CTF) make Pacific island countries riskier and less attractive. There is a need for stronger regulatory action regarding AML/CTF obligations in the Pacific. During 2018, discussions between banks, money transfer operators and regulators were held in the Pacific in cooperation with the International Monetary Fund and the Asian Development Bank (2018). In these discussions, the parties agreed to pursue strategies for better information sharing and focus on automation and technology to improve customer due diligence.

Third, operating in the Pacific can be very costly for RSPs due to the small size of many of the islands and infrastructure gaps, resulting in expensive distribution channels which make it hard to achieve economies of scale. The small and widely dispersed populations of Pacific SIDS make it unattractive for companies to operate. In the Solomon Islands, for example, unbanked individuals live on average 6 hours away from the nearest bank branch (Central Bank of Solomon Islands, 2015). Apart from long distances, bank branches are often hard to access, as revealed by the 29.2% of Solomon Islanders who reported needing a canoe or an outboard motor engine to reach their branch. These geographical barriers to accessing a branch reinforce the gender gap in financial inclusion, as female Solomon Islanders are significantly less likely to be banked (Central Bank of Solomon Islands, 2015).

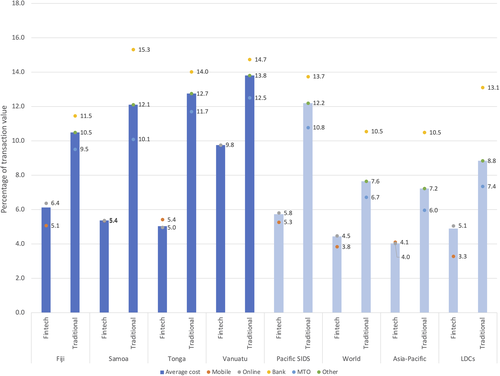

In an attempt to deal with the costs of geographical isolation and infrastructural constraints, finance companies have started combining innovative business models and technology. These so-called fintech companies, whose main objective is to enable, enhance and disrupt financial services, are competitive due to their ability to reduce operational costs by using digital platforms and minimising office rent and labour costs. They also use fewer intermediaries in any transaction (Cortina & Schmukler, 2018). Hence, fintech companies systematically charge lower remittance fees than traditional RSPs (Figure 3). Mobile money services are usually the most affordable, followed by online platforms. Money transfer operators and banks provide, as expected, the most expensive services. As the number of fintech companies operating in the region continues to grow, competition from fintech companies will put more pressure on traditional RSPs to charge lower fees.

Average costs of sending remittances by service provider (2016Q2–2018Q4). Note: Money Transfer Operator (MTO); the category ‘Other’ includes post offices, building societies and other non-bank financial institutions; blockchain-based remittance service providers are not covered by the data. Source: Authors, based on the World Bank’s Remittance Prices Worldwide database. SIDS, small island developing state

Fintech remittance services can also promote financial inclusion. Financial inclusion refers to the proportion of the population that participates in the financial system, and is often proxied by account ownership. Fintech remittance services are not cash based, they require a formal account. Therefore, if individuals perceive the cost benefits of fintech-based remittances and are incentivised to contract these services, they will open an account and become part of the financial system. Fintech remittances also contribute to women’s empowerment by giving women more control over family finances and increasing their personal security. Digital wallets give recipients greater control over how the money received is used by preventing other household members from easily accessing it. Digital payments enable the confidentiality and convenience women require in using financial services. Research has shown that the arrival of mobile money transfers increased women’s economic empowerment in rural areas of Kenya (Morawczynski & Pickens, 2009).

Given the importance of remittances in families’ daily lives, fintech transfers could trigger people’s trust in the digital economy, encouraging them not only to set up an account but also to build savings, pay bills and access credit. International Monetary Fund (2018) found evidence that the spread of mobile technology has a positive effect in improving access to banking services such as deposit accounts and bank loans.

Fintech implementation should therefore be placed on the Pacific policymakers’ agenda. Not only does it contribute to the affordability of remittance transactions, it also facilitates financial inclusion. The combination of these factors demonstrate that fintech services are an important catalyst for the sustainable development of local communities, as advocated in the 2030 Agenda.

