Novel features of Helsmoortel–Van der Aa/ADNP syndrome in a boy with a known pathogenic mutation in the ADNP gene detected by exome sequencing

TO THE EDITOR

We read with interest the case report and review of Helsmoortel—Van der Aa syndrome (HVDAS), also known as the ADNP syndrome (ADNPS), by Krajewska-Walasek et al. (2016) and wish to add to the literature another report of a patient with HVDAS/ADNPS who had novel features. Unlike the other reported patients with HVDAS/ADNPS, in whom behavioral manifestations were noted (Krajewska-Walasek et al., 2016), our patient does not appear to have autism or autism spectrum disorder. He has been described by his parents and observed by medical professionals, including a developmental pediatrician, to be very social, cooperative, and affectionate. Additionally, he also has several features that have not been previously described in patients with HVDAS/ADNPS.

The patient is a 12 year old boy who presented with a history of developmental delay. He had poor head control at 3 months and did not sit independently until 11 months of age. He walked at 24 months, reached for objects around 14 months and had a poor pincer grasp at 21 months. He spoke his first words after 2 years of age. He had fewer than 200 words at 3 years and continues to have limited verbal skills despite speech therapy. He was toilet trained at age 12. Behaviorally, he is said to have a mild disposition with only occasional tantrums. He is also reported to have attention deficit without hyperactivity. He is described as very social, cooperative, and affectionate. He has no repetitive or ritualistic behavioral problems except for a tendency to chew on hard objects, such as bottle caps and earphones. These did not appear to be an obsession, nor associated with anxiety. A formal autism evaluation was not done due to the lack of a clear clinical indication.

His past medical history is remarkable for hypothyroidism and hypertension (190/100 mmHg) diagnosed at the age of 4, for which he receives treatment. He had orchidopexy for retractable testicles at 18 months.

Review of systems is significant for left eye myopia and right eye hyperopia. He also has intermittent constipation and diarrhea with abdominal pain. He has never had seizures. His hearing is normal.

In terms of his growth parameters, he was delivered at 38 weeks with a birthweight of 2.78 kg, just above the 25th centile (head circumference and length were not documented). By age 2, his height, weight, and head circumference were all at the 50th centile. Over the years, his weight has progressed to above the 50th centile by age 3, above the 90th centile by age 7 and above the 98th centile by age 12 (62.5 kg). His head circumference has also progressed from the 50th centile to 75th centile by age 3, to above 98th centile by age 12 (56.7 cm). His height has remained near the 50th centile.

His craniofacial features (Figure 1) include a broad forehead, bushy eyebrows with apparently widely-spaced eyes, wide palpebral fissures, long eyelashes, everted lower eyelids, and left eye strabismus. He also has infraorbital creases and depressed nasal bridge with a short nose. The philtrum is not well formed, the upper lip is thin, and the lower lip is slightly protruding. The facial profile is flat. The ears are prominent with fleshy upturned lobules. He also has a low posterior hairline. Other features on physical exam include a highly arched palate, a midline crease of the uvula, a normal-sized phallus but hypoplastic scrotum and retractable testicles. The anus is normally positioned. Examination of the chest, abdomen, back, and extremities as well as the skin is unremarkable. He is hypotonic. His range of motion of the joints is within normal limits.

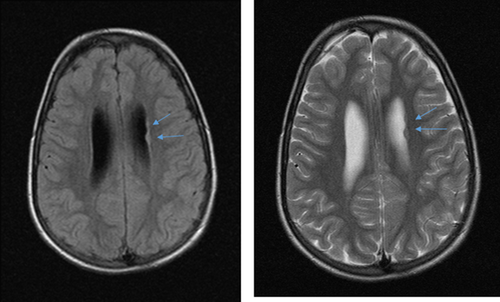

He has been investigated for a chromosomal etiology and has a normal karyotype and microarray. Genetic testing for Kabuki, Sotos, and Fragile X syndromes was normal. Brain MRI showed mild ventriculomegaly with no hydrocephaly. Two areas of gray matter heterotopia were noted on the left ventricular wall (Figure 2). His bone age at 22 months was 36 months, equivalent to +3.5 SD above the mean. Cardiac and renal imaging was normal. Exome sequencing revealed a de novo mutation, c.2491-2494delTTAA in ADNP, which was previously described to be pathogenic (Helsmoortel et al., 2014).

Taken together, our patient has many of the typical findings present in individuals with HVDAS/ADNPS as summarized by Krajewska-Walasek et al. (2016); but he also manifests some unique features, notably the lack of autistic behaviors which were noted in all previous patients. He has not had a formal autism assessment as there has been no clinical indication for it. Features not reported in previous patients also include advanced bone age, periventricular heterotopia (Figure 2) and late onset progressive macrocephaly. Also of interest, the prominent forehead with high anterior hairline, one of the most consistent features of this condition, has become less pronounced with age in our patient (Figure 1) while obesity and macrocephaly have evolved over the same time period.

The ADNP gene is highly conserved across species (Mandel, Rechavi, Gozes, 2007). However, even identical mutations in the same gene may not yield the same phenotype, illustrating the clinical heterogeneity of the condition. Our patient also serves to broaden the phenotypic spectrum of HVDAS/ADNPS. This report also provides a proof of principle that the availability of exome sequencing leads to the identification of previously unrecognized syndromes, particularly in patients who present with atypical and/or novel features.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the parents’ permission to publish this case and their supply of photos of their son at 3 1/2 months and 18 months of age.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.