Performance of Universal TOR rule for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study

Abstract

Aim

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a public health problem. The Universal Termination of Resuscitation (TOR) rule attempts to reduce the rate of futile transports. The aim of this study was to examine and compare the performance of the TOR rule for OHCA cases in Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, where the TOR rule has not been implemented.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study examined data from January 1, 2009, to June 30, 2018, reported to the Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study. We included patients with nontraumatic OHCA in the four countries and compared the performance of the Universal TOR rule in these countries.

Results

The number of eligible cases was 173,629. The performance of the Universal TOR rule for cases of neurologically poor survival showed a positive predictive value of more than 0.99 in all four countries. However, specificity differed among them: Japan 0.938, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.931–0.945; Korea 0.922, 95% CI: 0.901–0.939; Singapore 0.985, 95% CI: 0.964–0.993; and Taiwan 0.773, 95% CI: 0.736–0.807.

Conclusion

The positive predictive value of neurologically poor survival in cases meeting the Universal TOR rule among the four countries was greater than 99%. However, the specificity of these cases that met the Universal TOR rule differed among the four countries. Therefore, further refinement of the Universal TOR rule may be needed for local implementation. The quality of resuscitation in an out-of-hospital setting may also impact survival and neurological outcomes and needs to be considered in any implementation of TOR.

INTRODUCTION

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a public health problem worldwide. The Universal Termination of Resuscitation (TOR) rule was developed to reduce the proportion of futile patient transports in systems that routinely transport all OHCA cases to the hospital, including those that fail to achieve return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after life support delivered by emergency medical services (EMS) providers in an out-of-hospital setting.1 The TOR rule was developed to improve the allocation of medical resources and safety by reducing unnecessary consumption of medical resources, hazards faced by EMS providers, and risks to EMS providers and the public associated with high-speed transport.1, 2 The American Heart Association (AHA) and European Resuscitation Council (ERC) cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) guidelines include TOR rules for OHCA cases to be implemented in different local settings and healthcare systems.1, 3-5 The Universal TOR rule is more sensitive than and superior to the Advanced Life Support (ALS) TOR rule.6, 7 The Universal TOR rule states that resuscitation can be discontinued in an out-of-hospital setting by EMS if the following three criteria are met: (1) The cardiac arrest was not witnessed by EMS providers; (2) the patient did not obtain ROSC despite attempted resuscitation; and (3) no shocks were delivered in an out-of-hospital setting (i.e., not a shockable rhythm) at any time prior to transport.5

In Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, EMS providers were historically not permitted to terminate resuscitation in an out-of-hospital setting during the research period of this study.8-10

In this study, we used data from the Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS) to simulate the outcomes of patients with OHCA in Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, in which the TOR rule has not yet been introduced. The aim of this study was to examine the performance of the TOR rule and compare it in the PAROS countries.

METHODS

Study design, setting, and population

This study was a retrospective cohort study examining data from January 1, 2009, to June 30, 2018, reported to PAROS. We used data from OHCA cases from Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan that were enrolled in PAROS. The PAROS data did not cover the entire population of the countries involved (Singapore excluded). Of these, we included cases of nontraumatic adult OHCA and excluded those cases not transported by EMS and those for whom resuscitation was not performed or it was unclear whether resuscitation was performed. We defined a case of OHCA as a person who was unresponsive, not breathing, and without a pulse outside the hospital setting.

The PAROS network and selection of participants

Recognizing the need for a collaborative research group for prehospital emergency care in Asia, researchers in the Asia-Pacific region established the PAROS Clinical Research network in 2010. The mission of the PAROS network is to “promote high-quality research on resuscitation to improve outcomes from prehospital and emergency care.” The diversity of participating countries provides insight into the differences among prehospital emergency care systems in Asia and allows for the identification of strategies that impact OHCA outcomes.11

The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University (approval no.: 2017118). The requirement for individual informed consent was waived per the Personal Information Protection by Law and National Research Ethics Guideline in Japan and the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University.

