Where and How: Stone Tool Sites of the Endangered Sapajus flavius in a Caatinga Environment in Northeastern Brazil

ABSTRACT

The blonde capuchin monkey (Sapajus flavius) was, until a few years ago, an endemic primate of the Atlantic Forest. Today, populations inhabit the Caatinga dry forest and these have been documented using stone tools to access encased foods. It is important to know the distribution of these sites and the characteristics of the stone tools to inform conservation actions for this primate in the Caatinga. To this end, we identified and characterized stone tool sites used by a group of blonde capuchin monkeys in the Caatinga dry forest of northeastern Brazil. For 8 months, we walked two pre-existing trails to georeference the stone tool use sites, to measure the dimensions and weight of the anvils and hammerstones, and to identify the food items processed at the sites. A total of 215 anvils and 247 hammerstones were mapped. The anvils were significantly longer than the hammerstones, while there was no difference in width. Most food remains found on the anvils were old (n = 101; 91%). Cnidoscolus quercifolius (n = 85; 77.3%) and Prunus dulcis (n = 25; 22.7%) were most common among the plant species found on the anvils. The width, thickness, and weight of hammerstones used to crack fruits of P. dulcis were significantly greater than those used to crack C. quercifolius. These results should be used as a baseline for the development of conservation actions for the species and habitat.

Summary

-

Our study mapped blond capuchin stone tool use sites in the Caatinga, revealing a novel database for this endangered species with most sites featuring only one hammerstone

-

Blond capuchins used significantly larger hammerstones for cracking P. dulcis compared to C. quercifolius, showcasing how tool dimensions correlate with food hardness

1 Introduction

Some animals use tools to search for and access food (Emery and Clayton 2009; Mann & Patterson 2013; Seed and Byrne 2010). Nonhuman primates stand out as using a wide variety of tools across a variety of environments (Souto et al. 2011; Malaivijitnond et al. 2007; Sanz and Morgan 2007). Stones or branches are mainly used to crack encased foods and plant probes are used to access invertebrate nests (Gumert, Kluck, and Malaivijitnond 2009; Mannu and Ottoni 2009; Mendes et al. 2015; Fragaszy et al. 2004; Sanz, Morgan, and Gulick 2004; Ohashi 2015). Although not exhibited by the majority of species, diverse species of primates use stone tools to access resources, from arid to coastal environments (Malaivijitnond et al. 2007; Barrett et al. 2018; Falótico et al. 2017; Spagnoletti et al. 2011; Valença, Oliveira Affonço, and Falótico 2024; Luncz et al. 2020).

The sites where percussive stone tool use occurs, known as “tool use sites” or “processing sites,” are identified by the presence of larger stones or logs (anvils) on the ground and smaller stones (hammers) (Visalberghi et al. 2007). Anvils can be identified by the presence of stones potentially used as hammers and food items processed on or near them, and sometimes by use wear such as pitting, from the cracking process with stones (Visalberghi et al. 2007; Ferreira, Emidio, and Jerusalinsky 2010). Tool use is habitual in some populations of bearded capuchin monkeys (Sapajus libidinosus) and individual blonde capuchin monkeys (Sapajus flavius) (Ottoni and Izar 2008; de A. Moura and Lee 2004; Mannu and Ottoni 2009; Souto et al. 2011; Lima et al. 2024). Within these species, the use of stones and probes has been documented for cracking encased food, digging tubers, flushing prey, and collecting termites (Ottoni and Izar 2008; de A. Moura and Lee 2004; Mannu and Ottoni 2009; Santos 2010; Souto et al. 2011). The use of stones was documented mostly widely among bearded capuchin monkeys in the arid and semi-arid Caatinga and Cerrado-Caatinga ecotone (de A. Moura and Lee 2004; Mendes et al. 2015). While bearded capuchins are widely known for using stone as a tool to access encased food (Fragaszy et al. 2004; Ottoni and Izar 2008; Falótico et al. 2024; Valença, Oliveira Affonço, and Falótico 2024); blonde capuchin monkeys have been reported to do so in fewer published studies to date (Ferreira, Emidio, and Jerusalinsky 2010; Garcia et al. 2020; Lima et al. 2024).

