Factors influencing the delivery of automated external defibrillators by lay rescuers to the scene of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in schools

Abstract

Aim

Timely use of automated external defibrillators by lay rescuers significantly improves the chances of survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest cases. We aimed to identify the factors influencing whether lay rescuers bring automated external defibrillators to the scene of nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in schoolchildren in Japan.

Methods

Data on out-of-hospital cardiac arrests among schoolchildren from April 2008 to December 2021 were obtained from the database of the Stop and Prevent cardIac aRrest, Injury, and Trauma in Schools study. A multivariate Modified Poisson regression analysis was performed to evaluate the factors influencing whether a lay rescuer brought an automated external defibrillator to the scene of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and the year-by-year changes in automated external defibrillator delivery for each factor were assessed.

Results

Of the 333 nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrests across the entire study period, lay rescuers brought automated external defibrillators in 85.3% of cases. Female patients and incidents occurring during non-sports activities had lower proportions of automated external defibrillator delivery. Significant year-by-year improvements in automated external defibrillator delivery were observed, with the overall proportion increasing from 73.7% in 2008–2010 to 93.3% in 2020–2021. However, the trend was less pronounced for female students, non-sports activities, and incidents occurring in classrooms/other locations than their counterparts.

Conclusions

AED delivery to the scene of OHCA in schools has improved overall, with the proportion increasing from 73.7% in 2008–2010 to 93.3% in 2020–2021. However, there is still room for improvement, particularly in female patients, and incidents during non-sports activities.

INTRODUCTION

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) requires immediate intervention to prevent fatal outcomes and is a leading cause of death in many industrialized countries, including Japan.1-3 Timely use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) by lay rescuers significantly improves the chances of survival in OHCA cases.4, 5 The Japan Resuscitation Council Resuscitation Guidelines 2020 emphasize that when cardiac arrest is suspected, AEDs should be promptly delivered to the scene without hesitation.6

Schools are unique environments for AED implementation owing to the high concentration of children and adolescents. Although pediatric OHCA represents a small subset of overall OHCA incidents,7-9 it has a significant societal impact in terms of lost productive years, healthcare costs for survivors, and emotional burden for families.7 Despite the increasing use of AEDs by lay rescuers for OHCA of schoolchildren in recent years, there remain some cases in which AEDs are not utilized.10, 11 This highlights the need for continued efforts to improve accessibility and usage of AEDs in school settings.

To ensure that AEDs are delivered more frequently to the OHCA scene in schools, identifying and addressing the factors associated with lay rescuers' AED use is essential. Understanding these factors can inform targeted educational programs and policies for enhancing emergency preparedness in schools. Therefore, this study aimed to identify the factors influencing whether lay rescuers bring AEDs to the scene of nontraumatic OHCAs among schoolchildren in Japan. Specifically, it aimed to explore the time trends in AED delivery by lay rescuers for various factors, identifying which factors showed improvement over time and which did not.

METHODS

Study design

This study was conducted as part of the Stop and Prevent cardIac aRrest, Injury, and Trauma in Schools (SPIRITS) study. The rationale, design, and profile of SPIRITS have been previously described in detail.12 Briefly, the SPIRITS study integrates data from two large-scale registries: the Injury and Accident Mutual Aid Benefit System of the Japan Sport Council (JSC) and All-Japan Utstein Registry of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA). The JSC database includes records of injuries, illnesses, and accidents occurring under school supervision,13 whereas the FDMA registry documents OHCAs based on the international Utstein format.14, 15 Therefore, SPIRITS covers a comprehensive range of OHCA incidents among Japanese schoolchildren and provides a robust database for analysis.

Data collection

Data on OHCAs among schoolchildren throughout Japan between April 1, 2008 and December 31, 2021, were obtained from the SPIRITS database. The primary outcome measure was whether lay rescuers brought the AED to the OHCA scene. We did not consider whether the AED pad was actually attached or defibrillated. Secondary outcomes included ventricular fibrillation (VF) as the first documented rhythm and 1-month survival with favorable neurological outcome, defined as the Glasgow-Pittsburg cerebral performance category 1 or 2. Other variables included educational stage, sex, witness status of arrest, origin of arrest, activity at the time of arrest, location of arrest, first documented rhythm, and time of arrest.

