The Decolonial Turn in Forensic Anthropology

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Forensic anthropology has matured into a formidable and fully fledged discipline that includes specialty graduate programs, diversified employment opportunities, an expanding scope, and improved regulation. As part of this maturity, and in step with other branches of science and the humanities, forensic anthropology has also experienced an upswing in discourse on decolonization and decoloniality. From its inception and throughout its history, anthropology has been a colonial venture that observes humans under a Western gaze. As a critique of the universality and superiority of Western systems of knowledge, the decolonial turn constitutes alternative ways of thinking and doing and provides space for these epistemes to circulate and thrive. In this synthesis, decolonization efforts within forensic anthropology are organized into five “C's” of appraisal: categories, casework, curricula, competence, and collections. Namely, these efforts feature the debates around sex, ancestry, and structural vulnerability estimation (categories); the expansion of humanitarian action and community involvement and the challenges to positivism, neutrality, and objectivity (casework); the assessment of how we educate, train, and value expertise (curricula and competence); and the interrogation of how we extract knowledge from the dead (collections). From the undercurrents of these five, a sixth C, care, is unveiled. Given the academic and practical value of forensic anthropology, especially vis-à-vis its consequences for colonized peoples, these discourses become imperative for the continued relevance of a colonialist field in a postcolonial world.

1 Introduction

Forensic anthropology is the applied arm of anthropological methods and theory to medicolegal issues. The specialty's primary purpose has been the analysis of unidentified human remains from criminal investigations, which has expanded to various contexts such as armed conflict, mass disasters, and migration. In the Boasian framework, forensic anthropology is borne out of (1) biological anthropology, which emphasizes knowledge of human physical variation and anatomy, and (2) archaeology, which provides skills in the systematic search, recovery, and spatiotemporal interpretation of sites and evidence; it is supported by cultural and linguistic anthropology, which evaluates the cultural context in which evidence is discovered or deaths occur. Common treatments of the history of forensic anthropology trace its academic roots back to 18th century centers of scholarship in Western Europe and the United States (Brickley and Ferllini 2007; Ubelaker 2020). Today, forensic anthropology represents a mature discipline with global applicability, boasting specialized graduate training programs, diverse employment opportunities, and professional certification. Unsurprisingly, a retrospective reflection of forensic anthropology's history has accompanied this maturity, opening discourse on anthropology's colonial legacies more broadly. This paper reviews recent efforts to decolonize forensic anthropology, recognizing the importance of such work to the continued growth of the field.

Decolonial theory predicates that European colonialism, beginning formally in the 15th century and continuing as settler colonial and neocolonial enterprises today, lays the foundation for many systems of inequality and is at the root of the current global apartheid. In its modern rendition, colonial ways of thinking and doing reveal themselves in themes of extraction, exploitation, subjugation, hegemony, and the like. Science is vulnerable to and indeed guilty of perpetuating these themes when actions and frames of reference are motivated by individualistic (Fitsch et al. 2020), transactional (Deloria Jr. 1988), exclusive (Reiter 2020), or opportunistic (Stefanoudis et al. 2021) designs. Decolonization then is the undoing of colonialism, colonial traditions, and colonial acts. Calls for decolonization signify both the literal return of land and resources to Indigenous hands (Tuck and Yang 2012) and the identification and reversal of oppressive systems (Mignolo 2011). For many who operate in this space, decolonization is an act of resistance that ultimately seeks to restore the agency of many across the world dehumanized by colonialism (Lugones 2017).

Because the prevailing construction of modern science is rooted in colonial endeavors of the Renaissance and the Age of Exploration and continues to grow under the stewardship of Western visionaries, virtually all branches of the academe can apply a decolonial lens to their fields. Ornithologists have identified a bias towards naming bird species found outside Europe after European persons (Trisos et al. 2021), while some botanists have problematized constitutions of native versus nonnative plants as (de)colonial (Mastnak et al. 2014). Meighan (2021) examines how the rules of English grammar and syntax can normalize certain racist or unjust worldviews. Even physics, often lauded as the most objective, purest, and hardest of the sciences, independent from social values, suffers in its analytical breadth, for example in the study of light, because of the exclusion of Indigenous perspectives (Salzmann et al. 2021). Indeed, decolonial epistemes abound in climate science (Whyte 2017), geoscience (Klymiuk 2021), geography (Shaw et al. 2006; Davis and Todd 2017), sociology (Connell 2018), mathematics (Iseke-Barnes 2000), education (Mbembe 2016), business management (Bruton et al. 2022), and political science (Shilliam 2021), among others.