The blonde capuchin monkey was rediscovered 18 years ago and was quickly included among the 25 most endangered primates of the world (Oliveira and Langguth 2006; Mittermeier et al. 2012). Today, this primate is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List, mainly due to the reduction of forest cover (Valença-Montenegro et al. 2021). The distribution range of blonde capuchin monkeys was thought to be limited to the Atlantic Forest fragment located in the Pernambuco Endemism Center (Fialho et al. 2014). In this region, ecological and behavioral aspects of the species (Bezerra et al. 2014; Bastos et al. 2018; Lins and Ferreira 2019; Medeiros et al. 2019; Andrade, Freire-Filho, and Bezerra 2020) as well as its habitat (Guedes et al. 2023) are known. However, recent studies have documented the presence of blond capuchin monkeys in the Caatinga environment (Ferreira, Emidio, and Jerusalinsky 2010; Garcia et al. 2020; Martins et al. 2023). To date, data related to the population of blonde capuchin monkeys inhabiting the Caatinga are linked to the potential and use of stone tools (see Ferreira, Emidio, and Jerusalinsky 2010; Garcia et al. 2020; Lima et al. 2024), distribution range (Ferreira, Emidio, and Jerusalinsky 2010), and influence of size and protection of native forest on the local occupancy (Lins et al. 2022). Mapping and characterizing the stone tools and processing sites used by blonde capuchin monkeys are the first steps to know the pattern of this behavior for the species.

This study identified and surveyed the stone tool sites used by blond capuchin monkeys, S. flavius, in a Caatinga environment in northeastern Brazil. Specifically, we (1) described the dimensions of hammers and anvils used by blonde capuchin monkeys, and (2) compared the weight, thickness, length, and width of hammerstones used by blonde capuchin monkeys to crack, the two most commonly exploited foods found on the anvils. Finally, we compiled an initial list of plant species exploited by blonde capuchin monkeys with and without percussive tools. This study provides the first baseline for systematic behavioral studies of the species in the Caatinga environment, thus contributing to the goals of the National Action Plan for the Conservation of Northeastern Brazil.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Area

This study was conducted in an environment of Caatinga contained within of the Monumento Natural do Rio São Francisco - MNRF. This protected area is located in five municipalities - Piranhas, Olho D'água do Casado, Delmiro Gouveia, Paulo Afonso, Canindé de São Francisco - in the northeast of Brazil. The MNRF was created in July 2019 to conserve natural ecosystems of great ecological importance and scenic beauty, allowing scientific research and the development of environmental education activities, recreation in contact with nature and ecological tourism. This protected area includes approximately 27,000 hectares of Caatinga terrain along the São Francisco River. Within this protected area, pasture occupies 39.3% (equivalent to 320 km2) due to the expansion of cattle ranching activities, while Caatinga terrain occupies 27.2% (approximately 221 km2) (Lima et al. 2019). The region experiences a rainy season from May to June, with precipitation occurring primarily in May. Annual rainfall ranges between 500 and 700 mm (Radambrasil 1983). Local temperatures show minimal variations, with an annual average of 25°C, rising to over 27°C during the hottest months and falling to 20°C during the coldest months (INPE 2001).

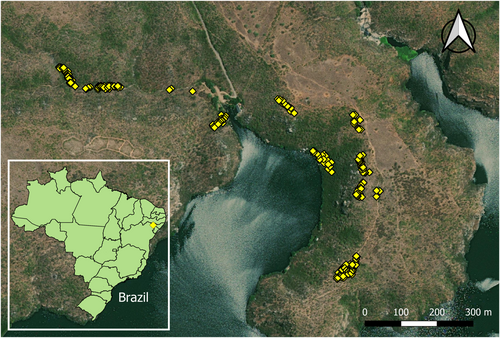

2.2 Data Collection

The data were collected in an area located in the municipality of Delmiro Gouveia (9° 27’ 35” S, 38° 01’ 48” W). To map the stone tool use sites used by blond capuchin monkeys, we walked two pre-existing trails in the study area from November 2023 to May 2024. We spent 6 days each month on the ground examining lithic processing sites (see Falótico et al. 2024). These processing sites are identified by the presence of a flat surface used as a substrate for the processed encased food, referred to as “anvils,” a stone with traces of use - such as marks or food remains attached - on the anvil, referred to as “hammers,” and remains of the processed encased food on or near the anvil (Falótico et al. 2018). In this study, we only considered the food resources found on the anvils.