4 TYPES OF FINTECH REMITTANCE SERVICES

Fintech in remittances is the adoption of alternative payment methods such as the internet or mobile phones for transferring money. Traditional remittance service providers include institutions whose services are contracted through bank branches, brick-and-mortar agents or call centres. What differentiates these two is the access point from which services are made available. There are three business models for cross-border fintech remittances: online platforms (including peer-to-peer platforms); blockchain-based technology; and mobile money operations (Alliance for Financial Inclusion [AFI], 2018).

The term ‘online platforms’ refers to companies that exclusively provide online remittance services via mobile applications or websites.4 To transfer money, senders must link their bank accounts to the platform, while receivers can get the funds in several ways (including cash). Some online platforms operate under a peer-to-peer model. This allows money to be received in a different currency from the one sent without the funds actually crossing borders. If someone is buying dollars with euros and another customer is buying euros with dollars, the two transactions would be paired by using two local transfers instead of one international transaction, allowing RSPs to charge the official exchange rates which greatly reduces transaction costs.

Another business model for remittances enables money transfers through cryptocurrencies—that is, decentralised currencies created under blockchain technology. Some widely used digital currencies are Bitcoin, XRP and Ethereum. Blockchain-based RSPs should not be confused with cryptocurrency exchanges. In fact, contracting these services does not imply any volatility risk for the customer, as the recipient never deals with the cryptocurrency (Buenaventura, 2017). The whole process works as follows: an ‘on-ramp’ company in the sending country which accepts local fiat currency converts the funds into cryptocurrency; subsequently, that company transmits the digital cryptocurrency to an ‘off-ramp’ company in the receiving country, which then converts it into the local currency and delivers the funds to the final beneficiary via a variety of domestic transfer mechanisms.

Mobile money services are another example of how technology can improve the efficiency of financial transactions. They are usually provided by mobile network operators and consist of electronic wallets linked to the customer’s mobile phone number. With these e-wallets, individuals can transfer funds, pay bills, and deposit and withdraw cash using their mobile phones. Customers do not need internet access or a smartphone—electronic wallets also work through regular mobile phones with mobile-cellular network connectivity. The main advantage of these products is that no formal bank account is necessary to open a mobile money account, making it accessible to a greater share of the population.

5 THE LADDER OF FINTECH-BASED REMITTANCE SERVICES

This article has discussed the issue of costly remittance corridors in the Pacific SIDS and proposed a viable way of overcoming it through the adoption of fintech services. The next step is to understand what needs to be done in the region to encourage more adoption of fintech services. For this, it is necessary to explore whether there are fintech companies operating in the Pacific remittance corridors and, if so, whether Pacific islanders are using these services.

Survey data shows that 72% of Fijians and 92% of Samoans receive money from abroad through traditional operators such as Western Union. About 83% of Tongans who receive international remittances use Western Union’s services alone, which charges some of the highest transaction fees. This pattern is also evident in other Pacific SIDS such as Vanuatu and Samoa where bank transfers and hand delivery of cash are the second and third most popular cash transfer mechanisms. Data on cash transfers are unreliable and tend to systematically underestimate the true volume. The widespread use of cash transfers continues, as reflected in the behaviour of seasonal workers from the Pacific working in Australia who save cash and carry it back home with them. Less than 10% of households reported using mobile money or electronic methods to receive money from within or outside their country. This reflects the still underdeveloped demand for fintech-based remittances (see Central Bank of Samoa, 2015; Central Bank of Solomon Islands, 2015; National Reserve Bank of Tonga, 2016; Pacific Financial Inclusion Programme [PFIP], 2016; Reserve Bank of Fiji, 2015; Reserve Bank of Vanuatu, 2016).

An assessment framework for the presence of fintech in the remittance sector is, therefore, necessarily presented. The ‘ladder of fintech-based remittance services’ approach highlights actions that need to be developed to encourage fintech adoption. Figure 4 outlines the path that needs to be followed by remitters to change behaviour towards fintech and away from traditional services. The framework is conceptualised through a ladder with five rungs. To get to the top, that is actual adoption of fintech-based remittance services, the previous rungs must be climbed. This framework is designed to reflect the consumer’s perspective, not the company’s.

