The Pediatric Integrated Care Survey (PICS) in a multidisciplinary clinic for Down syndrome

Abstract

The Pediatric Integrated Care Survey (PICS) is validated for use to measure the caregiver reported experience of integration and efficiency of all the aspects of their child. We began using the PICS survey to track changes in the patient experience, including throughout changing models of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. From February 2019 to June 2023, 62 responses from caregivers of individuals seen in the Massachusetts General Hospital Down Syndrome Program completed the PICS. Responses were scored using the standardized PICS user manual, and descriptive statistics were completed. The raw scores and composite monthly scores of the PICs were graphed in statistical process control charts. The average PICS score was 12.0 (range 2–19) out of a maximum score of 19; no shifts or trends were seen. Items with lowest scores indicated greatest opportunities for improvement related to: advice from other care team members, impact of decisions on the whole family, things causing stress or making it hard because of child's health, and offering opportunities to connect with other families. Studying the PICS in a specialty clinic for Down syndrome for the first time has established a baseline for future quality improvement work and interventions to increase care integration.

1 INTRODUCTION

The integrated care model originated in the time of the ancient Greeks who acknowledged the need to treat a patient's mental health in conjunction with their physical health (Kleisiaris et al., 2014). More modern models of integrated care have been seen since the 1970s primarily for child/adolescent health and long-term geriatric care (Goodwin et al., 2021). The PHC (Primary Health Care) movement by the World Health Organization in 1978 focused on improving the “four C's” of primary care: accessible contact; service coordination; comprehensiveness; and continuity of care (Jimenez et al., 2021). These are all fundamental aspects to integrated care (Amelung et al., 2021). Now, we see integrated care clinic models which treat everyone from chronically ill adults to children with fetal alcohol syndrome and congenital disorders (Turchi et al., 2018).

Proper care coordination with multispecialty and primary care providers has been shown to be necessary to improve the quality of pediatric healthcare in the United States (Antonelli & Turchi,2009). Continuous goal setting, planning, monitoring, and assessment were vital to develop and sustain high performance integrated care models in pediatric settings (McAllister et al., 2009). The Pediatric Integrated Care Survey (PICS) was developed by Boston Children's Hospital and Lucile Packard Foundation for Children's Health as a tool for measuring patient and family experience outcomes at integrated care clinics (Ziniel et al., 2015). The PICS was developed and validated using responses from caregivers of children and youth with special health care needs (Ziniel et al., 2015).

The Massachusetts General Hospital Down Syndrome Program (MGH DSP) provides comprehensive care from a physician, social worker, nutritionist, among others to individuals with Down syndrome (DS) in the New England area. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, there were significant changes in the way medical care is provided especially in the use of telemedicine (McMichael et al., 2020) and the MGH DSP was no different (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021). We began this study to assess caregiver-reported views of the integration of care in a multidisciplinary clinic for DS by studying the use of PICS in the MGH DSP. In March 2020, as cases increased in Massachusetts and our hospital system responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, the MGH DSP transitioned quickly to a fully virtual clinic (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021). We hoped to assess care coordination during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the PICS survey has been utilized translated into German-language in a clinic supporting children with chronic illness, the PICS survey has not been utilized in any genetic speciality clinics to our knowledge, including DS clinics (Willems et al., 2022). In the future, this information would help to establish our clinic's baseline PICS score for use in future improvement work, and for other clinics to capture the experience of care integration.

2 METHODS

2.1 The setting

The MGH DSP provides comprehensive care to over 700 unique patients with DS. The MGH DSP provides care for infants, children, adolescents, and adults with DS as well as prenatal consultation for expectant parents. The MGH DSP has distinct clinics by age group with specific clinic days allocated to a given age range. On average, at least 10 clinic visits occurred each week. The multidisciplinary clinic included the following team members: physician, social worker, nutritionist, speech therapist, occupational therapist, physical therapist, psychiatrist, psychologist, neuropsychologist, an educational advocate, a resource specialist, program manager, and others. Specialists from Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital for Children, and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary work together to provide care for people with DS. Our team previously communicated with families electronically through e-mail, the electronic health record, and electronically obtained caregiver feedback. From March 2020 to July 2021, the MGH DSP transitioned to a virtual clinic model (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021). Prior to and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the MGH DSP provided in-person specialty care.

