The Behavioral Phenotype and Importance of Multidisciplinary Care in Patients With Sotos Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience

Funding: This work was supported by the Lorenzo “Turtle” Sartini Jr. Endowed Chair in Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Research (JMK).

ABSTRACT

Sotos syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition caused by pathogenic variants in the NSD1 gene on chromosome 5q35. It is characterized by macrosomia, distinctive facial features, and developmental delays. Patients are also reported to have a behavioral phenotype including autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and increased rates of tantrums and aggressive behavior. Here, we introduce and phenotype a novel cohort of 25 patients with molecularly confirmed Sotos syndrome. We also present the detailed behavioral histories of two patients and provide guidance for managing the behavioral manifestations of Sotos syndrome, highlighting the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to care for patients with this complex overgrowth condition.

1 Introduction

Sotos syndrome is a rare congenital overgrowth condition first described in 1964 by Juan Sotos (Tatton-Brown and Rahman 2007). The condition is caused by pathogenic variants in the nuclear receptor-binding set domain protein 1 (NSD1) gene on chromosome 5q35 and has a prevalence of 1 in 14,000 live births (Baujat and Cormier-Daire 2007; Tatton-Brown and Rahman 2004). Sotos syndrome is characterized by a variety of clinical features, most notably overgrowth, mild intellectual disability, and a distinctive facial appearance (broad, prominent forehead, sparse frontotemporal hair, down-slanting palpebral fissures, malar flushing, bitemporal narrowing, and a long chin) (Tatton-Brown and Rahman 2007). A broad spectrum of childhood cancers has been reported in patients with Sotos syndrome, the most frequently of which include sacrococcygeal teratomas, acute lymphocytic leukemia, and neuroblastomas (Al-Mulla et al. 2004; Grand et al. 2019; Hersh et al. 1992; Jin et al. 2002; Kaya et al. 2022; Kulkarni et al. 2013; Leonard et al. 2000; Lourdes et al. 2023; Nagai et al. 2003; Tatton-Brown et al. 2005; Yule 1999). Routine cancer screenings, however, are typically not recommended as none of these cancer types appear to have a frequency above 1% (Kalish et al. 2024). Patients with Sotos syndrome also often present with advanced bone age, cardiac anomalies, cranial MRI/CT anomalies, renal anomalies, scoliosis, seizures, joint hyperlaxity, and neonatal complications such as jaundice and hypotonia (Tatton-Brown et al. 2005; Tatton-Brown and Rahman 2007).

In addition to these physical features, there has been a broad cognitive and behavioral spectrum reported among patients with Sotos syndrome. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are among two of the most common neurodevelopmental conditions associated with Sotos syndrome (Finegan et al. 1994; Lane et al. 2017). In addition, caregivers have reported increased incidence of tantrums and outbursts as common behavioral manifestations of the condition (Compton et al. 2004; Mauceri et al. 2000). Symptoms of anxiety have also been sporadically reported in this patient population (Rutter and Cole 1991; Sarimski 2003; Siracusano et al. 2023). Outside of these behavioral phenotypes, intellectual disability and developmental delay have previously been reported (Lane et al. 2019; Nagai et al. 2003; Tatton-Brown et al. 2005). A recent study by Siracusano et al. (2023) showed a genotype–phenotype correlation between patients with microdeletions in 5q35 and greater impairment in cognitive functioning compared to patients with intragenic mutations. Nevertheless, the neuropsychological and behavioral profile of Sotos syndrome still remains poorly defined.

Our study presents a single-center cohort of 25 patients with molecularly confirmed Sotos syndrome, 18 of which have not been previously reported in the literature. The behavioral phenotypes found in this novel cohort and the detailed stories of two of the older patients within the cohort were investigated to delineate the complex behavioral spectrum found in patients with Sotos syndrome. With these data and our experience from our multidisciplinary overgrowth clinic, we provide guidance for managing the behavioral manifestations of Sotos syndrome and highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to care for patients with this complex overgrowth condition.

2 Materials and Methods

We collected data from 25 patients with molecularly confirmed Sotos syndrome, all of whom were either evaluated or had records reviewed at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Charts were reviewed and data abstraction was performed under IRB13-010658 and IRB19-016459. Patients under the age of 3 years were excluded from frequency calculations for the following categories: attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, anxiety disorder, and medication for neuropsychological condition. This decision was based on our experience that patients with underlying neuropsychological conditions are typically only diagnosed in our clinic after the age of 3. Informed consent, where applicable, was obtained from all participants or families in this study according to the relevant IRB protocol.