Study population

This study included cases of nontraumatic OHCA of schoolchildren from elementary school (age 6–12 years), junior high school (age 12–15 years), high school (age ≥ 15 years), and technical college (age ≥ 15 years). The inclusion criteria were cases where resuscitation was attempted by emergency medical service (EMS) personnel or lay rescuers and the first documented rhythm was recorded. The exclusion criteria were OHCAs due to traumatic causes, arrests occurring outside the school premises, and cases that occurred after the arrival of EMS personnel.

Statistical analyses

A multivariate modified Poisson regression analysis was performed to evaluate the factors influencing lay rescuers' AED delivery to the OHCA scene to estimate risk ratios (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The analysis included potential factors for lay rescuers' AED delivery, such as sex (male or female), educational level (elementary school, junior high school, or high school/technical college), witness of arrest (witnessed or not witnessed), origin of arrest (cardiac or noncardiac), activity at the time of arrest (sports classes, sports club activities, or non-sports activities), location of arrest (athletic field, gymnasium, swimming pool, classroom/others), and time of arrest (weekdays from 8:00 to 16:00 or all other times, including weekends). Furthermore, Cochran–Armitage tests for trends were applied to assess year-by-year changes in AED delivery for each factor. In addition, the associations between lay rescuers' AED delivery and the secondary outcomes, including VF as the first documented rhythm and 1-month survival with favorable neurological outcome, were evaluated for each factor using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 J (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Study population

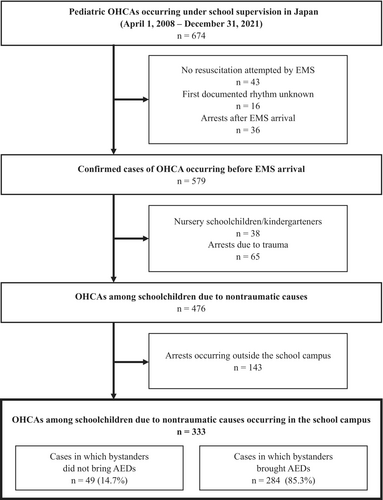

Figure 1 illustrates the selection process for the study participants. Between April 2008 and December 2021, 476 nontraumatic OHCAs cases among schoolchildren were identified. Of them, 333 cases that occurred on school campuses were included in the analysis. Of the 333 OHCAs cases across the entire study period, lay rescuers brought an AED to the scene in 284 (85.3%) cases. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population. The study population comprised 249 (74.8%) male patients. Most OHCAs were witnessed by lay rescuers (294 [88.3%] cases) and were of cardiac origin (297 [89.2%] cases). OHCAs occurred most frequently during physical activity, with 116 (34.8%) cases occurring during sports classes and 149 (44.7%) cases during sports club activities. Most OHCAs occurred in facilities related to physical activity, with 159 (47.7%) in athletic fields, 80 (24.0%) in gymnasiums, and 32 (9.6%) in swimming pools.

| Total | Bringing AEDs to the scene of OHCA by bystanders | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | (%) | RR | (95% CI) | p-value | RR | (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|

Sex |

Male | 249 | 224 | (90.0%) | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Female | 84 | 60 | (71.4%) | 0.794 | (0.689–0.915) | 0.001 | 0.849 | (0.738–0.977) | 0.022 | |

|

Educational stage |

Elementary school | 67 | 47 | (70.1%) | 0.790 | (0.669–0.932) | 0.005 | 0.839 | (0.700–1.004) | 0.056 |

| Junior high school | 105 | 94 | (89.5%) | 1.008 | (0.925–1.098) | 0.856 | 0.995 | (0.916–1.080) | 0.898 | |

| High school/technical college | 161 | 143 | (88.8%) | Reference | Reference | |||||

|

Witness of arrest |

Witnessed | 294 | 255 | (86.7%) | 1.166 | (0.965–1.410) | 0.112 | 1.062 | (0.869–1.296) | 0.558 |

| Not witnessed | 39 | 29 | (74.4%) | Reference | Reference | |||||

|

Origin of arrest |

Cardiac | 297 | 254 | (85.5%) | 1.026 | (0.880–1.196) | 0.740 | 0.860 | (0.721–1.026) | 0.095 |

