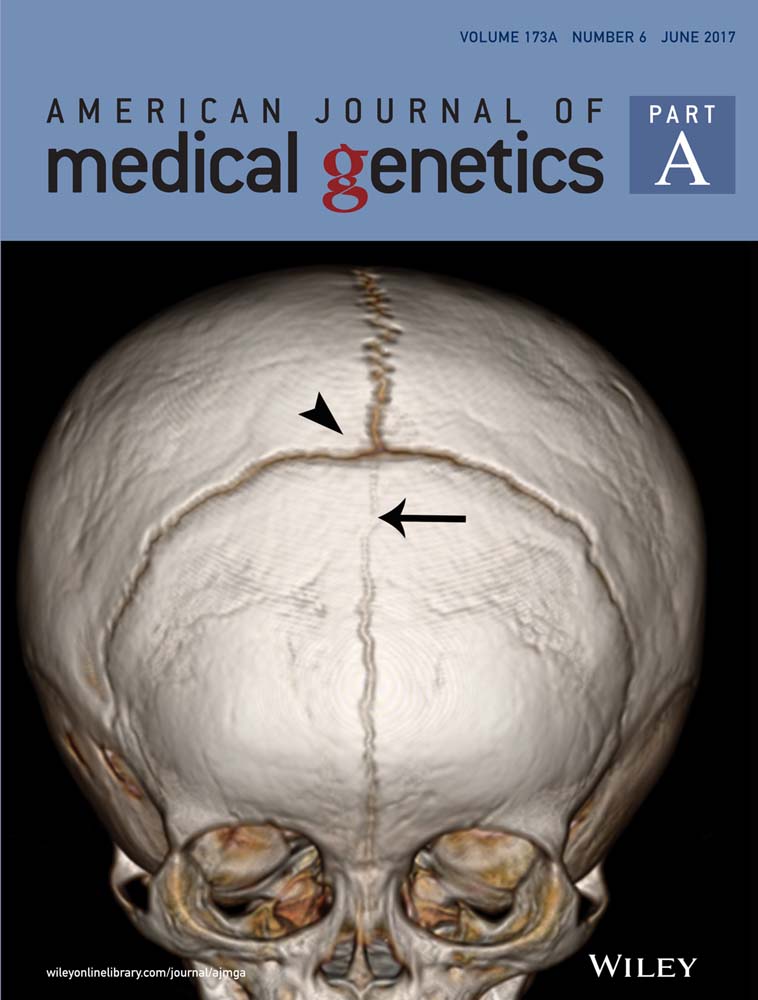

Variable clinical course of identical twin neonates with Alström syndrome presenting coincidentally with dilated cardiomyopathy

Abstract

Alström Syndrome (AS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ALMS1 gene. We report monozygotic twin infants who presented concurrently with symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF) due to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Following their initial presentation, one twin improved both echocardiographically and functionally while the other twin showed a progressive decline in ventricular function and worsening CHF symptoms requiring multiple hospitalizations and augmentation of heart failure therapy. Concordant findings of nystagmus, vision loss, and developmental delay were noted in both twins. Additional discordant findings included obesity and signs of insulin resistance in one twin. Genetic testing on one sibling confirmed AS. These twins underscore the importance of considering AS in any child presenting with DCM, particularly in infancy, and highlights that, even in monozygotic twins, the clinical course of AS is variable with regard to both the cardiac and non-cardiac manifestations of the disease.

1 INTRODUCTION

Alström Syndrome (AS) (OMIM #203800) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ALMS1 gene. It is characterized by a wide range of clinical features that emerge as the affected individual ages. Major features include cone-rode dystrophy causing nystagmus, photophobia and childhood blindness, obesity, insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes, progressive sensorineural hearing loss, short stature, developmental delay, pulmonary disease, liver disease, and renal disease. More that 60% develop congestive heart failure (CHF) secondary to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), often presenting in infancy, or restrictive cardiomyopathy that develops later in adulthood. The infantile onset DCM can be transient and improve with time. However, a small percentage may have spontaneous recurrence at a later age. Clinical features, age of onset and severity may vary even within families (Mahamid et al., 2013). The etiology of the intra-familial variability may be secondary to germline modifier genes or due to stochastic events such as environmental factors or somatic genetic changes. The intra-familial variability in the AS phenotype has yet to be described in monozygotic twins. Herein we report monozygotic twin neonates with AS presenting concurrently with DCM/CHF, but then following a highly variable disease course with regard to the cardiac and some non-cardiac manifestations of the disease.