3 Results

There were 25 pathogenic variants of NSD1 identified in this cohort of 25 patients, of which 12 were male and 13 were female. The genotypes and phenotypes of each of the patients in the cohort are reported in Table 1. A characteristic facial appearance (100%), developmental delay (92%), and macrosomia (88%) were the most common features in the cohort. All patients in the cohort presented with a broad and prominent forehead, and 87.5% had a dolichocephalic head shape. In addition, 91.3% had sparse frontotemporal hair and 86.4% had down-slanting palpebral fissures (Table 2). Each of the patients in the cohort had at least two of the features that made up the characteristic facial appearance of Sotos syndrome. Figure 1 highlights some of the facial characteristics of patients in our cohort.

| Feature | CHOP1 | CHOP2 | CHOP3 | CHOP4 | CHOP5 | CHOP6 | CHOP7 | CHOP8 | CHOP9 | CHOP10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| Age at review | 7y | 4y | 5y | 9y | 22mos | 7y | 6y | 7y | 31mos | 3y |

| Genotype | c.5332C>T p.R1778* |

c.6050G>A p.R2017Q |

c.3686C>G p.S1229* |

c.6655C>T p.R2219C |

c.5036C>G p.S1679X |

c.3004_3005del p.L1002fs |

c.4378+3_4738 +6delGAGT |

c.4417C>T p.R1473* |

c.5150G>A p.G1717D |

c.1999G>C p.D557H |

| Facial characteristics | ||||||||||

| Broad and prominent forehead | + | + | + | + | NR | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dolichocephalic head shape | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NR | NR | — |

| Sparse frontotemporal hair | + | + | + | + | — | + | + | + | + | + |

| Downslanting palpebral fissures | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | — | + |

| Malar flushing | — | NR | + | + | NR | + | + | + | NR | — |

| Long and narrow face | + | + | + | — | NR | — | + | NR | — | + |

| Other features | ||||||||||

| Learning disability/developmental delay | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | — |

| Overgrowth | + | — | — | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Behavioral findings | + | + | + | + | NR | + | + | + | NR | — |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | + | + | + | — | NR | + | + | — | NR | — |

| Autism spectrum disorder | + | — | — | — | NR | — | — | + | NR | — |

| Anxiety disorder | + | — | + | + | NR | — | + | — | NR | — |

| Advanced bone age | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | NR | NR |

| Cardiac anomalies | + | + | — | + | + | + | + | — | — | + |

| Cranial MRI/CT abnormalities | + | + | + | NR | + | + | + | + | + | NR |

| Joint hyperlaxity | — | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | + | — |

| Maternal preeclampsia | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | NR |

| Neonatal complications | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Renal anomalies | + | — | — | — | + | — | + | + | + | — |

| Seizures | + | + | — | — | — | — | — | + | — | — |

| Scoliosis | + | + | + | + | — | — | — | + | — | — |

| Hyperinsulinism | + | + | — | — | + | + | — | — | — | + |

| Tumors | + | — | — | — | + | — | — | — | — | — |

| Interventions | ||||||||||

| Developmental pediatrics visit | + | + | + | + | NR | — | + | + | NR | — |

| Speech therapy | + | + | + | — | + | + | + | + | + | — |

| Physical therapy | + | + | + | — | + | + | + | + | + | — |

| Occupational therapy | + | + | + | — | + | + | + | + | + | — |

| Individualized education plan | + | + | + | — | NR | + | + | + | NR | — |

| Medication for neuropsychological condition | + | NR | — | — | NR | + | + | — | NR | — |

| Feature | CHOP11 | CHOP12 | CHOP13 | CHOP14 | CHOP15 | CHOP16 | CHOP17 | CHOP18 | CHOP19 | CHOP20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Age at review | 24mos | 31mos | 8y | 31mos | 27mos | 20mos | 12mos | 32mos | 15mos | 17mos |

| Genotype | arr[GRCh37]5q35.2q35.3 (175,581,649_177,441,189)x1 |

c.2808C>A p.T936* |

c.5308T>G p.W1770G |

arr[GRCh37]5q35.2q35.3(176562237x2,176562264_176714141x1,176714671x2) | c.4242del p.E1414Dfs*5 |

