Emergency department activities at the Athletes' Village during the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games

Abstract

Aim

More than 15,000 elite athletes participated in the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Providing adequate medical services to these elite athletes was a priority. Hence, a polyclinic was established in the Athletes' Village. Visitors were triaged at the emergency department of the polyclinic to enable early treatment of critical illnesses or injuries in the emergency room (ER) and to identify patients suspected of having coronavirus disease as early as possible. No reports of emergency department activities at large sporting events in the pandemic era are available. Here, we aim to summarize the activities at the emergency department of the polyclinic.

Methods

Data were collected using an electronic medical record system, nursing records, and questionnaires administered during triage from July 13 to September 8, 2021. Polyclinic data involving accredited athletes and team members were summarized.

Results

During the Olympic Games, 12,318 triage cases were reported, of which 75 were treated in the ER. During the Paralympic Games, 8398 triage cases were reported, of which 94 were treated in the ER. During the Olympic Games, musculoskeletal issues (26 patients) were the most common. During the Paralympic Games, ear, nose, and throat issues were the most common (21 patients). Two patients experienced cardiopulmonary arrest in the Athletes' Village and were transported to the hospital postresuscitation.

Conclusion

During the study period, many critically ill patients were triaged and treated at the emergency department. Our data can be used to improve medical care and infection prevention at future international sporting events.

INTRODUCTION

The Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games (Tokyo 2020 Games) were postponed to 2021 due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Therefore, making the Tokyo 2020 Games a successful event while protecting the health and safety of the athletes and public was an unprecedented project.1-3

At the Tokyo Olympic Games, 11,417 athletes participated, representing 206 National Olympic Committees (NOCs). Meanwhile, at the Tokyo Paralympic Games, 4403 athletes participated, representing 162 National Paralympic Committees (NPCs). The Tokyo 2020 Games were held under a “closed bubble system” that severely restricted the movement of athletes and staff to prevent the spread of COVID-19.4-6 A polyclinic constructed in the Athletes' Village provided specialized sports medicine services to athletes and team members from the NOCs and NPCs, focusing on athletes. This polyclinic included emergency, orthopedic, internal medicine, women's health, dentistry, ophthalmology, dermatology, psychiatry, outpatient fever treatment, and urology departments. Moreover, necessary medical care up to primary emergency care was also provided at the polyclinic (Figure 1A).7, 8 The polyclinic could not perform hospitalizations or surgeries; therefore, when hospitalization or advanced medical care was needed, the athletes were transferred to medical facilities outside the Athletes' Village in cooperation with the designated hospitals for the Games. The same service was provided at the Paralympic Games. The clinics were open 16 h a day, from 07:00 to 23:00 h, while the emergency department was open 24 h a day, from July 13 to September 8, 2021. The emergency departments performed triage at the polyclinic entrance and managed the emergency room (ER; Figure 1B). Emergency department staff conducted triage to provide early treatment to critically ill or injured patients and to identify patients suspected of having COVID-19 as early as possible.

Some reports have summarized patient management at the polyclinic emergency department during previous Olympic Games9-11; however, no reports have summarized the management of patients at Paralympic Games. Furthermore, we believe there are no reports of triage being performed at Olympic and Paralympic Games polyclinics. Because the abovementioned reports were generated during the Olympic Games in the prepandemic era, we aimed to summarize the activities at the emergency department of the polyclinic in the Athletes' Village during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The polyclinic was established in the Multi-Function Complex (MFC) at the center of the Harumi Athletes' Village. An outpatient fever clinic was set up in a temporary medical facility opposite the MFC. The clinic provided emergency medicine, orthopedics, internal medicine, women's health, dentistry, ophthalmology, dermatology, psychiatry, outpatient fever treatment, physiotherapy, clinical laboratory tests, and imaging; moreover, pharmaceutical departments were established during the Olympic and Paralympic Games period. Notably, urology services were established only during the Paralympic Games period. Patients from the Athletes' Village visiting for initial and repeat consultations, examination only, or physical therapy only, as well as patients who were transferred from the stadium and their attendants, were checked in the triage department for antecedent states and suspected infections (Figure 1C).

To identify patients suspected of having COVID-19 or other infectious diseases at an early stage and prevent nosocomial infections, triage was carried out using thermometers and medical questionnaires. Patients with symptoms of an infectious disease at the time of triage were instructed to visit the outpatient fever clinic directly. Triage was performed mainly by the emergency department doctors and nurses. Patients with unstable vital signs, anticipated need for transfer, severe symptoms, or diseases requiring emergency treatment, including head trauma, were moved directly from the triage site to the emergency department.

