Emotional functioning among children with neurofibromatosis type 1 or Noonan syndrome

Funding information: National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: P30 CA77598, UL1TR002494

Abstract

While neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and Noonan syndrome (NS) are clinically distinct genetic syndromes, they have overlapping features because they are caused by pathogenic variants in genes encoding molecules within the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Increased risk for emotional and behavioral challenges has been reported in both children and adults with these syndromes. The current study examined parent-report and self-report measures of emotional functioning among children with NF1 and NS as compared to their unaffected siblings. Parents and children with NS (n = 39), NF1 (n = 39), and their siblings without a genetic condition (n = 32) completed well-validated clinical symptom rating scales. Results from parent questionnaires indicated greater symptomatology on scales measuring internalizing behaviors and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in both syndrome groups as compared with unaffected children. Frequency and severity of emotional and behavioral symptoms were remarkably similar across the two clinical groups. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were higher in children who were also rated as meeting symptom criteria for ADHD. While self-report ratings by children generally correlated with parent ratings, symptom severity was less pronounced. Among unaffected siblings, parent ratings indicated higher than expected levels of anxiety. Study findings may assist with guiding family-based interventions to address emotional challenges.

1 INTRODUCTION

Increased risk for emotional and behavioral challenges is frequently reported in pediatric chronic diseases such as epilepsy, sickle cell disease, and cystic fibrosis, as well as a variety of genetic conditions (e.g., neurofibromatosis type 1 [NF1], Turner syndrome, and fragile X syndrome) (Chong et al., 2016; Hijmans et al., 2009; Lesniak-Karpiak, Mazzocco, & Ross, 2003; Smith, Modi, Quittner, & Wood, 2010). For children with chronic health conditions, a complex array of factors may contribute to emotional problems such as anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal (Schwartz, Tuchman, Hobbie, & Ginsberg, 2011). Investigating common factors that contribute to emotional distress across disorders, as well as contributing factors that are unique to each specific syndrome, may lead to more effective approaches to preventing, identifying, and treating emotional distress. For instance, identification of a key factor (e.g., chronic pain) contributing to emotional distress across two separate conditions may facilitate application of an intervention designed for one patient group to individuals with the other condition. Conversely, where research identifies an important risk factor that is distinct to a condition (e.g., side effects of a specific medication used to treat the disease), prevention and treatment approaches can be designed to address that specific element of vulnerability.

When investigating emotional functioning in children with genetic syndromes, it can be especially challenging to distinguish the relative influences of the neurodevelopmental differences that arise from the genetic pathology from the influences of the medical and psychosocial sequelae of the disorder (e.g., beliefs/expectations about medical risk, disruption to school and family activities). For this reason, studying disorders that have a shared molecular genetic pathology, but that differ in terms of clinical presentation, is instructive. This approach allows investigators to consider the relative influence of genetic, medical, and environmental factors on emotional and behavioral presentation. The current study focused on two genetic disorders that are caused by alterations in a common molecular signaling pathway, but whose most prominent medical features are fairly distinct.

Gene mutations within the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase (RAS-MAPK) signaling cascade cause a spectrum of genetic syndromes known as “RASopathies.” NF1 and Noonan syndrome (NS) are the two most common RASopathies. These two syndromes can either be inherited from an affected parent, or they can occur for the first time in a child as the result of a de novo mutation. The features of NF1 and NS can vary substantially from one person to the next, and even among family members with the same genotype. Both syndromes are associated with heightened risk for chronic medical conditions, including skin manifestations, cardiac disease, skeletal problems, and growth delays. NF1 is caused by pathogenic variants in the NF1 gene and is characterized predominately by cutaneous features (e.g., café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling), neurofibromas, Lisch nodules, optic pathway gliomas, and skeletal anomalies. NF1 is estimated to occur in 1:3,000 births (Friedman, 1999; Lammert, Friedman, Kluwe, & Mautner, 2005). Pathogenic variants in one of more than 10 different genes can cause NS (Aoki, Niihori, Inoue, & Matsubara, 2016), which has an estimated incidence of 1:1,000 to 1:2,500 births (Mendez & Opitz, 1985). Prominent features of NS include congenital heart disease, craniofacial characteristics, and short stature (Roberts, Allanson, Tartaglia, & Gelb, 2013).

Among the organ systems most commonly impacted in all RASopathies is the central nervous system. Disruption to molecular, cellular, and neural systems as a result of gene mutations in the RAS-MAPK pathway can lead to a multitude of neurobiological differences, including neuroanatomical abnormalities, aberrant white matter microstructure, impaired synaptic plasticity, and altered neurotransmitter function (Johnson et al., 2018; Loitfelder et al., 2015; Mainberger, Langer, Mall, & Jung, 2016; Shilyansky et al., 2010). While most individuals with NF1 or NS have intact intellectual function, there is increased vulnerability to a variety of well-documented neurodevelopmental disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and learning disabilities (Eijk et al., 2018; Lehtonen, Howie, Trump, & Huson, 2013; Pierpont, 2016). These types of learning and behavioral challenges can adversely impact various important life outcomes, including academic performance, employment opportunities, financial and functional independence, interpersonal relationships, and quality of life (Cohen, Levy, Sloan, Dariotis, & Biesecker, 2015; Smpokou, Tworog-Dube, Kucherlapati, & Roberts, 2012).

