Kabuki make-up syndrome: A review

Abstract

Kabuki make-up syndrome (KMS, OMIM 147920) is an MCA/MR syndrome of unknown cause. It is characterized by a dysmorphic face, postnatal growth retardation, skeletal abnormalities, mental retardation, and unusual dermatoglyphic patterns. Approximately more than 350 cases have been reported from all over the world. Besides these five cardinal manifestations, joint laxity (74%), dental abnormalities (68%), and susceptibility to infections including recurrent otitis media (63%) were well recognized as other frequent features. A variety of visceral anomalies such as caidiovascular anomalies (42%), renal and/or urinary tract anomalies (28%), biliary atresia, diaphragmatic hernia, and anorectal anomaly were also reported. Some patients were said to have normal intelligence (16%) and normal heights, suggesting that they may have reproductive fitness to have their children. At least eight patients had lower lip pits with or without cleft palate, known as a feature of van der Woude syndrome. There have been 13 chromosomal abnormalities associated with KMS. However, no common abnormalities or breakpoints that possibly contribute to positional cloning of the putative KMS gene(s) are known. Although clinical manifestations of KMS are well established, its natural history, useful for genetic counseling, remains to be studied. © 2003 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Kabuki make-up syndrome (KMS, OMIM 147920) is a multiple congenital anomalies/mental retardation (MCA/MR) syndrome of unknown cause. It is characterized by a peculiar facial appearance, mild to moderate mental retardation, postnatal growth retardation, skeletal anomalies, and unusual dermatoglyphic patterns [Niikawa et al., 1988]. KMS was first described independently by two groups from Japan [Kuroki et al., 1981; Niikawa et al., 1981]. KMS was thought not to be fairly common outside of Japan, but it is now well recognized all over the world.

KMS was thought not to be fairly common outside of Japan, but it is now well recognized all over the world.

More than 350 cases are known in the literature [see Table I], and several additional manifestations were recognized to be characteristic and diagnostic of KMS. However, there have not yet been any clues toward the cause of the syndrome. In this paper, currently recognized clinical findings of KMS with some research aspects are reviewed.

| Clinical findings | The number (the total number) of patients reported by | Sum of patients | % | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Niikawa et al. [1988] |

Philip et al. [1992] |

Schrander-Stumpel et al. [1994] |

Hughes and Davies [1994] |

Galan-Gomez et al. [1995] |

Ilyina et al. [1995] |

Wilson [1998] |

Mhanni et al. [1999] |

Kawame et al. [1999] |

Kluijt et al. [2000] |

McGaughran et al. [2001] |

Digilio et al. [2001] |

Shotelersuk et al. [2002] |

|||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 31 (62) | 9 (16) | 16 (29) | 6 (14) | 2 (5) | 5 (5) | 8 (13) | 2 (8) | 8 (18) | 3 (6) | 4 (9) | 37 (60) | 4 (6) | 135 (251) | 54 |

| Craniofacial abnormality | |||||||||||||||

| Characteristic face | 62 (62) | 29 (29) | 10 (10) | 8 (8) | 6 (6) | 115 (115) | 100 | ||||||||

| Microcephaly | 3 (51) | 7 (16) | 9 (29) | 3 (10) | 8 (13) | 17 (60) | 47 (179) | 26 | |||||||

| Long palpebral fissure | 16 (16) | 29 (29) | 10 (10) | 12 (13) | 8 (8) | 60 (60) | 135 (136) | 99 | |||||||

| Epicanthus | 35 (57) | 8 (16) | 5 (5) | 15 (60) | 63 (138) | 46 | |||||||||

| Lower palpebral eversion | 61 (62) | 15 (16) | 24 (29) | 5 (5) | 10 (10) | 10 (13) | 7 (8) | 132 (143) | 92 | ||||||

| Ptosis | 6 (15) | 12 (13) | 4 (18) | 4 (6) | 26 (52) | 50 | |||||||||

| Strabismus | 21 (43) | 5 (15) | 2 (5) | 4 (10) | 3 (13) | 3 (6) | 16 (60) | 54 (152) | 36 | ||||||