At the polyclinic, information on all athletes and NOC staff treated for injuries and illnesses was entered into an electronic medical record form (client-side module of General Electric Athlete Management Solution; GE AMS) (General Electric Company). Data were collected using an electronic medical record system (GE AMS),1 nursing records on paper, and questionnaires administered during triage (Figure 1D). During triage, the following data were collected: date and time of triage, athlete/nonathlete status, presence of fever, which NOC or NPC they belonged to, and the purpose of their visit. These data were temporarily recorded on paper and later transferred to Excel (Microsoft). Data were analyzed retrospectively. Data analysis and figure creation were performed using Microsoft 365 version 2303 (Microsoft). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. We only used percentages to represent descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Triage

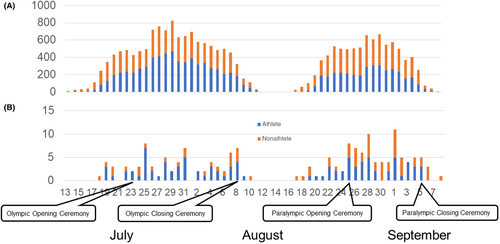

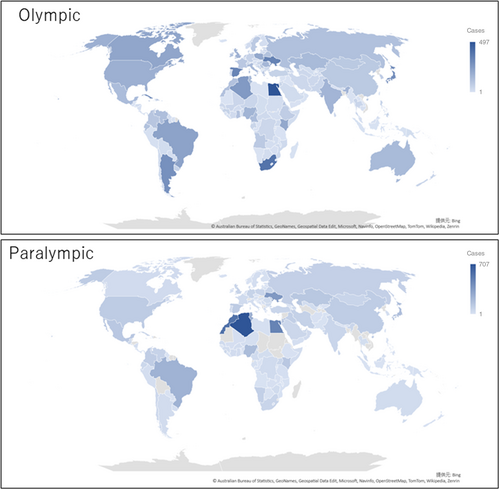

During the Olympic Games, 12,318 triage cases were reported, of which 6444 (52.3%) involved athletes. During the Paralympic Games, 8398 triage cases were reported, of which 3623 (42.9%) involved athletes. During the Paralympic Games, more than half of the visits were by nonathletes (e.g., chaperones of athletes or team members; Figure 2A). The most common reason for visits to the polyclinic was medical treatment for both the Olympic (4678 cases) and Paralympic (3700 cases) Games. The second most common and remaining reasons differed between the Olympic and Paralympic Games (Table 1). In the Paralympic Games, the second most common reason for these visits was team members visiting the clinic to accompany the patients (1755 cases). All treatments at the polyclinic, except for emergency services, required online booking appointments. Due to the difficulty of the online booking process, 671 cases during the Olympic Games and 624 cases during the Paralympic Games visited the clinic only to book an appointment for a future visit. The frequency of visitors to the polyclinic during the Olympic and Paralympic Games is presented by country and region of affiliation in a world map in Figure 3. Overall, 10 (0.08%) and 16 (0.19%) patients were transferred from the triage site to the fever outpatient clinic during the Olympic and Paralympic Games, respectively. Moreover, 75 and 94 emergency department visits were observed during the Olympic and Paralympic Games, respectively.

| Olympics (n = 12,318) | Paralympics (n = 8398) | |

|---|---|---|

| Medical treatment | 4678 (38) | 3700 (44) |

| Physical therapy only | 1.528 (12) | 777 (9) |

| Accompanying patients | 1484 (12) | 1755 (21) |

| Reservation only | 671 (5) | 624 (7) |

| Tour of the clinic | 422 (3) | 299 (4) |

| Prescription only | 198 (2) | 117 (1) |

| Imaging test only | 155 (1) | 65 (1) |

| Other | 1198 (10) | 248 (3) |

| Unknown | 1984 (16) | 813 (10) |

- Note: Data are shown as n (%).