With respect to emotional functioning, a number of studies have found that internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and loneliness) occur with greater frequency and severity than externalizing symptoms (e.g., aggression, rule-breaking behaviors) in both children with NF1 (Allen, Willard, Anderson, Hardy, & Bonner, 2016; Coutinho et al., 2017; Graf, Landolt, Mori, & Boltshauser, 2006) and children with NS (Alfieri et al., 2014). In studies involving individuals with NF1, internalizing symptoms have been found to correlate with overall disease severity in some studies (Martin et al., 2012), but not in others (Rietman et al., 2018). The number of stressful life events and the extent of pain interference in the person's life have been associated with internalizing symptoms in NF1, although the direction of this relationship is not always clear (Martin et al., 2012; Wolters et al., 2015). In terms of psychological predictors, there is emerging evidence that symptoms of ADHD are associated with more internalizing symptoms in children with RASopathies. Mautner, Kluwe, Thakker, and Leark (2002) found significantly higher parent-rated symptoms of anxiety and depression among children with comorbid presentations of NF1 and ADHD than among children with NF1 only.

The current study utilized broadband scales to evaluate the emotional and behavioral functioning of children with NF1 in comparison to children with NS. A primary goal of the study was to assess whether emotional symptoms were similar in frequency and severity across these two clinical groups, and whether these symptoms were higher as compared to children living in a similar psychosocial environment who did not have a genetic pathology (i.e., unaffected siblings). Based on previous work, we hypothesized that both groups would have higher rates of internalizing symptoms than their siblings without a neurogenetic disorder. Secondary goals of the study were to assess the consistency of parent and self-report assessments of emotional symptomatology, and to further evaluate the connection between the presence of ADHD symptomatology and the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in these populations.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited from multiple sources, including patient advocacy group conferences (Noonan Syndrome Foundation and Minnesota Neurofibromatosis Symposium), postings within patient newsletters and social media sites, and at the outpatient genetics or neurofibromatosis specialty clinics at the University of Minnesota. Families with at least one child with NS or NF1 and their unaffected siblings were invited to participate, with a maximum of two children per family allowed to enroll. Children ranged in age from 8 to 16 years old (M = 11.9 years, SD = 2.6 years) at the time of assessment. Parents and children completed several questionnaires to assess the child's emotional, social, and behavioral functioning. Only families with spoken and written English language fluency were enrolled in the study, as not all study measures and procedures were available in other languages. Written parental informed consent and child assent were obtained prior to completion of study questionnaires. The study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

The diagnosis of NF1 or NS was confirmed for all participants in the clinical groups through medical examination by a specialist and/or review of available clinical genetics reports. Genetic confirmation of the syndrome was available for most affected children. Twenty-five children with NF1 (64%) had confirmed mutations in the NF1 gene, and 34 children with NS (87%) had confirmed mutations in one of the genes associated with NS. A majority of those with NS had mutations in the PTPN11 gene (54%); other mutations included the SOS1 (10%), KRAS (8%), RAF1 (5%), SHOC2 (5%), SOS2 (3%), and MAP2K1 (3%) genes. In terms of inheritance patterns, more of the children with NF1 in this cohort (44%) had a parent who was affected as compared to the NS group (10%) and the sibling group (16%). None of the unaffected siblings had positive genetic testing for a RASopathy variant or met clinical diagnostic criteria, based on parent report. Enrollment included a total of 112 children, but data from two children were excluded from analysis (one child in the NF1 group had genetic testing after enrollment which revealed lack of a pathogenic variant in the NF1 gene; for another child with severe vision loss, many of the questionnaire items were deemed inappropriate). The final cohort included 39 children with NF1, 39 children with NS, and 32 unaffected siblings. The distribution of age and gender of the children was very similar across the three groups (Table 1).

| Neuro-fibromatosistype 1 (n = 39) | Noonan syndrome (n = 39) | Unaffected siblings (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant demographics | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Age of child | 11.95 (2.50) | 12.10 (2.70) | 11.74 (2.54) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Gender (% male) | 20 (51%)a | 16 (41%) | 17 (53%) |

| Medical complications | |||

| Preterm birth | 3 (8%) | 14 (39%) | 1 (3%) |

| Cardiac disease | 1 (3%) | 24 (62%) | — |

| Seizures | 3 (8%) | 4 (10%) | — |

| Hydrocephalus | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | — |

| Chemotherapy treatment | 4 (10%) | — | — |

| Tumor/malignancy | |||

| Optic pathway glioma | 3 (8%) | — | — |

| Other intracranial gliomas | 1 (3%) | — | — |

| Plexiform neurofibroma | 4 (10%) | — | — |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | 1 (3%) | — | — |

| Other neurofibromas | 4 (10%) | — | — |

| Prescription medication type | |||

| No medications | 22 (56%) | 12 (31%) | 28 (88%) |

| Allergies/asthma | 4 (10%) | 9 (23%) | 1 (3%) |

| Focus/ADHD | 8 (21%) | 8 (21%) | 3 (9%) |

| Mood/sleep | 6 (15%) | 4 (10%) | — |

| Growth | 2 (5%) | 14 (36%) | — |

| Seizures | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | — |

| Migraines | 1 (3%) | 2 (5%) | — |

| Tics | 1 (3%) | — | — |

| Thyroid | — | 3 (8%) | — |

| Ulcerative colitis | — | 2 (5%) | — |

| Cardiac | — | 5 (13%) | — |

| Pain/nausea | — | 4 (10%) | — |

- a Cohort includes one individual identified as transgender.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 The Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition

The Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2) is a well-validated broadband scale of emotional and behavioral functioning (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). Caregivers completed the Parent Rating Scale (PRS), while children completed the Self-Report of Personality (SRP) forms. Items vary slightly based on the age of the individual being rated; the child (ages 8–11) and adolescent (ages 12–16) forms were used in this study. The BASC-2 PRS measures symptoms across several different clinical scales (Table 2), including Aggression (tending to behave in a hostile manner), Anxiety (acting nervous, fearful or worried), Attention Problems (tendency toward distractibility and concentration problems), Atypicality (behaving in ways that are unusual or associated with psychosis), Conduct Problems (engaging in antisocial and rule-breaking behavior), Depression (feeling unhappiness, sadness, and stress), Hyperactivity (tending to be overly active, rush, act without thinking), Somatization (tending to be overly sensitive to and complain about minor physical issues), and Withdrawal (evading others to avoid social contact). Standardized scores (T-scores) of 60–69 indicate the at-risk range, while T-scores of 70 or higher indicate scores in the clinically significant range. The SRP produces T-scores on the Anxiety, Attention Problems, Atypicality, Depression, and Hyperactivity subscales as well as five additional scales: Attitude to School (negative attitude toward school), Attitude to Teachers (negative attitude toward teachers), Locus of Control (low sense of control), Social Stress (high level of stress in social situations), and Sense of Inadequacy (high number of feelings of inadequacy). Subscales related to adaptive functioning are also available on the BASC-2, but were not reported as they were considered outside the scope of the research questions explored in the present analysis.