When a processing site was identified, we collected the geographic location using a handheld GPS (GPS Garmin Etrex), anvil size (length and width), hammer size (maximum length, width, and thickness), and weight (see Falótico and Ottoni 2016), processed encased food, and its approximate age (fresh or old, based on color and integrity). We used two scales (model Pesola 1000 g and 5000 g) to measure weight, calipers (to the nearest 0.1 mm) to measure length, and measuring tapes to measure length and distance greater than 15 cm.

We compiled a list of plant species used by blond capuchin monkeys with and without stone tools during the study period. To do this, we used the three sampling protocols. In the first protocol, we identified the food remains found at the processing sites. In the second, we used passive monitoring through camera traps. Thus, we randomly installed 16 camera traps (model Suntek HC-801A) to obtain behavioral, ecological, and ancillary data related to stone tool use by blonde capuchin monkeys. We installed the camera traps on the trunks of the trees, 30–40 cm above the forest floor. We programmed the traps to take photos (one photo) and videos (60 s) at 30-second intervals. The photos were taken at a resolution of 24MP, while the videos had a resolution of 1080 pixels. The sampling effort comprised a total of 3360 camera trap days where each day corresponded to 24 h. Finally, in the third protocol, we used the ad libitum procedure (Altmann 1974) in the presence of the blonde capuchin monkeys. We totalized 210 h of fieldwork activities (walking on the trails and monitoring the anvil sites). In the final, we obtained ad libitum samples during 170 min of direct observation (7.41% of total time). We tried to identify food items that we saw monkeys eating. The processed and exploited foods were collected and identified by a local field assistant. When possible, fertile branches were collected for identification and deposited in the Geraldo Mariz Herbarium of the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco.

2.3 Data Analysis

We considered each processing site as a sampling unit in our analysis. For the list of plant species exploited by blonde capuchin monkeys in the study area, we identified the food item exploited. We calculated descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of anvil size (length and width), hammerstone size (length, width, and thickness), and weight for all anvils and hammerstones, and separately for those with remains of the two most commonly processed foods. To test the variation in the size of anvils and hammerstones, we used a generalized linear model (GLM) with the independent variables being tool type (anvil or hammer) and the dependent variables being stone length and width. To test whether the characteristics of hammers and anvils differed according to the two most commonly processed foods, we used GLMs to test the effect of the independent variables (encased-food type) on the dependent variables (hammer-stone tool dimensions). A gamma distribution for the dependent variable with a log link function was used for all of the above GLM tests. The assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance of the model residuals were verified using the DHARMa package (Hartig 2022). Moreover, the coefficient of determination (McFadden's R-squared) was calculated for each model using the ISLR package (James et al. 2022).

3 Ethical Notes

All procedures were performed in accordance with Brazilian law, under the approval of the environmental authorities IBAMA/ICMBio (approval #25727), and in compliance with the American Society of Primatologists Principles for the Ethical Treatment of nonhuman Primates.

4 Results

During 42 days of fieldwork (November 2023–May 2024), we walked 1.514 km along two pre-existing trails at MNRF (Figure 1). We identified 215 processing sites and 247 hammers (Figures 1 and 2, and Table 1). In overall terms of hammerstone dimensions, the mean values found were: width - 66 mm (± SD 36), length - 91 mm (± SD 36), thickness – 41 mm (± SD 52), and weight 337 g (± SD 483) (Table 1). Regarding the number of hammers found on the anvils, most of the processing sites presented only one hammer (n = 185; 86%), followed by two hammers (n = 24; 11.2%) and three hammers (n = 6; 2.8%). Generally, the anvils presented a mean length of 470 cm (± SD 57) and a mean width of 600 cm (± SD 500) (Table 1). When compared the dimensions between hammers and anvils using the GLM, we found variation in length (GLM: Chi-square = 47.0, df = 455, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.18); however, we found no difference in width (GLM: Chi-square = 0.46, df = 455, p = 0.443, R2 = 0.002).

| Weight (g) | Length | Width | Thickness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anvil (N = 215) | — | 470 cm ± SD 570 (2.07–483) | 600 cm ± SD 500 (6–64) | — |

| Hammer (N = 247) | 337 ± SD 483 (20 - 4.300) | 91 mm ± SD 36 (101–190) | 66 mm ± SD 63 (21.3–130) | 41 mm ± SD 52 (11–90) |

