A novel patient with White–Sutton syndrome refines the mutational and clinical repertoire of the POGZ-related phenotype and suggests further observations

Abstract

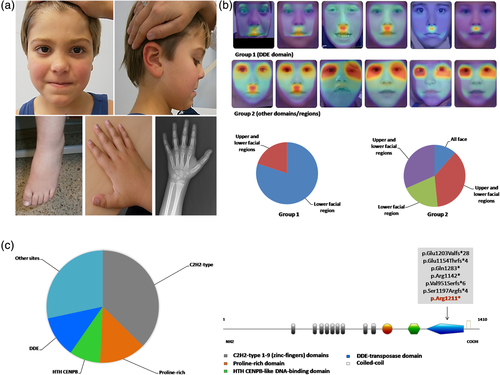

A rare developmental delay (DD)/intellectual disability (ID) syndrome with craniofacial dysmorphisms and autistic features, termed White–Sutton syndrome (WHSUS, MIM#614787), has been recently described, identifying truncating mutations in the chromatin regulator POGZ (KIAA0461, MIM#614787). We describe a further WHSUS patient harboring a novel nonsense de novo POGZ variant, which afflicts a protein domain with transposase activity less frequently impacted by mutational events (DDE domain). This patient displays additional physical and behavioral features, these latter mimicking Smith–Magenis syndrome (SMS, MIM#182290). Considering sleep–wake cycle anomalies and abnormal behavior manifested by this boy, we reinforced the clinical resemblance between WHSUS and SMS, being both chromatinopathies. In addition, using the DeepGestalt technology, we identified a different facial overlap between WHSUS patients with mutations in the DDE domain (Group 1) and individuals harboring variants in other protein domains/regions (Group 2). This report further delineates the clinical and molecular repertoire of the POGZ-related phenotype, adding a novel patient with uncommon clinical and behavioral features and provides the first computer-aided facial study of WHSUS patients.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recently, mutations in POGZ (KIAA0461, MIM#614787) have been associated with White–Sutton syndrome (WHSUS, MIM#616364), a rare neurodevelopmental disorder, part of the group of chromatinopathies, which is mainly characterized by developmental delay (DD)/intellectual disability (ID), dysmorphisms, autistic features, brain anomalies, and overweight (White et al., 2016). Other common manifestations include sleep disorders (apnea and other general anomalies), behavioral disturbances, feeding problems, visual and audiological defects. Main craniofacial anomalies comprise microbrachycephaly, hypertelorism, flat malar ridge, midface hypoplasia, and prognathism. So far, single case reports and more conspicuous studies regarding the POGZ-associated phenotype have been provided (Fukai et al., 2015; Ye et al., 2015; Hashimoto et al., 2016; Stessman et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2016; White et al., 2016; Dentici et al., 2017; Du, Gao, Liu, et al., 2018; Ferretti et al., 2019; Samanta et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Assia Batzir et al., 2020).

Here, we report a further patient with a novel POGZ nonsense variant, afflicting a protein domain less frequently impacted by mutations (DDE, transposase domain). He shows unusual manifestations, consisting of physical and behavioral anomalies, these latter mimicking Smith–Magenis syndrome (SMS, MIM#182290).

In view of facial appearance and abnormal behavior, we emphasized the WHSUS clinical overlap with SMS, corroborating to consider the POGZ-related phenotype as an emergent clinical differential diagnosis. CLINIC application of the DeepGestalt technology (FDNA Inc., Boston, Massachusetts; https://www.face2gene.com), which we interrogated, confirms this clinical resemblance. Moreover, using the same tool, we performed a novel facial experiment detected a low correspondence of patients with mutations in DDE domain with the WHSUS syndrome-composite-Gestalt in comparison to individuals harboring variants in the other protein domains/regions, suggesting a possible genotype–phenotype correlation.

2 CLINICAL REPORT

This study and its publication were approved by the patient's family and the Internal Review Board of the main involved Institution. It was conducted according to the Helsinki declaration.