Anthropology undeniably owes its existence to the West, which designated its agents as supreme scientific cataloguers of the Other. From its inception and throughout its history, anthropology has been a colonial venture that observes, describes, and analyzes humans under the Western gaze. Therefore, not only is it sensible for anthropology as a colonial architect to be its own dismantler, but it also is incumbent upon anthropologists to be active resisters. To decolonize anthropology means to (1) pinpoint how colonialism has shaped the field and reproduced power relations, especially in insidious ways; (2) challenge dominant assumptions, canon, or dogmata; and (3) accommodate alternative epistemes and ontologies such as Indigenous, feminist, queer, and Black theories and worldviews to stand on equal footing. Such reflections are not new for anthropology and abound across all its branches (e.g., Atalay 2006; Bolles 2023; Gupta and Stoolman 2022; Leonard 2021; Schroeder 2020).

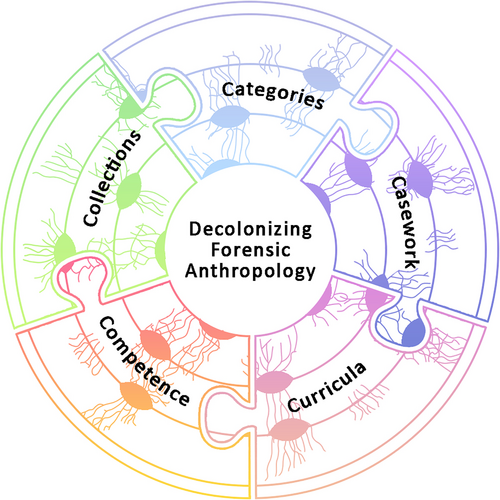

Forensic anthropology is experiencing its own decolonial turn. In this synthesis, I organize decolonization efforts within forensic anthropology into five “C's” of appraisal: categories, casework, curricula, competence, and collections (Figure 1). Namely, these efforts feature the debates around sex, ancestry, and structural vulnerability estimation (categories); the expansion of humanitarian action and community involvement and the challenges to positivism, neutrality, and objectivity (casework); the assessment of how we educate, train, and value expertise (curricula and competence); and the interrogation of how we extract knowledge from the dead (collections). Given the academic and practical value of forensic anthropology, especially vis-à-vis its consequences for colonized peoples, these discourses become imperative for the field's continued maturation.

2 Rethinking Categories

Classification by categorization has figured prominently in anthropology since its inception as race science and continues as a point of critique today (Pels 2022). In forensic anthropology, categorization appears most prominently when sex and race/ancestry are estimated from a set of unidentified remains. These parameters, especially the latter, are also arguably the most contentious components of the biological profile because they map most imperfectly over the spectrum of identity.

Colonization made possible the inspiration for categorizing the world into racial typologies, which itself laid the foundation for ancestry estimation. Racial categories have changed over time, most notably from the -oids in race determination to continental groupings in ancestry estimation, although this change merely represents a linguistic shift to distance anthropologists from a thoroughly discredited view of human variation. On the surface, terminological changes claim to correlate more strongly with human population history and geography, but on a deeper level merely operate as a euphemism for race (Pilloud et al. 2021; Tallman et al. 2021). Ancestry as a term finds itself again reincarnating as population affinity estimation. Proponents for the latter claim that what forensic anthropologists are actually attempting to estimate is similarity at the level of contextualized local rather than generalized global variation, which better reflects genetic population structure due to geography, isolation by distance, assortative mating practices, and other factors at the intersections between microevolutionary forces and culture and history (Ross and Pilloud 2021; Spradley and Jantz 2022). What seems consistent, however, is that “the ways in which individuals are grouped together determine the genetic [or physical trait] frequencies that are attributed to such populations, not that genetic [or physical trait] frequencies determine how to group individuals into populations” (Foster and Sharp 2004, 792). In all such proposed taxonomies, colonizers make the labels by which groups are called, the truncations by which groups are divided, and the rules by which groups can interact. These are paramount considerations when calls for the adoption of population affinity necessitate the contextualization of local population history.