| Blue sclerae | 14 (52) | 9 (25) | 4 (10) | 6 (13) | 4 (18) | 1 (6) | 38 (124) | 31 | |||||||

| Short nasal septum | 50 (54) | 14 (16) | 8 (8) | 72 (78) | 92 | ||||||||||

| Arched eyebrow | 51 (58) | 15 (16) | 23 (29) | 9 (9) | 9 (13) | 8 (8) | 50 (60) | 165 (193) | 85 | ||||||

| Prominent ear | 51 (60) | 13 (16) | 5 (5) | 10 (10) | 12 (13) | 8 (8) | 46 (60) | 145 (172) | 84 | ||||||

| Preauricular dimple/fistula | 20 (52) | 1 (16) | 4 (25) | 5 (18) | 1 (9) | 9 (60) | 40 (180) | 22 | |||||||

| Depressed nasal tip | 45 (57) | 13 (16) | 23 (29) | 5 (5) | 12 (13) | 8 (8) | 106 (128) | 83 | |||||||

| Malformed ear | 37 (47) | 13 (16) | 29 (29) | 8 (8) | 87 (100) | 87 | |||||||||

| Abnormal dentition | 35 (45) | 10 (13) | 17 (24) | 3 (4) | 6 (9) | 9 (13) | 8 (8) | 28 (55) | 116 (171) | 68 | |||||

| High-arched palate | 24 (38) | 15 (16) | 5 (5) | 7 (13) | 8 (8) | 5 (9) | 64 (89) | 72 | |||||||

| Micrognathia | 20 (55) | 10 (16) | 6 (9) | 1 (13) | 37 (93) | 40 | |||||||||

| Cleft palate/lip and palate/lip | 23 (56) | 20 (29) | 2 (10) | 5 (8) | 6 (18) | 3 (9) | 8 (60) | 1 (6) | 68 (196) | 35 | |||||

| Lower lip pit | 1 (9) | 3 (6) | 4 (15) | 27 | |||||||||||

| Low posterior hair line | 27 (51) | 11 (16) | 38 (67) | 57 | |||||||||||

| Bone abnormality | |||||||||||||||

| Skeletal abnormality | 56 (61) | 22 (27) | 8 (8) | 50 (60) | 6 (6) | 142 (162) | 88 | ||||||||

| Short finger (V) | 47 (53) | 14 (16) | 19 (26) | 2 (5) | 5 (10) | 48 (60) | 135 (170) | 79 | |||||||

| Clinodactyly (V) | 14 (16) | 2 (5) | 7 (10) | 5 (13) | 6 (8) | 22 (60) | 56 (112) | 50 | |||||||

| Short middle phalanx (V) | 35 (44) | 10 (12) | 15 (20) | 60 (76) | 80 | ||||||||||

| Short metacarpal | 10 (39) | 8 (12) | 18 (51) | 35 | |||||||||||

| Cone-shaped epiphysis | 6 (37) | 0 (10) | 6 (47) | 13 | |||||||||||

| Coarse carpal bone | 5 (37) | 3 (11) | 8 (48) | 17 | |||||||||||

| Deformed vertebra/rib | 29 (41) | 3 (60) | 32 (101) | 32 | |||||||||||

| Scoliosis | 26 (53) | 5 (14) | 7 (23) | 2 (5) | 0 (13) | 18 (60) | 58 (168) | 35 | |||||||

| Sagittal cleft of vertebral body | 12 (37) | 3 (13) | 5 (5) | 20 (55) | 36 | ||||||||||

| Rib anomaly | 8 (37) | 1 (13) | 1 (5) | 10 (55) | 18 | ||||||||||

| Spina bifida occulta | 6 (37) | 2 (13) | 3 (9) | 11 (59) | 19 | ||||||||||

| Pilonidal sinus | 5 (6) | 5 (6) | 83 | ||||||||||||

| Hip dislocation | 18 (55) | 3 (16) | 7 (25) | 1 (13) | 2 (9) | 1 (60) | 32 (178) | 18 | |||||||

