Molecularly proven mosaicism in phenotypically normal parent of a girl with Freeman–Sheldon Syndrome caused by a pathogenic MYH3 mutation

Abstract

We report a case of a female child who has classical Freeman–Sheldon syndrome (FSS) associated with a previously reported recurrent pathogenic heterozygous missense mutation, c.2015G > A, p. (Arg672His), in MYH3 where the phenotypically normal mother is a molecularly confirmed mosaic. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in the medical literature of molecularly confirmed parental mosaicism for a MYH3 mutation causing FSS. Since proven somatic mosaicism after having an affected child is consistent with gonadal mosaicism, a significantly increased recurrence risk is advised. Parental testing is thus essential for accurate risk assessment for future pregnancies and the use of new technologies with next generation sequencing (NGS) may improve the detection rate of mosaicism. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Freeman–Sheldon syndrome (FSS; OMIM #193700) was first described in 1938 as “cranio-carpo-tarsal dystrophy” by Freeman and Sheldon [1938]. FSS is a rare, multiple congenital contracture syndrome which is one of the distal arthrogryposes series (type 2A). It is characterized by contractures of the distal joints of the hands and feet, usually camptodactyly and clubfoot, respectively, and is relatively well-known, because affected children have a striking appearance: it was historically called “whistling-face syndrome” because of involvement of the facial muscles resulting in a very small oral orifice, often only a few millimeters in diameter, at birth.

It was first reported in 2006 that heterozygous mutations in MYH3 cause FSS [Toydemir et al., 2006]. In a 2006 study, 26 out of 28 cases (93%) of clinically diagnosed patients with FSS were found to have mutations in the coding region of the MYH3 gene [Toydemir et al., 2006]. These cases are usually associated with a de novo presentation, and therefore recurrence risk for future pregnancies is considered low. Although considered to be an autosomal dominant condition, there have been a small number of reports suggesting an alternate form of inheritance, following more than one affected child being born to unaffected parents [Alves and Azevedo, 1977; Kousseff et al., 1982; Fitzsimmons et al., 1984; Sanchez and Kaminker, 1986; Wang and Lin, 1987; Dallapiccola et al., 1989; Bekir et al., 1994; Carakushansky et al., 2001]. These case reports pre-date the availability of MYH3 gene molecular testing.

We present the case of a girl with FSS diagnosed clinically in the neonatal period who is heterozygous for the recurrent pathogenic missense mutation c.2015G > A, p. (Arg672His) in MYH3, causing FSS. On parental testing, her phenotypically normal mother was found to be mosaic for the MYH3 mutation. The mother is therefore considered to be at significant future risk (up to 50%) of having another child with FSS.

CLINICAL REPORT

A new born baby, who was an inpatient on the neonatal special care unit, was referred to our team because of dysmorphic features and distal arthrogryposis. She was the first child of unrelated healthy white parents. The father had a well 11-year-old son from a previous relationship. There was no family history of note. Her parents both had a normal examination.

During pregnancy, the 35-year-old mother had experienced pregnancy-induced hypertension. There was no exposure to teratogenic agents and the 12 week ultrasound scan was normal. The 20 week ultrasound scan detected a small stomach, as well as hands held in a clenched position. At this point, there were initial concerns about distal arthrogryposis. Subsequent ultrasound scanning detected polyhydramnios but this resolved by 34 weeks. The baby's hands persisted in fixed flexion.

After induction of labor, the baby girl was born at 41+5 weeks gestation by vaginal delivery with forceps assistance. Her birth weight was 3,830 g (between 50 and 75th centiles) and she had a head circumference of 35.8 cm (near 91st centile). No resuscitation was required and her Apgar scores were 6 at 1 min and 9 at 5 min. She was able to self-ventilate from birth. There was difficulty establishing feeds and she was commenced on nasogastric tube feeding with expressed breast milk.