2.2 The PICS instrument

The PICS is a validated tool that explores the diverse needs of each patient as reported by parents. It is intended to measure the experience of care integration, and was originally aimed to allow family/caregivers to determine who conducts the integration. Integrated care entails coordination of medical, behavioral, and social services to holistically accommodate the needs of complex patients. The original validation of the PICS was completed by 255 parents with children 18 and younger (Ziniel et al., 2015). The Core PICS Instrument is a set of 19 validated rating questions that assess a practice's efficacy for integrated care across five factors: access to care, care goal creation/planning, family impact, communication between health care provider and parent, and team functioning and connectivity. Three items are answered using a “yes” or “no” response while 16 items are answered using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always.”

2.3 PICS implementation

With permission from RC Antonelli ([email protected]), from February 2019 to August 2022, the PICS was added to an optional, electronic post-clinic survey which all parents were sent following a visit to the MGH DSP. Caregivers completed the survey on their own personal electronic devices after virtual telehealth visits; therefore, responses could have been collected anytime within the timeframe listed. Caregivers were not reimbursed for completing this survey.

2.4 PICS scoring

Items were eligible to be scored if they were answered by checking a single response option on the scale; if respondents checked none or more than one response, the item is ineligible for scoring. Scoring can be done based on top box or top-2 box scores, and in our study we used top-2 box scoring, such as: positively phrased responses with either “always” or “almost always” responses were scored as “1,” while other responses were scored as “0,” and negatively phrased responses with “never” or “rarely” responses were scored as “1,” while others were scored as “0.” The sum of scores to these 19 items were summed to calculate a total raw score which can range from 0 to 19. Higher scores indicate a greater level of care integration as perceived by the responding caregiver.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, frequencies, and ranges of total raw PICS score, responses to specific PICS item stems, and monthly composite PICS scores were calculated.

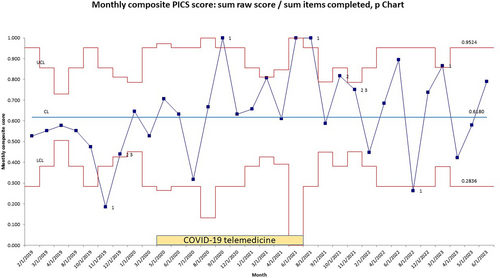

To capture care integration per month, we developed a monthly composite PICS score. The monthly composite PICS score was a fraction of the maximum score that could be received in a month; this was calculated by summing all raw scores for a given month and dividing by the total number of answered responses. For example, in March 2019, two 19-item PICS surveys were completed with scores of 6 and 15; the numerator in March 2019 was 21 and the denominator in March 2019 was 38. Thus, the monthly composite score can range from 0 and 1. Scores closer to 1 indicate a greater level of caregiver-perceived integration.

We plotted P charts using software from a local quality improvement course (Rao et al., 2017) to analyze monthly composite PICS scores. Centerline shifts were determined using standard statistical process control chart rules (Langley et al., 2009; Provost & Murray,2011). We used the American Society for Quality (ASQ) rules to detect special cause variation on charts (ASQ,2019; Tague,2005). Final charts were reviewed by quality improvement course faculty (Rao et al., 2017).

3 RESULTS

- In the past 12 months, how often did you feel that your child's care team members knew about the advice you got from your child's other care team members? (Team Functioning and Connectivity)

- In the past 12 months, how often have your child's care team members talked with you about how health care decisions for your child will affect your whole family? (Family Impact)

- In the past 12 months, how often have your child's care team members talked with you about things in your life that cause you stress because of your child's health or care needs? (Family Impact)

- In the past 12 months, how often have your child's care team members talked to you about things that make it hard for you to take care of your child's health? (Family Impact)

- In the past 12 months, how often have your child's care team members offered you opportunities to connect with other families who they thought might be of help to you? (Family Impact)

| Demographic trait | Number of individuals, N (%) | Mean PICS score |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 0–5 | 15 (24) | 12.35 |

| 6–10 | 7 (11) | 12.73 |

| 11–15 | 9 (15) | 10.64 |

| 16–20 | 6 (10) | 10.83 |

| 21–30 | 12 (19) | 12.73 |

| 31–40 | 9 (15) | 11.4 |

| 41–50 | 4 (6) | 12.73 |

| Race | ||

| White | 52 (84) | 11.4 |

| Black or African American | 2 (3) | 11.59 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (2) | 11.97 |

| Other | 3 (5) | 15.58 |

| Blank | 4 (6) | 16.15 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish | 55 (89) | 11.59 |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish | 3 (5) | 11.97 |

| Blank | 4 (6) | 16.15 |

| Insurance | ||

| Private/Commercial Insurance | 37 (60) | 11.78 |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 22 (35) | 11.59 |

| Blank | 3 (5) | 16.91 |

- Abbreviation: PICS, Pediatric Integrated Care Survey.