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 (n = 39) | Noonan syndrome (n = 39) | Unaffected siblings (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BASC-2 parent report subscale | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Hyperactivity | 59.1 (10.8)*** | 61.5 (14.5)*** | 48.8 (10.6) |

| Aggression | 51.4 (8.6) | 51.8 (12.8) | 46.5 (6.3) |

| Conduct problems | 52.3 (9.2) | 53.0 (10.8) | 48.6 (8.2) |

| Anxiety | 58.0 (13.2)** | 55.6 (9.3)** | 58.0 (12.4)** |

| Depression | 59.8 (13.4)*** | 58.9 (11.6)*** | 52.2 (10.7) |

| Somatization | 59.2 (15.7)** | 57.9 (11.0)*** | 51.7 (14.5) |

| Atypicality | 60.5 (14.8)*** | 58.4 (13.8)*** | 47.5 (7.1) |

| Withdrawal | 61.6 (12.8)*** | 60.8 (15.7)*** | 53.8 (14.4) |

| Attention problems | 57.2 (8.7)*** | 56.0 (11.0)** | 47.5 (9.8) |

| NF1 (n = 36) | Noonan syndrome (n = 36) | Unaffected siblings (n = 32) | |

| BASC-2 child report subscale | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Attitude to school | 47.8 (11.0) | 48.6 (11.9) | 46.9 (9.9) |

| Attitude to teachers | 43.6 (6.9) | 45.8 (8.3) | 46.6 (9.3) |

| Atypicality | 50.3 (10.4) | 50.0 (9.5) | 47.7 (6.1) |

| Locus of control | 49.2 (8.1) | 50.8 (10.4) | 48.9 (8.8) |

| Social stress | 48.5 (10.2) | 46.1 (8.1) | 46.3 (5.4) |

| Anxiety | 50.4 (10.6) | 51.0 (10.4) | 51.4 (7.5) |

| Depression | 47.7 (7.8) | 47.5 (8.2) | 45.5 (4.9) |

| Sense of inadequacy | 49.9 (6.7) | 49.9 (7.8) | 48.4 (7.6) |

| Attention problems | 53.9 (10.2)* | 51.2 (9.6) | 49.3 (9.1) |

| Hyperactivity | 52.0 (10.1) | 53.3 (9.8) | 51.6 (9.3) |

- Note: BASC-2 = Behavior Assessment Scale for Children, Second Edition. Asterisks denote significant results of one-sample t-tests comparing group means for each scale with normative population data. P-values for elevated (pathological) symptoms: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

2.2.2 ADHD Rating Scale

The ADHD Rating Scale, IV Edition (ADHD-RS) is an 18-item rating scale which assesses the presence and severity of nine inattentive and nine hyperactive/impulsive symptoms that constitute diagnostic criteria for ADHD, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This scale is widely used clinically and in research (DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998). Frequency of the 18 symptoms is rated on a scale ranging from “never or rarely” (0 points) to “very often” (3 points). ADHD symptom presentation for the current study was determined based on parent ratings of ADHD symptoms rated as “often” or “very often” per DSM-5 criteria.

2.2.3 Background history form

Each parent completed a background history form created by the research team, which asked parents to report information regarding children's age, gender, medical history (including medication use), previous mental health diagnoses, and family demographics.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were completed regarding demographic information and parent and child responses on the BASC-2. There were no missing data for parent report measures. BASC-2 self-report data were deemed invalid for three children with NF1 and three children with NS who were either unable to understand the forms (n = 5) or whose ratings indicated inconsistent responding on the validity scales (n = 1). Results from parent and child self-report ratings on the nine clinical subscales of this measure were compared to the normative population using one-sample t-tests. Mean differences and confidence intervals were also reported for intergroup comparisons. Pearson correlations were used to examine age-related trends and consistency across parent and child self-report ratings. Associations between parent and child ratings were possible in four domains, which measured similar constructs across both the parent and child BASC-2 forms: Anxiety, Depression, Attention Problems, and Hyperactivity. Both parent and child data were excluded from comparative analyses for the six participants with invalid self-report BASC-2 scores. Finally, independent sample t-tests were also used to examine differences in parent and child ratings of emotional functioning (Anxiety and Depression scales) in each of the two clinical groups and unaffected siblings group as a function of the presence of ADHD symptomatology.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Medical history

Information regarding medical complications and current medication use was examined based on the background history form completed by parents. Presence and treatment of tumors was observed only in the NF1 group (Table 1). Cardiac disease and premature birth were more common in children with NS than in the other groups. Fewer prescription medications were being used by children with NF1 (44%) and unaffected siblings (12%) as compared to children with NS (69%). Use of medications for ADHD-related concerns (dexmethylphenidate, guanfacine, methylphenidate, atomoxetine, lisdexamfetamine, and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine) was reported for 21% of children with NF1 and 21% of children with NS, whereas 9% of unaffected siblings were prescribed these medications at the time of the study. Medications to target mood, anxiety, and/or sleep-related concerns (bupropion, clonidine, risperidone, oxcarbazepine, fluoxetine, sertraline, trazadone, buspirone, and citalopram) were being taken by 15% of children with NF1 and 10% of children with NS. None of the unaffected siblings was prescribed mood-related medications. In terms of previous mental health diagnoses, parents of nine children with NF1 (23%), seven children with NS (18%), and one unaffected sibling (3%) indicated that their child had ever received a diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder.