While much work has been done to dispel a biological basis for racial categories, forensic anthropologists—particularly in racially diverse, settler colonial contexts such as the United States, South Africa, Brazil, and Australia, among others—continue to rely on ancestry estimation as core practice. The crucial justification for the continued use of ancestry estimates is that it relies on a probabilistic translation of “biological traits to a culturally constructed labelling system” (Sauer 1992, 109) and that it is this labelling system that is supposedly useful in missing persons investigations. To this latter supposition, it is still unknown how helpful or crucial knowing the ancestry of a person actually is in identifying someone, even if anthropologists are highly accurate in estimating it (see Parsons 2021). Furthermore, race is constructed differently under different contexts, and thus has highly varied utility, if any at all (see Cabana and Di Fabio Rocca 2025).

On the other end of this debate are calls for the abandonment of ancestry estimation altogether, what Bethard and DiGangi (2020) term a “lost cause”. In their letter to the forensic anthropology community, they call for a moratorium on ancestry estimation and for scrutiny of its actual contributions to the identification process. They raise the possibility that racial bias on the part of the investigator towards non-European descended decedents (determined via ancestry estimation) will disincentivize thorough identification efforts. Stull et al. (2021) rebut that the high accuracy of ancestry estimates in identified cases, the strong concordance between genomic and self-reported ancestry, the utility of ancestry estimates in repatriating Native American remains, and the record of forensic anthropologists advocating for more method representation of underrepresented groups warrant its continued use. Moreover, there is no evidence to suggest that the ancestry estimates provided by forensic anthropologists to law enforcement predispose these agencies to prioritize certain cases over others along racial lines (Hughes et al. 2023; Yim and Passalacqua 2023). However, there is ample evidence of racial bias in policing writ large (DiGangi and Bethard 2021). To further counter these points, DiGangi and Bethard (2021) employ critical race theory to demonstrate the often-invisible nature of systemic racism, such that the continued use of ancestry categories makes forensic anthropologists unintentionally complicit in white supremacy and reifies to stakeholders that race is biological.

Intertwined with racial categories, Western colonialism used the ideology of a strong sex binary as a ranking measure of racial advancement wherein white Europeans, by virtue of possessing, in their own estimation, the highest degree of sexual and gender difference, were at the pinnacle of evolution (Markowitz 2001). An interrogation of the sex binary does not deny the existence of a highly consistent and dimorphic human sex system based on characteristics of genetics, gonads, and genitalia—referred to as 3G-sex—but argues that “using 3G-sex as a model to understand sex differences in other domains … leads to the erroneous assumption that sex differences in these other domains are also highly dimorphic and highly consistent” (Joel 2012, 27). Even within this system's characteristics, as with hormones, cells, brain function, metabolism, secondary sex characteristics, body fat, body size, psychology, and social norms, among other vectors of anatomy, physiology, behavior, and culture, traits are demonstrably spectral and multivariate (Ainsworth 2015; Fausto-Sterling 1993, 2000; Fuentes 2023; Moore 1968).

In the domain of forensic anthropology, skeletal size and shape differences are used for the identification of an unknown individual's assigned sex at birth, presuming that they were only afforded two options in life. Work that challenges this binary, whether in terms of terminology (Flaherty, Johnson, et al. 2023; Stewart and Delgado 2023), methodology (Flaherty, Byrnes, et al. 2023; Schall et al. 2020), or theory (Adams et al. 2023; Haug 2022; Tallman, Kincer, and Plemons 2022), and especially towards the identification of intersex, transgender, and gender diverse persons, can be seen as decolonial in that colonization forced upon the colonized this binary ideal (O'Sullivan 2021).