| Noncardiac | 36 | 30 | (83.3%) | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Activity at the time of arrest | Sports classes | 127 | 116 | (91.3%) | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Sports club activities | 138 | 118 | (85.5%) | 0.936 | (0.858–1.021) | 0.138 | 0.927 | (0.834–1.030) | 0.160 | |

| Non-sports activities | 68 | 50 | (73.5%) | 0.805 | (0.691–0.937) | 0.005 | 0.764 | (0.587–0.996) | 0.046 | |

| Location of arrest | Athletic field | 159 | 139 | (87.4%) | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Gymnasium | 80 | 72 | (90.0%) | 1.029 | (0.937–1.131) | 0.544 | 1.031 | (0.945–1.125) | 0.488 | |

| Swimming pool | 32 | 25 | (78.1%) | 0.894 | (0.737–1.083) | 0.253 | 0.927 | (0.761–1.129) | 0.450 | |

| Classroom/other places | 62 | 48 | (77.4%) | 0.886 | (0.765–1.026) | 0.105 | 1.065 | (0.833–1.361) | 0.614 | |

| Time of arrest | Weekdays from 8:00 to 16:00 | 232 | 199 | (85.8%) | 1.019 | (0.923–1.126) | 0.708 | 1.074 | (0.956–1.205) | 0.229 |

| All other times, including weekends | 101 | 85 | (84.2%) | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Total | 333 | 284 | (85.3%) | |||||||

- Abbreviations: AED, automated external defibrillator; CI, confidence interval; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; RR, risk ratio.

Factors of AED delivery by lay rescuers

Table 1 also shows the proportion of lay rescuers bringing AEDs to the OHCA scene for each potential factor and the results of the modified Poisson regression analyses across the entire study period. The multivariate analysis revealed that female patients had a lower likelihood of AED delivery than male patients (RR, 0.849; 95% CI, 0.738–0.977). Similarly, cases occurring during non-sports activities were less likely to receive AED intervention compared with those occurring during sports classes (RR, 0.764; 95% CI, 0.587–0.996).

Year-by-year trends of AED delivery by lay rescuers

Table 2 shows the year-by-year trend in the proportion of lay rescuer AED delivery from 2008 to 2021 according to each subgroup. Overall, the proportion of AED deliveries by lay rescuers significantly increased over the study period, from 73.7% in 2008–2010 to 93.3% in 2020–2021 (p < 0.001). A significant improvement in the proportion of AED deliveries was also observed between 2008 and 2021 in most subgroups. Nevertheless, the improvements were less pronounced for female students (p = 0.113), non-sports activities (p = 0.343), and cases occurring in classrooms/other locations (p = 0.872) than their counterparts.

| Year | P-for-trend | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2010 | 2011–2013 | 2014–2016 | 2017–2019 | 2020–2021 | |||

| Sex | Male | 84.0% | 81.4% | 93.2% | 96.7% | 100.0% | 0.001 |

| Female | 53.8% | 81.8% | 77.8% | 77.8% | 77.8% | 0.113 | |

| Educational stage | Elementary school | 37.5% | 66.7% | 80.0% | 94.4% | 80.0% | 0.001 |

| Junior high school | 80.0% | 92.0% | 95.2% | 88.5% | 100.0% | 0.168 | |

| High school/technical college | 85.7% | 81.6% | 91.9% | 94.1% | 94.1% | 0.100 | |

|

Witness of arrest |

Witnessed | 76.5% | 84.3% | 91.9% | 92.6% | 92.3% | 0.003 |

| Not witnessed | 50.0% | 63.6% | 83.3% | 90.0% | 100.0% | 0.015 | |

|

Origin of arrest |

Cardiac | 74.3% | 81.2% | 91.7% | 92.9% | 92.9% | <0.001 |

| Noncardiac | 66.7% | 83.3% | 87.5% | 87.5% | 100.0% | 0.245 | |

|

Activity at the time of arrest |

Sports classes | 74.1% | 93.9% | 90.5% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.001 |

| Sports club activities | 77.4% | 75.9% | 94.4% | 87.1% | 100.0% | 0.027 | |

| Non-sports activities | 66.7% | 68.4% | 81.8% | 84.6% | 71.4% | 0.343 | |

| Location of arrest | Athletic field | 69.7% | 90.9% | 88.9% | 94.3% | 100.0% | 0.003 |