c.5741G>T p.R1914L |

arr[GRCh38]5q35.2q35.3(176131695_178002855)x1 |

c.5918G>A p.G1973D |

c.5780C>A p.A1927D |

c.4416del p.K1472Nfs*15 |

| Facial Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Broad and prominent forehead | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dolichocephalic head shape | + | NR | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | + | + | + |

| Sparse frontotemporal hair | + | + | + | + | NR | + | + | NR | + | + |

| Downslanting palpebral fissures | + | + | + | + | NR | + | — | + | + | + |

| Malar flushing | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | + | NR | + | + | NR |

| Long and narrow face | — | — | + | — | NR | — | NR | + | — | + |

| Other Features | ||||||||||

| Learning disability/developmental delay | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | — |

| Overgrowth | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Behavioral findings | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | NR | NR | — | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Autism spectrum disorder | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Anxiety disorder | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Advanced bone age | NR | + | + | + | + | — | — | + | NR | NR |

| Cardiac anomalies | + | + | — | + | — | — | + | + | + | + |

| Cranial MRI/CT abnormalities | + | + | NR | — | + | + | + | + | — | NR |

| Joint hyperlaxity | + | — | + | + | — | — | — | — | — | NR |

| Maternal preeclampsia | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | — | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Neonatal complications | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Renal anomalies | + | + | — | + | + | + | — | — | — | — |

| Seizures | + | + | + | + | + | — | — | + | + | — |

| Scoliosis | — | — | + | — | + | + | + | — | + | — |

| Hyperinsulinism | — | + | — | + | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tumors | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Interventions | ||||||||||

| Developmental pediatrics visit | + | + | + | NR | + | + | + | + | — | + |

| Speech therapy | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Physical therapy | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Occupational therapy | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Individualized education plan | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Medication for neuropsychological concern | NR | — | — | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Feature | CHOP21 | CHOP22 | CHOP23 | CHOP24 | CHOP25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| Age at review | 21mos | 9y | 8y | 7y | 17y |

| Genotype |

c.3780del p.E1261Sfs*48 |

c.4937T>G p.L1658W |

c.5748_5750dup p.L1917dup |

c.6059A>G p.N2020S |

c.C3964T p.R1322X |

| Facial Characteristics | |||||

| Broad and prominent forehead | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dolichocephalic head shape | NR | — | + | + | NR |

| Sparse frontotemporal hair | + | + | + | — | + |

| Downslanting palpebral fissures | + | NR | + | — | NR |

| Malar flushing | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Long and narrow face | + | NR | + | + | + |

| Other Features | |||||

| Learning disability/developmental delay | + | + | + | + | + |

| Overgrowth | + | + | + | — | + |

| Behavioral findings | NR | + | — | + | + |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | NR | + | — | — | + |

| Autism spectrum disorder | NR | + | — | — | — |

| Anxiety disorder | NR | + | — | + | + |

| Advanced bone age | NR | + | + | NR | NR |

| Cardiac anomalies | — | — | — | + | + |

| Cranial MRI/CT abnormalities | + | + | NR | NR | + |

| Joint hyperlaxity | — | NR | — | — | + |

| Maternal Preeclampsia | — | NR | — | — | NR |

| Neonatal Complications | + | NR | — | + | + |

| Renal Anomalies | — | — | — | — | — |

| Seizures | — | + | — | + | — |

| Scoliosis | + | + | — | — | + |

| Hyperinsulinism | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tumors | — | — | — | — | — |

| Interventions | |||||

| Developmental Pediatrics Visit | — | — | — | — | + |

| Speech Therapy | + | + | + | + | + |

| Occupational Therapy | + | + | + | + | + |

| Physical Therapy | + | + | + | + | + |

| Individualized Education Plan | NR | — | + | + | + |

| Medication for Neuropsychological Condition | NR | + | — | — | + |

- Note: (+), feature present; (-), feature absent; NR, not reported.