As an extension of centering racial and gendered inequalities, forensic anthropologists are increasingly interested in studying how structural violence is embodied in the skeleton. Several researchers, for instance, have used skeletal indicators of stress to assist with “categorizing” cases along the US–Mexico border between undocumented border crossers and American citizens (Beatrice and Soler 2016; Beatrice et al. 2021; Birkby et al. 2008; Weisensee and Spradley 2018), relying on the fact that colonialism has restricted ready access to healthcare, nutrition, and security for many who live south of the United States. As the effects of colonialism are far-reaching and not simply palpable across national borders, diagnosing poverty from the skeleton has also been attempted within communities in the United States (Moore and Kim 2022). Running parallel to the identification utility of the biological profile, terms such as the structural vulnerability profile (Winburn, Wolf, et al. 2022), cultural profile (Birkby et al. 2008), or biocultural profile (Beatrice and Soler 2016) have been proposed. Reineke et al. (2023) take issue with the implications of a “profile”, cautioning against letting estimations of inequality descend towards a categorical approach to human variation that could stigmatize and further marginalize forensic cases—a sentiment shared by Gruenthal-Rankin et al. (2023), who question how such a profile may be (ab)used beyond the case report that contains it.

3 Rethinking Casework

Casework in forensic anthropology is conventionally portrayed as solitary, with the lone anthropologist acting as a disinterested expert witness to the individual skeleton before them. This disinterestedness is often seen as a crucial component of the scientific endeavor, stemming from the positivist view that objectivity is the only way to explain observable phenomena (Schnegg 2015, see “Rethinking Curricula” below). Superficially, claims to pure objectivity or neutrality insulate the forensic anthropologist from accusations of bias and emotion that could discredit their findings, especially during cross-examination in criminal court proceedings (Marten et al. 2023). More deeply, however, objectivity and positivism were welcomed embrocations for the horrors of colonialism when they mobilized the scientific method to subjugate and inferiorize the colonized (see Cohn 1996; Richards 1993). In that sense, maintaining a position of objectivity is a form of colonial privilege in that colonialism ensured forensic practitioners identifying as Black, Indigenous, Hispanic, Asian, and persons of color must forever struggle with decoupling their lived experiences from the unjust systems put in place by colonialism, if even at all possible (Winburn and Clemmons 2021). This is in step with Du Bois's (1903) double consciousness, which obliges the racialized to simultaneously perceive themselves as within and outside of the coterie. For the colonized, objectivity is a lofty ideal that comes most easily to white scientists because they themselves designed the escape hatches within the oppressive systems all scientists are expected to ignore in the name of objectivity. In response, the plausibility for activists–scientists has been defended despite clamors that these two roles represent a conflict of interest in the forensic sciences (Adams et al. 2022, 2024; McCrane et al. 2022).

In contrast to the individualist model of the disinterested scientist working in isolation from external pressures, the deployment of forensic anthropology in resolving missing persons from Argentina's dirty war during the 1980s provides a more community-centered paradigm. Initial investigations by the nascent Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (EAAF) involved the active participation of family members of the missing, particularly women relatives, from its very first exhumations (Fondebrider 2016). In fact, EAAF's insistence to incorporate family perspectives, even when oppositional or divided, became “their most recognizable signature” (Rosenblatt 2015, 90). Members of EAAF were Argentinian themselves, grew up in the shadow of the war, worked in concert with grieving relatives, and were emotionally invested in telling the stories of the people they were unearthing. Could their work in this case proceed objectively, does a perceived lack of objectivity detract from the legitimacy of their findings, or is objectivity a social construct of Western forensic science? A rarity in Global North casework, it is now commonplace for community stakeholders intimately victimized by the very atrocities being investigated to be present at exhumations, contribute to examinations, and lead the charge to investigate (e.g., Klonowski 2007; Mazzucelli and Heyden 2015; Reineke 2022; Zarrugh 2022).

Over the past 40 years, what started with EAAF's groundbreaking work in Argentina has burgeoned into a global phenomenon of deploying forensic science in the aftermath of large-scale human suffering—an emerging field into its own coined humanitarian forensic action by the International Committee of the Red Cross (Tidball-Binz and Cordner 2022). In many cases, these deployments seek to reconcile atrocities directly produced by colonialism, such as the genocide of Indigenous Americans and Canadians through residential schools (Kim and Moore 2022; Montgomery and Supernant 2022; Nichols 2021) or African enslavement and apartheid (Cardoso et al. 2019; Ellsworth 2021; Hartemann 2021; Mack and Blakey 2004; Rousseau 2015). In other cases, the dénouement of colonialism and imperialism facilitated the ideal conditions for widespread deaths from mass migration, political instability, environmental degradation, and ethnic tensions, compelling forensic science to intervene (Cattaneo et al. 2015; Fleischman 2016; Koff 2004; Latham and O'Daniel 2018; Noel Jr. and Torres-Ruiz 2021).