The ladder of fintech-based remittance services. Source: Authors

Ladder frameworks are widely used in political science and economic literature. Arnstein (1969) introduced this concept in her work on citizen participation in government decision-making. As citizens progressed up the eight-rung ladder, their power in determining the outcome of the decision-making process increased. Muzzini (2005) later adopted the ladder in her study on consumer participation in the regulatory process of infrastructure. References to ladder schemes have also been used by Hosier and Dowd (1987) in the ‘energy ladder’, which sets a hierarchical relationship of four fuel types used by households and income category, with individuals consuming cleaner and more efficient energy sources as their income improves. Grilo and Thurik (2005) also used the ladder framework to define entrepreneurship, where higher steps correspond to higher levels of entrepreneurial engagement.

The ladder defined in this article shares some common features with previous studies. Successive rungs of the ladder correspond to progressively higher degrees of individual engagement in the process of accepting fintech. The fintech ladder follows a chronological progression. Rungs cannot be leapfrogged and the outcomes are binary. Individuals either use fintech-based services or they do not. If the consumer is on the fourth rung, they will still not use fintech. But they will likely be more engaged, that is closer to adopting fintech, than a first-rung individual.

The first rung of the ladder is availability. If there are no companies providing fintech services, the question of how to boost demand is moot.

The number of online platforms currently operating in the Pacific SIDS is shown in Table 1.5 Fiji, Samoa and Tonga are the best served countries in the region, with five or more fintech companies operating in each country. These figures are above the national average number of online platforms operating in the world (3.9), but below that of the Asia-Pacific region (7.2).6 However, in Kiribati and Tuvalu, only one online platform exists. The most widely used platforms in the Pacific are Compass Global Markets, XE Money Transfer and Xendpay. They are present in six or seven of the eight Pacific SIDS; whereas, ‘Ave Pa’anga Pau and OrbitRemit are present in only one country each—Tonga and Fiji, respectively.

| Fiji | Kiribati | Papua New Guinea | Samoa | Solomon Islands | Tonga | Tuvalu | Vanuatu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ave Pa’anga Pau | • | |||||||

| Compass Global Markets | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| KlickEx Pacific | • | • | ||||||

| OrbitRemit | • | |||||||

| WorldRemit | • | • | • | |||||

| XE Money Transfer | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Xendpay | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

- Abbreviation: SIDS, small island developing state.

- Source: Authors, based on SendMoneyPacific (2019).

To date there are no blockchain-based RSPs, which allow money transfers through cryptocurrencies, in the Pacific. The first start-ups operating under this business model appeared around 2014 in some Southeast Asian countries, serving the remittance corridors to the Philippines (Buenaventura, 2017). Ever since, the volume transacted has grown, but has barely expanded to other parts of the globe. This might be due to unclear or lack of regulations concerning cryptocurrencies. Generally, Pacific monetary authorities have publicly disapproved of any activities involving Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies.

Cross-border mobile money providers first appeared in the Pacific around 2010 in Fiji and have since expanded into PNG, Samoa and Tonga. As shown in Table 2, there are two mobile money providers in Fiji (Digicel and Vodafone) and one in PNG, Samoa and Tonga (Digicel). Mobile money operators typically allow the transfer of funds on a national basis only. If remitters wish to send money abroad, they need to contract the services of international mobile money platforms (provided they have business agreements with the local providers). In Fiji, for instance, individuals have at their disposal three platforms (RocketRemit, KlickEx Pacific and WorldRemit) depending on the mobile money product used by the recipients of the money. Sending remittances via mobile money to PNG, Samoa and Tonga is only possible with KlickEx Pacific. And while mobile money products exist in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu (ANZ GoMoney Pacific), those countries do not allow cross-border transfers meaning they cannot be used by remittance dependent households. There are no mobile money providers in the remaining islands of the Pacific.

| Mobile money provider (mobile money product) | Fiji | Papua New Guinea | Samoa | Tonga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digicel (Digicel Mobile Money) | RocketRemit | KlickEx Pacific | KlickEx Pacific | KlickEx Pacific | KlickEx Pacific |

| Vodafone (M-PAiSA) | WorldRemit | ||||

In sum, both online platforms and mobile money providers are available in some Pacific SIDS. On the other hand, there are no blockchain-based RSPs operating in the region. For this reason, further ladder analysis of blockchain-based RSPs is unnecessary from the consumer perspective.