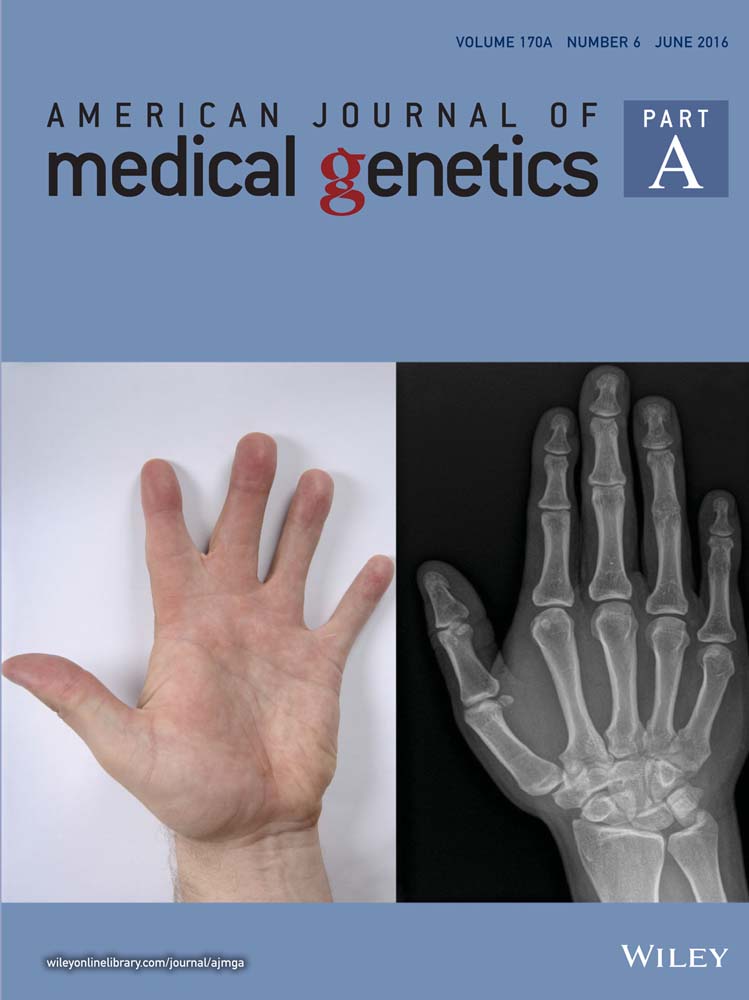

On the 6th day, she was noted to have deep set eyes with short and downslanting palpebral fissures. There was a degree of telecanthus. She had a rather broad nasal root with a short nose and upturned nares with hypoplastic alae. She had a long philtrum. Her mouth was small and reminiscent of a whistling appearance. She had a small receding chin with unusual cutaneous dimpling. Her ears showed over-folded helices which were similar to her mother's left ear. Her palate was normal. The hairline was relatively low posteriorly. Her hands revealed flexion contractures of the fingers and thumbs with the fingers held in ulnar deviation. There was some overlapping between the index and middle fingers on the right hand. Unusual deep palmar creases were noted bilaterally. On the right side, her fingers and thumbs did partially extend actively and passively whereas on the left hand, the fingers and thumbs were held in fixed flexion with difficulty extending passively. Her feet did not have frank talipes equinovarus but were held in a varus position and overlapping toes were noted, which mainly involved the hallux and second and third toes bilaterally. There were deep unusual vertical grooves bilaterally on the plantar surfaces of the feet. There were no other larger joint contractures, the spine appeared normal and the rest of the external examination was unremarkable (see Fig. 1A and B).

The baby had undergone an echocardiogram which was essentially normal, other than showing a patent foramen ovale and a patent ductus arteriosus. These had both closed spontaneously by 6 months of age. An upper GI contrast study was unremarkable and Comparative Genomic Hybridization analysis showed no significant copy number variants.

The baby was discharged home on day 12 of life. She made good progress in feeding and weight gain and was able to combine nasogastric feeding with oral feeding, using expressed breast milk in a bottle with an orthodontic teat. However, to maintain her calorie intake and growth, a gastrostomy tube was fitted at 7 months old. Due to the microstomia and laryngomalacia, the infant could not be intubated and a laryngeal mask airway was used during the anaesthetic. There were no additional complications during the procedure.

At 8 months of age, her weight was 7.73 kg and her height was 69.2 cm (both 50th centile). In the first year of life, six teeth erupted. Her parents managed well with her dental hygiene, despite continuing difficulties with fully opening the infant's mouth. The infant had continuous drooling from her mouth, which meant she needed many changes of clothes throughout the day.

