Sex-Based Disparities in Sinonasal Outcomes: A Population-Based Study

Funding: Dr Lee is supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Award Number K12AR084225.

Victoria S. Lee and Anthony I. Dick contributed equally to this work and are designated as first authors. Author order was determined in order of increasing seniority.

1 Introduction

Sinonasal inflammatory/infectious disorders, including allergic rhinitis (AR) or hay fever and sinus infections, pose a major health burden in the United States, with significant health and economic impacts [1]. Sex hormones have increasingly been shown to play a role in the immune system [2]. Evidence at the cellular level supports testosterone's and progesterone's immunosuppressive effects and estrogen's mixed pro- and anti-inflammatory effects [3, 4]. Epidemiological data show sex differences in immune-mediated diseases like asthma and atopic dermatitis, as adult females have higher prevalence rates, suggesting a hormonal influence [5].

Summary

- An association was observed between female sex and the sinonasal diseases/symptoms examined.

- Sinonasal disease/symptom prevalence exhibited a female predominance over the reproductive ages.

- The female predominance narrowed and/or reversed around the pubertal and menopausal transitions.

There is a paucity of epidemiologic literature on sex differences in AR, particularly in the United States [6]. A recent scoping review identified just seven studies with only one being a US population-based study, which found females were more likely to have AR [7, 8]. Similarly, the epidemiologic literature on other sinusitis besides chronic rhinosinusitis is limited and characterized by heterogeneous methodology and results and small sample sizes [8]. Using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, our study investigates sex-based differences in the prevalence of AR, sinus infections, and related symptoms, and across age groups.

2 Methods

NHANES assesses the health and nutritional status of a nationally representative sample of noninstitutionalized individuals aged 2 months and older in the United States [9]. The 2005–2006 cycle was used as it was the only one with detailed sinonasal disease and symptom data. The exposure variable was sex at birth, and the outcome variables were lifetime self-reported doctor diagnosis of hay fever, allergies, and sinus infection, as well as recent self-reported (past 12 months) hay fever episodes, allergy symptoms, and problems with sneezing. Covariates, including age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio (less than 1 means household income is below federal poverty level), interview language, health insurance coverage, smoking in home, and asthma history, were considered.

Descriptive statistics were calculated, and bivariate analyses performed using chi-square or t-test as appropriate, to compare sample characteristics between sexes. To evaluate the association of sex and each outcome, we conducted both bivariate analyses and multivariable logistic regression analyses. A forwards selection approach was used to determine the final multivariable model. Data were then grouped by age decade to calculate the proportions of participants by age decade and sex for each outcome. A p value of <0.05 denoted statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using statistical software R (version 4.2.3).

3 Results

Characteristics of the study sample and bivariate analyses between males and females are detailed in Table 1. In the bivariate analyses, females had significantly higher prevalence of all sinonasal outcomes than males.

| Variables |

Overall (n = 9264) |

Female (n = 4733) |

Male (n = 4531) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36 (18, 52) | 37 (19, 53) | 36 (18, 52) | 0.014* |

| Age decade | 0.2 | |||

| 1–10 | 2074 (12%) | 1043 (12%) | 1031 (13%) | |

| 10–20 | 2570 (15%) | 1293 (14%) | 1277 (16%) | |

| 20–30 | 1018 (14%) | 614 (14%) | 404 (14%) | |

| 30–40 | 818 (14%) | 426 (14%) | 392 (14%) | |

| 40–50 | 815 (16%) | 410 (16%) | 405 (16%) | |

| 50–60 | 630 (13%) | 313 (13%) | 317 (13%) | |

| 60–70 | 658 (8%) | 324 (8%) | 334 (8%) | |

| 70+ | 675 (8%) | 306 (8%) | 369 (7%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.11 | |||

| White | 3501 (68%) | 1756 (68%) | 1745 (69%) | |

| Mexican American | 2496 (10%) | 1295 (9%) | 1201 (10%) | |

| Other Hispanic | 310 (4%) | 165 (4%) | 145 (4%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2512 (12%) | 1260 (13%) | 1252 (12%) | |