| Foot deformity | 7 (34) | 3 (16) | 3 (5) | 13 (55) | 24 | ||||||||||

| Dermatoglyphics finding | |||||||||||||||

| Abnormal dermatoglyphic finding | 40 (43) | 28 (28) | 8 (8) | 76 (79) | 96 | ||||||||||

| Presence of fingertip pad | 35 (45) | 28 (28) | 5 (5) | 7 (7) | 13 (13) | 8 (8) | 16 (18) | 52 (60) | 6 (6) | 170 (190) | 89 | ||||

| Neurological abnormality | |||||||||||||||

| Mental retardation (IQ < 80) | 57 (62) | 15 (16) | 5 (5) | 8 (10) | 13 (13) | 5 (7) | 9 (9) | 40 (60) | 5 (6) | 157 (188) | 84 | ||||

| Hypotonia | 7 (16) | 9 (13) | 16 (18) | 32 (47) | 68 | ||||||||||

| Neonatal hypotonicity | 3 (58) | 20 (23) | 23 (81) | 28 | |||||||||||

| Seizure | 9 (58) | 7 (16) | 3 (29) | 0 (13) | 7 (18) | 7 (60) | 33 (194) | 17 | |||||||

| Brain atrophy | 2 (51) | 2 (51) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Retinal pigmentation | 1 (29) | 1 (29) | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Stature | |||||||||||||||

| Short stature (<−2.0 SD) | 30 (41) | 4 (5) | 6 (9) | 9 (13) | 1 (8) | 25 (60) | 75 (136) | 55 | |||||||

| Visceral abnormality | |||||||||||||||

| Hyperpigmented nevus | 12 (55) | 12 (55) | 22 | ||||||||||||

| Generalized hirsutism | 3 (45) | 4 (16) | 7 (61) | 11 | |||||||||||

| Cardiovascular anomaly | 19 (59) | 5 (15) | 8 (29) | 10 (20) | 1 (10) | 6 (13) | 6 (8) | 7 (18) | 4 (9) | 35 (60) | 2 (6) | 103 (247) | 42 | ||

| Umbilical hernia | 4 (51) | 2 (16) | 6 (67) | 9 | |||||||||||

| Kidney/urinary tract malformation | 7 (58) | 7 (16) | 9 (27) | 8 (13) | 6 (18) | 3 (9) | 1 (4) | 41 (145) | 28 | ||||||

| Undescended testis | 5 (20) | 6 (9) | 1 (9) | 6 (37) | 18 (75) | 24 | |||||||||

| Small penis | 2 (20) | 1 (9) | 3 (29) | 10 | |||||||||||

| Malrotation of colon | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 6 | ||||||||||||

| Anal atresia/rectovaginal fistula | 3 (58) | 1 (16) | 4 (74) | 5 | |||||||||||

| Inguinal hernia | 3 (52) | 2 (16) | 5 (68) | 7 | |||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||

| Joint laxity | 10 (16) | 22 (23) | 11 (13) | 6 (8) | 9 (18) | 58 (78) | 74 | ||||||||

| Recurrent otitis media | 30 (55) | 19 (26) | 7 (8) | 13 (18) | 4 (9) | 73 (116) | 63 | ||||||||

| Hearing loss | 13 (55) | 3 (16) | 12 (24) | 1 (4) | 7 (18) | 2 (9) | 10 (54) | 48 (180) | 27 | ||||||

| Early breast development | 7 (31) | 2 (7) | 4 (8) | 13 (46) | 28 | ||||||||||

| Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia | 12 (58) | 2 (13) | 14 (71) | 20 | |||||||||||

| Obesity | 11 (58) | 11 (58) | 19 | ||||||||||||

| Anemia | 5 (56) | 5 (56) | 9 | ||||||||||||

| Polycythemia | 2 (56) | 2 (56) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Neonatal hypoglycemia | 4 (58) | 4 (58) | 7 | ||||||||||||

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 1 (58) | 1 (58) | 2 | ||||||||||||

| GH deficiency | 1 (58) | 1 (58) | 2 | ||||||||||||

| TBG deficiency | 1 (58) | 1 (58) | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 (58) | 1 (58) | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Primary ovarian dysfunction | 1 (58) | 1 (58) | 2 | ||||||||||||