| Gymnasium | 81.3% | 78.6% | 95.0% | 95.2% | 100.0% | 0.036 | |

| Swimming pool | 60.0% | 57.1% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.012 | |

| Classroom/other places | 82.4% | 68.8% | 87.5% | 76.9% | 75.0% | 0.872 | |

| Time of arrest | Weekdays from 8:00 to 16:00 | 70.2% | 83.9% | 92.3% | 96.7% | 90.0% | <0.001 |

| All other times, including weekends | 84.2% | 76.0% | 89.7% | 77.8% | 100.0% | 0.371 | |

| Total | 73.7% | 81.5% | 91.2% | 92.3% | 93.3% | <0.001 | |

Outcomes after OHCA according to lay rescuer AED delivery to the scene

Table 3 shows the outcomes after OHCA based on whether lay rescuers brought AEDs to the scene. Overall, VF as the first documented rhythm was observed in 82.0% of cases where an AED was brought, compared to 49.0% when an AED was not brought (p < 0.001). One-month survival with favorable neurological outcome was 55.6% in the AED group, compared to 24.5% in the non-AED group (p < 0.001). In most subgroups, cases where an AED was brought to the scene showed better outcomes, with a higher proportion of VF and improved 1-month survival with favorable neurological outcome, compared to cases where an AED was not brought.

| Bringing AEDs to the scene of OHCA by bystanders | Total | VF | CPC 1 or 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | (%) | p-value | n | (%) | p-value | |||