| Novel cohort (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 48 (12/25) |

| Facial characteristics | |

| Broad and prominent forehead | 100 (24/24) |

| Dolichocephalic head shape | 87.5 (14/16) |

| Sparse frontotemporal hair | 91.3 (21/23) |

| Down-slanting palpebral fissures | 86.4 (19/22) |

| Malar flushing | 81.8 (9/11) |

| Long and narrow face | 60.0 (12/20) |

| Other features | |

| Learning disability/developmental delay | 92.0 (23/25) |

| Macrosomia and/or macrocephaly | 88.0 (22/25) |

| Behavioral findings | 84.6 (11/13) |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 53.8 (7/13) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 30.8 (4/13) |

| Anxiety disorder | 61.5 (8/13) |

| Advanced bone age | 80.0 (8/10) |

| Cardiac anomalies | 64.0 (16/25) |

| Cranial MRI/CT abnormalities | 89.5 (17/19) |

| Joint hyperlaxity | 34.8 (8/23) |

| Maternal preeclampsia | 42.9 (3/7) |

| Neonatal complications | 95.8 (23/24) |

| Renal anomalies | 40.0 (10/25) |

| Seizures | 48.0 (12/25) |

| Scoliosis | 52.0 (13/25) |

| Tumors | 8.0 (2/25) |

| Hyperinsulinism | 28.0 (7/25) |

| Interventions | |

| Developmental pediatrics visit | 68.2 (15/22) |

| Speech therapy | 92.0 (23/25) |

| Physical therapy | 92.0 (23/25) |

| Occupational therapy | 92.0 (23/25) |

| Individualized education plan | 80.0 (12/15) |

| Medication for neuropsychological condition | 38.5 (5/13) |

Additional high-prevalence features included advanced bone age (80%), cranial MRI/CT anomalies (89%), and neonatal complications such as hypotonia and jaundice (95%).

There were two cases of tumors found among the patients in our cohort, both of which were benign sacrococcygeal teratomas. CHOP1 was diagnosed with a sacrococcygeal teratoma at 2 weeks of age, which was subsequently removed by surgery at 3 weeks of age. CHOP5 was diagnosed with a fetal cystic sacrococcygeal teratoma prenatally and had a debulking procedure performed shortly after birth.

In the cohort, 84.6% of patients were diagnosed with either ADHD, ASD, or an anxiety disorder. Seven patients in the cohort had a diagnosis of ADHD and five had a diagnosis of ASD. In addition, seven patients were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.

In our cohort, 68.2% of patients were seen by our Developmental Pediatrics team. As part of their treatment plans, all but two of the patients in our cohort received speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy for underlying developmental, motor, and speech delays. In addition, 80% of school-age patients in our cohort received an IEP and 38.5% of patients took medication for a neurodevelopmental condition.

3.1 Case Presentation #1

CHOP1 is a 9-year-old female who first presented at the age of 2 weeks with seizures and benign sacrococcygeal teratoma, which was surgically removed. Her clinical history also includes a characteristic facial appearance, macrosomia, developmental delay, hyperinsulinism, and scoliosis. She was first seen by Genetics at the age of 5 months and by our Developmental Pediatrician (DBP) at the age of 18 months. Exome sequencing revealed a pathogenic c.5332C > T, p.R1778* variant in the NSD1 gene of chromosome 5q35 at the age of 8 months, leading to the diagnosis of Sotos syndrome. At her first Developmental Pediatrics visit, she exhibited delays in expressive and receptive communication skills as measured by her performance on the third edition of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development for receptive and expressive communication (Balasundaram and Avulakunta 2024). She was noted to have limited babbling, vocalizations, and overall expressive vocabulary. Due to these delays and her hypotonia, weekly occupational, speech, and physical therapy were recommended. At a follow-up visit when the patient's age was 3 years and 3 months, the family expressed concerns over difficulty obtaining services in their local community.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit at the age of 7 years and 10 months, primarily due to hyperactivity and behavior outbursts in school. The patient's mother reported that the patient had been experiencing an increase in emotional dysregulation and had begun using profanity both at school and at home, often lashing out at her mother. While the patient was reported to have overcome the speech delays that she had experienced at the age of 3 years, she still had difficulty expressing her emotions, which the patient's mother thought was a potential cause of her outbursts. These behaviors were most often seen when the patient was tired and when her daily routine was disrupted. At this follow-up visit, the patient's mother also raised concerns about the patient's tendency to fidget, which was noted by teachers as well. The patient's mother reported “trying everything” in response to the patient's behavior, including time outs, without any success. This led the patient's mother to feel overwhelmed and ask for support in our multidisciplinary clinic.