2 CLINICAL REPORTS

In this report we describe monochorionic, diamniotic twin girls who were born full term to a healthy 42 year old mother and healthy 44 year old father. Parents are of Peruvian heritage who deny consanguinity. Family history was significant for a cousin on the paternal side who had a history of DCM at the age of 7 months that spontaneously resolved.

3 TWIN 1

Twin 1 presented at 5 weeks of age with cardiogenic shock and was found to have DCM with moderate left ventricular (LV) dysfunction (ejection fraction 35%, Ross Class IV). The myocardium also appeared hyper-trabeculated but did not meet criteria for non-compaction. The patient was initially supported with mechanical ventilation, dopamine, milrinone, and diuresis, and received one dose of intravenous immunoglobulin for presumed myocarditis. Cardiac catheterization demonstrated normal diastolic filling pressures and low pulmonary vascular resistance. Endomyocardial biopsy showed myocyte hypertrophy and patchy interstitial fibrosis consistent with DCM. A comprehensive cardiomyopathy panel did not identify any disease-causing mutations and screening for evidence of metabolic and mitochondrial diseases was negative. The patient eventually improved, transitioned to oral anti-congestive therapy (furosemide, captopril, spironolactone, and aspirin), and was discharged from the hospital after 12 days (Ross Class II).

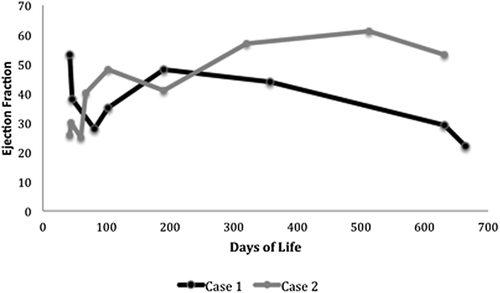

Over the next 21 months, despite optimizing medical therapy with the addition of carvedilol, digoxin, and increased diuretics, the patient demonstrated worsening CHF with the most recent ejection fraction of 24%. (Figure 1) She has had five hospitalizations for CHF exacerbations and is symptomatic with minimal exertion (Ross Class III).

Around the age of 7 months, the patient was noted to have horizontal nystagmus and photophobia. Subsequent ophthalmologic exam showed visual acuity of 20/540. These findings were consistent with cone-rod dystrophy though electroretinography (ERG) was deferred. Tympanometry and distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOE) testing revealed normal hearing. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was normal.

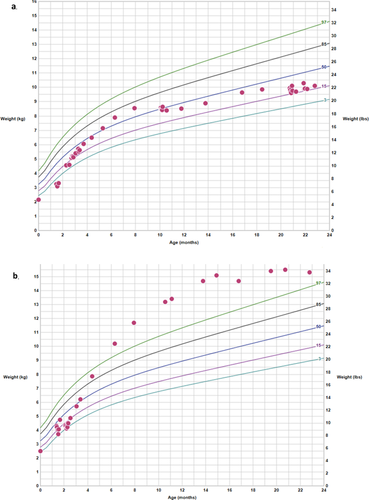

The patient did not roll over or sit independently until the age of 12 months but walked by 15 months. By 22 months of age she had significant speech delay. She is walking independently but still has poor balance. Behaviorally, she demonstrates several features concerning for autism spectrum disorder, including poor eye contact, lack of a social smile, and disinterest in social interaction. Her weight since 11 months of age has remained between the 15th and 40th centiles, and her length between the 15th and 50th centiles (Figure 2a).

Based on a clinical phenotype suggestive of AS, sequencing of ALMS1 was performed which showed pathogenic compound heterozygous mutations, molecularly confirming AS. The first variant (c.2816T > A; p.Leu939*) was predicted to result in premature protein termination, and the second variant (c.10837_10838delCA; p.Gln3613Alafs*2) was predicted to result in translational frameshift and premature protein termination.