Data collection

The PAROS network has developed a standard data collection form and taxonomy for OHCA cases that span dispatch, EMS, emergency department, and in-hospital outcomes. The records were reviewed by facility principal investigators, dispatchers, and study coordinators. These records were then verified by study coordinators in the trial coordinating center. Detailed descriptions of the data collection method can be found in a paper previously published by the PAROS network.12

EMS in Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan

Among EMS personnel in Japan, specially trained emergency care providers known as emergency life-saving technicians (ELSTs) are authorized to use automated external defibrillators, perform advanced airway procedures using supra-glottic airways (SGAs), and administer fluids to cases with OHCA. With support and direction from online medical control, specially trained ELSTs are also permitted to perform other advanced care, including administering adrenaline and performing endotracheal intubation (ETI) in patients with OHCA.

CPR procedures approved for South Korean EMS providers include chest compressions, use of an automated external defibrillator, and ETI. Intravenous epinephrine during CPR is administered under medical guidance.

Singapore's EMS providers are equipped with Basic Life Support skills that include defibrillation using an automated external defibrillator (AED). They can also provide ALS using SGAs, manual defibrillation, mechanical CPR, and administration of drugs such as adrenaline and amiodarone.

In Taiwan, most EMS providers are trained to perform basic life support, intravenous access, and laryngeal mask airway insertion, but they cannot administer intravenous medications. However, some cities have paramedics who are allowed to perform ALS procedures, including intravenous drug administration.

In all four countries, EMS providers are historically not permitted to terminate resuscitation in an out-of-hospital setting, and all patients who have resuscitation attempted must be transported to the hospital. Resuscitation is not attempted if there are obvious signs of death (e.g., decapitation, lividity, or rigor mortis).

Outcomes

Neurological outcomes were assessed using the cerebral performance category (CPC) scale: Category 1, good cerebral performance; Category 2, moderate cerebral disability; Category 3, severe cerebral disability; Category 4, coma or vegetative state; and Category 5, death. The primary outcome measure was neurologically favorable survival on discharge or one-month survival, defined as CPC Category 1 or 2. The secondary outcome was survival to discharge.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are summarized as numbers and proportions, whereas continuous variables are summarized as mean and standard deviation. We examined the number of cases with CPC 1 or 2 and one-month survival and compared those that met the Universal TOR rule with those that did not in the four countries. For comparisons among the four countries, categorical variables were subjected to the χ2 test and continuous variables to one-way ANOVA. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We examined the positive predictive value (PPV) and specificity to compare the performance of the Universal TOR rule in the four countries. Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical package version 26.0J (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

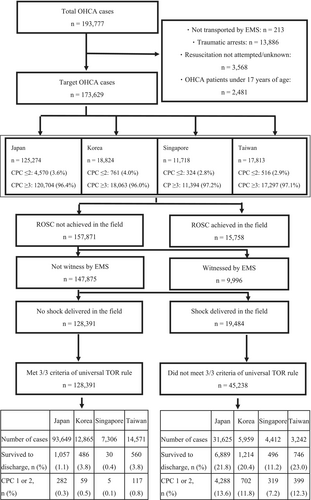

During the study period, 193,777 OHCA cases were enrolled in the PAROS dataset, of which 173,629 were nontraumatic adult target OHCA cases. Among these 173,629 cases, the number of target OHCA cases and the proportion of cases with neurologically favorable survival in each country were as follows: Japan: n = 125,274, CPC ≤2 n = 4570 (3.6%); Korea: n = 18,824, CPC ≤2 n = 761 (4.0%); Singapore: n = 11,718, CPC ≤2 n = 324 (2.8%); and Taiwan: n = 17,813, CPC ≤2 n = 516 (2.9%) (Figure 1).