3.2 Parent report of emotional and behavioral functioning

Ratings of emotional and behavioral functioning on the clinical scales of the BASC-2 for the NF1, NS, and the unaffected sibling groups are reported in Table 2. Parents who completed these measures rated children with NF1 and NS as having greater problems as compared to the normative population across all subscales except two of the externalizing scales (Aggression and Conduct Problems). In contrast, parent ratings for the unaffected sibling group were generally equivalent to the normative sample, with the exception of the Anxiety subscale, which indicated elevated symptoms in the sibling group compared to same-aged peers. The age of the child was not associated with any of the nine BASC-2 PRS subscales in the NS group or the sibling group. For the NF1 group, fewer Attention Problems (r = −.35, p = .03) and externalizing symptoms (Aggression: r = −.39, p = .01; and Conduct Problems: r = −.36, p = .03) were reported by parents in older children relative to younger children with NF1.

To evaluate parent-rated internalizing symptoms in children with RASopathies compared to their unaffected siblings, intergroup comparisons for the Anxiety and Depression subscales of the BASC-2 were completed. For the Anxiety scale, parent ratings did not reliably differ between the NF1 and sibling groups, mean difference = 0.0 (95% CI: −6.1 to 6.1). Parent ratings for Anxiety also did not reliably differ between the NS and sibling groups, mean difference = −2.4 (95% CI: −7.5 to 2.8). For the Depression scale, parent ratings in both syndrome groups were higher than their unaffected siblings: NF1 group mean difference = 7.6 (95% CI: 1.8–13.5); NS group mean difference = 6.7 (95% CI: 1.4–11.9). Across the two clinical groups, ratings from parents of children with NF1 were not significantly discrepant from those with NS for scores on either the Anxiety scale, mean difference = −2.4 (95% CI: −7.5 to 2.8), or the Depression scale, mean difference = −0.9 (95% CI: −6.6 to 4.7).

3.3 Child and adolescent self-report of emotional and behavioral functioning

Ratings by children and adolescents with and without RASopathies yielded results that were generally consistent with normative data. Although self-report ratings among children with NF1 yielded higher reporting of Attention Problems, no other self-report subscale means were elevated relative to the normative sample for the clinical or unaffected sibling groups. Specific correlations were calculated for the four subscales, which overlap the parent and child rating forms. Parent ratings across all groups were significantly correlated with child self-report ratings across groups: Anxiety (r = .37, p < .001), Depression (r = .49, p < .001), Hyperactivity (r = .33, p = .001), and Attention Problems (r = .51, p < .001). Despite the fact that most self-report ratings were below the threshold of clinical significance, self-report scores nevertheless moderately correlated with parent ratings of behavior.

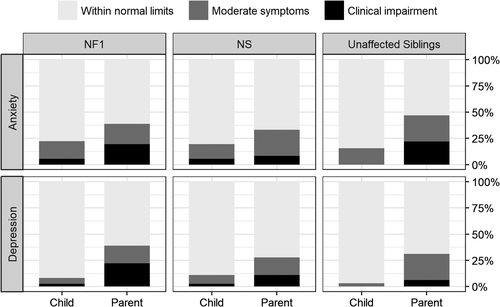

3.4 Clinical significance of internalizing symptomatology

Ratings of anxiety and depression symptoms were available on both parent and child-report forms. Parent ratings across all groups in this study were generally indicative of higher symptom severity than child ratings for both anxiety and depressive symptoms (Figure 1). For anxiety symptoms, approximately half of parents in both clinical groups rated their children as having symptoms that were outside of normal limits. Notably, unaffected siblings were also rated by their parents as having elevated frequency and severity of anxious symptomatology relative to the normative population. Several of the parent ratings for unaffected siblings indicated a severe level of anxiety (clinically significant range; defined as >2 SD from the normative mean score), even though no children from this group rated themselves as having severe symptoms. In terms of depressive symptoms, about one-third of children in each group had scores outside of normal limits based on parent report. The proportion of children rated in the clinically significant range was higher in the clinical groups than in the unaffected sibling group. Child self-report ratings of depression across all three groups were minimal overall.

3.5 Medical complications and emotional functioning

Due to sample size limitations, it was not possible to comprehensively assess the relationship between disease severity and emotional distress. A few medical complications were present in at least one-third of the children in one of the clinical groups (Table 1). In the NF1 group, this included the presence of clinically significant tumors (i.e., tumors causing functional interference with a child's daily activities and/or requiring medical intervention). In the NS group, this included preterm birth (prior to 37 weeks gestation) or presence of some form of cardiac disease requiring regular monitoring. For each of these symptoms, parent ratings of anxiety and depression symptoms are reported for those with the medical complications as well as those without (Table 3). There were no reliable differences in parent ratings of internalizing symptoms based on the presence or absence of these medical complications, although internalizing symptoms were slightly more common in children with NS who were born prematurely.

