Short rib syndrome Beemer–Langer type, a short history

To the Editor:

I read with sincere interest and enthusiasm the article by Silveira, Morena, and Cavalcanti 2017) in the May issue of the Journal (2017). Seeing the article led me to recollect the original family that we reported on in the cited paper (Beemer et al., 1983).

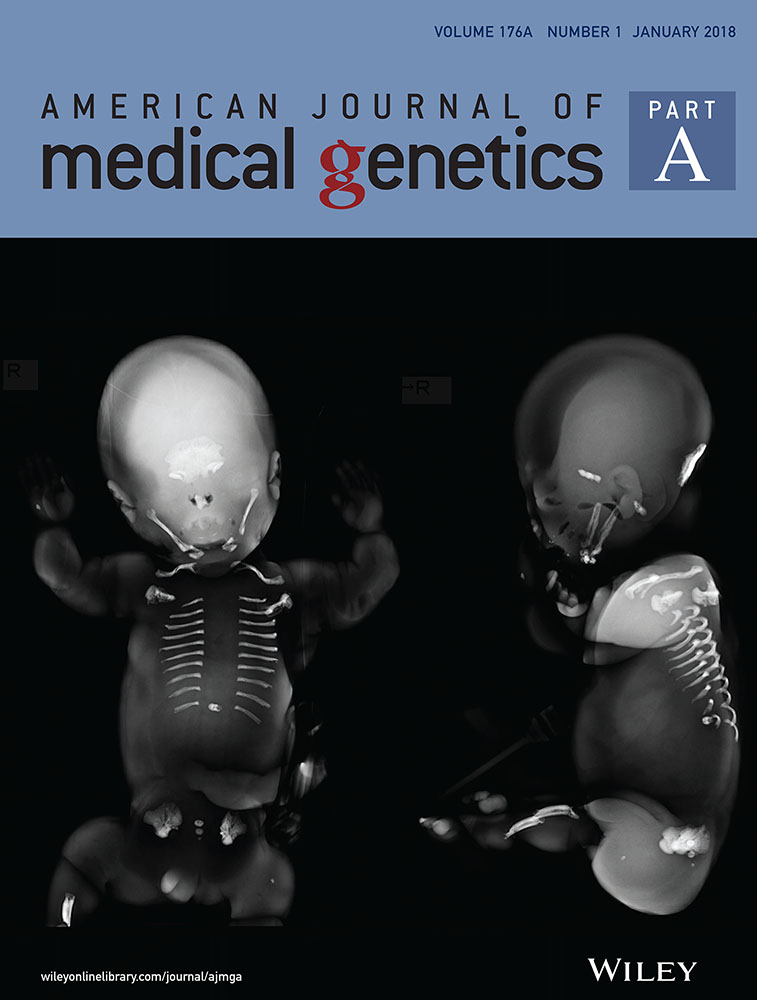

In 1980, the postmortem photographs and radiographs of a boy were sent to our Center by the pediatrician in charge for diagnosis. The main features were generalized hydrops, dysmorphic facial features with median cleft lip and cleft palate, very narrow thorax, protuberant abdomen and short, bowed limbs with ambiguous external genitals. Radiographs revealed very short horizontal ribs, high clavicles and broad, and flattened vertebrae. There was no polydactyly. The long tubular bones—with the exception of the tibiae were very short and bowed. The metaphyses of the long bones did not show the irregularities as described before in short rib- polydactyly syndrome (SRPS) Majewski-type. In a subsequent pregnancy ultrasound studies at 19 weeks revealed similar femoral and costal anomalies as in the elder sibling; the parents opted for termination of the pregnancy. The female fetus showed the same signs as described in the first child.

What about the diagnosis? The clinical and radiological features looked like those of short rib- polydactyly (SRP) Majewski type. But a main feature of that syndrome, polydactyly, was not present in our cases. At that time most authors distinguished three types of SRP syndromes: Saldino–Noonan or type 1, Majewski type or type two, and Verma–Naumoff type or type 3. However other authors distinguished only two SRP types: Majewski type and non-Majewski type. But we thought that not all features fit into one of the types already known from literature. Neither was the case for asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia (Jeune syndrome) or with chondroectodermal dyplasia (Ellis–van Creveld syndrome). So we considered it to be a possibly “new” syndrome.

Practicing clinical genetics—like other professions—is often a matter of cooperation and consultation, and that was certainly so in those days. In the pre-internet days, traveling moved things ahead and made discussions more easy. So I did present the data at various meetings, starting nationally of course. Preliminary conclusions: possibly “new”. One of the first international meetings where I did present the data was the 1981 March of Dimes 14th Annual Meeting in San Diego, California (USA). At that and other meetings I could discuss the clinical and radiographic data with quite a number of experienced professionals, who all were very helpful. One of them was Dr. Leonard Langer who happened to know an almost identical patient. With contributions of several other authors, Dr. Langer and I wrote a paper on our cases and concluded that our data might constitute a “new” syndrome (Beemer et al., 1983) . It was at the time that a purely clinical paper could still be published and was in fact the only way to make newly recognized syndromes public. In a later year, I did visit Dr Langer at his office in Greenwood, South Carolina.

I could also present our data at the 3rd Symposium on Clinical Genetics in Pediatrics (Klinische Genetik in der Paediatrie) in Kiel, Germany, organized by Drs. Tolksdorf and Spranger and discussed the data with the latter author. And of course I paid a visit to Dr. Majewski who in fact lived relatively nearby in Germany.

This was the way things went in these “old” days: you tried to give an as extensive and precise as possible description of the clinical, radiographic, and other relevant features. Then you discussed these data with experts in the relevant fields and tried to meet them personally. For me at least that way of “delineating a syndrome” worked well, about 30 years ago: I liked meeting experts in person. Of course you hope someone will read the paper you and your coauthors wrote about it, remember and publish identical cases, and refer to yours. And, of course, attaches (amongst others) your name to that particular possibly “new” syndrome. And these days another, important, phase in the natural course of a syndrome has been reached: finding a causative gene. Congratulations!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wish to thank the late Jan B. Bijlsma, MD. (clinical geneticist) for substantial help in the diagnostic process and A.M. Hemmes, MD. (pediatrician) for referral of the index patient.