|

Sex |

Male |

Yes | 224 | 188 | (83.9%) |

<0.001 |

129 | (57.6%) |

0.005 |

| No | 25 | 13 | (52.0%) | 7 | (28.0%) | ||||

|

Female |

Yes | 60 | 45 | (75.0%) |

0.010 |

29 | (48.3%) |

0.020 |

|

| No | 24 | 11 | (45.8%) | 5 | (20.8%) | ||||

|

Educational stage |

Elementary school |

Yes | 47 | 25 | (53.2%) |

0.173 |

19 | (40.4%) |

0.043 |

| No | 20 | 7 | (35.0%) | 3 | (15.0%) | ||||

|

Junior high school |

Yes | 94 | 82 | (87.2%) |

0.005 |

56 | (59.6%) |

0.369 |

|

| No | 11 | 6 | (54.5%) | 5 | (45.5%) | ||||

|

High school/technical college |

Yes | 143 | 126 | (88.1%) |

0.002 |

83 | (58.0%) |

0.004 |

|

| No | 18 | 11 | (61.1%) | 4 | (22.2%) | ||||

|

Witness of arrest |

Witnessed |

Yes | 255 | 215 | (84.3%) |

<0.001 |

145 | (56.9%) |

<0.001 |

| No | 39 | 20 | (51.3%) | 11 | (28.2%) | ||||

|

Not witnessed |

Yes | 29 | 18 | (62.1%) |

0.225 |

13 | (44.8%) |

0.048 |

|

| No | 10 | 4 | (40.0%) | 1 | (10.0%) | ||||

|

Origin of arrest |

Cardiac |

Yes | 254 | 229 | (90.2%) |

<0.001 |

156 | (61.4%) |

<0.001 |

| No | 43 | 23 | (53.5%) | 11 | (25.6%) | ||||

|

Noncardiac |

Yes | 30 | 4 | (13.3%) |

0.829 |

2 | (6.7%) |

0.418 |

|

| No | 6 | 1 | (16.7%) | 1 | (16.7%) | ||||

|

Activity at the time of arrest |

Sports classes |

Yes | 116 | 106 | (91.4%) |

0.005 |

86 | (74.1%) |

0.452 |

| No | 11 | 7 | (63.6%) | 7 | (63.6%) | ||||

|

Sports club activities |

Yes | 118 | 106 | (89.8%) |

<0.001 |

67 | (56.8%) |

<0.001 |

|

| No | 20 | 12 | (60.0%) | 3 | (15.0%) | ||||

|

Non-sports activities |

Yes | 50 | 21 | (42.0%) |

0.287 |

5 | (10.0%) |

0.894 |

|

| No | 18 | 5 | (27.8%) | 2 | (11.1%) | ||||

|

Location of arrest |

Athletic field |

Yes | 139 | 127 | (91.4%) |

<0.001 |

87 | (62.6%) |

0.001 |

| No | 20 | 13 | (65.0%) | 5 | (25.0%) | ||||

|

Gymnasium |

Yes | 72 | 63 | (87.5%) |

0.006 |

44 | (61.1%) |

0.543 |

|

| No | 8 | 4 | (50.0%) | 4 | (50.0%) | ||||

|

Swimming pool |

Yes | 25 | 22 | (88.0%) |

0.286 |

20 | (80.0%) |

0.053 |

|

| No | 7 | 5 | (71.4%) | 3 | (42.9%) | ||||

|

Classroom/other places |

Yes | 48 | 21 | (43.8%) |

0.045 |

7 | (14.6%) |

0.129 |

|

| No | 14 | 2 | (14.3%) | 0 | (0.0%) | ||||

|

Time of arrest |

Weekdays from 8:00 to 16:00 |

Yes | 199 | 155 | (77.9%) |

<0.001 |

111 | (55.8%) |

0.002 |

| No | 33 | 15 | (45.5%) | 9 | (27.3%) | ||||

|

All other times, including weekends |

Yes | 85 | 78 | (91.8%) |

<0.001 |

47 | (55.3%) |

0.007 |

|

| No | 16 | 9 | (56.3%) | 3 | (18.8%) | ||||

| Total | Yes | 284 | 233 | (82.0%) |

<0.001 |

158 | (55.6%) |

<0.001 |

|

| No | 49 | 24 | (49.0%) | 12 | (24.5%) | ||||

- Abbreviations: AED, automated external defibrillator; CPC, cerebral performance category; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the factors influencing whether lay rescuers bring AEDs to the scene of nontraumatic OHCAs among schoolchildren in Japan and investigated the 14-year trends in AED delivery. A unique feature of this study is its focus on whether lay rescuers brought an AED to the scene, rather than whether the AED was actually used. This approach provides a clear measure of lay rescuer intervention and highlights the crucial first step in the chain of survival by ensuring that an AED is promptly available at the scene. Previous studies have mostly concentrated on AED use and effectiveness,4, 5 but the actual usage of AEDs depends on the specific circumstances and conditions of the patient. By focusing on the act of bringing the AED, this study highlights a key aspect of lay rescuer response that is essential for improving overall emergency preparedness and outcomes. The insights gained from this research can guide improvements in emergency response protocols and lay rescuer education within school environments, supporting broader efforts in acute medicine to optimize prehospital care and enhance the effectiveness of early interventions in critical situations. Additionally, these findings could serve as valuable evidence for consideration in future updates to resuscitation guidelines, particularly in emphasizing the role of AED availability and timely intervention in prehospital settings. Our findings will inform targeted interventions and strategies to enhance AED accessibility and usage in school settings, ultimately improving survival outcomes in schoolchildren experiencing OHCA.

Our results indicate a significant year-by-year improvement in the proportion of AED deliveries by lay rescuers. This remarkable progress indicates the successful implementation of AED and resuscitation education programs in Japanese schools. Several factors contribute to this positive trend. First, the widespread distribution of AEDs in schools has likely played a significant role. In 2017, almost all public elementary, junior high, and high schools in Japan had at least one AED installed.16 Second, many teachers, staff members, and students have been equipped with the knowledge and skills to respond effectively to cardiac emergencies. As of 2017, approximately 95% of schools in Japan have conducted basic life support (BLS) training sessions for some or all staff members, and 74% have held training sessions for all staff members annually.16 BLS training for students has been provided during health and physical education classes, as stipulated by the curriculum guidelines for junior high17 and high schools.18 The proportions of schools providing hands-on training in health and physical education classes were as follows: 11.4% in elementary schools, 58.9%, junior high schools; and 66.0%, high schools. Third, the dissemination of the “ASUKA Model19” in schools across Japan has likely contributed to this positive trend. The ASUKA Model19 was developed in 2012 as a guideline for accident response in schools in response to a fatal accident that occurred at an elementary school in Saitama Prefecture in 2011. Schools nationwide have been implementing this model to enhance their emergency preparedness and response capabilities. Continued efforts to enhance these initiatives can serve as a model for other public places and contribute to further improvements in emergency response and survival rates for OHCAs.