| BASC-2 anxiety | BASC-2 depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| NF1 cohort | ||

| Tumors, any type (31%) | 55.8 (13.9) | 58.8 (13.9) |

| No tumors (69%) | 59.0 (12.9) | 60.3 (13.3) |

| NS cohort | ||

| Preterm birth (39%) | 57.7 (12.3) | 61.5 (13.7) |

| No preterm birth (61%) | 54.7 (6.7) | 57.8 (9.7) |

| Cardiac disease (62%) | 55.8 (9.6) | 59.0 (8.9) |

| No cardiac disease (38%) | 55.3 (9.1) | 58.5 (15.2) |

3.6 Familial inheritance and emotional functioning

To examine whether having a parent who also had a RASopathy was likely to impact emotional functioning, we compared ratings of children's anxiety and depression symptoms among families in which a parent was also confirmed to be affected with the same syndrome relative to ratings of children in which neither parent had a known RASopathy. Due to the smaller number of children in the NS group who had an affected parent (n = 4), this comparison was only examined for the NF1 group. Among the 17 children with NF1 who had a parent with NF1, ratings of depression symptoms were approximately 9 points higher as compared to ratings of the 22 children with NF1 who did not have an affected parent (Table 4). Average ratings of depression symptoms were particularly high for the seven children with familial NF1 when the questionnaires were completed by parents with an NF1 diagnosis (T-score: M = 69.4, SD = 13.9) as compared to the 10 children with familial NF1 whose questionnaires were completed by an unaffected parent (M = 61.9, SD = 16.1), although statistical power was not adequate to conduct a robust comparison within this subgroup.

| Parent diagnosed with NF1 | Unaffected parent | Mean difference | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 17 | n = 22 | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Parent-report | ||||

| BASC-2 anxiety | 58.3 (15.0) | 57.8 (11.9) | 0.5 | −8.2 to 9.2 |

| BASC-2 depression | 65.0 (15.2)* | 55.8 (10.3) | 9.2 | 0.9 to 17.5 |

| Parent diagnosed with NF1 | Unaffected parent | Mean difference | 95% CI | |

| n = 16 | n = 20 | |||

| Child self-report | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| BASC-2 anxiety | 51.0 (9.5) | 49.8 (11.6) | 1.3 | −6.0 to 8.6 |

| BASC-2 depression | 49.8 (7.1) | 46.1 (8.2) | 3.7 | −1.6 to 8.9 |

- Note: BASC-2 = Behavior Assessment Scale for Children, Second Edition. Asterisks denote significant results of independent-sample t-tests comparing subgroup means on these scales based on whether or not children with NF1 also have an affected parent with NF1.

- *p < .05.

3.7 Associations between ADHD symptomatology and emotional functioning

Attention problems are highly comorbid with NF1 and NS, which was confirmed by notable elevations on BASC-2 scales measuring attention problems and hyperactivity. ADHD symptomology was also measured by parent ratings on the ADHD-RS, which follows DSM-5 symptom criteria. Based on the ADHD-RS, 39% of children with NF1 and 33% of children with NS met symptom criteria for ADHD, while only 13% of unaffected siblings met criteria (Table 5). Across all three groups, a little more than half of the children (50–62%) who met symptom criteria for ADHD exhibited significant hyperactivity/impulsivity, whereas the remaining children had predominately inattentive symptoms. Independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine parent-rated severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms as a factor of ADHD symptomology. Parent ratings of anxiety and depression were higher among children with NS who had met ADHD symptom criteria on the ADHD-RS than those without significant ADHD symptoms (Table 5). A similar pattern was seen in the NF1 group, with higher ratings of internalizing symptoms among those who also had ADHD symptoms, but this difference was not statistically significant. Parent ratings for the unaffected sibling group indicated higher levels of depressive symptoms among children who met criteria for ADHD.

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | Noonan syndrome | Unaffected siblings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD symptomsa | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| n = 24 | n = 15 | n = 26 | n = 13 | n = 28 | n = 4 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Parent-report | ||||||

| BASC-2 anxiety | 55.9 (10.2) | 61.4 (16.7) | 52.3 (7.2) | 62.3 (9.8)** | 57.3 (12.5) | 62.8 (11.9) |

| BASC-2 depression | 57.0 (11.7) | 64.4 (15.0) | 54.0 (7.2) | 68.5 (12.7)** | 49.9 (8.7) | 68.3 (10.2)** |

| Child self-report | ||||||

| BASC-2 anxiety | 50.5 (10.2) | 50.2 (11.4) | 48.3 (9.0) | 56.7 (10.9)* | 50.8 (7.0) | 55.5 (10.6) |

| BASC-2 depression | 47.4 (8.2) | 48.2 (7.5) | 46.1 (6.2) | 51.4 (11.0) | 44.9 (4.2) | 50.3 (7.2)* |

- *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

- a ADHD symptoms: Children were classified as meeting DSM-5 criteria for ADHD (+) or not meeting criteria (−) based on parent report on the ADHD Rating Scale, Fourth Edition. BASC-2 = Behavior Assessment Scale for Children, Second Edition. Asterisks denote significant results of independent-sample t-tests comparing subgroup means for each clinical (ADHD vs. no ADHD) on these scales.

Children who were rated by their parents to have significant ADHD symptoms also tended to rate themselves as having greater emotional symptoms. Children with NS endorsed higher symptoms of anxiety in the presence of ADHD symptoms than when an ADHD presentation was not indicated. Similarly, depression symptoms were more prevalent in unaffected siblings with clinical levels of ADHD symptoms, even if these ratings were not significantly higher than expected relative to normative data.

4 DISCUSSION

This study compared ratings of emotional and behavioral functioning of children with two relatively common genetic syndromes and their unaffected siblings. NF1 and NS both arise from disruptions to cellular signaling within a shared biochemical pathway, but they differ considerably in terms of their predominant medical features. Results derived from parent ratings confirm previous reports indicating that children with these conditions are at heightened risk for behavioral health issues. Past research using broadband parent- and teacher-report scales has frequently found that problems tend to be most evident on scales measuring attention problems and social problems (Cipolletta, Spina, & Spoto, 2018; Descheemaeker, Ghesquiere, Symons, Fryns, & Legius, 2005; Loitfelder et al., 2015; Pierpont, Tworog-Dube, & Roberts, 2015). These important behavioral concerns have been the focus of increasing research interest, although the volume of studies to date has been significantly greater for NF1 than for NS.