Emergency room

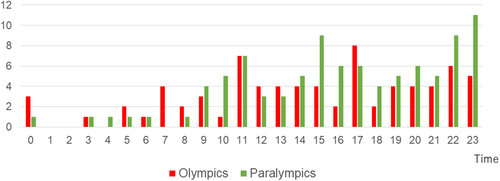

The number of patients in the emergency department stratified by disease is presented in Table 2. Of the 75 cases (mean 2.5 cases per day) reported during the Olympic Games, 51 (68%) involved athletes; of the 94 cases (mean 4.1 cases per day) reported during the Paralympic Games, 47 (50%) involved athletes. Emergency departments treated the most patients on July 25 during the Olympic Games (8 patients) and on September 1 (11 patients) during the Paralympic Games (Figure 2B). The greatest number of patients were treated by the emergency department in the 17:00 time slot during the Olympic Games (8 patients) and in the 23:00 time slot during the Paralympic Games (11 patients; Figure 4). During the Olympic Games, musculoskeletal issues (26 patients) were the most common, followed by gastrointestinal disorders including abdominal pain (13 patients). During the Paralympic Games, ear, nose, and throat issues were the most common (21 patients), followed by musculoskeletal (19 patients) issues. Cases of diseases necessitating emergency transport to an external hospital, examination, and monitoring were considered serious. The most serious cases were gastrointestinal issues during the Olympic Games and dermatological issues during the Paralympic Games. Two cases of cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) occurred in the Athletes' Village; both the patients were quickly resuscitated by cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) using an automated external defibrillator (AED). One patient was transported directly from the scene of occurrence to the hospital, whereas the other patient was transported to the hospital after waiting in the ER. In addition to emergency care, the emergency department also treated patients who could not be treated by the established departments. From the polyclinic, 29 external medical transfers during the Olympic Games and 17 external transfers during the Paralympic Games were reported. From the emergency department, eight external transfers during the Olympic Games and five during the Paralympic Games were reported.

| Category | Olympics | Paralympics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (75) | Serious cases (16) | Total (94) | Serious cases (19) | |||

| Musculoskeletal | 26 | Facial trauma | 3 | 19 | Facial trauma | 1 |

| Muscle contusion | 1 | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | 13 | Esophageal stricture | 1 | 12 | Stomach ache | 2 |

| Appendicitis | 1 | Pancreatitis | 1 | |||

| Stomach ache | 2 | |||||

| Diarrhea | 1 | |||||

| Ear, nose, and throat | 11 | Eardrum injury | 2 | 21 | 0 | |

| Neurological | 10 | Consciousness disorder | 1 | 13 | Convulsions | 2 |

| Dermatological | 3 | 0 | 12 | Toe necrosis | 1 | |

| Cellulitis | 6 | |||||

| Cardiovascular | 3 | Chest pain | 1 | 8 | Cardiopulmonary arrest | 2 |

| Dyspnea | 1 | |||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | |||||

| Allergy, asthma | 2 | Anaphylaxis | 1 | 3 | Anaphylaxis | 1 |

| Asthma | 1 | |||||

| Urology | 2 | 0 | 6 | Urinary tract infection | 1 | |

| Dental | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Heatstroke and dehydration | 2 | Heatstroke | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ophthalmic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

DISCUSSION

Triage

The present study reported the activities of the emergency department during the Tokyo 2020 Games, conducted during the COVID-19 epidemic. Triage can help identify diseases at their initial presentation. Triage was performed by the emergency department to screen and isolate patients with COVID-19, thereby avoiding its transmission to other patients in the polyclinic. Athletes and team members from the NOCs and NPCs who tested positive for COVID-19 during airport quarantine or daily polymerase chain reaction screening testing visited the fever outpatient clinic directly without visiting the polyclinic. The number of athletes suspected of being infected based on clinical symptoms at triage was 0.08% at the Olympic Games and 0.19% at the Paralympic Games. These patients were directly transferred to the fever outpatient clinic. Moreover, the number of patients visiting the hospital varied by region (Figure 2). Although the size of the Paralympic team was only 1/3 the size of the Olympic team, the number of patients visiting the polyclinic was comparable to that during the Olympic Games. The Paralympic athletes who visited the polyclinic were often accompanied by staff members.

Emergency room patients

The emergency department was busy after the opening ceremony and before and after the closing ceremony of both the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Thus, it may be important for future Games to have more staff available during these periods. Furthermore, patients often came to the emergency department late in the evening. This might have been influenced by the fact that competition finals were scheduled at night.