| Question | Response option (N, %) | Left blank (N, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the past 12 months, … | Yes | No | |

| did all of your child's medical providers have access to the same medical records? | 42 (68)a | 18 (29) | 2 (3) |

| have your child's care teamb members created short-term care goals, meaning goals up to 6 months in the future? | 42 (68) | 16 (26) | 4 (6) |

| have your child's care team members created long-term care goals, meaning goals 6 months or longer into the future? | 39 (63) | 19 (31) | 4 (6) |

| Question | Response option (N, %) | Left blank (N, %) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the past 12 months, … | Always | Almost always | Usually | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | I do not know | |

| how often did you feel comfortable letting your child's care team members know that you had any concerns about your child's health or care? | 49 (79) | 4 (6) | 5 (8) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (3) |

| how often have your child's care team members treated you as a full partner in the care of your child? | 45 (73) | 6 (10) | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (5) |

| how often did you have difficulties or delays getting medical or social services for your child because you had trouble getting the information you needed?c | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 4 (6) | 12 (19) | 44 (71) | 0 | 0 |

| how often did your child's care team members explain things in a way that you could understand? | 39 (63) | 14 (23) | 8 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| how often did you feel that your child's care team members listened carefully to what you had to say about your child's health and care? | 33 (53) | 18 (29) | 4 (6) | 4 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (5) |

| how often did you feel that your child's care team members were aware of all tests and evaluations your child has had recently in order to avoid unnecessary testing? | 32 (52) | 11 (18) | 7 (11) | 6 (10) | 0 | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| how often did you feel that your child's care team members followed through with their responsibilities related to your child's care? | 32 (60) | 11 (21) | 5 (9) | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| how often did you have difficulties or delays getting medical or social services for your child because there were waiting lists, backlogs, or other problems getting appointments?c | 0 | 1 (2) | 4 (6) | 14 (23) | 15 (24) | 28 (45) | 0 | 0 |

| how often have you felt that your child's care team members thought about the “big picture” when caring for your child, meaning dealing with all of your child's needs? | 24 (39) | 14 (23) | 11 (18) | 5 (8) | 5 (8) | 0 | 0 | 3 (5) |

| how often has someone on your child's care team explained to you who was responsible for different parts of your child's care? | 24 (39) | 13 (21) | 8 (13) | 6 (10) | 4 (6) | 5 (8) | 0 | 2 (3) |

| how often have your child's care team members talked with you about how health care decisions for your child will affect your whole family? | 18 (29) | 6 (10) | 6 (10) | 8 (13) | 12 (19) | 9 (15) | 0 | 3 (5) |

| how often have your child's care team members offered to communicate with you in ways other than an in-person visit, such as phone, email, skype, or telehealth, if no physical examination was necessary? | 14 (24) | 8 (14) | 13 (22) | 11 (19) | 4 (7) | 9 (15) | 0 | 0 |

| how often did you feel that your child's care team members knew about the advice you got from your child's other care team members? | 14 (23) | 14 (23) | 17 (27) | 11 (18) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (3) |

| how often have your child's care team members talked with you about things in your life that cause you stress because of your child's health or care needs? | 13 (21) | 1 (2) | 4 (6) | 12 (19) | 12 (19) | 17 (27) | 0 | 3 (5) |

| how often have your child's care team members talked to you about things that make it hard for you to take care of your child's health? | 9 (15) | 0 | 5 (8) | 10 (16) | 16 (26) | 18 (29) | 0 | 4 (6) |

| how often have your child's care team members offered you opportunities to connect with other families who they thought might be of help to you? | 9 (15) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 14 (23) | 10 (16) | 22 (35) | 0 | 3 (5) |

- Note: Bold items are the five lowest-scoring questions.

- Abbreviation: PICS, Pediatric Integrated Care Survey.

- a Green = most common known response; orange = least common known response.

- b For questions about “care team,” the text “The following questions refer to your child's ‘care team.’ When answering these questions, please consider all types of health care providers that you consider to be part of your child's care team.” was provided.

- c Questions with italic text have negative wording, those without italic text have positive wording.