The background of the included OHCA cases and details of EMS management were as follows. The mean age was highest in Japan (74.3 ± 15.7 years). OHCA witnessed by bystanders tended to be highest in Singapore (52.0%: 6089/11,718 cases). Bystander CPR was lowest in Taiwan (31.2%: 5558/17,813 cases), and Singapore had the highest rate of performed ALS care (epinephrine administration: 54.6%, 6396/11,718 cases; implementation of advanced airway management: 87.6%, 10,260/11,718 cases). Survival outcomes of target cases, including survival to discharge or one-month survival, in each country were as follows: Japan: n = 7946/125,274 cases (6.3%), Korea: n = 1700/18,824 cases (9.0%), Singapore: n = 526/11,718 cases (4.5%), and Taiwan: n = 1306/17,813 cases (7.3%). If the Universal TOR rule were applied correctly, the transport rates for each country would have been as follows: Japan 25.2%, Korea 31.7%, Singapore 37.7%, and Taiwan 18.2% (Table 1).

| Japan | Korea | Singapore | Taiwan | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 125,274 | 18,824 | 11,718 | 17,813 | – |

| Age (y. o.), mean ± SD | 74.3 ± 15.7 | 66.1 ± 16.5 | 67.1 ± 16.0 | 70.9 ± 16.8 | <0.01 |

| Male, n (%) | 71,506 (57.1) | 12,171 (64.7) | 7564 (64.6) | 11,577 (65.0) | <0.01 |

| Cardiogenic cardiac arrest, n (%) | 81,287 (64.9) | 14,637 (77.8) | 8471 (72.3) | 14,996 (84.2) | <0.01 |

| Witnessed by bystander, n (%) | 43,287 (34.6) | 7612 (40.4) | 6089 (52.0) | 6262 (35.2) | <0.01 |

| Witnessed by EMS providers, n (%) | 9095 (7.2) | 1245 (6.6) | 934 (8.0) | 938 (5.3) | <0.01 |

| Bystander CPR, n (%) | 52,552 (41.9) | 8358 (44.4) | 5216 (44.5) | 5558 (31.2) | <0.01 |

| First arrest rhythm | |||||

| Shockable rhythm, n (%) | 9383 (7.5) | 3136 (16.7) | 2144 (18.3) | 1652 (9.3) | <0.01 |

| Asystole, n (%) | 70,825 (56.5) | 11,370 (60.4) | 5795 (49.5) | 7876 (44.2) | <0.01 |

| PEA, n (%) | 24,287 (19.4) | 2629 (14.0) | 3266 (27.9) | 2818 (15.8) | <0.01 |

| Unknown unshockable rhythm, n (%) | 17,258 (13.8) | 808 (4.3) | 467 (4.0) | 1873 (10.5) | <0.01 |

| Unknown, n (%) | 3521 (2.8) | 881 (4.7) | 46 (0.4) | 3594 (20.2) | <0.01 |

| AED implementation by citizens, n (%) | 1232 (1.0) | 433 (2.3) | 357 (3.0) | NA | <0.01 |

| Prehospital defibrillation, n (%) | 16,270 (13.0) | 4408 (23.4) | 3127 (26.7) | 1759 (9.9) | <0.01 |

| Response time (min), median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | 6.0 (4.0–7.0) | 8.7 (6.7–11.3) | 6.0 (4.7–8.0) | <0.01 |

| Epinephrine administration, n (%) | 13,384 (10.7) | NA | 6396 (54.6) | 1839 (10.3) | <0.01 |

| Implementation of advanced airway management, n (%) | 48,418 (38.6) | 3881 (20.6) | 10,260 (87.6) | 12,305 (69.1) | <0.01 |

| Outcome | |||||

| Prehospital ROSC, n (%) | 12,712 (10.1) | 1124 (6.0) | 943 (8.0) | 979 (5.5) | <0.01 |

| Survived to discharge, n (%) | 7946 (6.3) | 1700 (9.0) | 526 (4.5) | 1306 (7.3) | <0.01 |

| Post-arrest CPC 1/2, n (%) | 4570 (3.6) | 761 (4.0) | 324 (2.8) | 516 (2.9) | <0.01 |

| TOR rule (test positive), n (%) | 93,649 (74.8) | 12,865 (68.3) | 7306 (62.3) | 14,571 (81.8) | <0.01 |

| Predicted transport rate of OHCA cases (if TOR rule implemented), (%) | 25.2 | 31.7 | 37.7 | 18.2 | – |