Despite the positive image of humanitarian forensic action as a moral and public good, its implementation is nevertheless susceptible to neocolonial practices. Take, for instance, the forensic investigations conducted under the auspices of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which were seen by many as furthering the trauma experienced by local communities because outside experts failed to consider culturally appropriate ways of acting (Jesse 2012; see Uwizeye and Rutherford 2023, for the case of intergenerational harms). International investigations in the Balkans focused on collecting legal evidence to establish the actus reus of the crimes committed in lieu of meeting the humanitarian needs of victims' families to identify their loved ones, creating tensions (Crossland 2013; Stover and Shigekane 2002; see Van Baarle 2019 for the Rwandan case). In Canada where a known Indigenous burial ground was unearthed to make way for a parking garage, the state's vision of transitional justice directly clashed with victims' perceptions of reconciliation, reifying what Indigenous community members saw as the continuation of colonial violence (Kim 2018b). As these examples demonstrate, external actors run the risk of a parachute humanitarianism reminiscent of colonial powers that arrive with chauvinistic intentions and leave a place and peoples worse off. Furthermore, the finality that forensic humanitarian actors sometimes promise in “settling” past atrocities—with dicta like bones never lie or bones bear witness—perpetuates the wider myth that forensic anthropologists provide closure through their casework (Cirilo 2022; Moon 2013). Closure as a commodity and service is redolent of colonial bureaucrats drawing borders, closing shop, and washing their hands of accountability once their colonial projects ended in revolution. Instead, success has been found in community-grounded approaches that consider positionality, allow multiplicity in methods, and center trauma-informed relationship-building and emic prerogatives (Elgerud and Kim 2021; Kim 2018a; Kim and Rosenblatt 2023; Kim et al. 2022; Redeker and Steadman 2023; Rosenblatt 2019).

4 Rethinking Curricula

The coloniality of knowledge, whether historic or contemporary, is one in which the Other is of irrational mind and thus whose philosophy is illegitimate (Bhambra and Holmwood 2021; Maldonado-Torres 2007; Mungwini 2017; Quijano 2000). Taken a step further, Western reason, because it is “objective,” “neutral,” and “apolitical,” is superior and thus can be deployed anywhere and imposed everywhere (Adams 2021), including higher education pedagogy. Wider calls in higher education to decolonize the curriculum shift the mindset of what constitutes a curriculum from “what is taught” to “what gets taught”, bringing to the fore the power of the privileged to maintain a status quo—namely, a male, white, and Western epistemology (Lindsay 2020). Thus, to decolonize means not only to include teaching materials from more diverse perspectives, but also to completely rethink what knowledge is, how it can be formed, and how it can be taught (Lindsay 2020). Different axes of justice figure prominently in these discourses as a means to rebalance the academic record away from one that is unjustly favored, including cognitive or epistemic justice (the right of different knowledge systems to co-exist; Fricker 2007; Visvanathan 1997), research justice (the legitimization of community members as partners and leaders in the research process; Assil et al. 2015), and citational justice (the simultaneous intentionality of citing authors from marginalized voices and the rejection of citation metrics as adequate measures of impact and excellence; Mott and Cockayne 2017). Despite these efforts and because of their rising popularity, Moosavi (2020) warns of the pitfalls of riding the “decolonial bandwagon” that can ironically move decolonization work in the Global North towards neocolonialism through reductivism, appropriation, essentialism, nativism, and tokenism.

