In this issue

Limb defects often accompanied by other problems

A relatively high proportion of children with congenital limb deficiencies need thorough evaluations because they also have other anomalies, write Bedard et al (p. 18, DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38513).

The researchers analyzed Alberta (Canada) Congenital Anomalies Surveillance System data to determine both distribution of associated anomalies among congenital limb deficiency cases and malformation patterns for syndrome classification. The analysis included data on live births and stillbirths between 1980 and 2012 as well as statistics on early fetal deaths and terminations of pregnancies from 1997 to 2012 that involved a child or fetus with a congenital limb deficiency and at least one major congenital anomaly.

Of 170 cases identified, 75.3% were live born, 61.8% were male, 78.8% had longitudinal limb deficiencies, and 77.6% had associated anomalies outside the musculoskeletal system. The researchers found significant associations between preaxial limb defects and central nervous, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular system anomalies. Associations between postaxial longitudinal defects and congenital hip and foot abnormalities were also observed.

The researchers suggest possible and probable syndrome diagnoses for cases with recognized malformation patterns, including tibial agenesis, humero-radial synostosis, neural tube disorders and limb deficiencies, holoprosencephaly and limb defects, and other defects possibly caused by teratogens such as cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana.

As next-generation sequencing becomes more mainstream, the proportion of cases with unrecognized patterns of malformations will decrease because more will have had a genetic diagnosis, the researchers predict. They suggest that surveillance systems incorporate these diagnoses based on unrecognized patterns of malformation to aid accurate classification of cases.

PARENTS’ EDUCATION INFLUENCES IQS OF CHILDREN WITH DOWN SYNDROME

Despite obvious biological origins of intellectual impairments in children with Down syndrome (DS), familial factors play an important role in modulating their phenotypes, write Evans et al (p. 28, DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38519).

Recent research shows that variability among DS phenotypes is influenced by parental traits. In response, the researchers examined longitudinally the role of parental education as a proxy for parental intelligence as well as that education's influence on cognitive ability, measured at different points in development.

The researchers studied 43 children with DS who were 4 to 21 years of age and their parents. They determined mean education of both parents and measured their children's IQ with the Stanford- Binet 4th edition test at baseline and again 24 months later. The researchers divided the children into 2 age groups: 4 to 13 years of age for group 1 and 13 to 21 years of age for group 2.

The correlations between parental education and children's IQ scores were higher for group 2, with a mean r score of 0.46 versus a mean r score of 0.33 for group 2. Correlations between parental education and children's IQ increased over time, increasing from an r score of 0.26 to 39 for group 1 and from 0.49 to 46 for group 2.

These findings and previous research can inform expectations for how children with DS will develop, say researchers.

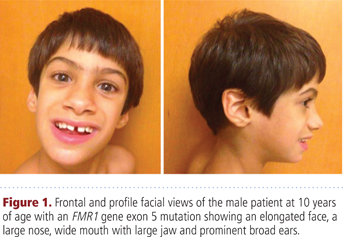

FRAGILE X SYNDROME PATIENT LACKS TYPICAL CGG REPEAT EXPANSION

Children who meet clinical criteria for fragile X syndrome (FXS) but whose test results do not show CGG repeats may have an atypical mutation in FMR1, write Sitzmann et al (p. 11, DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38504). The researchers describe an FXS patient with a rare FMR1 mutation previously reported in a single patient.

FXS is the most common inherited form of intellectual disability and is usually caused by FMR1 CGG-repeat expansions that prevent the gene's expression.

The 10-year-old child had a missense FMR1 mutation at c.413G>A but not the typical CGG-repeat expansion. He had classic FXS characteristics including intellectual disability, craniofacial findings, hyperextensibility, fleshy hands, flat feet, unsteady gait, and seizures. The child also had autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. These are more FXS features than those of the previously reported patient.

A literature review revealed that 20 individuals with rare missense or nonsense mutations or other coding disturbances of the FMR1 gene ranged in age from infancy to 50 years. Their mutations included deletions, splicing errors, missense, and nonsense mutations. All reported individuals had intellectual disability; most were verbal with limited speech and had autism and hyperactivity.

Four of the 20 individuals had a mutation within exon 15, 3 within exon 5, and 2 within exon 2.

The researchers suggest that children with FXS features but no CGG-repeat expansion receive other tests, including nextgeneration sequencing, to rule out FXS.