- Note: Categorical variables are summarized as numbers and proportion, whereas continuous variables are summarized as means and standard deviations. For comparisons among the four countries, categorical variables were subjected to the χ2-test and continuous variables to one-way ANOVA. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

- Abbreviations: AED, automated external defibrillator; CPC, cerebral performance category; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMS, emergency medical services; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; TOR, termination of resuscitation.

We examined in greater detail the 128,391 OHCA cases that met the Universal TOR rule for termination. The proportion of OHCA cases with neurologically favorable survival was less than 1% in each country (Figure 1, Table S1). There were 45,238 OHCA cases that did not meet the Universal TOR rule, and neurologically favorable survival was around 10% in each country (Figure 1, Table S2).

The performance of Universal TOR rules across the four countries was as follows. For neurologically poor survival of OHCA cases, the PPV was greater than 0.99 in each country. However, there were differences in specificity (Japan 0.938, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.931–0.945; Korea 0.922, 95% CI: 0.901–0.939; Singapore 0.985, 95% CI: 0.964–0.993; and Taiwan 0.773, 95% CI: 0.736–0.807) (Table 2, Table S3).

| Death within one month | CPC ≥3 of OHCA cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

| All four countries (95% CI) | 0.779 (0.778–0.779) | 0.814 (0.807–0.821) | 0.983 (0.983–0.984) | 0.207 (0.205–0.208) | 0.764 (0.764–0.764) | 0.925 (0.918–0.931) | 0.996 (0.996–0.997) | 0.126 (0.125–0.127) |

| Japan (95% CI) | 0.789 (0.789–0.790) | 0.867 (0.860–0.874) | 0.989 (0.988–0.989) | 0.218 (0.216–0.220) | 0.774 (0.773–0.774) | 0.938 (0.931–0.945) | 0.997 (0.997–0.997) | 0.136 (0.135–0.137) |

| Korea (95% CI) | 0.723 (0.721–0.725) | 0.714 (0.693–0.734) | 0.962 (0.959–0.965) | 0.204 (0.198–0.209) | 0.709 (0.708–0.710) | 0.922 (0.901–0.939) | 0.995 (0.994–0.996) | 0.118 (0.115–0.120) |

| Singapore (95% CI) | 0.650 (0.649–0.651) | 0.943 (0.920–0.960) | 0.996 (0.994–0.997) | 0.112 (0.110–0.114) | 0.641 (0.640–0.641) | 0.985 (0.964–0.993) | 0.999 (0.998–1.000) | 0.072 (0.071–0.073) |

| Taiwan (95% CI) | 0.849 (0.847–0.851) | 0.571 (0.546–0.596) | 0.962 (0.959–0.964) | 0.230 (0.220–0.240) | 0.836 (0.835–0.837) | 0.773 (0.736–0.807) | 0.992 (0.991–0.993) | 0.123 (0.117–0.128) |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CPC, cerebral performance category; NPV, negative predictive value; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PPV, positive predictive value.

DISCUSSION

This study used PAROS data to examine the outcomes of nontraumatic adult OHCA cases by applying the 2006 Universal TOR rule to the OHCA cases during the study period in the four Asian EMS systems of Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. The PPV for neurologically poor survival exceeded 99% based on the 2006 TOR rule criteria. The results of the survey indicate that the introduction of the Universal TOR rule has the potential to be effective in the Asian region.