Forensic anthropology straddles anthropology and forensic science, benefiting from being in dialogue with multiple discipline-specific movements to decolonize curricula. Mogstad and Tse (2018) outline the common sentiments of colonized scholars pursuing anthropology education in the Global North. Namely, that syllabi are organized around Western canon, philosophy, and hierarchy; that the romanticization of fieldwork conveys an entitlement to treat the world as an open laboratory with materials for the taking; that the teleological emphasis is disciplinary advancement over interdisciplinarity or extra-academic conversation; and that discomfort with decolonization is uncritically relegated as identity politics or cultural essentialism. From the forensic science silo, decolonization has been dismissed by some as incompatible or unapplicable to analytical sciences and counterproductive to quality assurance as it allegedly dilutes curricula with “lower quality” references and contradicts the scientific falsification principle; however, what decolonizing curricula hopes to achieve is greater transparency in how discoveries and methodologies are generated and validated, thus increasing quality (Chaussée et al. 2022). Recent pushes to diversify forensic anthropological curricula include incorporating structural vulnerability frameworks into pedagogy (Litavec and Basom 2023; see “Rethinking Categories” above), identifying barriers to entering and succeeding in the profession (Goliath et al. 2023; Spiros et al. 2022; Tallman and Bird 2022; Tallman, George, et al. 2022; Tegtmeyer Hawke and Hulse 2023), widening the historical narratives taught to include people of color (Go et al. 2023), calling out citational practices (Go et al. 2021), and clarifying mentorship paradigms (Winburn et al. 2021).

5 Rethinking Competence

Measures of competence in forensic anthropology are unique among the specialties of biological anthropology because of professional certification and increased standardization and regulatory oversight across the forensic sciences (Langley and Tersigni-Tarrant 2020; Passalacqua and Pilloud 2020, 2021). While board certification is not a legal prerequisite for practice, it is regarded by some as the highest credential in the field. Currently, there are four regional bodies that certify expertise: the American Board of Forensic Anthropology, the Asociación Latinoamericana de Antropología Forense, the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Forensic Anthropology Society of Europe, each with varying minimum requirements in education, training, and experience for eligibility. However, there is some degree of consensus on the necessary training and experience needed to be a good forensic anthropologist (Marten et al. 2023).

Through education the American colonial state bred a new elite of Filipinos trained in a new, more ‘modern,’ American system. People with advanced degrees like law or engineering were at the apex of this system. Their prestige, as such, not only rested on their purported intelligence, but also their mastery of the colonizer's way of life. (Claudio 2010)

For Frantz Fanon (1952), the colonized seek excellence in the skills valued by the colonizer so as to be recognized as equals, yet this in actuality further subordinates them to their masters.

Credentialing can reinforce the notion that there is only one recognized path to becoming a forensic anthropologist, which excludes those without sufficient resources or from nontraditional backgrounds—often as a result of being colonized—and deflates the experience of those in contexts without specialized programs or certifying bodies. Indeed, anthropologists from the Global South, Africa and Asia in particular, have little means to “prove” their worth according to the Western gaze, despite these areas having the highest and most challenging caseloads from armed conflict and disaster-related incidents (Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft 2023; The International Institute for Strategic Studies 2023). Certification is not unwelcome in itself, but care should be taken in disallowing the status it confers to lend credence to the myth of a meritocracy. It is well established that unequal access to opportunities (e.g., disapproval of foreign degrees, visa requirements, English proficiency exams) and unequal recognition (e.g., racist citation practices, socially determined funding success, friendship-based academic communities) are strongly driven by colonial legacy.

6 Rethinking Collections

The evolution of professional ethics in forensic anthropology has centered around developing principles of nonmalfeasance, respect for persons, and stewardship, among others (Passalacqua and Pilloud 2018). Part of these ethical considerations critically considers how we extract knowledge from the dead, both in research and casework. As custodians of human remains, whether at educational or medicolegal institutions, forensic anthropologists have ethical obligations of care for the deceased with due consideration for the wishes of descendant communities. This is especially salient when interacting with Indigenous and enslaved remains, so as not to perpetuate historical harms, and with modern cases, where families are already in vulnerable states of grieving. Recent and recurring scandals in both these spheres of practice consistently reignite debates on the responsibilities anthropologists take on as stewards: Elizabeth Weiss and her views on repatriation (Flaherty 2022); Harvard's possession of thousands of Native American and enslaved African remains (Chang 2022) and the illegal sale of body parts from its medical school's Anatomical Gift Program (Levenson 2023); the online display and use in teaching of the remains of a Black child murdered by police in the 1985 MOVE bombing (Monteiro 2023), and the retention of homicide victims in Florida against the wishes of family members (Dobkin 2023; Payne 2015), to name a few. While these stories are sensational, those familiar with the history of colonialism and the mentality that justified its existence know they are not new or isolated.