To date, we have identified nine plant species utilized by blond capuchin monkeys (Table 2) using three sampling protocols. Four plants were exclusively recorded using camera traps, one exclusively for the ad libitum protocol, and one exclusively for food remains. Three plant species were recorded using at least two protocols (Table 2).

| Family | Species | Native/exotic | Part of fruit exploited | Exploited with stone tool | Type of observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euphorbiaceae | Cnidoscolus quercifolius Pohl | Native | Seed | Yes | Food remains and camera trap |

| Rosaceae | Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb | Exotic | Seed | Yes | Food remains and camera trap |

| Malpighiaceae | Malpighia emarginata DC. | Exotic | Pulp | No | Ad libitum |

| Bromeliaceae | Bromelia laciniosa Mart. ex Schult. & Schult.f. | Native | Leaf | No | Camera trap |

| Neoglaziovia variegata (Arruda) Mez | Native | Leaf | No | Camera trap | |

| Fabaceae | Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC. | Exotic | Pulp | No | Ad libitum and camera trap |

| Cenostigma pyramidale (Tul.) Gagnon & G.P. Lewis | Native | Seed | Yes | Food remains | |

| Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | Exotic | Pulp | Yes | Camera trap |

| Cactaceae | Tacinga inamoena (K. Schum.) N.P. Taylor & Stuppy | Native | Pulp | Yes | Camera trap |

Five plant species were used exclusively with stone tools (Table 2). A total of 137 processing sites with the presence of food remains were recorded. Of these, 118 food remains (86.1%) were identified. Processing sites with only one type of food remains represented 90.5% (n = 124), while those with two or more types of food remains represented 9.5% (n = 13). We recorded 111 processing sites with the presence of only one type of food remains identified. Of these, 6.3% (n = 7) had only fresh food remains, 91% (n = 101) had only old food remains, and 2.7% (n = 3) had both fresh and old food remains. Among the plant species exploited with stone tools, fruits of Cnidoscolus quercifolius (faveleira, n = 85; 77.3%) and fruits of exotic Prunus dulcis (almonds, n = 25; 22.7%) had the highest number of food remains.

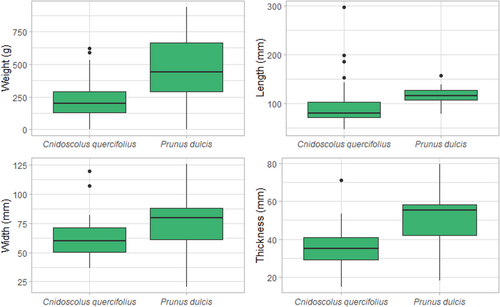

The mean values for the dimensions (weight, length, width, and thickness, respectively) of hammerstones used to process P. dulcis fruits were 467 g (± SD 311), 116 mm (± SD 20), 77 mm (± SD 23), and 50 mm (± SD 16). In the case of C. quercifolius, the mean values of the dimensions recorded were 231 g (± SD 154), 97 mm (± SD 47), 62 mm (± SD 18), and 36 mm (± SD 10). In regard to anvils, the mean width and length of those utilized for processing P. dulcis were 91 cm (± SD 49) and 125 cm (± SD 126), respectively. For C. quercifolius, the mean width and length of the anvils were 64 cm (± SD 53) and 51 cm (± SD 37), respectively. The GLMs comparing the dimensions of the hammerstones used to crack the two most exploited encased foods demonstrated a significant effect on weight, width, and thickness. Thus, the hammerstones used to process P. dulcis fruits were significantly larger than those used for C. quercifolius (Table 3 and Figure 3).

| Dependent variable | Effect | Estimate | Chi-square | df | p value* | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Intercept | 0.004 | 9.611 | 63 | 0.001 | 0.09 |