The PPV of the Universal TOR rule for cases with neurologically poor survival (CPC ≧ 3) following OHCA was greater than 0.99, thus demonstrating a neurologically favorable survival of less than 1% with narrow CIs when the TOR rule was applied in all four countries. The 1% cutoff value was the most commonly referenced standard of futility and used during the development of the TOR rules and referenced in the guidelines.4 However, the PPV of the Universal TOR rule for cases with death within one month following OHCA was less than 99%. Therefore, in this study, it should be noted that there are ethical concerns that can arise from considering neurological prognosis as a criterion.

However, there was a clinically important variation in the specificity of the Universal TOR rule for cases with neurologically poor survival following OHCA, which indicates a wide range in the proportion of survivors who met the TOR rule in an out-of-hospital setting. In this study, specificity ranged from 77.3% to 98.5% (Table 2), and the results were inconsistent, showing wide CIs. In countries with low specificity of the Universal TOR rule, this might indicate that the Universal TOR rule possibly includes potential survivors with a good neurological prognosis. The extremely low proportion of OHCA cases in which bystander CPR was performed in Taiwan compared to the other three countries may have influenced the low specificity for cases with neurologically poor survival. In Singapore, a series of community and prehospital interventions were implemented from 2011 to 2016 to improve OHCA survival rates under a national strategic five-year plan, and efforts were made to improve the rate of bystander CPR. The focus on community and EMS training (particularly dispatchers) was particularly effective.13 As such, it is thought that the rate of bystander CPR implementation differs depending on the efforts in each country. Our results show that if the Universal TOR rule were applied correctly, predicted transport rates could decrease to 18.2–37.7% (Japan 25.2%; Korea 31.7%; Singapore 37.7%; and Taiwan 18.2%) (Table 1). Comparing these results to a previous local study (with a predicted transport rate of 35.6%), the Universal TOR rule resulted in a lower transport rate for OHCA patients.14

Specificity for death within one month in this study was also low, ranging from 57.1% to 94.3% (Table 2). In their meta-analyses, Nas et al.15 pointed out the low specificity for death in hospital or at 30 days in non-Western regions, particularly in Asia. TOR rules are legally recognized in several regions of Europe and the United States, with about 60% of OHCA patients in Europe and 55% in the United States being transported to the hospital, compared to almost all OHCA patients (96%) in Asia.16, 17 In areas where the TOR rule has been implemented, discontinuation of CPR is permitted if the patient does not have ROSC after more than 20 min of continuous CPR.18 In Asian countries, EMS often follows a scoop-and-run strategy and has shorter CPR times in an out-of-hospital setting.19 Therefore, the TOR rule may be applied more quickly if it is implemented in Asia because the time spent on the scene by EMS is generally shorter in Asian cities than in Europe and the United States. Grunau et al. suggested that the diagnostic accuracy of the TOR rule increases as the time to TOR rule application is extended,20 and early application of the TOR rule may result in an undesirable recommendation of termination.

In their meta-analyses, Nas et al.15 also showed that studies with a lower proportion of patients with attempted defibrillation in an out-of-hospital setting had lower specificity. The underlying etiology might also differ between Europe, the United States, and Asian countries, with a higher rate of shockable rhythms in Europe and the United States. In the present study, it is difficult to say if the proportion of patients with attempted defibrillation in an out-of-hospital setting had an effect on specificity.

Although the TOR rule is now currently in place in Singapore,21 many Asian countries have yet to adopt prehospital TOR rules for a variety of reasons, which include differences in sociocultural backgrounds regarding death and legal barriers.2 The “rescue culture” mindset and the perception that death is an unsuccessful outcome in many prehospital EMS interactions also limit the widespread adoption of TOR protocols.22 Studies carried out in various parts of the United States found a disparity in the perceptions of members of the public and family members to termination of resuscitation.23-25 This is also true of the Asian region, suggesting that such perceptions are unique to each local community. Focus group discussions with relevant local emergency care stakeholders would be useful to better understand the feasibility of introducing TOR rules in each local community.14

Kajino et al.26 validated a TOR rule to predict poor neurological outcome in a Japanese population and concluded that more specific TOR rules for each region could be developed. Our results suggest that introducing the same TOR rules to regions with different EMS organizations, treatment protocols, laws, and religious beliefs may be problematic and that the original North American TOR rules need to be refined to the local situation.