Four of these questions assessed the construct of family impact, and one assessed team connectivity. The responses of these five lowest-scoring questions by year showed spread across the 6-scale Likert response options (Table 3).

| Question | Response options | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the past 12 months, … | Year | Always | Almost always | Usually | Sometimes | Rarely | Never |

| how often did you feel that your child's care team members knew about the advice you got from your child's other care team members? | 2019 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 2020 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2021 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2022 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2023 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| how often have your child's care team members talked with you about how health care decisions for your child will affect your whole family? | 2019 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| 2020 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 2021 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 2 | |

| 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| 2023 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| how often have your child's care team members talked with you about things in your life that cause you stress because of your child's health or care needs? | 2019 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| 2020 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2021 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | |

| 2022 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| 2023 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| how often have your child's care team members talked to you about things that make it hard for you to take care of your child's health? | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| 2020 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2021 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| 2022 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| 2023 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| how often have your child's care team members offered you opportunities to connect with other families who they thought might be of help to you? | 2019 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 7 |

| 2020 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 2021 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |

| 2022 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| 2023 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

- Abbreviation: PICS, Pediatric Integrated Care Survey.

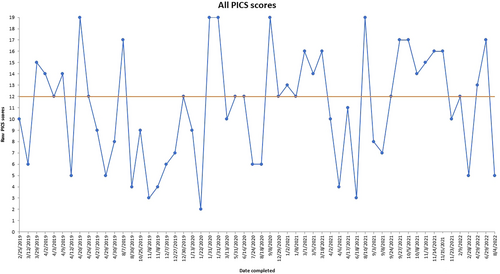

Over time, the average raw PICS score for all respondents was 12 out of 19 possible and was stable (Figure 1). Median monthly composite PICS score was 0.618 equating to a raw PICS score of 11.7 (0.618 × 19) and ranged from 0.1 to 1.0 (Figure 2). P charts of monthly composite PICS scores (Figure 2) illustrated one stable process stage. From September 1, 2020 to August 1, 2021, 7 of 8 points were above the centerline, but this did not meet rules for special cause. No trends or shifts in data were seen in monthly composite PICS score during the COVID-19 pandemic when the MGH DSP conducted virtual telemedicine visits from April 1, 2020 to June 1, 2021.

4 DISCUSSION

Multidisciplinary DS clinics exist across the county (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021), to address a variety of caregivers' concerns (Cabrera et al., 2022) through diverse models including collaboration with primary care physicians or serving as a medical home. In the MGH DSP, we follow a collaborative, subspecialist model and our multidisciplinary team plays roles in healthcare maintenance, nutrition counseling, behavior and mental health screening, and care coordination. As such, a key component of our program is providing comprehensive, integrated, team-based care annually, and we surveyed caregivers to assess the degree of care integration.

Using the PICS in a multidisciplinary DS specialty clinic for the first time, caregivers in the MGH DSP rated our clinic's experience of care integration at an average raw score of 12 out of maximum 19 points on the PICS. Without special cause in our data over time, we have established a baseline raw PICS score in our clinic cohort. This has utility for our specific clinic cohort as we can now begin to implement interventions to improve the experience of care integration as perceived by caregivers. Although the PICS has been used as an outcome in other intervention projects (Gall et al., 2022), and has been validated in a German cohort using a 13-item form (Willems et al., 2022), population-based norms are not yet available to determine how well the experience of our clinic's care integration compares to other practices.

Additionally, analyzing specific items allowed us to identify areas of relative strength and weakness to be able to guide our interventions to target specific constructs of care integration. For example, in the five specific PICS items that showed the greatest need for improvement, four items were related to family impact. This suggests that there is a need for the care team to improve communication of support systems for families and assessing caregiver stress. The MGH DSP has a number of community partners, including the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress and the Down Syndrome Autism Connection, which provide parent-to-parent connection. Additionally, for patients with unique presentations, such as Down Syndrome Regression Disorder (Santoro et al., 2022; Santoro et al., 2020), or considering specific treatments, such as hypoglossal nerve stimulator (Stenerson et al., 2021), we often make direct connections. Our team could consider ways to consistently communicate support for all families, and directly name that step when discussing with parents. For example, a clinician might state that they are placing a referral to the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress and that “this referral is for family to family connection.” This support, connection, and caregiver stress were not routinely identified as a “top concern” that caregivers would like to address in our previous QI project (Cabrera et al., 2022). Rather, caregivers identified that the top reasons for visiting the MGH DSP were related to health maintenance, establishing patient care and preventative measures, behavior, and neurologic considerations, including regression and dementia (Cabrera et al., 2022).