| Multi-Racial/Other | 445 (6%) | 256 (6%) | 188 (5%) | |

| Family PIR | 3.0 (1.6, 4.8) | 2.9 (1.5, 4.7) | 3.1 (1.6, 4.9) | 0.010* |

| Language | 0.007* | |||

| English | 7949 (94%) | 4077 (95%) | 3872 (93%) | |

| Spanish | 1313 (6%) | 656 (6%) | 657 (7%) | |

|

Health insurance |

<0.001* | |||

| Yes | 7431 (83%) | 3859 (85%) | 3572 (81%) | |

| No | 1806 (17%) | 864 (15%) | 942 (19%) | |

| Smoking in home | 0.2 | |||

| Yes | 1637 (18%) | 794 (18%) | 843 (19%) | |

| No | 7540 (82%) | 3893 (82%) | 3647 (81%) | |

| Asthma history | 0.6 | |||

| Yes | 1318 (15%) | 655 (15%) | 663 (14%) | |

| No | 7928 (85%) | 4071 (85%) | 3857 (86%) | |

| Lifetime diagnosis of hay fever | 0.031* | |||

| Yes | 614 (10%) | 339 (12%) | 275 (9%) | |

| No | 8627 (90%) | 4382 (88%) | 4245 (91%) | |

| Lifetime diagnosis of allergies | <0.001* | |||

| Yes | 2480 (32%) | 1383 (37%) | 1097 (28%) | |

| No | 6751 (68%) | 3333 (63%) | 3418 (72%) | |

| Lifetime diagnosis of sinus infection | <0.001* | |||

| Yes | 1066 (15%) | 661 (19%) | 405 (11%) | |

| No | 8171 (85%) | 4057 (81%) | 4114 (89%) | |

| Recent hay fever episode |

0.014* |

|||

| Yes | 367 (6%) | 209 (7%) | 158 (5%) | |

| No | 8871 (94%) | 4509 (93%) | 4326 (95%) | |

| Recent allergy symptoms | <0.001* | |||

| Yes | 1643 (23%) | 931 (26%) | 712 (19%) | |

| No | 7580 (77%) | 3780 (74%) | 3800 (81%) | |

| Recent problems with sneezing | 0.025* | |||

| Yes | 2545 (33%) | 1314 (35%) | 1231 (32%) | |

| No | 6710 (67%) | 3414 (65%) | 3296 (68%) |

- Unweighted n is displayed in the top row.

- Weighted median/interquartile range for continuous variables and unweighted n/weighted column percentages for categorical variables are listed.

- Weighted values were used to calculate p values.

- Abbreviation: PIR, poverty income ratio.

- * p < 0.05 was considered significant.

In the multivariable analyses, females had increased odds of lifetime self-reported diagnosis of hay fever (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.06–1.65), allergies (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.40–1.80), and sinus infections (OR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.62–2.23). Females also had increased odds of self-reported recent hay fever episodes (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.17–2.14), allergy symptoms (OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.38–1.85), and sneezing (OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.01–1.29).

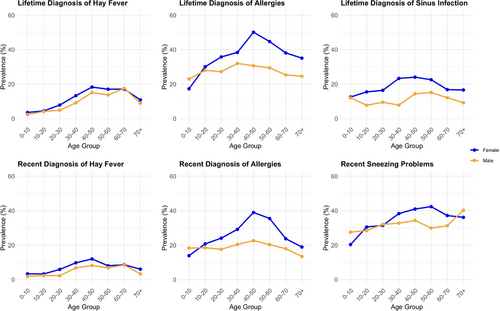

As demonstrated in Figure 1, sinonasal outcome prevalence varied by age. Except for hay fever, where female predominance persisted across all age groups, lifetime self-reported diagnosis of allergies and sneezing problems were less prevalent in females before the age of 10 years and became more prevalent afterward, peaking during the 40–50 years age group. For recent self-reported sinonasal outcomes, hay fever was more prevalent in women across all ages, while allergies and sneezing problems showed male predominance in the 1–10 years age group. Sneezing problems showed a male predominance in the 70+ years age group as well.

4 Discussion

This research, to our knowledge, constitutes the first population-based study examining the role of biological sex in sinonasal diseases/symptoms using the NHANES database. After controlling for sociodemographic and comorbid covariates in the 2005–2006 NHANES data, a significant association was observed between female sex and all the sinonasal diseases/symptoms examined. Our results align with findings from another US population-based study [8], adding to the relatively sparse existing literature suggesting a link between female sex and AR, as well as sinus infections. Our study is unique in that it is from a diverse, large dataset that is representative of the US population.

Additionally, we found that sex differences varied by age. In general, sinonasal disease/symptom prevalence exhibited a female predominance over the reproductive ages, with narrowing and/or reversals approximating the pubertal and menopausal transitions. These pattern changes at key sex hormone transition points are intriguing. A global meta-analysis investigating sex differences in the prevalence of rhinitis similarly reported a male predominance of rhinitis before puberty and a switch to a female predominance during and shortly after puberty, except in Asian populations [10]. In contrast to our study's findings, the observed sex differences did not persist into adulthood [10].

Collectively, the differences by biological sex overall and by age we found preliminarily suggest a role for sex hormones worthy of further investigation. Our study, however, has a few notable limitations. First, the outcome data were self-reported, which is subject to bias, and the analyses were limited by available data. Second, whether the statistically significant differences observed in our study are clinically meaningful requires future research with detailed sinonasal outcome data. Third, the cross-sectional study design only establishes association not causation. It is critical to investigate these relationships longitudinally in future research to establish causation and explore underlying mechanisms. Understanding the role of biological sex and sex hormones can inform clinical decision-making and treatment recommendations, with the potential to tailor them based on life stage.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.