Given these findings, our clinic's DBP administered the National Institute for Children's Health Quality Vanderbilt Assessment Scale as well as the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) parent scale to the patient's parent and teachers to assess for signs of ADHD and anxiety in the patient (Anderson et al. 2022; Birmaher et al. 1997). The patient was noted to score high in the domain of social anxiety on the SCARED scale. On the Vanderbilt scale, the patient received inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive scores of seven of nine from her mother and an inattentive score of seven of nine and hyperactive/impulsive score of five of nine from her teachers. Given these scores and supporting clinical findings, our clinic's DBP diagnosed the patient with ADHD at the age of 7 years and 11 months. Our DBP recommended parent–child interaction therapy and guanfacine to manage the patient's ADHD. Given her history of mild mitral valve regurgitation and mild aortic valve dilatation, the patient was referred to see cardiology for clearance prior to starting medication for ADHD management. The medication was noted to help with the patient's inattentiveness in school and decrease the number of aggressive outbursts toward the patient's mother.

At a follow-up visit at the age of 8 years and 2 months, the patient reported ongoing difficulties with emotional regulation. At this time, our DBP recommended evaluation via the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and a daily dose of sertraline. With the results of the ADOS assessment and supporting clinical findings, our DBP diagnosed the patient with ASD at the age of 8 years and 4 months and recommended ABA therapy.

Due to continued difficulties with attention, our DBP recommended the patient start taking methylphenidate (MPH), a stimulant medication, at the age of 9 years and 2 months. The patient continues to be followed by our multidisciplinary clinic and has been experiencing fewer outbursts both in school and at home.

3.2 Case Presentation #2

CHOP25 is a 17-year-old male whose clinical history is significant for a characteristic facial appearance, macrosomia, developmental delay, joint hyperlaxity, scoliosis, Crohn's disease, polyhydramnios, mild hypoglycemia, and recurrent ear infections, which were treated with bilateral myringotomy tubes at the age of 1. He was first evaluated by Genetics at the age of 3 days due to his macrocephaly and dysmorphic facial features. At 7 months old, the patient underwent genetic testing and was found to have a pathogenic c.C3964T, p.R1322X variant in NSD1, leading to a diagnosis of Sotos syndrome.

The patient was first seen by Developmental Pediatrics at the age of 10 months, at which point our DBP recommended he started receiving regular speech, physical, and occupational therapy due to motor and speech delays. At the age of 5 years, the patient started formal schooling with kindergarten and was found to have trouble focusing and difficulty getting started in completing tasks. He began receiving extra learning support at school for reading, math, and language arts as well as a personal care assistant for attention and task completion. The patient had less trouble focusing on activities he enjoyed, like building Legos, playing outside, and horseback riding.

The patient was found to be occasionally aggressive toward his peers in class, sometimes invading their personal space. He was reported to have a great memory but would not always respond to either positive reinforcement or negative consequences. At the age of 5 years and 11 months, the patient was evaluated by our DBP and diagnosed with ADHD and a specific learning disorder in writing. The family's biggest concern was the patient's ability to focus in school. He was noted to need constant prompting by his school aide to stay on task and complete work. At the age of 7 years, our DBP recommended that the patient begin taking MPH daily, which was noted to improve his inattentiveness and aggressive behaviors but led to decreased appetite.

At the age of 7 years and 4 months, our team switched the patient's MPH regimen from Metadate to Concerta, primarily due to an increase in aggressive behaviors, cursing, and tantrums in the afternoons, thought to be a rebound effect of his Metadate regimen. While taking MPH in the form of Concerta, the patient was reported to be more focused and attentive than his baseline behavior. However, the patient still needed constant prompting and reminders to complete tasks and often struggled with motivation. He also began a habit of picking at his skin, fingers, and forehead.

At the age of 8 years and 6 months, our DBP recommended the patient begin taking dexmethylphenidate instead of MPH due to his flat affect while on MPH. Both teachers and parents reported the patient to be more animated and natural on dexmethylphenidate. The patient also had considerably less skin picking compared to when he was taking MPH, though he still often complained of being tired in the afternoon. The patient also continued to have decreased appetite while on dexmethylphenidate. Given the patient's continued difficulties with attention and outbursts, our DBP recommended wraparound therapy.