With regard to ADHD symptomatology, increasing evidence now supports the view that difficulties with inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity arise from the neurodevelopmental effects of the genetic pathology in some affected individuals (Green, Naylor, & Davies, 2017). Cohort studies that include an unaffected sibling group, including the current study, have repeatedly found that children with NF1 or NS demonstrate notably higher rates of ADHD symptoms relative to the general population as well as relative to their siblings who are raised in a similar environment but do not have the genetic syndrome (Dilts et al., 1996; Hyman, Shores, & North, 2005; Pierpont et al., 2015). Results of the current study suggest that ADHD symptoms are generally equivalent in terms of frequency and severity across the clinical groups. We observed similar findings across groups when considering multiple parameters, including mean scores on the BASC-2 Attention Problems and Hyperactivity subscales, the percentage of children who met symptom criteria for ADHD based on parent report (i.e., ADHD-RS), and the number of children in each clinical group who were taking ADHD-related medications. Social challenges were also apparent within the sample (e.g., parent ratings indicated elevations on the Withdrawal scale, which measures children's tendencies to have difficulty making friends, avoid others or prefer to be alone). These social challenges have been more thoroughly explored using focused measures of social development and social competence both in the current cohort (Pierpont et al., 2018) and in other groups of children and adults with RASopathies (e.g., Eijk et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2017; Lewis, Porter, Wiliams, North, & Payne, 2016; Plasschaert et al., 2015; Walsh et al., 2013).

While attention-related and social difficulties may be the most prevalent behavioral challenges in RASopathies, our results suggest that internalizing symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and physical complaints also constitute an area of vulnerability. Greater frequency and severity of internalizing symptoms as compared to externalizing symptoms has been a common theme in studies of RASopathies (Allen et al., 2016; Coutinho et al., 2017; Graf et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2012). Therefore, analyses in the current study focused on developing a better understanding of the nature of these internalizing symptoms, particularly symptoms of depression and anxiety.

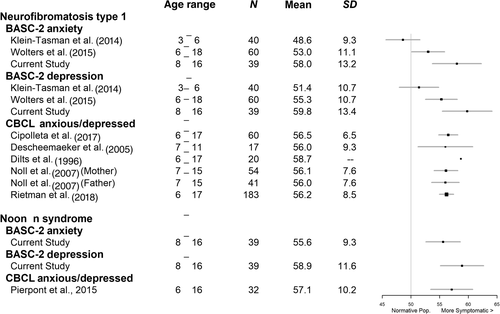

To illustrate our findings within the context of previous literature, results from the scales measuring anxiety and depression symptomatology were plotted in Figure 2 relative to observations from other studies that utilized broadband parent-report questionnaires that assessed these symptoms, including the BASC-2 or the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Consistent with our study, nearly all studies have found heightened symptoms of anxiety and depression for these clinical groups relative to the normative sample mean. However, the present investigation contains slightly higher mean scores than most studies. This moderately higher magnitude of internalizing symptoms in our cohort as compared to past studies could be related to a few factors, including sample characteristics or differences in psychometric properties of the measures used (BASC-2 vs. CBCL). The most apparent discrepancy in scores on anxiety and depression measures across studies appears to be between our study and that of Klein-Tasman et al. (2014), which enrolled preschool-aged children with NF1 (ages 3–6). Klein-Tasman and colleagues found no significant parent-rated group mean differences between the NF1 group and a typically developing comparison group for anxiety or depressive symptomatology on the BASC-2. This sample was notably younger than our current cohort, which may account for the differences in the frequency and severity of internalizing problems. Research indicates that the mean age of onset of depressive disorders occurs between 11 and 14 years old; the mean age of onset of anxiety symptomology tends to vary based on the subtype of anxiety, with the earliest mean age of onset (i.e., separation anxiety and specific phobias) occurring in middle childhood and more generalized forms occurring later (Merikangas, Nakamura, & Kessler, 2009). Hence, it might be expected that greater symptoms of depression and anxiety would be apparent in our somewhat older cohort.

Important to our central question of how emotional and behavioral functioning is associated with RAS pathway dysregulation, findings from the current study demonstrated a similar pattern of symptom endorsement for children with NF1 and with NS. Specifically, scores on anxiety and depression scales were outside the normative range for almost half of each clinical group, with varying degrees of impairment noted within each subgroup. Past research on NS has reported a frequency of clinically elevated symptoms of anxiety/depression of somewhere between 16 and 32% (Alfieri et al., 2014; Pierpont et al., 2015). The current results corroborate earlier studies reporting that many children with RASopathies have “subclinical” symptoms based on questionnaire measures that may not be severe enough to warrant a diagnosis (e.g., Perrino et al., 2018), but may nevertheless impact a child's well-being.

An important aim of this study was also to understand how parent and child perspectives of emotional and behavioral symptomatology were reflected in their ratings on widely used behavioral questionnaires. Notably, while ratings by children and their parents in this study were correlated, they also diverged significantly in terms of the severity of the symptoms reported. Parents in the study rated their children as having significantly greater symptomatology than children reported in their self-ratings. This finding is consistent with other studies of children with NF1 (Krab et al., 2009; Rietman et al., 2018), as well as research that has looked more broadly at children with chronic illness and also healthy children with a sibling with chronic illness (Sharpe & Rossiter, 2002).

Parents of children with a chronic disease may view their child(ren) as especially vulnerable, or may be overly sensitive to negative outcomes, thus overestimating symptomatology (Anthony, Gil, & Schanberg, 2003). Conversely, it may be that parents' insights of their children are fairly accurate, but that children in these scenarios have less insight into their own behaviors and emotions than adults do. Children with neurodevelopmental disorders, who often have co-occurring difficulties with social cognition and insight, may be particularly apt to under-report symptoms or to tend to try to respond the way they think people want them to rather than accurately reporting their symptoms. For example, Verhoeven, Wingbermuhle, Egger, Van der Burgt, and Tuinier (2008) remarked that individuals with NS in their study were “in general remarkably friendly, cooperative and very willing to please. These are all aspects of a social[ly] desirable attitude” (p. 194). This tendency to respond in a socially desirable manner may have resulted in children with NS tending to endorse fewer symptoms of distress as compared with ratings by their parents.