Many of the collections on which knowledge is built have been amassed under ethically dubious or outright racist histories of violent colonial extraction that targeted the disenfranchised (e.g., Agarwal 2024; de la Cova 2020; Hildebrandt 2021; Morris 1987). Indeed, many museums in the present day represent crime scenes of the colonial past (Kasibe and Maxwele 2023). Despite this, some anthropologists claim they have the right to study the dead because they have the right to scientific inquiry under the general provision on freedom of expression; because the interests of the living outweigh those of the dead; and, perhaps most frequently espoused, because scientific discoveries benefit the common good of humankind (Hibbert 1999; Walker 2000; Walsh-Haney and Lieberman 2005). However, such views are inherently unanthropological as they afford little value to diverse cultural perspectives on the rights, personhood, and psychic power of the dead, as many Indigenous traditions hold (Klesert and Powell 1993; Metzger 2025). Instead, these claims actually disguise Western values of individualism (rights of the scientist over the rights of others), capitalism (maximized gains, minimized costs), and ownership (humans possessing humans). A decolonial lens casts light on these arguments by interrogating which group in power penned these rights and whose “common good” is really benefiting. Even so, the contemporary restitution of remains from these collections or the ethical framing of modern-day best practices can just as easily fall into neocolonial traps because Western values continue to spearhead these operations (Kurzwelly and Wilckens 2023; Tsosie et al. 2023).

More recent collection efforts have attempted to address these ethical issues by focusing on willed donations or medical imaging data with informed consent, though these have their own challenges with regards to ethnic and socioeconomic diversity (Campanacho et al. 2021). The overrepresentation of European-descended individuals not only in collection compositions, but also in research methodology reinforces an already strong “historic tendency to measure all human variation against one particular norm” (Go et al. 2021, 154). Winburn, Jennings, et al. (2022) recognize the reticence of minorities, specifically African Americans, to donate their bodies to science because of past and continuing abuses that exploit minoritized bodies. Instead, they argue for centering Black perspectives and community outreach as ways to ameliorate this gap (Winburn, Jennings, et al. 2022). Lans (2021), for instance, uses perspectives from Black feminist theorists and artists to decolonize the anonymity and anatomization of Black women accessioned into the Huntington skeletal collection. Dunnavant et al. (2021) further lobby for legislation to protect African American remains in universities, museums, and unmarked graves, modeled after the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Such collaborative and interdisciplinary paradigms are not simply wishful imaginations, as several case studies such as the New York African Burial Ground Project (Blakey 2008), the Cobb Skeletal Collection (Watkins 2020), and human rights work (see “Rethinking Casework” above) prove scientists and communities can achieve success when they work in concert.

7 Conclusions

Just as reverberations of colonialism are at work today, often in insidious ways, so too are efforts in forensic anthropology to dismantle these systems that are not always readily appreciable as decolonial. The composition of collections, the history of the field, the embodiment of structural vulnerability, or the estimation of ancestry are obvious arenas with easily dissectible colonial ties, but so too are the nature of casework, the certification of expertise, and the objectivity of science if we look critically enough. Because research and practice in forensic anthropology run so proximally to colonized bodies at their most vulnerable—in death—the onus to decolonize becomes even more urgent. To find colonial threads to unravel, look for signs of individualism, capitalism, extraction, positivism, universalism, essentialism, fundamentalism, and power relations and inject alternative imaginings of pluralism, interpretivism, inclusivity, holism, and of course, cultural relativity. Notwithstanding efforts to decolonize, colonialism is sticky and decolonial practices are not immune to neocolonial resurrections.