Ensuring an adequate supply of fintech-based remittance services is, however, not sufficient to understanding the adoption of fintech services. As discussed earlier, there is still a strong preference for traditional remittance services despite the presence of fintech companies in the countries. Therefore, further examination of this situation is warranted through the second rung of the ladder which is the degree of accessibility.

Online platforms require internet connection and a device which allows internet browsing. Based on global statistics, the number of fixed broadband subscriptions in the Pacific is small, an indicator of the low usage levels of personal computers. Similarly, smartphone penetration rates are also very low, below 10% (PFIP, 2018). In 2017, only about 33% of the Pacific population was using the internet, compared to 49% worldwide and 79% in OECD member states, according to the World Development Indicators.

However, mobile money is readily accessible to most Pacific islanders. To utilise mobile money, customers need a mobile phone (not necessarily a smartphone) and an active SIM card with access to a 2G network, a requirement met by the majority of the Pacific population. Survey data shows that in Fiji, Samoa and Tonga, 76, 71 and 77% of respondents own a mobile phone, respectively. This implies that among all fintech categories, these Pacific countries could readily adapt to mobile money services.

For effective usage of online services, internet adoption must be more widespread in the region. On the other hand, given that the majority of the population has relatively easy access to mobile money services, further ladder analysis will only consider this last category of fintech, particularly in those countries where mobile money providers operate internationally (Fiji, Samoa and Tonga).

The third rung of the ladder is awareness. Fintech services might be available to Pacific islanders, but unless people know about their existence, individual behaviour will not change. The Financial Services Demand Side Surveys investigated the level of awareness of mobile money services among Pacific SIDS and found that in Samoa less than 40% of the respondents had heard of mobile money. In Tonga and Fiji, the challenge is to move beyond awareness: although people know about these services, the rates of mobile money account ownership are still low. The Surveys also reveal that, in Fiji, 80% of individuals had heard of mobile money, compared to 69% in Tonga. However, only 7% and 10% of respondents reported having a mobile money account in Fiji and Tonga, respectively.

Lack of product understanding further explains why people who are aware of mobile money may not use it. Literacy is the fourth rung. Educating people about mobile money should be a priority for three reasons. First, individuals must see the value and benefit of using mobile money services. These benefits include lower transaction costs, lower access costs (commuting time is reduced), increased security and faster speed in receiving funds. Second, it is important that consumers understand how mobile money accounts work. In Samoa, 36% of Survey respondents who had heard of mobile money reported that they did not know how to use it. A dedicated survey on Fijian consumer perception towards mobile money asked about factors that would persuade already informed respondents to use mobile money services. Around 30% answered, ‘provide training at public gatherings’, and over 55% answered, ‘provide more information on how to use the service through radio and television’ (PFIP, 2012). Third, improving the levels of literacy also implies correcting some misconceptions. In Samoa, one focus group respondent admitted they would not use mobile money services because of a fear that losing their phone would result in losing their money (PFIP, 2016). The reality, however, is that there are personal access codes that protect mobile money accounts, and customer support services available to help alleviate this concern.

Financial education campaigns can be a vehicle to promote better understanding of fintech services. Education needs to be aimed at both children and adults. Some countries, namely Fiji and Vanuatu, have already incorporated financial education content in national school curricula. In PNG and Solomon Islands, pilot programs are being implemented; and in Samoa and Tonga, plans are under discussion. For adults, financial education campaigns can take the form of workshops or online and continuing learning. The Reserve Bank of Fiji released in 2017 its first financial education television show, in collaboration with the Fiji Broadcasting Commission, entitled Noda i Lavo (Our Money), covering a range of topics including remittances.

The last rung of the ladder is trust. This is the ultimate step of using fintech-based remittance services. Understanding how a service works and recognising its advantages is not sufficient to convince people to start using fintech-based services. It is essential that potential customers perceive the mechanisms and their providers as trustworthy.