Among our NS cohort, parent ratings of anxiety symptomatology indicated clinically significant symptoms in 8% of the sample and moderate elevations (subclinical anxiety) in 26%. This rate is closely matched to the frequency of anxiety reported in a recent study that utilized diagnostic evaluations, which reported rates of 8% and 30% for clinical and subclinical levels of anxiety, respectively (Perrino et al., 2018). In contrast to parent ratings, child self-report measures in our study only revealed rates of 5% (clinical) and 14% (subclinical). Notably, we observed that some children appeared to have poor patience/focus when completing the questionnaires, and may have rushed through them in an attempt to complete them rapidly. Furthermore, some of the questions on the BASC-2 seemed too broad or vague for children to identify with them. Another research group that used an anxiety-specific self-report questionnaire reported that children with NF1 rated themselves as having significantly higher anxiety than children from the community without NF1 (Pasini et al., 2012). Thus, when working with children with RASopathies, it may be important that any self-report measurement tools pose questions that are highly relatable to daily life or more focused on concrete, specific behaviors.

Assuming that parents and teachers are fairly accurate raters of children's difficulties, how do we understand the sources of heightened emotional difficulties in children with RASopathies? While we did not observe a consistent association between major medical complications (e.g., presence of tumors, cardiac disease) and emotional symptomatology in this cohort, our results do suggest the possibility that prematurity is a risk factor for difficulties with emotion regulation, which is consistent with the literature on neurodevelopmental effects of preterm birth (Cassiano, Gaspardo, & Linhares, 2016; Clark, Woodward, Horwood, & Moor, 2008). Previous work has found an association of preterm birth and other birth complications with lower adaptive functioning and increased behavior problems in children with NS and other RASopathies (Pierpont et al., 2010; Pierpont & Wolford, 2016). More broadly, anxiety has been found to have a modest correlation with the severity of disease in children with NF1, but this was not tied to the visibility of physical symptoms (Pasini et al., 2012). It is clear that the severity of physical clinical manifestations of the disease does not fully explain emotional challenges experienced by some children. Secondary experiences of medical involvement, such as pain interference, however, may have a more robust association with emotional symptoms in adolescents with NF1 (Wolters et al., 2015). We did not directly measure the extent of pain, but this is an area that is receiving increasing recognition as a problem interfering with quality of life in individuals with RASopathies (Leoni et al., 2019; Wolkenstein, Zeller, Revuz, Ecosse, & Leplege, 2001; Wolters et al., 2015), and should be examined more closely in future research.

Our study identified a robust association of emotional symptoms with other aspects of neurodevelopmental function in this cohort, specifically with ADHD symptomatology. In line with results from Mautner et al. (2002), we found that ADHD symptoms, especially in children with NS, seem to be associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety. This association suggests that severity of behavioral dysregulation may present a greater risk factor for emotional functioning challenges than the medical syndrome diagnosis itself, and is consistent with literature indicating increased emotional challenges among children with ADHD in the general population (Bowen, Chavira, Bailey, Stein, & Stein, 2008; Schatz & Rostain, 2006). There are several potential explanations as to why this pattern may exist. First, symptoms of anxiety and depression may arise from effects of altered brain connectivity or neurotransmitter function. Research has found widespread connectivity differences across various brain regions in individuals with NF1 that are associated with cognitive, social, and behavioral sequelae (Loitfelder et al., 2015). Alternatively (or additionally), it could be that children have internalized their experiences in school and other environments (e.g., experiences of struggling academically, not being accepted, or getting into trouble due to their behaviors), resulting in greater emotional challenges. Finally, in the current study, ratings of depressive symptoms tended to be higher among children with NF1 who had an affected parent than those without an affected parent. This finding further suggests that heritable neurobiological vulnerabilities may contribute to mood difficulties, or to the perception of these difficulties by their parents.

An unexpected finding of the current study was the fact that differences from the normative sample with respect to anxiety symptoms were found not only in the clinical groups, but also among unaffected siblings. Almost half of the children with NF1 and NS in the current study were rated by their parents as having symptoms of anxiety that were outside of normal limits. A similar pattern of symptomology was also found in the unaffected sibling group. This is one of the first studies that have noted increased anxiety among unaffected siblings of children with RASopathies. Although the source of anxiety among the unaffected siblings in this study is unclear, there is some research to suggest that internalizing behaviors, including anxiety and depression, are common among siblings of children with a chronic illness (e.g., Sharpe & Rossiter, 2002). While some studies have found siblings of children with neurodevelopmental disorders such as Williams syndrome (Leyfer, Woodruff-Borden, & Mervis, 2009) or ASD (Hastings & Petalas, 2014) to be at no greater risk of anxiety or internalizing problems than the general population, other research suggests that siblings of children with disabilities (e.g., ASD, cystic fibrosis, and cerebral palsy) may be at increased risk of depression symptoms (Breslau & Prabucki, 1987; Shivers, Deisenroth, & Taylor, 2013). Differences in methodology, severity of illness/disability associated with different conditions, and sibling age may help to explain these mixed results across studies. There is also some research to suggest that family-related variables, such as maternal history of anxiety, may predict higher anxiety symptoms in female siblings of children with disabilities (e.g., Shivers et al., 2013). Thus, potential explanations for sibling risk of internalizing symptoms include heritable, gender-based, and environmental risk factors.