| Encased-food | −0.002 | −4.354 | 0.001 | |||

| Length | Intercept | 0.0102 | 15.888 | 0.001 | 0.06 | |

| Encased-food | −0.0015 | −1.748 | 0.085 | |||

| Width | Intercept | 0.0160 | 22.189 | 0.001 | 0.11 | |

| Encased-food | −0.0031 | −2.895 | 0.005 | |||

| Thickness | Intercept | 0.0281 | 21.606 | 0.001 | 0.23 | |

| Encased-food | −0.0082 | −4.583 | 0.001 |

5 Discussion

Our study identified the stone tool use sites of blond capuchins in a Caatinga environment in northeastern Brazil and provided the first systematic database of this behavior for this threatened primate species. Most of the food remains found at the processing sites were old, and only two plant species - P. dulcis and C. quercifolius - had encased food that was frequently cracked. Finally, the dimensions (width and thickness) and weight of the hammerstone used to crack P. dulcis-encased food were greater than those of C. quercifolius. Unfortunately, it is not possible to compare our results with other studies of blond capuchin monkeys in both the Atlantic Forest and the Caatinga. However, a robust and reliable comparison can be made with studies focusing on the congeneric species, the bearded capuchin monkeys.

The dimensions of the anvils utilized by the blonde capuchin monkeys in the study area exhibited a comparable length to those observed in other species. However, the width of the anvils was found to be greater (Supporting Information S1: Supplemental Material I). The weight of the hammerstones is consistent with the range observed in other species. For example, the bearded capuchin population at Serra da Capivara National Park utilized hammers with a mean mass of 202 g. Conversely, in the Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park, the hammerstones employed by bearded capuchin monkeys had a mean mass of 1672 g (Supporting Information S1: Supplemental Material I). With regard to the dimensions of the remaining hammerstones (length, width, thickness), the mean values recorded in the study area fall within the range observed for the genus as a whole. The characteristics of the anvils and hammerstones utilized by these primates are intrinsic aspects of each study area. The type of encased food processed, hardness, presence or absence of irritating stings, geomorphology of the region, and study period (rich or lean period of food availability) can exert a significant influence on this variable. Consequently, it is essential to conduct further research and analysis in other areas, specifically those that differ from the study area, to enhance the accuracy and precision of the mean values recorded in this study.

Following the typical pattern of stone tool use sites in capuchin monkeys (see Falótico et al. 2024), blond capuchin monkey tool sites were characterized by the presence of a hammerstone on the broad anvils. This kind of site persists in the environment, thus affording opportunities for practice and learning for naive individuals, in line with the niche theory (Laland, Odling-Smee, and Feldman 2000). Stable anvil sites probably contribute to the maintenance of using stone hammers as a tradition in this group of blonde capuchin monkeys.

We noticed a difference in the majority (customary) of plant species identified and exploited by blond capuchin monkeys at the processing sites compared to other studies. Even with a wide distribution range of C. quercifolius throughout the Caatinga in northeastern Brazil (Maya-Lastra et al. 2024), it was only highly exploited by the blonde capuchins at this site. Similarly, the exotic P. dulcis fruits were only cracked and ingested in this study. Although both blonde and bearded capuchin monkeys live in the Caatinga, the floristic and fruit diversity available at the sites appears to be a factor in the usual cracking in these areas. For example, bearded capuchin monkeys in Serra da Capivara showed a preference for Anacardium sp. nuts and Hymenaea sp. fruits (Falótico and Ottoni 2016). In the Caatinga-Cerrado ecotone at Fazenda Boa Vista, Visalberghi et al. (2008, 2016) verified that the habitual consumption of Attalea barreirensis and Anacardium sp. was common. Also, Mendes et al. (2015) recorded the highest number of Syagrus oleracea cracked by bearded capuchin monkeys at Fazenda São Judas Tadeu, in the northern region of Goiás. Finally, Falótico et al. (2024) found that individuals of bearded capuchin monkeys inhabiting the Parque Nacional de Ubajara habitually cracked and exploited nuts from Acrocomia aculeata and Attalea speciosa. Our study area is characterized as a Caatinga scrubland, with a low number and spacing of trees (unconnected canopy), a high density of shrubs, and without the presence of palm trees (i.e., Syagrus and Attalea) (J.P. Souza-Alves, pers. comm.). Thus, it is likely that habitat-specific conditions, such as floristic composition, are a driver of what capuchins must crack and exploit in these areas.