Limitations

First, as the field TOR rules have not yet been adopted in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and only very recently in Singapore, this study could only evaluate the performance of the universal TOR rule. Also, as this study was an analysis of past data, the situation could be quite different in these countries now. Further, the PAROS data did not cover the entire population of the countries involved (Singapore excluded). Second, the relevance of our results is still unclear because of different emergency medical protocols and differences in the epidemiology of OHCA in the four countries. Third, the duration of resuscitation at the scene by the EMS providers is not known, and longer transport times imply longer CPR time in the ambulance during transport. Because of the lack of data on the quality of CPR during transport in this study, we were unable to perform any analysis on this factor. Finally, resuscitation guidelines indicate that therapeutic temperature management, extracorporeal CPR, and percutaneous coronary intervention improve neurological outcomes. In the absence of such data, we were unable to analyze these confounding factors in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

We used PAROS data to examine the association between the Universal TOR rule and outcomes of patients with OHCA in Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, in which the TOR rule has not yet been implemented during the study period. The PPV for neurologically poor survival in cases that met the Universal TOR rule was greater than 99%, but there were differences in specificity among the four countries. As medical care is evolving, TOR rules also need to evolve in response to the context of the emergency medical care situation, which varies from region to region. Therefore, it is necessary to develop TOR rules for each region, based on customization of the original TOR rules, to suit the local medical situation and other factors. Furthermore, when the TOR rules are introduced in Asian countries, studies are needed to evaluate the impact of the introduction of the TOR rules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study Clinical Research Network.

Participating Site Investigators: P Khruekarnchana (Rajavithi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand), NE Doctor (Sengkang General Hospital, Singapore), LP Tham (KK Women's & Children's Hospital, Singapore), MYC Chia (Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore), HN Gan (Changi General Hospital, Singapore), Leong BSH (National University Hospital, Singapore), Mao DRH (Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore), R Rao (GVK Emergency Management and Research Institute, Telangana, India), M Vimal (GVK Emergency Management and Research Institute, Telangana, India), B Velasco (East Avenue Medical Center, Manila, Philippines), Zhou SA (Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital, Zhejiang, China), N Khan (Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan), Nguyen DA (Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam), Ng YY (Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore), A Shalini (Singapore Civil Defence Force, Singapore).

We would like to thank Ms. Pek Pin Pin, Ms. Nur Shahidah, and the late Ms. Susan Yap from the Health Services and Systems Research, Duke-NUS Medical School and Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, for coordination of the study. We would also like to thank Ms. Patricia Tay from the Singapore Clinical Research Institute for her role as secretariat for the PAROS network.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

MEH Ong reports funding from the Zoll Medical Corporation for a study involving mechanical CPR devices; grants from the Laerdal Foundation, Laerdal Medical, and Ramsey Social Justice Foundation for funding of the Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study; an advisory relationship with Global Healthcare SG, a commercial entity that manufactures cooling devices; and funding from Laerdal Medical on an observation program to their Community CPR Training Centre Research Program in Norway. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Dr. Yasuyuki Kuwagata is an Editorial Board member of the Acute Medicine & Surgery journal and a coauthor of this article. To minimize bias, he was excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol: The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University (approval no.: 2017118).

Informed consent: The requirement for individual informed consent was waived per the Personal Information Protection Law and National Research Ethics Guidelines in Japan and the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Study variables, data dictionary, collection form, and protocol will be shared at the study trial coordinating center's webpage: https://www.scri.edu.sg/crn/pan-asian-resuscitation-outcomes-study-paros-clinical-research-network-crn/about-paros/. The data that support the findings of this study are available from PAROS, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. To request data from this study, please contact the corresponding author.