The child came to our attention at age 5 years presenting with borderline ID (IQ 74), autism (especially restricted interests, refusal to changes), abnormal motor coordination, attention deficit, and dysmorphic facies. He was born at term after regular pregnancy from non-consanguineous parents. Birth parameters resulted length 50 cm (50th centile), occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) 33 cm (10th-fifth centile), weight 2,880 g (fifth-10th centile). Family history was unremarkable. He was fed with breast milk until the age of 21 weeks while cow's milk was introduced in his diet at 15 months. He reached a sitting position when he was 32 weeks and walked alone at 18 months of age.

At our clinical examination, his height was 126 cm (>97th centile), weighted 33 kg (>97th centile) and showed an OFC of 52 cm (25th–50th centile). Appreciated dysmorphisms included brachycephaly, broad forehead, bulbous nose with wide nasal ridge and broad nasal tip, thin upper and thick vermilion lower lip, highly arched eyebrows, long and smooth philtrum, and prognathism (Figure 1a). He also exhibited a widow's peak and mild macroglossia. This patient suffered from anxiety, aggressiveness, sleep disturbance, including sleep–wake cycle abnormalities, and astigmatism. He was aggressive, especially toward his parents, and light intolerant. Language was severely impaired. He pronounced only a few words, such as ma-ma and da-da, and was unable to formulate entire phrases. He appeared sleepy and not very interacting. Dysphagia and drooling were also present. In addition to macroglossia and tall stature, other previously undescribed manifestations include hepatomegaly, increased plasmatic levels of tyrosine, alanine and valine, knees valgismus, diastasis recti, high pain tolerance, and atypical neurobehavioral anomalies. These latter comprised tendencies to pulling out fingernails and toenails (onychotillomania), to insert foreign objects into body orifices (polyembolokoilamania), agoraphobia and sporadic anomalous temporospatial orientation. In addition, he showed broad toes, joint hyperlaxity, cardiovascular anomalies (aortic bicuspid valve with mild ascending aorta dilatation), and absent cocleo-stapedial reflexes. Electroencephalography was normal while a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated hypoplasia of the inferior portion of the cerebellar vermis with a wide communication between the IV ventricle and pericerebellar fluid spaces.

After obtaining the informed consent for genetic analysis, he underwent standard karyotype and array-CGH at ~100 kb resolution with a negative result. Subsequently, family-based whole-exome sequencing was performed, allowing the identification (Twist Bioscience, San Francisco, California) of a novel de novo nonsense variant in the POGZ gene (NM_015100.3, c.3631C>T;p.Arg1211*). Sequencing analysis excluded other significant variants in genes associated with the current phenotype, including the clinically overlapping SMS. The present variant is predicted to result in a truncated protein, disrupting its transposase activity (DDE domain).

3 DISCUSSION

We described a novel WHSUS patient with an unreported POGZ nonsense variant in the DDE domain and additional clinical features. POGZ is a Pogo-transposable element involved in chromatin remodeling nd chromosome segregation (Nozawa et al., 2010), containing a central cluster of nine C2H2-type zinc fingers, one Helix-turn-helix centromere protein B-like DNA-binding domain (HTH CENPB) and one DDE domain, this latter functioning as transposase (Figure 1c). Most of WHSUS to date disclosed mutations have been found to frequently impact the zinc-fingers motifs and other protein sites/domains, while the DDE domain resulted to be less involved (Figure 1c).