At the age of 9 years, the patient began receiving wraparound therapy, including 3 hours per week of support from a behavioral specialist consultant and 2 hours per week of support from a mobile therapist, which helped reduce the frequency of his outbursts and aggressive behavior. Our DBP team continued to follow the patient and monitor his ADHD. On the Vanderbilt Assessment Scale, the patient received the maximum score of nine for inattentive behavior and a four of nine for hyperactive behavior (Anderson et al. 2022). The biggest concerns for the patient remained his difficulty focusing in school even with a 1:1 aide and his wraparound therapy. He continued to require constant prompting and often lost motivation on tasks. Our DBP recommended a review of the patient's individualized education program (IEP) to provide additional resources for the patient. Around this time, the patient also began exhibiting enuresis and encopresis, which led parents to start a reward chart to incentivize the patient against having accidents. He also started showing signs of anxiety, particularly with an aversion to dogs. With the help of his mobile therapist, the patient was eventually able to overcome this fear.

The patient continued to improve in school with the help of medication, wraparound therapy, his 1:1 aide, and learning support teachers. He experienced issues with bullying in school, with his peers excluding him from games, but the issue was eventually resolved after intervention by the patient's teacher. After the incident, the patient was reported to be doing well with his peers.

The patient continued to be seen biannually by our Developmental Pediatrics team for management of his ADHD and anxiety until the age of 17. Throughout that time, the patient received regular support from his school, including a 1:1 aide, an IEP, and wraparound therapy. His ADHD is currently managed by daily MPH, and he is doing significantly better in school. He started a job at a retirement community 2 years ago and began transitioning to learning in school without an aide. Most recently, the patient made his school's honor roll, and he is currently in his final year studying carpentry.

4 Discussion

This study presents a large novel cohort of patients with Sotos syndrome, allowing for the further characterization of the incidence of common Sotos features—in particular the characteristic facial appearance, overgrowth, and developmental delay. Particular attention was given to the behavioral presentations of these patients, with a more extensive behavioral history provided for two of the older patients within the cohort.

5 Characteristic Facial Appearance

The characteristic facial appearance of Sotos syndrome, which includes a prominent forehead, dolichocephalic head shape, and anterior hairline, has long been used as a diagnostic tool for the condition (Castro et al. 2021; Dodge et al. 1983; Tatton-Brown et al. 1993). All 25 patients in our cohort presented with a dysmorphic facial appearance that is characteristic of Sotos syndrome. In all these cases, the characteristic appearance was noted before molecular testing was performed. The prevalence of characteristic facial features in our cohort highlights the importance of dysmorphic appearance in the diagnostic process. The facial gestalt associated with Sotos syndrome does tend to evolve over time as patients age (Figure 1). Most notably, the forehead is found to become less prominent, the pointed chin squarer, and jaw line less pronounced (Castro et al. 2021; Foster et al. 2019). This makes the facial findings of Sotos syndrome more difficult to identify with age, an important consideration when evaluating older patients for an overgrowth condition.

6 Tumors

There were two cases of benign sacrococcygeal teratomas found in our cohort, seen in CHOP1 and CHOP5. In both cases, the benign tumors were removed via surgery and no further complications were found. Sacrococcygeal teratomas have previously been reported in patients with Sotos syndrome along with other forms of cancer like acute lymphocytic leukemia and neuroblastomas (Al-Mulla et al. 2004; Grand et al. 2019; Hersh et al. 1992; Jin et al. 2002; Kaya et al. 2022; Kulkarni et al. 2013; Leonard et al. 2000; Lourdes et al. 2023; Nagai et al. 2003; Tatton-Brown et al. 2005; Yule 1999). However, none of these cancers appear to cross the 1% screening threshold recommended by the American Association for Cancer Research, and routine cancer screening is not currently recommended for patients with Sotos syndrome (Kalish et al. 2024). The presence of tumors like sacrococcygeal teratomas in this patient population nevertheless highlights the complexity of clinical presentations found in patients with Sotos syndrome and underscores the importance of multidisciplinary care for this patient population.