This study also revealed that female students with OHCAs had a lower likelihood of receiving AED interventions than male students. Moreover, the improvement in AED delivery over time was less pronounced in females than in males, with no significant trend observed. Such sex disparities in lay rescuer interventions have been noted in various studies over the years.20-23 The persistent sex disparity despite the overall improvements in AED delivery suggests that deeply ingrained social and psychological factors influence lay rescuer behavior.24 A previous questionnaire survey indicated that female respondents feared inappropriate contact, whereas male respondents feared accusations of sexual assault or harassment,25 both of which would be factors that inhibited the administration of lay rescuer interventions for women. Targeted interventions are essential to address these disparities. Educational campaigns should emphasize that legal protections for lay rescuers who provide emergency assistance apply equally, regardless of the patient's sex. Furthermore, training programs should include scenarios involving female patients to help normalize AED use in these situations. Featuring female rescuers and patients in training videos and campaigns can normalize AED use for women, reducing sex biases.

We also found that the proportion of AED deliveries was lower during non-sports activities compared with OHCAs occurring during sports classes. Additionally, the improvement in AED delivery over time was less pronounced in non-sports settings. One reason for this disparity can be the strategic placement of AEDs, predominantly near areas where physical activities are conducted. The most common locations for AED placement in schools were staff/visitor entrances and gymnasiums.16 Considering that most schools in Japan have only one or two AEDs,16 this placement strategy, while logical for high-risk sports events, may insufficiently cover all areas where OHCAs can occur. Furthermore, the visibility and perceived urgency of OHCAs during sports activities are relatively high, prompting a quicker and more decisive response from lay rescuers. Sports activities are often closely supervised, and the physical exertion involved increases the risk of cardiac events. By contrast, non-sports activities may not have the same level of supervision or immediate recognition of cardiac emergencies, leading to delayed responses. BLS training that simulates OHCAs in various locations can also improve lay rescuer readiness and response times, regardless of the activity or location. Enhancing awareness of the importance of AED accessibility in all areas of schools can help create a more comprehensive emergency preparedness strategy, ultimately improving the outcomes for all students. Furthermore, increasing education and training for students, who are often the bystanders present during emergencies, is also essential to improve overall emergency response readiness and outcomes in schools.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, a significant limitation is the lack of detailed information about lay rescuers. Our data did not include key characteristics or whether lay rescuers had received resuscitation training. The absence of detailed lay rescuer information limits the depth of analysis of the factors that influence AED delivery. Second, we did not consider the potential effects of individual school policies or emergency preparedness programs on AED delivery. Variations in training programs, AED accessibility, and school-specific response protocols can influence the likelihood of lay rescuer AED use. However, these factors were not measured or controlled for in this study. Third, as noted in a previous study,12 the SPIRITS database may underreport OHCA cases to some extent. This underreporting can be due to input errors in the data linkage items used to develop the database and because cases not transported to the hospital by EMS were not registered. Fourth, unmeasured and/or unknown factors might have influenced the proportion of lay rescuer AED deliveries. Further studies are required to identify and investigate additional factors that may affect AED delivery in school settings.

CONCLUSION

The present study investigated the factors affecting lay rescuer AED delivery in the context of nontraumatic OHCAs among schoolchildren in Japan. The proportion of AED deliveries by lay rescuers significantly increased from 73.7% in 2008–2010 to 93.3% in 2020–2021. However, there is still room for improvement, particularly in female patients and incidents during non-sports activities. Addressing these gaps requires further efforts to fulfill the stated aim of the AED Committee of the Japanese Circulation Society to achieve “zero sudden cardiac deaths in schools.”26

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the members of the FDMA and Injury and Accident Mutual Aid Benefit Department of the JSC for their contribution to data collection. We also thank our colleagues from the Osaka University Center of Medical Data Science and Advanced Clinical Epidemiology Investigator's Research Project for providing insight and expertise for our study. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language editing. This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (JP17K09132, JP20K10537, and JP24K13487).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Otsuma Women's University and Osaka University.

Informed consent: Personal identifiers were removed from the database, and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Registry and registration no. of the study/trial: This study was not registered.

Animal studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data not shared.