Our proband displayed the typical core phenotype of WHSUS, consisting of DD/ID, autistic features and mild dysmorphisms, concomitant with other uncommon physical manifestations, already illustrated. Based on our clinical review of all to date reported patients with mutations in the DDE domain and in the other protein regions, he resulted to be the first with cerebellar vermis hypoplasia and, among individuals with mutations in the same domain, the only with congenital cardiovascular defects, which have been reported in a minority of WHSUS patients (Table 1). Interestingly, sleep anomalies, behavioral disturbances, microcephaly, and gastrointestinal/feeding issues result to be more frequent in DDE domain mutated individuals, while central nervous system (CNS) and genitourinary malformations preferentially occur in patients with a variant in other protein sites (Table 1). The present child manifests an abnormal sleep–wake cycle, whose presence has been already specified in a few other individuals, presenting with frequent wakes-up, difficulties getting to sleep, sometimes responsive to melatonin, and excessive daytime drowsiness (Stessman et al., 2016; White et al., 2016). Sleep–wake cycle disturbance concomitant with onichothyllo-polyembolokoilamania could reinforce the marked clinical overlap between WHSUS and SMS. This is a DD/ID syndrome caused by mutations in the chromatin regulator RAI1 (Retinoic Acid-Induced Gene 1, MIM#607642) and mostly characterized by craniofacial dysmorphic features (brachycephaly with flat midface, prominent forehead, broad nasal bridge, synophrys, downturned upper lip with protruding premaxilla, prognathia, and low-set ears) and abnormal behavior, including head banging, wrist biting, and onychothyllo-polyembolokoilamania. In order to verify the clinical overlap between WHSUS and SMS, we analyzed frontal images of 38 available WHSUS patients through the CLINIC application of Face2Gene platform (FDNA Inc.; https://www.face2gene.com), which identified SMS among the 30 automatically suggested syndromes as a tentative diagnosis in 18/38 (47%) cases, based only on facial gestalt. This can be also supposed considering the previously proved biological interactions between the RAI1 and POGZ molecular pathways (Loviglio et al., 2016).

| Clinical features | Other domains | DDE domain | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fukai | White | Hashimoto | Ye | Stessman | Tan | Dentici | Du | Ferretti | Samanta | Zhao | Assia Batzir | Tot. (%) | Stessman | Assia Batzir | Present patient | Tot. (%) | |||||||

| Patients (n) | n = 1 | n = 5 | n = 1 | n = 6 | n = 29 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 18 | 66 | EE1 | UMCN 3 | UMCN8 | UMCN9 | Pt 6 | Pt 19 | Pt 21 | Pt 22 | n = 1 | 9 |

| ID/DD | 1/1 | 5/5 | 1/1 | 6/6 | 22/29 | 1/1 |

1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 11/18 | 52/66 (78) | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 9/9 (100) |

| ASD | 1/1 | 2/5 | 1/1 | 1/6 | 18/29 | 0/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 8/18 | 35/66 (53) | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | na | na | 1/1 | 5/9 (55) |

| Speech impairment | 1/1 | 1/5 | 1/1 | na | 22/29 | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 18/18 | 48/66 (72) | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 7/9 (77) |

| Behavioral alterations/stereotypies/hyperactivity | 1/1 | 4/5 | na | 1/6 | 14/29 | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | a | 24/66 (36) | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | a | a | a | a | 1/1 | 5/9 (55) |

| Seizures/altered EEG | na | 1/5 | 0/1 | na | 2/29 | na | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 4/18 | 10/66 (15) | na | 0/1 | na | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/9 (22) |

| Sleep disturbance | na | 2/5 (a) 1/5 (s-w) | na | na | 3/29 2/29 (a) 3/29 (s-w) | na | na | na | na | na | 0/1 | a | 11/66 (16) | 1/1 (a) | na | 1/1 | na | a | a | a | a | 1/1 (a, s-w) | 3/9 (33) |

| CNS malformation | 0/1 | 3/5 | 0/1 | 5/6 | 8/29 | na | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | 9/18 | 28/66 (42) | na |

na | na | na | na | 1/1 | 0/1 | na | 1/1 | 2/9 (22) |

| Microcephaly | 0/1 | 3/5 | na | 3/6 | 8/29 | 0/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 0/1 | na | 10/18 | 26/66 (39) | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 (macro) | 6/9 (66) |

| Craniofacial dysmorphisms | 1/1 | 5/5 | na | 6/6 | 11/29 | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | a | 27/66 (40) | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | a | a | a | a | 1/1 | 4/9 (44) |