7 Behavioral Phenotypes

ADHD and ASD have been reported as two of the most common neurodevelopmental conditions associated with Sotos syndrome (Lane et al. 2017). There have been multiple case reports of individuals with comorbid Sotos syndrome and ASD (Morrow et al. 1990; Mouridsen and Hansen 2002; Trad et al. 1991). In addition, previous cohorts by Lane et al. (2016), Sheth et al. (2015), and Timonen-Soivio et al. (2016) have shown an increased incidence of ASD in individuals with Sotos syndrome. Sheth et al. (2015) reported characteristics of 38 patients with Sotos syndrome and found that 26 (68.42%) of the 38 patients met the clinical cut-off for ASD as assessed by the social communications questionnaire. Lane et al. (2016) found that 65 (83%) of the 78 patients in their cohort with Sotos syndrome met clinical cut-off for ASD according to the Social Responsiveness Autism Scale. In our cohort, 5 (38.5%) of 13 patients over the age of 3 were diagnosed with ASD, which supports the increased incidence of ASD in patients with Sotos syndrome. Many of the younger patients in our cohort were noted to display early signs of ASD as well, which may explain the lower incidence of ASD in our cohort compared to those previously reported in the literature.

In addition to ASD, ADHD has been previously linked to Sotos syndrome. Finegan et al. (1994) reported 27 patients with Sotos syndrome and found that 10 (37.0%) individuals met clinical characteristics of ADHD according to the Child Behavior Checklist. Varley and Crnic (1984) found that 3 (27.3%) of the 11 patients in their cohort met the clinical threshold of ADHD. In our cohort, 7 (53.8%) of 13 patients over the age of 3 had a diagnosis of ADHD, which adds to the evidence of a link between ADHD and Sotos syndrome.

Outside of ASD and ADHD, there appeared to be an increased rate of reported anxiety in our cohort. Thus far, there have been few reports of increased rates of anxiety in patients with Sotos syndrome. Sarimski (2003) conducted a study that showed significantly more separation anxiety in patients with Sotos syndrome compared to age and cognitive-matched controls according to the Children's Social Behavior Questionnaire. The study also found that the Sotos group had higher scores in insecure/anxious behavior as measured by the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (Sarimski 2003). In our cohort, 7 (53.8%) of 13 patients over the age of 3 had reported increased anxiety, which supports Sarimski's findings. CHOP25, for example, developed a fear of dogs at the age of 8, which required extensive counseling and therapy to overcome. The prevalence of anxiety in patients with Sotos syndrome remains an area of future study.

In addition to neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric conditions, patients with Sotos syndrome have been reported to exhibit more tantrums and display more aggressive behavior (Compton et al. 2004; Mauceri et al. 2000). Both CHOP1 and CHOP25 were noted to have increased incidences of aggressive behaviors and temper tantrums by their caregivers and teachers. The presence of these aggressive behaviors in patients with Sotos syndrome remains an area of future study.

8 Multidisciplinary Care for Sotos Syndrome

The prevalence of ADHD, ASD, anxiety, and aggressive behaviors in patients with Sotos syndrome highlights the need for longitudinal multidisciplinary care for these patients.

As seen in our cohort, 68% of patients were seen by our DBP team during the course of their care. Nearly all our patients received speech therapy, occupational therapy, and/or physical therapy for underlying developmental, motor, and/or speech delays. In addition, 80% of patients in our cohort received an IEP in their school, highlighting the importance of careful coordination between providers, caregivers, teachers, and school administration. Outside of these physical interventions, nearly 40% of patients took medication for a neurodevelopmental condition, most often ADHD. Importantly, the combination of interventions needed for patients in our cohort changed over time. For example, ADHD in the cases of CHOP1 and CHOP25 was managed using a combination of stimulant medication and educational supports like IEPs and school aids. In both cases, the medication regimen and educational supports provided to patients evolved as the needs and concerns of the patients changed. Without regular follow-up and coordination between caregivers, providers, and school staff, such efforts to adapt interventions would not have been possible.

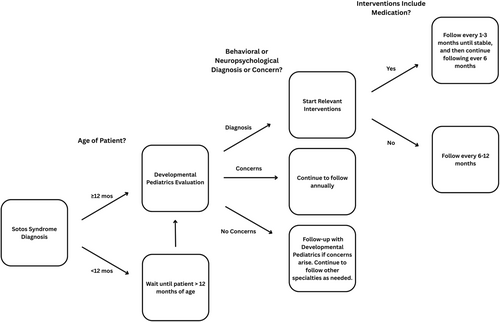

Based on our experience in our multidisciplinary overgrowth clinic and the data collected in this study, we recommend an initial DBP evaluation between the ages of 12 and 24 months for patients with Sotos syndrome. During this visit, we recommend careful attention be paid to signs of the most frequent behavioral and neurodevelopmental concerns for patients with Sotos syndrome, which include developmental delay, motor delay, speech delay, ASD, ADHD, anxiety, and aggressive behavior or tantrums. A list of common evaluation methods and interventions for these conditions are listed in Table 3. Depending on the results of this initial evaluation, we recommend annual, biannual, or quarterly follow-up with DBP and adjustment of interventions as concerns change over time (Figure 2).