Economies of the Pacific are extremely cash-oriented, which helps explain the hesitation of Pacific islanders in adhering to digital transactions. According to the Financial Services Demand Side Surveys, 89% of Fijian and 57% of Samoan respondents prefer to use cash instead of electronic payments; in these two countries, respondents justified this preference by saying that cash was more convenient and easier. The prevalence of cash is also observed in Tonga, where 98% of adults pay school fees in cash. The way workers get their salaries can be a key driver for this phenomenon. In Tonga, 96% and 70% of agricultural and private income, respectively, are received in cash (National Reserve Bank of Tonga, 2016).

Another obstacle to potential customers taking a step onto the trust rung can be unfamiliarity with the fintech companies. When asked whether they would like to try mobile money, Samoans answered that they were concerned about the ‘dishonesty of people or agents to who the money is sent to’ (PFIP, 2016). In Fiji, over 50% of respondents reported not trusting mobile money agencies to provide a good service (PFIP, 2012).

Applying the ladder framework to the Pacific SIDS answers the question of why remittance families have avoided the more affordable fintech services. In the case of blockchain-based RSPs, the problem lies in the unavailability of these services. Online platforms, however, are not widely used largely because of accessibility reasons. Mobile money services, therefore, are the type of fintech with the highest potential in the Pacific SIDS. Their wider use is unfortunately hindered by a lack of awareness, financial literacy or trust, depending on the country.

6 POLICY IMPLICATIONS

As Pacific SIDS are in various stages of digital development, different policy actions are needed to promote fintech adoption/implementation, accounting for differences in each Pacific country. The promotion of all types of fintech is desirable, as each type brings key benefits to remitters, not to mention that increased competition will drive down costs. It is, therefore, recommended that policymakers provide an enabling ecosystem for both supply and demand for fintech services to flourish—that is, remove the obstacles of each rung of the ladder.

Table 3 summarises the key measures for Pacific countries to promote the widespread use of fintech-based remittances. Priority areas are highlighted by a bullet point and often more than one policy action is required. The countries where fintech services are non-existent or very limited are grouped in one column. The remaining columns outline six Pacific SIDS with respect to fintech services availability by degree of development and the different rows represent policy related to the five rungs.

| Rungs of the ladder | Key policy considerations | Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu | Solomon Islands | Vanuatu | Papua New Guinea | Samoa | Tonga | Fiji |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | Support an innovative business environment | • | ||||||

| Foster cross-border mobile money services | • | • | ||||||

| Accessibility | Improve network performance | • | • | • | ||||

| Invest in basic infrastructure and devices | • | |||||||

| Awareness | Adopt ‘below-the-line’ marketing campaigns | • | ||||||

| Literacy | Promote financial education campaigns | • | ||||||

| Trust | Implement government-to-person digital transfers | • | • | |||||

| Focus on reaching rural areas | • |

- Abbreviation: SIDS, small island developing state.

- Source: Authors.

Fintech transfer operators are still not available in many countries of the region. Online platforms, for example, do not operate in Nauru, Palau, Federated States of Micronesia or Marshall Islands and competition is limited in Kiribati and Tuvalu. Given the importance of remittances in these economies (except in Nauru and Palau), policymakers should ensure a supportive business environment to foster online platforms. A first step would be to recognise the contributions to the remittance market of non-financial sector players through adequate licensing. Standardised and transparent licensing criteria is essential to facilitate business planning and encourage investment. In their sample of 15 countries from various regions, AFI (2018) found that only three had regulatory frameworks that allowed non-bank institutions to provide digital cross-border remittance services. Moreover, relevant laws and regulations should not change often and should be consistently enforced by the authorities. These measures would promote mobile money services in countries where fintech services are not yet available.

The scenario is different in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, where mobile money operators already operate domestic transfers. Policymakers in these countries should prioritise the promotion of low-cost cross-border mobile money services. A key attribute to cross-border mobile money providers is the existence of mature domestic mobile money services. Efforts should be taken in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu to strengthen the already operational domestic services.