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

On the basis of analysis of 62 patients, Niikawa et al. [1988] summarized clinical findings of KMS by listing the following five cardinal manifestations: 1) peculiar, characteristic face (100%), 2) skeletal abnormality (92%), 3) dermatoglyphic abnormality (93%), 4) mental retardation (92%), and 5) short stature (83%). Although helpful for diagnosis, all these cardinal manifestations-except for a facies are not absolutely contributory to the diagnosis. A summary of manifestations in 13 review reports, each dealing with five or more patients, revealed that skeletal anomalies (142/162, 88%), mental retardation (IQ < 80; 157/188, 84%), and short stature (<–2SD; 75/136, 55%) are less common than estimated previously [Niikawa et al., 1988; Philip et al., 1992; Hughes and Davies, 1994; Schrander-Stumpel et al., 1994; Galan-Gomez et al., 1995; Ilyina et al., 1995; Wilson, 1998; Kawame et al., 1999; Mhanni et al., 1999; Kluijt et al., 2000; Digilio et al., 2001; McGaughran et al., 2001; Shotelersuk et al., 2002] (Table I). Instead, joint laxity (58/78,74 %) is a frequently observed feature that was overlooked in the previous analyses

Instead, joint laxity is a frequently observed feature that was overlooked in the previous analyses.

[Philip et al., 1992; Schrander-Stumpel et al., 1994; Wilson, 1998; Kawame et al., 1999; Mhanni et al., 1999]. Although many additional, unique manifestations have been described, they seem to be observed only in specific cases. Details of some characteristic manifestations are described below.

Craniofacial Anomalies

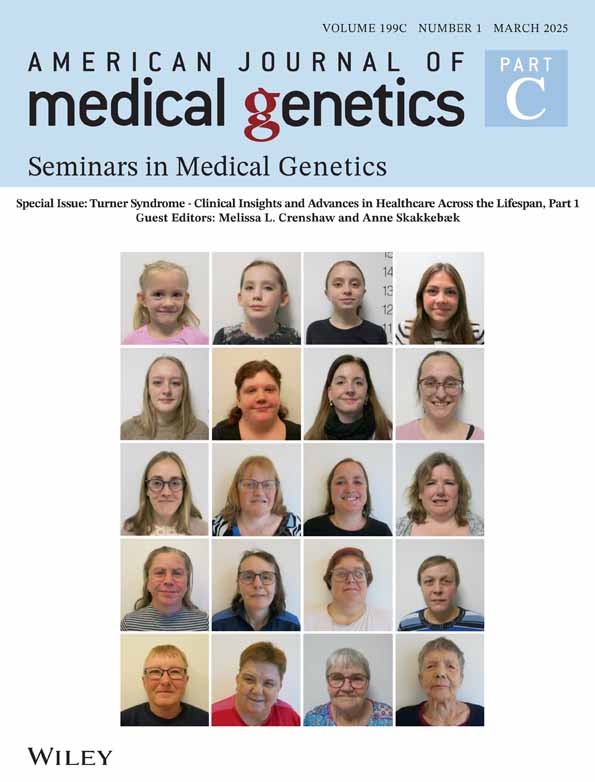

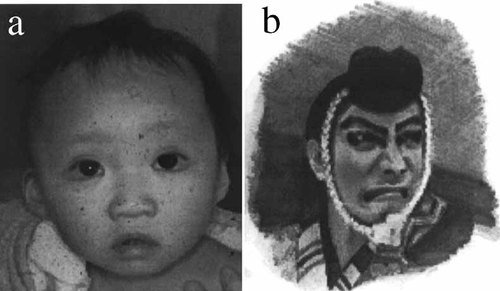

The most striking feature is the peculiar face that consists of eversion of the low lateral eyelid that is reminiscent of a Kabuki actor's makeup (Figs. 1a and 1b), arched eyebrows with sparseness of their lateral one-third, especially seen in most Japanese patients, long palpebral fissures with long eyelashes, depressed nasal tip, and prominent, large ears.