| Short stature/failure to thrive | 1/1 | 4/5 | na | 1/6 | na | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | na | a | 9/66 (13) | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | na | a | a | a | a | 0/1 (tall) | 2/9 (22) |

| Abnormal extremities | na | 2/5 | na | 5/6 | 3/29 | na | 1/1 | na | na | na | na | a | 11/66 (16) | na | na | na | na | a | a | a | a | 1/1 | 1/9 (11) |

| Cardiovascular defect | na | 1/5 | na | na | 1/29 | na | 1/1 | na | na | na | na | a | 3/66 (4) | na | na | na | na | a | a | a | a | 1/1 | 1/9 (11) |

| Genitourinary anomalies | na | 2/5 | na | na | 3/29 | na | na | na | na | na | na | a | 5/66 (7) | na | na | na | na | a | a | a | a | na | 0/9 |

| Hearing/vision/ocular abnormalities | na | 3/5 (h) 5/5 (v) | na | 1/6 | 10/29 (v) | na | 1/1 (h) | na | 1/1 (h) | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/18 (h) 12/18 (o) | 39/66 (59) | 1/1 (v) | na | 0/1 | 1/1 (v) | 1/1 (h, v) | 1/1 (v, o) | 1/1 (o) | na | 1/1 (v, h) | 6/9 (66) |

| GI procedures/feeding problems | na | 4/5 | na | na | 6/29 | na | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 4/18 | 17/66 (26) | na | 1/1 | 1/1 | na | na | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 4/9 (44) |

| Overweight | 0/1 | 1/5 | na | 1/6 | 13/29 | 0/1 | 0/1 | na | 0/1 | 0/1 | na | 2/18 | 17/66 (26) | 1/1 | na | 1/1 | na | na | na | na | na | 1/1 | 3/9 (33) |

- Note: Only published individuals with available clinical description attributable to the impacted protein domain have been considered. Patients with genomic imbalances have been not included.

- Abbreviations: na, not acquired; DD/ID, developmental delay/intellectual disability; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; EEG, electroencephalography; CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; a, apnea; s–w, sleep–wake cycle; h, hearing; v, vision; o, ocular.

- a Not available for single protein domain.

Interestingly, analyzing with the heat-map comparison one frontal image of the present patient and of 26 published WHSUS examinable individuals in the CLINIC application of the DeepGestalt technology (version 19.1.1), it appears that the facies of patients with mutations afflicting the DDE domain (Group 1) shows a lower correlation with the WHSUS syndrome-composite-Gestalt than subjects with variants in the other domains/regions (Group 2) (see red-yellow halo localized to the philtrum and perioral region in Group 1 and to the periorbital/oral districts in Group 2 in Figure 1b). This could suggest a possible genotype–phenotype correlation.

Concluding, here we report a novel WHSUS patient with additional clinical features, behavioral anomalies, reminiscent SMS, and undescribed POGZ variant afflicting a protein domain not so frequently impacted. Remarkably, it seemed that the main dysmorphisms of individuals with a mutation in the DDE domain are restricted to the lower facial portion, with a minor overlap with the WHSUS syndrome-composite-Gestalt (Figure 1b).

Being WHSUS a rare DD/ID condition, its further understanding also through single patient description could be, in our opinion, of general interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the family of the patient for kind cooperation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Nicole Fleischer in an employee of FDNA Inc., providing Face2Gene.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Giulia Pascolini performed clinical genetics evaluation of the patient, conceived and wrote the manuscript; Emanuele Agolini contributed to write the manuscript and performed molecular analyses; Nicole Fleischer contributed to write the manuscript and gave her support for the DeepGestalt experiment; Elisa Gulotta performed the neuropsychiatric evaluation of the patient; Claudia Cesario and Gemma D'Elia performed molecular analyses; Antonio Novelli supervised molecular analyses; Silvia Majore performed clinical genetics evaluation of the patient and contributed to supervise the manuscript; Paola Grammatico supervised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.