4.1 Limitations

There are several methodological limitations that need to be considered. First, the majority of participants from the current sample were recruited from outpatient clinics and conferences devoted specifically to NF1 and NS. Thus, enrollment for this study may have trended toward families with greater need who were seeking support and services, as opposed to families with milder forms of these conditions. Second, it was not possible to obtain a large enough sample of children to conduct a matched case–control study where every affected child in the cohort had a matched sibling within the age range of the study; therefore, the unaffected siblings of children with NF1 and NS were included together in a single comparison group. Third, only those families who indicated spoken and written English language fluency were included, since foreign language translation and cultural influences could not be adequately controlled across all study measures and procedures. Fourth, it is unclear whether parents of children currently taking stimulant medications responded to the questionnaires based on their behavioral presentation on or off medication. Thus, current parent reports may be confounded with respect to medication status.

The source of the data for the current study is based on subjective reports provided by questionnaire-based measures, which can have notable limitations. Future studies may profit from including observational ratings, teacher rating scales, or structured interviews to determine more specific information regarding emotional functioning among children with NF1 and NS. Finally, differences in our study regarding severity of symptom endorsement compared to other studies may be attributable to discrepancies in psychometric properties between different measures used (e.g., BASC-2 vs. CBCL). Most previous studies of children with NF1 and NS have used parent ratings from the CBCL. As anxiety and depressive symptoms are assessed together in one subscale on the CBCL, the CBCL and BASC-2 may differ somewhat in terms of the underlying concerns that are being measured. The lack of consistency in types of comparison groups across studies (e.g., normative data, unaffected siblings, and healthy community samples) also limits generalizability across samples. Norm-referenced metrics, such as T-scores, allow researchers to quantify and detect differences in the sample groups from the general population without having to rely solely on the use of a control group. However, the psychometric properties of derived T-scores for some measures (i.e., the CBCL) are more ideal for clinical purposes than for research, and the manual for this measure recommends that raw scores be used in research studies to allow for inclusion of the full range of data (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Therefore, studies using the CBCL or combining data across instruments may benefit from comparing both T-scores and raw scores when conducting analyses using broadband behavioral and emotional measures.

4.2 Clinical implications

Research among children diagnosed with NF1 and NS has consistently identified difficulties related to attention problems and social deficits (Adviento et al., 2014; Green et al., 2017; Noll et al., 2007; Pierpont et al., 2018). Results of the current study emphasize the need for further examination of internalizing symptoms among individuals with RASopathies, especially in children with a comorbid ADHD diagnosis. Furthermore, our study illuminates the need for multiple raters when assessing overall emotional functioning, as identification of emotional difficulties based on self-report alone can be unreliable and is not sufficient. Other sources of information, including parent and teacher reports, provide important perspective on the child's functioning. It may also be helpful to use shorter questionnaires with clear, simple language and to have the examiner remain nearby to answer questions and assess the child's understanding of items. Additionally, conducting interviews within a clinic setting may be beneficial, as our observational experience was that child participants with NF1 or NS who have come through clinic as part of an evaluation have disclosed more symptoms during interview with a mental health provider as compared to their self-ratings on the questionnaire.

As previously indicated, frequency and severity of emotional difficulties reported among children with RASopathies differs substantially across studies. Findings of the current study and previous research suggest that these variations can be due to differences in rater, the specific measure used, and potentially the age of the participants. Because studies of individuals with NF1 and NS have reported less pronounced self-report symptom endorsement and weaker emotion recognition skills among affected individuals, the level of impairment with respect to emotional functioning may be underreported. Therefore, even if symptomology appears to be mild or subclinical, treatments and interventions targeted at addressing these concerns may still be warranted. Research on the efficacy of interventions that target emotional functioning in children with RASopathies will be important, as well as consideration of pharmacotherapy options. A combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy treatments may be considered best practice for addressing moderate to severe anxiety and depression.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The current study found that parent ratings of emotional functioning were outside the normative range for almost half of the children with NF1 or NS. Consistent with previous research, children in both clinical groups were rated by their parents as having greater problems as compared to the normative population across most areas of emotional and behavioral functioning, except externalizing problems (e.g., acting in an overly aggressive or antisocial manner). Overall parent ratings in this study were generally indicative of higher symptom severity as compared to self-report results. While child ratings were minimal overall, parent ratings across all groups were significantly correlated with child self-report ratings. This finding suggests that while children may endorse fewer symptoms than indicated by their parents' observations, they may have some insight that these symptoms exist. Intergroup comparisons of emotional functioning allowed for novel findings in the current study, which revealed that higher parent reporting of depressive symptoms appears to be unique to the children with RASopathies, whereas high rates of anxiety were found across both the clinical groups and unaffected siblings. As higher rates of depressive symptoms were endorsed among children with a RASopathy, especially those with an affected parent, these symptoms may be related to neurobiological changes as a result of RAS-MAPK pathway-related mutations.

While parent reporting of internalizing symptoms in their children with RASopathies did not significantly differ based on the presence or absence of the more commonly associated medical complications (e.g., tumors, cardiac problems), there were differences noted based on the presence or absence of ADHD symptoms. Parent ratings of anxiety and depression were generally higher among children who had notable ADHD symptoms than among those without ADHD symptoms. As symptoms of ADHD may be more recognizable, at least at younger ages, than internalizing symptoms, future research may examine whether there is a decrease in internalizing problems in children with RASopathies who participate in early intervention to manage ADHD-related symptoms. Children with RASopathies, even those with subclinical symptoms, may benefit from referral to mental health providers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express gratitude to the children and their families who participated in the research. Support for this study was provided by a University of Minnesota Department of Pediatrics fellowship award to the second and last authors, as well as a gift from the NF Midwest and NF Upper Midwest Foundations. Research reported in this publication was also supported by NIH Grant P30 CA77598 utilizing the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core shared resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.H., M.S.C., C.M., and E.P. conceptualized the study and developed the study design. R.H., A.F., M.E.P., S.B., K.S., C.M., and E.P. participated in the acquisition of data. The initial draft of the manuscript was written by A.M. and E.P. A.M., R.S., and E.P. completed statistical analysis and drafting of figures. All authors edited and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the authors.