The most striking feature is the peculiar face that consists of eversion of the low lateral eyelid that is reminiscent of a Kabuki actor's makeup, arched eyebrows with sparseness of their lateral one-third, long palpebral fissures, depressed nasal tip, and prominent, large ears.

They are recognized in almost all patients (115/115 in the reviewed reports, 100%). Less frequently observed are strabismus, blue sclerae, high-arched palate (64/89, 72%) or cleft lip/palate (68/196, 35%), a preauricular fistula, and abnormal dentitions (119/171, 68%). Such dental abnormalities included hypodontia, absence of upper lateral and lower central incisors and upper molars, abnormal tooth shape, and widely spaced teeth, occurring probably in both the milk and permanent teeth (Fig. 2) [Mhanni et al., 1999]. At least eight reported patients had lower lip pits [Niikawa et al., 1988; Franceschini et al., 1993; Kokitsu-Nakata et al., 1999; Makita et al., 1999; McGaughran et al., 2001; Shotelersuk et al., 2002]. This anomaly with or without cleft palate is known to be associated with van der Woude syndrome (VWS) [OMIM *119300], and may be a clue to the cause of the syndrome (described later).

Facial appearance of a patient with Kabuki make-up syndrome (a), reminiscent of Kabuki actor's makeup for the Japanese hero warrior, Benkei (b).

A plaster cast for lower teeth with abnormal dentitions.

Skeletal Abnormalities and Hypermobility of Joints

Skeletal abnormalities observed included short fifth fingers, short fifth middle phalanges, variable degrees of scoliosis and/or kyphosis, vertebral body anomalies (typically, sagittal cleft, butterfly vertebrae, hemivertebrae and/or spina bifida occulta), rib anomalies; hip dislocation; and dislocation of the patella (Table I). General hypermobile, loose joints (74%) were frequently observed [Philip et al., 1992; Schrander-Stumpel et al., 1994; Wilson, 1998; Kawame et al., 1999; Mhanni et al., 1999] (Table I). It remains to be investigated whether the joint laxity is neurogenic or due to loose connective tissues.

Unusual Dermatoglyphic Patterns

A combination of unusual dermatoglyphic patterns was frequently observed [Schrander-Stumpel et al., 1994; Mhanni et al., 1999], as pointed out previously [Niikawa et al., 1982, 1988]. The unusual patterns include frequent fingertip ulnar loop patterns, the absence of digital triradius “c” or “d”, an interdigital triradius “bc” or “cd”, and hypothenar loop patterns and ulnar loop patterns in the fourth interdigital area. Another characteristic feature is fingertip pads (170/190 patients, 96%) (Fig. 3), possible remnants of fetal pads [Niikawa et al., 1988]. These features are diagnostic of the syndrome.

Fingertip pads, a feature diagnostic of KMS.

Neurological Findings

Mental retardation is usually mild to moderate. Most such patients can speak and seem to adapt to special school education for mildly handicapped children. However, about one-sixth (31/188, 16%) of patients were said to be of normal intelligence (Table I). This suggests that some of them may have reproductive fitness to have their children. Muscular hypotonicity (32/47, 68%) and/or neonatal hypotonia (23/81, 28%) are evident in many patients, probably related to joint laxity. Seizures (33/194, 17%) (Table I), microcephaly with or without brain atrophy [Niikawa et al., 1988; Yano et al., 1997], polymicrogyria [Di Gennaro et al., 1999], subarachnoid cyst [Chu et al., 1997], and autistic features [Ho and Eaves, 1997] are also occasionally observed.

Growth

Birth weight (3,180 g and 2,943 g for Japanese male and female patients, respectively) and length (49.1 cm for Japanese patients of either gender) are basically within the normal range [Niikawa et al., 1988]. Many patients develop a failure to thrive by the age of three months, and postnatal growth retardation (mostly a –2 SD level) becomes prominent. Final height is expected to be about 152 cm for Japanese patients [Niikawa et al., 1988]. GH deficiency was rarely reported [Niikawa et al., 1988; Tawa et al., 1994; Devriendt et al., 1995]. Early breast development (early thelarche) and/or precocious puberty is occasionally noted, particularly in girls [Kuroki et al., 1987; Franceschini et al., 1993; Tutar et al., 1994; Devriendt et al., 1995; Bereket et al., 2001].