In countries where fintech-based remittance services are available, a high share of the population is covered by network signal. However, this does not always translate into good network performance. GSMA’s Mobile Connectivity Index rates the network performance of the Solomon Islands and PNG in 2017 as the worst in the Pacific and among the worst in the world.7 In Vanuatu, almost a quarter of Ni-Vanuatu users complained about network reliability in the Financial Demand Side Surveys. These countries need to prioritise the development of ICT infrastructure in the ICT sector, possibly through public-private partnerships. In 2018, Samoa saw the arrival of an undersea cable system, which brought more affordable and reliable international connectivity to the country. PNG lags in terms of mobile phone and fixed broadband subscriptions. In 2017, only 11.2% of the population used the internet, the lowest in the region, according to the World Development Indicators.8 Moreover, only 54% of the population had access to electricity. Electrification is essential for mobile, digital and ICT technology.9

In terms of improving accessibility, PNG has put forward a bill for a blockchain-focused Special Economic Zone. In 2018, the National Institute of Digital Currency Research was established in Vanuatu with the objective of studying the application of blockchain technology. Vodafone Fiji’s Innovation Lab has been operating since 2017 with the support of the Pacific Financial Inclusion Programme with the aim of leveraging digital platforms.

Another important aspect for regulators is the implementation of consumer protection frameworks. Consumer protection to prevent fraudulent, misleading and unfair commercial practices are needed that equally safeguards data privacy and security. Consumers should have the right to dispute any unauthorised transaction. A key obstacle for Pacific islanders to using financial services is the lack of official documentation needed to open accounts. For example, workers in the rural or informal sector are less likely to have wage slips or proof of domicile and might lack documentation to open an account. Regulators should establish appropriate account opening and documentation requirements to avoid financially excluding legitimate consumers and businesses.

In terms of increasing awareness, in Samoa, regional awareness of fintech-based remittance services, in particular of mobile money, is still low. Alternative advertising, such as ‘below-the-line’ marketing, has in the past resulted in higher registration and customer activity rates (GSMA, 2014).10 In PNG, the mobile money provider Nationwide advertised by sending representatives to villages and plantations to promote their product and using ‘ambassadors’ (active mobile money users from Port Moresby) to promote mobile money.

In terms of literacy, financial education campaigns are a great way to promote fintech-based remittance services and product understanding. This should be considered by Tonga, one of the few countries that has not put this initiative into practice. Financial education campaigns could be introduced in schools to promote digital financial services. In addition, financial education for seasonal workers specifically aimed at fintech services for remittances should be considered. Also important are financial literacy classes for adults, tailored for migrant workers and their communities.

In Fiji, about 63% of mobile money users live in urban areas, as revealed by the Financial Demand Side Surveys; but rural households are as likely to receive remittances as urban ones. Efforts should be made to reach the more isolated parts of the country where most of the unbanked individuals live and where a cash culture is more deeply rooted. Among rural respondents, 54% do not have a bank account compared to 26% in urban areas. One strategy could be to target important industries in rural areas in Fiji and promote fintech adoption in related activities. A good example of such projects was the one led by the Australian Government, Pacific Financial Inclusion Programme and ANZ Bank in 2016 in the Solomon Islands. The main purpose was to encourage the application of digital banking services in the coconut industry, a sector chosen because most workers lived in rural areas (distant from traditional banking services) and because of its economic relevance (United Nations Development Programme, 2016).

Finally, it is important to highlight the need for data collection for future policy action. The Pacific suffers from a lack of relevant and reliable data, which makes it harder for policymakers to take informed decisions. The research scope of this article is challenged by data scarcity at the time of writing. Nauru, for instance, does not report the volume of remittances received. In Palau, data on the level of ICT development is non-existent. Recent efforts to provide information on the transaction costs of remitting money to the Pacific, as well as data on fintech companies operating in the region are notable. But several countries are still lacking data, namely Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru and Palau. Furthermore, household survey data regarding financial inclusion and connectivity is scarce and outdated. The Financial Services Demand Side Surveys were only conducted in Fiji, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu, leaving more than half of the Pacific SIDS not surveyed.

7 CONCLUSION

Pacific SIDS have large influxes of cross-border remittances, but the transaction costs of sending money to the region are among the highest in the world. Among the causes for costly remittances are geographical isolation, remoteness, small populations and severe infrastructure gaps. Given the great number of households that rely on these flows, measures must be taken to address this issue.

To overcome these challenges, fintech companies are emerging as viable alternatives to traditional RSPs. Fintech companies are cheaper but not as yet as widely used as traditional RSPs. Unlike banks or MTOs, which need adequate physical infrastructure to operate, fintech makes greater use of technology, and depends less on the conventional distribution channels. A greater variety of remittance service providers is also expected to put downward pressure on the fees of traditional money transfer providers.