It is not by coincidence that a large portion of the works cited herein are from 2020 onwards, a time when COVID-19 restrictions were at their peak and the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police ignited protests against racial inequality and police brutality across the United States and the world. In this regard, forensic anthropology is relatively late in its response to what are now decades-old calls to decolonize, perhaps in part due to its alignment with law enforcement, government, and the criminal justice system. While I phrase this uptick in discourse as a “turn” in forensic anthropology, the decolonization movement in general is not one that can be attributed to a particular historical moment or field. Rather, its very nature is conglomerative of the many generations of academics, political activists, and revolutionaries working under different conditions, positionalities, and motivations. Consequently, there are many avenues through which to decolonize, here through the five “C's” but always with the potential for more. Rethinking categories requires reconsidering identity itself, whether it be an identity imposed by the state, an identity expressed by the decedent, or the conditions that (dis)regulated that imposition and expression. Rethinking casework expands how, when, where, and with whom forensics is deployed and for what purpose. Rethinking curricula and competence criticizes how one gets to become a forensic anthropologist, under whose rules, both formal and unspoken, and in whose image. Lastly, rethinking collections recasts remains themselves from inert objects of ownership to active participants in community with the living.

From the undercurrents of these five “C's”, a sixth C common among them rises to the surface: care (G. Cabana and S. Athreya, personal communication, October 11, 2023). Care can act as an ethical north star that resettles practitioner, stakeholder, and beneficiary as collaborators instead of as chains in an assembly line. With care at the forefront, greater sensitivity is afforded to how forensic anthropology is practiced, taught, and researched relative to its repercussions not only for the dead, but also for the living, and especially for the colonized. However, care can also be commodified when treated as a good to be delivered instead of as a process to be incorporated (G. Uwizeye and J. Rutherford, personal communication, October 11, 2023), thereby producing a myth of care and reproducing a concept of care that itself needs to be decolonized (G. Cabana, personal communication, October 11, 2023).

One of the principal critiques of forensic anthropology is that it is merely a toolkit or trade, not a scholarship, because it lacks a theoretical basis (Adovasio 2012). This is, of course, untrue but excusable given the tendency for publications to have an obvious focus on method and only an implicit allusion to theory; forensics, by definition, is decidedly applied. Winburn, Yim, et al. (2022) take aim at this critique by making explicit how evolutionary theory underpins method generation and interpretation. As this paper shows, decolonial theory also provides a rich and apposite wellspring from which to draw upon and should likewise be made explicit. When accepting colonialism as the sine qua non of modern inequality, as decolonial theory posits, previously unlit paths reveal themselves. Like with evolutionary theory, decolonial theory can generate new methods and problematize old ones. It builds a critical consciousness that can test assumptions, uncover biases, and deconstruct dominant narratives. It can motivate the field to expand in its scope, ethics, membership, and clientage. It encourages interdisciplinarity and builds solidarity across diverse struggles for justice. As a matter of survival, decolonization vindicates the continued relevance of a colonialist field in an ostensibly postcolonial world.

Author Contributions

Matthew C. Go: conceptualization (lead), data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), investigation (lead), methodology (lead), project administration (lead), resources (lead), visualization (lead), writing – original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (lead).

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the generosity of Dr. Sheela Athreya and Dr. Rachel Watkins for not only conceiving this special issue and organizing its accompanying writing workshop, but also for believing in my added value to this cadre of luminaries through their invitation. This work benefited immensely from the aforementioned workshop, with intellectual contributions from Graciela Cabana, Andreana Cunningham, Francisco Di Fabio Rocca, Michelle Glantz, Wandile Kasibe, Inza Koné, Aja Lans, Chumani Maxwele, Jamie Metzger, Betsy Nelson, Robin Nelson, Julienne Rutherford, Rick Smith, Krystal Tsosie, and Glorieuse Uwizeye. Dr. Anna Agbe-Davies as principal discussant, along with Dr. Madhusudan Katti and Dr. Jonathan Marks, provided great direction and valuable insight for the piece, as well as set a felicitous tone for the issue. Two anonymous reviewers provided constructive feedback that benefited the initial draft of this manuscript. Many thanks also to Missy Gandarilla for her administrative support and comradeship. Funding for the workshop was awarded to Dr. Athreya through Texas A&M University's Chancellor's Edges Fellowship and President's Impact Fellowship, and additionally to Drs. Athreya and Watkins through a grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.