Visceral Anomalies

Cardiovascular defects, including ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, coarctation of aorta, patent ductus arteriosus, and transposition of great vessels have been reported in many patients

Cardiovascular defects, including ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, coarctation of aorta, patent ductus arteriosus, and transposition of great vessels have been reported in many patients.

(103/247, 42%) (Table I). Renal and/or urinary tract anomalies (41/145, 28%) are also frequent. Other visceral abnormalities reported are biliary atresia [McGaughran et al., 2000; van Haelst et al., 2000], diaphragmatic hernia [Donadio et al., 2000; van Haelst et al., 2000], and anorectal anomaly [Matsumura et al., 1992; Kokitsu-Nakata et al., 1999].

Susceptibility to Infections

Recurrent otitis media (73/116, 63 %), upper respiratory tract infections, and/or pneumonia suggest that patients have susceptibility to infections. Although the underlying mechanism is unknown, certain immunodeficiencies may exist. In fact, severe immunodeficiency [Chrzanowska et al., 1998], autoimmune hemolytic anemia and polycytemia [Niikawa et al., 1988], chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenia [Watanabe et al., 1994], and acquired hypogammaglobulinemia with anti-IgA antibody [Hostoffer et al., 1996] were reported in single cases. However, it is also plausible that recurrent otitis media is related to cleft palate, and subsequently leads to conductive hearing impairment [Niikawa et al., 1988].

PREVALENCE/PROGNOSIS/NATURAL HISTORY

Over 350 cases were reported from Asia, the near East, Europe, Australasia, and North and South America. The prevalence of KMS was estimated to be 1/32,000 live births on the basis of data from “Monitoring for Congenital Anomalies” in Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan

The prevalence of KMS was estimated to be 1/32,000 live births on the basis of data from “Monitoring for Congenital Anomalies” in Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan.

[Niikawa et al., 1988]. No other estimates have been reported from other areas. The oldest patient with typical KMS phenotype was 29 yeas old in 1988 [Niikawa et al., 1988] and is 42 if she is alive today; she has not been followed up. Because there are no fatal clinical manifestations, patients may survive with a good prognosis, unless they have severe complications, such as infectious, cardiovascular, hepatic, or renal diseases. Most female patients may have regular menstruation and only few patients have severe mental retardation, so that there is no significant reason for loss of fitness. This may suggest that female patients with normal intelligence or mildly mental retardation are fertile. Fertility for male patients remains unknown, although fathers in four families were said to be affected or to have a facies characteristic of the syndrome [Ilyina et al., 1995; Frediani et al., 2001; Kobayashi et al., 2001]. As a natural history of the syndrome has not been known, it should be studied based on a large series of patients.

GENETICS

The male-to-female ratio among 251 reported patients was 1.16 to 1 (135/116), nearly equal. Most cases are sporadic, but at least 14 familial cases were known. There were seeming direct transmissions of the disease from mother to a daughter in three families [Silengo et al., 1996; Tsukahara et al., 1997], mother to a son in one family [Say et al., 1993], mother to both a girl and a boy in one family [Halal et al., 1989; Frediani et al., 2001], and father to a daughter in one family [Kobayashi and Sakuragawa, 1996]. Thus, it is less likely that genomic imprinting is an underlying mechanism. A facial appearance characteristic of the syndrome was observed in the mother in four families [Ilyina et al., 1995; Wilson, 1998; Courtens et al., 2000; Shotelersuk et al., 2002] as suggested previously by Niikawa et al. [Niikawa et al., 1981, 1988], and in the father in three families [Ilyina et al., 1995; Frediani et al., 2001]. In two pairs of identical twins, one pair was concordant [Lynch et al., 1995] and the other pair discordant for the syndrome [Shotelersuk et al., 2002]. The discordance between the twins suggests the occurrence of a post-zygotic mutation, although multifactoral causes cannot be ruled out. All these findings are not inconsistent with the hypothesis that KMS is an autosomal dominant disorder (OMIM 147920).