During the Olympic Games, the largest number of patients had musculoskeletal issues, including cuts and lacerations, followed by digestive system issues, including abdominal pain, while during the Paralympic Games, the largest number of patients had otorhinolaryngological issues, followed by musculoskeletal and gastrointestinal issues. An otolaryngology department was not established at the polyclinic during the Tokyo 2020 Games, and patients with otorhinolaryngological issues were planned to be transferred to the designated hospitals for the Games. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, these hospitals could not receive all patients with otorhinolaryngological issues, and many patients were treated in the emergency department. During the Olympic Games, some patients were transferred to hospitals because of eardrum damage, but most other patients required the removal of earwax and treatment of complaints including earache. In future Games, the polyclinic should have an otolaryngology department.

Severity

Patients with severe trauma were transported directly from the competition venues to hospitals. Another clinic was established at a venue located away from Tokyo.12 Therefore, not all patients were assessed at the polyclinic. For urgent cases needing surgery or hospitalization, an ambulance was dispatched to the hospital for emergency transportation. If a patient needed to be assessed by a department not located in the hospital or needed tests that could not be performed in the hospital (e.g., computed tomography scan), an ambulance was arranged to transport the patient to the receiving hospital, accompanied by a staff member of the organizing committee. During the Paralympic Games, two cases of CPA were observed: one in an athlete and the other in a nonathlete. In the first case, the patient collapsed outdoors in the Athletes' Village. The team doctor determined that the patient was in CPA and initiated CPR. Local staff ran to the polyclinic for help; thereafter, ER doctors and nurses rushed to the site with a first-aid bag and an AED, and defibrillation was performed. After defibrillation, the patient was resuscitated and their consciousness and vital signs were stabilized. According to the patient and team doctor, they had not been previously diagnosed with a heart disease. The patient was transported by ambulance to a hospital. In the second case, the patient experienced loss of consciousness indoors. A doctor on site determined that the patient was in CPA and initiated CPR with the use of an AED. Another doctor ran to the polyclinic for assistance. When the polyclinic physician arrived on scene, the patient was resuscitated and regained consciousness. Afterwards, the patient was carried by stretcher to the polyclinic. Their vital signs were stable at the scene of the CPA and upon arrival at the polyclinic. According to the patient and the team doctor, they had angina pectoris. An electrocardiogram and echocardiogram were performed at the polyclinic; however, no abnormal findings were found. The patient was then transported by ambulance from the polyclinic to an outside hospital.

Heatstroke

As high temperatures and humidity were predicted for the Tokyo Olympic Games, measures were taken to prevent heatstroke. Educational materials on heat acclimatization were prepared for athletes and widely distributed to them to help them prepare for the Games. It was also anticipated that patients with heatstroke would visit the polyclinic. Therefore, various heatstroke countermeasures were implemented, including replenish fluids, chilled intravenous fluids, air conditioning, fans, ice packs, misting, and ice baths. However, only two cases of heatstroke were managed by the emergency department. Inoue et al. reported that the incidence of heatstroke at each of the competition venues was also less than what had been expected.13, 14 The low incidence of heatstroke could have been due to adequate prevention and proper treatment.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, only a small number of selected patients were treated in the polyclinic. This study is not representative of the total population of medical cases managed during the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Severely injured patients were transported from the venue directly to hospitals, bypassing the polyclinic emergency area, and these patients' data were not included in the study. Second, some triage data were not recorded when the polyclinic was crowded. However, there have been no studies to date that detail polyclinic visits during large sporting events. Third, the definition of serious injury or illness could have differed among the staff conducting triage. Thus, collection of more detailed triage data from the polyclinic at the Athletes' Village could facilitate the smooth operation of medical facilities at large-scale competitions.

CONCLUSION

The emergency department responded appropriately, appropriate triage was performed, and no COVID-19 clusters were noted at the Athletes' Village clinic during the Tokyo 2020 Games, which was initially a concern due to the ongoing pandemic. Our data can be used to improve medical care and infection prevention at future international sporting events.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the medical staff who worked at the Tokyo 2020 Games polyclinic. We would also like to thank the staff of the cooperating hospitals who accepted our transfers despite the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the staff at the metropolitan hospital who sent us to the Athletes' Village clinic, even though the hospital was very busy due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, which had no role in the execution of this study or the interpretation of the results.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing interests for this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol: We treated all information with strict confidentiality and de-identified our medical database after the Games. The requirement for informed consent was waived as all data in our epidemiological study were anonymized and de-identified. Approval was obtained from Ethics Committee of Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital for the use of these data for publication (no. 03-120). Permission to conduct this study and for the use of medical data from the Tokyo 2020 Games was obtained from the Tokyo 2020 Organising Committee.

Informed consent: N/A.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.