| Neuropsychological condition or behavioral concern | Evaluation and/or diagnostic tools | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental delay |

For patients under the age of 3 years: CAT/CLAMS For patients under the age of 5 years: Gesell development assessments for gross motor, fine motor, self-help, problem solving, receptive language, and expressive language For patients over the age of 5 years: Psychoeducational testing and/or IEP evaluation |

For patients under the age of 3 years: Utilize resources under local EI programs Outpatient PT, OT, ST as needed For patients over the age of 3 years: Utilize resources through school (e.g., IEP) or county, depending on resources available in area Outpatient PT, OT, ST as needed |

| Speech delay |

For patients under the age of 3 years: CAT/CLAMS |

For patients under the age of 3 years: ST under EI For patients over the age of 3 years: ST through school, county, or private practice, depending on resources available in area |

| Motor delay |

For patients under the age of 5 years: Gesell Development Assessments for gross motor and fine motor domains |

For patients under the age of 3 years: PT and/or OT through EI For patients over the age of 3 years: PT and/or OT through school, county, or private practice depending on resources available in area |

| ADHD |

For patients over the age of 6 years: a National Institute for Children's Health Quality Vanderbilt Assessment Scale to parents and teachers |

For patients under the age of 6 years: BPT Classroom intervention (e.g., IEP) Consider medication management if above interventions are unsuccessful For patients over the age of 6 years: BPT Classroom intervention (e.g., IEP) Medication management |

| ASD |

For all patients: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (2nd edition) DSM-5 Checklist for Autism Spectrum Disorder Consider Social Responsiveness Scale if diagnostic uncertainty |

For patients under the age of 3 years: Appropriate services through EI ABA therapy For patients over the age of 3 years: School based services (e.g., PT, OT, ST) ABA therapy For school-aged patients: Outpatient social skills group |

| Anxiety |

For patients above the age of 8 years: Screen for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders |

For all patients: Cognitive behavioral therapy with or without medication management |

| Tantrums/aggressive behavior |

For all patients: Review of clinical history and reports from teachers and/or parents |

For all patients: ABA therapy OT for emotional regulation For patients above the age of 3 years: Parent–child interaction therapy For patients above the age of 6 years: Medication management as needed |

- Abbreviations: ABA, applied behavioral analysis; BPT, behavior parent training; CLAMS, clinical adaptive test/clinical linguistic auditory milestone scale; EI, early intervention; OT, occupational therapy; PT, physical therapy; ST, speech therapy.

- a National Institute for Children's Health Quality Vanderbilt Assessment Scale is validated for patients over the age of 6 years. However, the assessment is commonly used for patients under the age of 6 years at the provider's discretion.

9 Conclusion

In this study, we presented and phenotyped a novel cohort of patients with molecularly confirmed Sotos syndrome. The behavioral presentations of two of the older patients in the cohort were highlighted in detail. The prevalence of neurodevelopmental, neuropsychiatric, and behavioral challenges in this patient population underscores the importance of multidisciplinary care and coordination between providers, caregivers, and school administration. Using our cohort and experience with our multidisciplinary overgrowth clinic, we also provide guidance for managing the behavioral manifestations of Sotos syndrome and highlight the need for multidisciplinary care for this patient population. The longitudinal changes in the behavioral characteristics of patients with Sotos syndrome and complete phenotypic spectrum of this rare overgrowth condition remain areas of future study.

Author Contributions

Aravind Viswanathan: investigation; writing original draft and review. Andrew M. George: investigation; writing original draft and review. Evan R. Hathaway, Carlyn Glatts: investigation; writing review. Jennifer M. Kalish: conceptualization; supervision; investigation; writing review and editing.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Victoria Fertitta Fund through the Lorenzo “Turtle” Sartini Jr. Endowed Chair in Beckwith–Wiedemann Syndrome Research (JMK). We thank the patients and their family members for their participation in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.