The ladder methodology constitutes a useful tool for the analysis of the fintech landscape and sets the stages for policy action. If policymakers wish to promote fintech, several rungs have to be climbed, as conceptualised in the ladder framework: availability, accessibility, awareness, literacy and trust. The Pacific region still faces many challenges regarding fintech adoption. Some countries such as Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Palau and Tuvalu require the development of basic digital infrastructure to encourage the availability of fintech services. The more pressing issue for countries such as PNG, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu is the degree of accessibility to fintech services. For more advanced countries in terms of fintech adoption, for example Samoa and Tonga, policy emphasis should be geared towards awareness and financial education. In countries where fintech is even more firmly established, as in Fiji, the focus should be on promoting trust by ensuring inclusivity for rural and more isolated regions.

The level of public support needed to develop the digital infrastructure required to increase the availability and accessibility of fintech in many Pacific SIDS is a necessary condition. Developing its digital infrastructure will not only serve to facilitate fintech services but also a variety of development needs. Digital technology acts as an enabler and accelerator of achieving the SDGs. This is especially relevant for Pacific SIDS that rely heavily on service sector generated growth.

This article examined the status of fintech in the Pacific to supplement traditional RSPs by providing cheaper and quicker remittances to the Pacific. Given the large volume of remittances that is transferred to the Pacific from its overseas workers, savings resulting from reduced remittance costs would be recycled into the local economy and spur greater growth. However, for the majority of Pacific SIDS, developing basic digital infrastructure remains the first hurdle and high priority. For countries with established infrastructure, awareness remains the major stumbling block to the widespread adoption of fintech services. Greater focus on financial and technological literacy is required, with a focus on the use and benefits of fintech application. For the one or two countries with established infrastructure and greater financial awareness, building trust in the fintech systems through targeted promotion (for example for rural users) should be explored to broaden the use of fintech platforms throughout the country.

Fintech provides an opportunity for Pacific SIDS to leapfrog and accelerate the financial inclusion of yet underbanked and unbanked communities. It can promote the further acceleration of the economic pillar of the SDGs by promoting financial inclusion and financial deepening. The role of government to build baseline infrastructure and to work in partnership with the private sector to raise awareness and build trust in fintech remains a challenge. While the challenges are big for the Pacific, the rewards will be equally big if not greater.

Biographies

Dr Hongjoo Hahm is former Deputy Executive Secretary of United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP).

Dr Tientip Subhanij is Chief of Investment and Enterprise Development at UNESCAP.

Rui Almeida is former consultant at UNESCAP.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1 Data was accessed from World Development Indicators (WDI) in November 2019.

- 2 The Financial Services Demand Side Surveys were led by national central banks in cooperation with the Pacific Financial Inclusion Program (Central Bank of Samoa, 2015; Central Bank of Solomon Islands, 2015; National Reserve Bank of Tonga, 2016; Pacific Financial Inclusion Programme, 2016; Reserve Bank of Fiji, 2015; Reserve Bank of Vanuatu, 2016).

- 3 In 2017–2018, the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) in Australia granted 8459 visas to Pacific islanders, whereas New Zealand’s Recognised Seasonal Employers (RSE) program welcomed 9673 people; migrants are predominantly from Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu (Department of Home Affairs, 2019; Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment, 2019).

- 4 Western Union, for instance, is a money transfer operator which provides both online and over-the-counter remittance services; because it is not exclusively operating digitally, it is not considered an online platform.

- 5 SendMoneyPacific is a government-backed initiative that aims to provide information on the costs of sending money overseas to Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu from Australia, New Zealand or the United States.

- 6 These figures are based on our analysis of the Remittance Prices Worldwide database: https://remittanceprices.worldbank.org/en.

- 7 See GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index, www.mobileconnectivityindex.com/#year=2017.

- 8 See World Bank, Individuals using the Internet (% of population) – Papua New Guinea, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=PG.

- 9 See World Bank, Access to electricity (% of population), https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.ZS?end=2017&locations=PG&start=1996.

- 10 Below-the-line advertising is a strategy that avoids mainstream media, such as radio or television, and prefers to target consumers directly.