A balanced chromosome translocation would be a good source for positional cloning of the disease gene, if two or more aberrations with identical breakpoints were known. About a dozen chromosomal abnormalities have been reported to be associated with KMS (Table II). However, because there were no autosomal abnormalities with identical breakpoints, they may not be contributory to KMS. The sex chromosome abnormalities associated with KMS merit comment. It has repeatedly been pointed out that some manifestations of KMS overlap those of Turner syndrome [Niikawa et al., 1988; Dennis et al., 1993; Wellesley and Slaney, 1994; Abd et al., 1997]. In fact, 45,X cell lines were found in six patients [Niikawa et al., 1988; Wellesley and Slaney, 1994; Moncla et al., 1996; Abd et al., 1997; McGinniss et al., 1997]. Among them, structurally abnormal sex chromosomes with a breakpoint of Xp11 or Yp11 are of great interest. Assuming that the sex ratio among patients is almost one, pseudoautosomal or homologous regions between X and Y chromosomes would be attractive candidate disease loci, as suggested previously [Niikawa et al., 1988]. This hypothesis is becoming testable, as the sequence phase of the human genome project is being completed. Female patients with a small ring X chromosome have been reported [Niikawa et al., 1988; Abd et al., 1997; McGinniss et al., 1997]. Clinical manifestations in these patients were much more severe than those in most KMS patients. Personally speaking, it is most likely that the condition associated with the small ring X chromosome is causally different from KMS.

| Chromosomal abnormalities | References | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal | ||

| der(6)t(6;12)(q25.3;q24.31)mat |

Jardine et al. [1993] |

|

| inv(4)(p12pter)mat |

Fryns et al. [1994] |

|

| t(15;17)mat |

Galan-Gomez et al. [1995] |

|

| psu dic(13) |

Lynch et al. [1995] |

|

| dup(1)(p13.1p22.1) |

Lo et al. [1998] |

|

| t(3;10)(p25;p15) |

Digilio et al. [2001] |

In two sibs |

| Sex chromosomal | ||

| 46X,r(X)(p11.2q13) or r(Y)(p11.2q11.2) |

Niikawa et al. [1988] |

|

| 46,X,inv(Y)(p11.2q11.23)pat |

Niikawa et al. [1988] |

|

| 45,X |

Wellesley and Slaney [1994] |

Turner syndrome |

| 45,X/46.X,t(X;Y)(p11;p11) |

Moncla et al. [1996] |

|

| 45,X/46,X,r(X) |

Abd et al. [1997] |

Turner syndrome |

| 45,X/46,X,r(X)(p11.2q13) |

McGinniss et al. [1997] |

|

| Parental | ||

| 46,X/46,XX |

Van Hagen et al. [1996] |

In the mother |

The fact that the majority of patients are sporadic cases and show a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations raises the question whether KMS is a condition with a microdeletion involving several contiguous genes.

The fact that the majority of patients are sporadic cases and show a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations raises the question whether KMS is a condition with a microdeletion involving several contiguous genes.

To answer this question, three trials were performed with the hypothesis that such a deletion would either be located at the DiGeorge/velocardiofacial chromosomal region within 22q11.2, or would flank the van der Woude syndrome (VWS) region at 1q32-q41, because KMS manifestations may overlap the phenotype of the 22q11 deletion syndrome (or CATCH22 phenotype) [Li et al., 1996; Chrzanowska et al., 1998], and a few KMS patients have lower lip pits and many have cleft palate [Makita et al., 1999]. The three groups studied KMS patients by fluorescence in situ hybridization using clones as probes that cover the candidate regions, but they failed to find any chromosomal deletions at the sites. However, because KMS may be heterogeneous to some degrees, the hypothesis has not absolutely been ruled out. As a putative modifier (OMIM *604547) locus for VWS has been assigned to 17p11.2-p11.2, deletion analysis at the site will be necessary.