Exotic plant species are characterized by bearing fruit throughout the year to facilitate seed dispersal and avoid competition with native species (Wolkovich and Cleland 2011). The consumption of exotic plant species by primates has been widely documented in the literature (see Oliveira-Silva et al. 2018; Medeiros et al. 2019; Wimberger, Nowak, and Hill 2017; Eppley et al. 2017). To date, only the exotic cashew nut (Falótico et al. 2017; Visalberghi et al. 2021) has been cracked by bearded capuchin monkeys (Falótico et al. 2022). Exotic plants play a key role in the diet of native and exotic primate species (Oliveira-Silva et al. 2018; Lins and Ferreira 2019; Medeiros et al. 2019). In this study, the consumption of P. dulcis fruits usually occurred during the dry season. The seeds of this plant species are considered to be of high quality due to the high concentration of proteins, minerals, and vitamins (Tomishima, Luo, and Mitchell 2022). Although a systematic and seasonal evaluation is needed, the consumption of P. dulcis fruits seems to favor energy acquisition during the driest and hottest period for blond capuchin monkeys.

Several studies have demonstrated differences in the stone tools used to crack encased foods. For example, the stones used to crack A. aculeata nuts were longer than those used for A. speciosa (Falótico et al. 2024). According to Ferreira, Emidio and Jerusalinsky (2010), hammers used to crack Attalea nuts are almost twice as heavy as those used for Syagrus, and hammers used for Manihot are lighter than those used for the other two resources. In this study, we verified that the stones used to crack the P. dulcis fruits were larger and heavier than those used to crack the C. quercifolius fruits. The main hypothesis to explain this difference is the hardness of the nuts. Heavier hammerstones were usually used to crack harder nuts (Spagnoletti et al. 2011; Visalberghi et al. 2007, 2008). We do not yet have data on the resistance to fracture of the two species of fruits cracked most often by the monkeys in this study. Future studies related to the relationship between hammerstone weight and fruit resistance are in development.

It is not yet possible to suggest that the survival of the blonde capuchin monkeys in the Caatinga is associated with the use of stone tools to access encased foods. In Atlantic Forest fragments, groups of blonde capuchin monkeys exploit a variety of food resources, including fleshy fruits, leaves, seeds, invertebrates, and vertebrates (Lins and Ferreira 2019; Medeiros et al. 2019). Additionally, bearded capuchin monkeys have ingested encased food throughout the use of stone tools, as well as other food items that do not require processing (dos Santos 2015). Therefore, it is feasible that the blonde capuchin monkey group can exploit other foods to maintain the group. However, the high frequency of consumption of exotic almonds (P. dulcis) by the studied blonde capuchin monkeys can support the nutritional capacity of the species during a drought period.

6 Conclusion

This study provides the first comprehensive data on cracking sites and type, and condition of the food items cracked by the Endangered blond capuchin monkeys inhabiting an area of the Caatinga. Here it was possible to understand that the behavioral pattern observed for the species is similar to another capuchin species, even though the study area is located at 532 km of distance (Lima et al. 2024). Similar to other populations of Sapajus, the observed pattern of processing sites should contribute to the maintenance of stone tool use in this primate. A novel aspect appears to be the strong influence of habitat characteristics on the plant species cracked by blond capuchins. Habitat analysis as well as niche and habitat modeling of these plant species need to be implemented in these studies to understand the distribution pattern of these species in the Caatinga biome and their potential driver on the cracked food. Furthermore, we presented a preliminary list of plant species ingested with and without stone tools, highlighting the high rate of the exotic P. dulcis. In addition to the previous knowledge of the plant species used by this primate, such a record should contribute to specific actions for the conservation of these plant species aimed at reducing the potential negative effects on the diet of blond capuchin monkeys. Finally, our study presents a baseline for the development of conservation actions for the species, habitat, and behavior through monitoring of these sites for the manager of the protected area, reducing the logging of plant species cracked, and carrying out environmental activities with the local community to demonstrate the importance of this cycle (primate - habitat - culture).

Author Contributions

Maria Gabriella Rufino: conceptualization (equal), investigation (equal), project administration (equal), writing–original draft (equal). José Jucimário da Silva: investigation (equal). João Pedro Souza-Alves: conceptualization (equal), funding acquisition (equal), methodology (equal), supervision (equal), writing–original draft (equal).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Instituto SOS Caatinga, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Sr. Afonso Oliveira for the logistic support of this research. We are thankful to Camila Chagas for the identification of some plant species. M.G.R. is supported by FACEPE (Grant # 0095-2.04/23). This project is supported by Re:Wild (Process No. CCO-0000000342). We also are grateful to an anonymous reviewer and the Review Editor, Dr. Pedro Dias for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.