4 TWIN 2

Twin 2 presented concurrently at 5 weeks of age with mild respiratory distress. An echocardiogram showed severely decreased LV function with an ejection fraction of 26%, confirming the diagnosis of DCM (Ross Class IV). Similar to her sister, a comprehensive cardiomyopathy panel was negative as was screening for evidence of metabolic and mitochondrial diseases. Despite severe LV dysfunction, the patient did not require intubation or inotropes and was eventually discharged from the hospital after 7 days on oral anti-congestive therapy (furosemide, captopril, and spironolactone) with minimal symptoms (Ross Class II).

By 22 months of age her ventricular function improved, showing only mild LV dysfunction (ejection fraction 53%). She has had only one hospitalization for fluid overload and remains asymptomatic on oral anti-congestive therapy (Ross Class I).

Similarly to her sister, the patient was noted to have horizontal nystagmus and photophobia. Subsequent ophthalmologic exam showed severe visual impairment. These findings were consistent with cone-rod dystrophy though ERG was deferred. Tympanometry and DPOE testing revealed normal hearing. MRI of the brain was normal. Despite her heart failure, the patient developed severe obesity with weight and BMI > 99th centile for age (with a maximum weight z-score of +3.5) despite caloric restriction (Figure 2b). Length after 6 months of age remained between the 50th and 90th centiles. Given her obesity, she was evaluated by endocrinology and fasting glucose and insulin levels were reported as normal. They did note darkening of the skin around the neck with no change in texture, which may reflect an early sign of insulin resistance.

She is also globally delayed. She did not sit independently until 12 months of age, and is unable to walk without support, but does cruise and pull to stand. She has significant speech delay. Behaviorally, she demonstrates several features concerning for autism spectrum disorder, with poor eye contact, lack of a social smile and disinterest in social interaction.

Given her clinical findings and the confirmation of pathogenic mutations in ALMS1 in her monozygotic twin, the diagnosis of AS was made clinically; targeted ALMS1 molecular testing was deferred by the family.

5 DISCUSSION

Roughly half of children with AS will develop DCM (Michaud et al., 1996). Many will show resolution of DCM in childhood that may or may not recur in adolescence (Marshall, Beck, Maffei, & Naggert, 2007). Intra-familial heterogeneity of the clinical course of DCM in AS patients has been reported (Hoffman, Jacobson, Young, Marshall, & Kaplan, 2005). Moreover, the extra-cardiac manifestations of AS are also variable and may include nystagmus, cone-rod dystrophy leading to blindness, sensorineural hearing loss, acanthosis nigricans, type 2 diabetes, obesity, renal or hepatic impairment, and developmental delay, which may not all occur or may present at different times (Michaud et al., 1996). In the present patient, DCM/CHF was the first presenting symptom, nystagmus appearing in both siblings 6 months thereafter, developmental delay was recognized around the age of 1 year, and visual impairment around the age of 18 months. However, the clinical trajectory of these patients diverged early despite monozygosity and similar initial presentation, particularly with regard to their cardiac disease and obesity. Of note, the twin with CHF did not develop obesity, possibly as a result of the high metabolic expenditure often seen in children with heart failure.

This report has several important learning points. Firstly, AS should be considered in infants presenting with DCM/CHF even if the DCM improves. Secondly, even in monozygotic twins, the clinical course of AS may vary with regard to cardiac disease manifestations and obesity. Such variability suggests that epigenetic factors may play a role in disease presentation, though this is poorly understood. Lastly, at this point in time not all laboratories include ALMS1 in their gene panels for DCM. In select cases where clinical symptoms are consistent with AS, genetic testing for ALMS1 should be considered.

The rarity of its incidence and the heterogeneity of its clinical manifestations, even in monozygotic twins, makes the diagnosis of AS difficult. Early consideration of ALMS1 testing in any patient with DCM and any of the extracardiac manifestations of AS, particularly in infants with a family history of cardiomyopathy will facilitate earlier diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are no funding sources to acknowledge.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.