CONCLUSION

Although a large number of patients have been reported and studied, there have been no direct evidence or any clues to clarify the cause of the syndrome. Besides genetic heterogeneity, submicroscopic deletions with various sizes may exist as an underlying mechanism. Isolation of a gene(s) responsible for KMS will broaden our horizons in understanding human growth and mental development. Microarray analysis with genome-wide comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) is suitable to detect such a deletion.

A STORY BEHIND THE SYNDROME

The first patient, a Japanese newborn girl, was seen in a small municipal hospital by Niikawa in 1969. The girl had a peculiar facies not resembling either of her parents. She was not able to be diagnosed correctly at that time. During Niikawa's four-year study abroad, another pediatrician, Dr. Nobuo Matsuura (currently, Professor of Pediatrics at Kitazato University), was following up the patient in the endocrinology clinic in Hokkaido University Hospital. Dr. Matsuura called the facial characteristic of the patient “Kabuki actor's face”. When Niikawa opened an outpatient clinic of medical genetics, he saw two other patients with a similar appearance in a short period. Niikawa still doubted that he was seeing a certain known disorder, but when summarizing clinical findings, including results of an X-ray survey, he was confident of seeing a hitherto undescribed condition. He presented with his cases as a new MCA/MR syndrome at the first Japan Dysmorphology Conference in 1979. Dr. Yoshikazu Kuroki at Kanagawa Children's Hospital suddenly remembered that he had also seen several patients with the same combination of anomalies. Dr. Kuroki presented with two his cases at the next year's conference, and every conference member became aware of the condition as a new syndrome. After thoroughly reviewing disorders/syndromes reported previously in journals in the field of medical-human genetics and pediatrics, as well as through several computer-based databases, Niikawa et al. [1981] and Kuroki et al. [1981], with a help of a coordinator, Dr. Tadashi Kajii, Professor Emeritus of Yamaguchi University and Chairperson of the Japan Dysmorphology Conference, submitted their reports independently to Journal of Pediatrics as a newly recognized MAC/MR syndrome. The Editor-in-Chief of the journal complained that the term “Kabuki” was not familiar to western clinicians. By the great effort of Professor Kajii, the editor finally accepted the term, and both papers were published. The work by the two Japanese groups was cited in a Yearbook of Pediatrics [Oski and Stockman, 1983] with a wisecrack comment: “It is only a matter of time before it will be exported to the United States. We haven't any really good Japanese exports since Kawasaki disease.”

The name of the syndrome, “Kabuki make-up”, was given by Niikawa et al. [1981] because the facial appearance of patients, especially the eversion of their lower eyelids, is reminiscent of the make-up of actors in Kabuki, the traditional form of Japanese theater. Kabuki was founded early in the 17th century in Japan, and over the next 300 years developed into a sophisticated, highly stylized form of theater (Kabuki home page, “Kabuki for Everyone”, http://www.fix.co.jp/kabuki/kabuki.html). Kabuki actors usually apply traditional make-up to strengthen their eyes, especially in a “hero” play, and are very proud of their performing art. Recently, clinical geneticists in western countries have tended to use the term “Kabuki syndrome”, because they believe the term “make-up” can be offensive to patients and may not be acceptable to some families [Hughes and Davies, 1994; Burke and Jones, 1995; Mhanni and Chudley, 1999]. Conversely however, the “Kabuki syndrome” may be offensive to the Kabuki Society in Japan, and the actors may argue against the name.

Recently, clinical geneticists in western countries have tended to use the term “Kabuki syndrome”, because they believe the term “make-up” can be offensive to patients and may not be acceptable to some families. Conversely however, the “Kabuki syndrome” may be offensive to the Kabuki Society in Japan, and the actors may argue against the name.

One solution may be the use of “Niikawa-Kuroki syndrome”, although the name lacks the visual represention characteristic of the syndrome. For an activity in society, the Kabuki Syndrome Network (http://www.kabukisyndrome.com/index.html) and the Kabuki Syndrome Association have been established in North America and Europe. These groups support patients and their families, and publish The Kabuki Journal periodically (Fig. 4).

The Kabuki Journal.