Our experience in establishing baseline raw PICS scores and lowest scoring specific items may provide useful information to other DS specialty clinics and suggest potential areas for future quality improvement. Our study shows that the PICS can be implemented in a DS specialty clinic. Though, as clinic models vary (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021), other DS clinics could use the PICS to compare findings to ours and to identify aspects of the experience of care integration through the PICS which are specific to their clinic. Additionally, multidisciplinary specialty clinics for other genetic syndromes could follow our approach to use the PICS in their clinic population to assess care integration and clinic model.

Our PICS responses were collected, in part, during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results from this study provide insights into family and caregiver experiences in the MGH DSP during that unique time. We previously tracked patient satisfaction and administrative outcomes during our transition to virtual visits and telemedicine (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021), but this study is the first to use a validated measure of care integration PICS tool to examine patient and caregiver experience of care integration in the DS community. We hypothesized that the experience of care integration, and PICS scores, might worsen due to the multiple demands placed on families, the MGH DSP, and the hospital system. However, we were pleased to see that PICS scores did not significantly decrease during the time of virtual visits, and actually saw that some of our highest PICS scores were reported during that time. This likely reflects on the high level of effort by our team to maintain and increase communication with patients and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. This stability could be due to virtual visits improving accessibility to care and offsetting barriers due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We chose an electronic mode of administration and recruited caregivers from our clinic cohort through email as the pilot study of the PICS used email and mail to administer the survey. However, it is important to note that the survey had to be taken on personal devices after telehealth visits. Thus, it is likely that only families with access to personal devices were able to complete the survey.

The MGH DSP follows patients with DS throughout the lifespan. The PICS was originally validated for caregivers of children with special health care needs age 18 or younger, and care integration measures exist to assess coordinated care in the chronically ill adult patients (Singer et al., 2013). Some of our cohort were older than 18, and not in the age for which the PICS is validated. However, for consistency across our clinic, we opted to choose one measure of care integration rather than multiple instruments. This allowed us to more easily track the experience of our clinic's care integration over time and attribute changes seen, if any, to clinic changes rather than to differences in the measurement tool used.

Additional limitations include that this is a single site quality improvement project, and may not generalize to other clinics for DS, to the population with DS in the United States, and to other multidisciplinary clinics for other genetic conditions. Additionally, as the PICS survey was an optional section within an optional after-visit survey, our response rate was low with 62 PICS survey responses out of a total of 700 patients. We hypothesize that those completing the after-visit survey may have strong opinions, either strongly positive or strongly negative, and be more likely to take the time to complete the optional, non-reimbursed survey to share those views. Due to the option of respondents to report name, we are not able to determine if a caregiver filled out the survey more than once. We also acknowledge that the initial after clinic survey, prior to adding PICS questions in, only included 5 questions; therefore, it is possible caregivers were overwhelmed at the increase in number of questions and chose to skip this optional step. We unfortunately were unable to assess how much time individuals took on the survey. In the future, we would like to continue to find ways to collect views from a broader cohort of our clinic population, encourage participation, and gather data on the time burden of this survey. We hope to also add a question to confirm the caregiver had not filled out the survey before, but not removing the option to remain anonymous (i.e., “Have you completed this survey before?”).

One final limitation that is crucial to address is the lack of diversity within the patient population: the majority of the population surveyed is White and non-Hispanic (Table 1) thus excluding some of the DS population. As previous research has addressed, unconscious and conscious racial bias can be a barrier to care for patients (Krell et al., 2023); therefore, in the future, we hope to work to broaden our research community base and extend this research to more clinics in order to make the findings more generalizable.

Overall, the results of this survey provide important insights into patient and family experiences with care teams and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these experiences. Healthcare providers can use these findings to improve communication and support for families, particularly in the context of stressful situations related to their child's health, and consider the continued use of virtual visits as a potential option for improving patient and family experiences.

5 CONCLUSION

Care integration is a gap which multidisciplinary clinics can fill in conjunction with primary care physicians. Beginning to measure the experience of care integration through valid tools, like the PICS, is the first step to begin work to improvement. Family support, parent-to-parent connection, and caregiver stress were identified as areas for future efforts.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors confirm that this manuscript has not been published previously and is not under consideration elsewhere, that all authors are responsible for reported research, and that all authors have participated in the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting or revising of the manuscript, and have read and approved the submission to the journal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Appreciation is given to the patients and families in the MGH DSP for their participation in this, and other research projects.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Santoro receives research funding from the LuMind IDSC Down Syndrome Foundation to conduct clinical trials for people with DS and serves on the Executive Board for the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress, the Board of the Down Syndrome Medical Interest Group, and the Executive Board of the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Genetics. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The anonymized, de-identified data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.