Additional report on Moreno-Nishimura-Schmidt overgrowth syndrome

To the Editor:

“Metaphyseal undermodeling, spondylar dysplasia, and overgrowth” (OMIM, 608811), “overgrowth syndrome with skeletal dysplasia” or “Nishimura–Schmidt endochondral gigantism” (Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2010 and 2015 revisions) is a distinctive overgrowth syndrome with excessive endochondral bone growth (Bonafe et al., 2015; Warman et al., 2011). An eponymous name “Nishimura–Schmidt endochondral gigantism” has been used because two groups independently demonstrated characteristic skeletal overgrowth and identified the syndrome (Bonafe et al., 2015; Nishimura et al., 2004; Schmidt et al., 2007). However, an affected individual had been reported 4 decades ago (Moreno, Zachai, Kaufmann, & Mellmann, 1974).

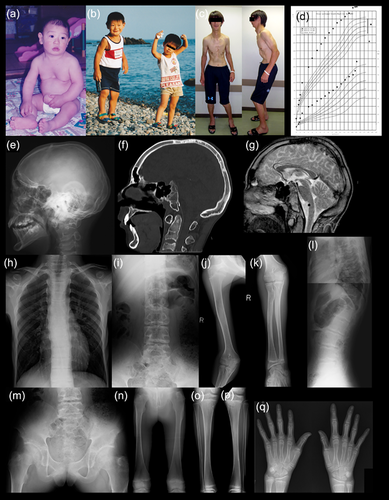

The disorder shows severe pre- and post-natal overgrowth and facial dysmorphism (sloping forehead, bitemporal narrowing, prominent supraorbital ridge, large ears, micrognathia, and occasionally deep-set eyes). Other physical features include hoarse voice, narrow thorax, long trunk, kyphoscoliosis, large hands and feet, joint contracture, loss of subcutaneous fat tissues, and umbilical hernia. The skeletal changes are characterized by thickened skull base, spondylar dysplasia, and broad metaphyses; bone age is not accelerated. Schmidt et al. (2007) demonstrated cartilaginous overgrowth in the skull base and spine on computed tomography (CT); therefore, they hypothesized that endochondral overgrowth (endochondral gigantism) is responsible for the phenotypes. The patient also showed suppressed GH-IGF axis. Here we report an additional patient and review the clinical and radiological findings in previously reported patients.

The patient was a Japanese boy born at 37 weeks of gestation. Birth length was 54.5 cm (+2.6 SD), birth weight was 4,108 g (+2.6 SD), and OFC was 35.0 cm (+1.2 SD). Somatic overgrowth and facial dysmorphism attracted medical attention in infancy. The facial dysmorphism included sloping forehead, bitemporal narrowing, prominent supraorbital ridge, large ears, and micrognathia (Figure 1). He also showed pectus excavatum and a large umbilical hernia that was repaired at 1 year of age. Other physical findings included a narrow thorax, long trunk, and large hands and feet. Mental development was normal. Somatic overgrowth increasingly accelerated during childhood. At age 14 years and 4 months, he was referred to us for evaluation. His height was 192.1 cm (+4.1 SD) and weight was 70.1 kg (+1.5 SD). He showed thoracic kyphosis, contracture of the large joints, limb asymmetry, and loss of adipose tissue mainly in the trunk. Puberty and bone age was mildly delayed (Tanner–Whitehouse method for bone age: 12 years, 8 months). Endocrinological assessment showed low IGF-1 Levels, and insulin provocative test showed prolonged hypoglycemia with delayed response of GH and cortisol (Supplemental material S1). Gonadotropin releasing hormone provocative test showed a prepubertal pattern. Head CT and brain MRI demonstrated cartilaginous overgrowth of the clivus (Figure 1). He underwent androgen therapy for 2 years. At 16 years and 10 months, his height was 209 cm (+6.7 SD) and weight was 102.7 kg (+4.0 SD). He had characteristic facial and physical features and hoarse voice. Progressive thoracic kyphosis required surgical intervention at 20 years. Skeletal survey at 14 and 20 years revealed thickened skull base, narrow thorax, spondylar dysplasia (megalospondyly, platyspondyly, and kyphoscoliosis), broad ilia with short greater sciatic notches, broad pubic, and ischial bones, metaphyseal broadening, and large epiphyses (Figure 1). Written informed consent for molecular analysis was obtained from the patient and his parents, and the molecular analyses were approved by the Ethics Committee of Keio University School of Medicine. We carried out whole-exome sequencing of genomic DNA of peripheral lymphocytes for the patient and his parents and did not identify pathogenic variant for a de novo autosomal dominant or recessive trait.

We summarize the clinical and radiological manifestations of the present patient and three previously reported patients in Table 1. We excluded patients 2 and 3 in Nishimura's original report (Nishimura et al., 2004) because the overgrowth and skeletal changes in these patients were too mild. The present patient showed less pronounced prenatal overgrowth compared with previously reported patients. He also had pectus excavatum and limb asymmetry that were not previously described. Otherwise, his clinical manifestations recapitulated previous reports. He showed suppressed GH-IGF axis, similar to the Schmidt's patient. In addition, he also showed prolonged hypoglycemia, poor cortisol response with insulin provocative test, and delayed puberty. Mild or subclinical endocrinological derangement could be an essential indicator of M-N-S syndrome.

| Moreno | Nishimura | Schmidt | Case1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | Term | 38 w | 34 w | 37 w |

| Birth length (cm) | 60 | 64.8 | 61 | 54.5 |

| (SD) | (+5.2) | (+6.6) | (+6.0) | (+2.6) |

| Birth weight (g) | 6,870 | 6,100 | 6,600 | 4,108 |

| (SD) | (+9.7) | (+7.2) | (+6.8) | (+2.6) |

| OFC at birth (cm) | 43 | 40 | 38.5 | 35 |

| (SD) | (+6.9) | (+4.3) | (+3.2) | (+1.2) |

| Height showing maximum SD (cm) (age) | ND | 188 (11yo) | 146 (3y6m) | 220 (18y) |

| (SD) | (+7.2) | (+11.7) | (+8.5) | |

| Weight (kg) | ND | 65, 11y (+6.5) | 39 (3y6m) | 100, 18y (+3.6) |

| OFC (cm) | ND | ND | ND | 60.5, 14y |

| Arm span (cm) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Sloping forehead | + | + | + | + |

| Bitemporal narrowing | + | + | + | + |

| Prominent supraorbital ridge | + | + | + | + |

| Deep-set eyes | + | − | + | − |

| Large ears | + | + | + | + |

| Micrognathia | + | + | + | + |

| Hoarse voice | + | + | + | + |

| Narrow thorax | ND | + | + | + |

| Long trunk | ND | + | + | + |

| Kyphoscoliosis | + | + | + | + |

| Large hands and feet | + | + | + | + |

| Joint contracture | + | + | + | + |

| Loss of fatty tissue | ND | + | + | + |

| Umbilical hernia | + | + | + | + |

| Other clinical features | Multiple fractures | Pectus excavatum, limb asymmetry, delayed puberty | ||

| Low IGF | ND | + | ++ | + |

| Thickened skull base | + | + | + | + |

| Short ribs | + | + | + | + |

| Spondylar dysplasia | + | + | + | + |

| Broad ilia with short greater sciatic notches | ND | + | + | + |

| Broad pubic and ischial bones | ND | + | + | + |

| Metaphyseal broadening | + | + | + | + |

| Large epiphyses | + | + | + | + |

| Advanced bone age | + | + | + | − |

The skeletal changes are so unique that radiological findings alone enable discriminating this condition from other overgrowth syndromes. The radiological constellation includes hyperostosis of the skull base, spondylar dysplasia (megalospondyly, delayed vertebral ossification leading to ovoid vertebral bodies, and coronal clefts), metaphyseal broadening, megaepiphysis, and broad ilia with short greater sciatic notches. Our radiological findings mostly recapitulate previous studies; however, they were milder and, bone age was delayed in our case instead of being advanced. This could possibly be explained by suppressed GH-IGF axis; however, in the previous report by Schmidt, the bone age was advanced despite the GH-IGF axis was suppressed. It remains unknown what contributed to these two different phenotypes. As suggested by Schmidt et al. (2007) we assume that these skeletal changes are caused by increased proliferation and impaired terminal maturation of chondrocytes. Loss of auto-regulation in endochondral bone growth may secondarily suppress the GH-IGF axis.

In summary, the clinical and radiological findings from the present patient and three previously reported patients corroborate the results by Moreno et al. (1974), Nishimura et al. (2004), and Schmidt et al. (2007) where this syndrome is associated with severe pre- and post-natal overgrowth with generalized skeletal dysplasia, possibly because of endochondral overgrowth. The current nosology for this syndrome, including metaphyseal undermodeling, spondylar dysplasia, and overgrowth (OMIM, 608811) and overgrowth syndrome with skeletal dysplasia (Bonafe et al., 2015; Warman et al., 2011) are too abstract and do not set it apart from other overgrowth syndromes. The alternative eponymous term Nishimura–Schmidt endochondral gigantism (Bonafe et al., 2015) captures the pathogenesis of the disorder; however, the name does not refer to Moreno's original report. In addition, the term gigantism may be offensive to the affected individuals. Therefore, we propose an eponymous term, Moreno–Nishimura–Schmidt overgrowth syndrome (M-N-S syndrome), as appropriate nosology.