On audiology assessment, the infant had continuing bilateral middle ear effusions and, as a result, was found to have reduced hearing at the low frequencies. She had multiple recurrent respiratory infections in the first year of life. She also experienced disordered breathing during sleep with snoring episodes, which were thought likely due to adenoidal hypertrophy. A home oximetry study revealed evidence of desaturations and sleep apnea. She was reviewed by the pediatric ear, nose, and throat (ENT) team and she may undergo grommet insertion and adenoidectomy in the future. The latter procedure may be done via nasal endoscopy, because of her limited mouth opening. She will also undergo plastic surgery for hand reconstruction at a future date. The child had regular ophthalmology assessments and at a year of age, had mild hypermetropia and a right ptosis, with patching in the left eye commenced to prevent amblyopia. Surgical correction of the ptosis may be required. Strabismus was not noted.

She was reviewed by our team at approximately a year of age (see Fig. 1C). At this point, she was making good developmental progress and was able to sit without support and bottom shuffle, as well speak a few words. She had been able to increase her oral intake and consequently required less feeding via her gastrostomy tube. The orthopedic team had recommended that she wear a dynamic elastomeric fabric orthosis suit and her mild scoliosis was remaining stable.

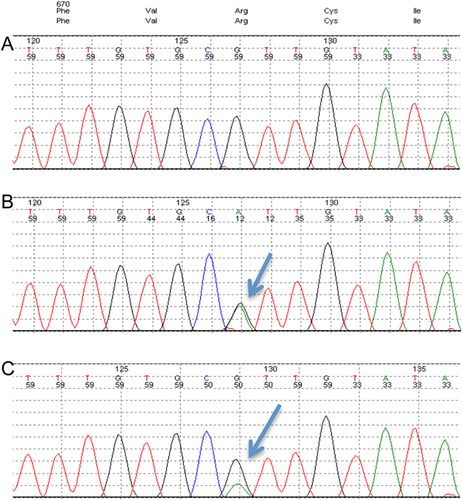

Based on the initial findings as a neonate, which strongly suggested a clinical diagnosis of FSS, DNA extracted from blood was sequenced on the local diagnostic clinical exome pipeline and analyzed for a distal arthrogyposis panel of genes including MYH3 targeting FSS and the additional genes TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2, MYBPC1, MYH8, and FBN2. The genetic testing revealed a known pathogenic heterozygous missense mutation in exon 18 of the MYH3 gene, (c.2015G > A), predicted to cause an arginine to histidine substitution in codon 672, p. (Arg672His), (Fig. 2B, compare with reference sequence in 2A).

To determine the inheritance of the mutation, both parents were offered testing for the familial mutation. The child's father did not carry the MYH3 mutation whereas her mother was found to be somatic mosaic on white blood cell analysis, with approximately one quarter (25%) of the cells tested being positive for the MYH3 mutation (Fig. 2C). Thorough examination of her mother established that she did not display any clinical features of FSS.

The couple were counselled that the recurrence risk in a future pregnancy would now be high (up to 50%). Reproductive options such as prenatal testing and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) were discussed with the family. They are currently in the midst of planning their next pregnancy and considering prenatal testing rather than PGD in view of maternal age.

MOLECULAR ANALYSES

Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) of the coding region (±5 bp) of the following genes (reference sequences) was performed using the Illumina TruSight One sequencing panel: MYH3 (NM_002470.3), TNNI2 (NM_003282.3), TNNT3 (NM_006757.3), TPM2 (NM_213674.1), MYBPC1 (NM_002465.3), MYH8 (NM_002472.2), FBN2 (NM_001999.3). Hundred percent of the target sequence within this panel was sequenced to a depth of 20-fold or more. This identified the recurrent c.2015G > A, p. (Arg672His) heterozygous missense change in the MYH3 gene. The presence of the c.2015G > A MYH3 variant was confirmed in the child by Sanger sequencing and tested in parental DNA samples extracted from blood. The PCR amplification was performed using standard procedures (primer sequences are available on request) and the sequencing products electrophoresed on an ABI3730 genetic analyzer. Sequence analysis was done using MutationSurveyor©. Mutations are named using HGVS nomenclature, where nucleotide one is the A of the ATG-translation initiation codon.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of molecularly confirmed mosaicism in an unaffected parent after the birth of a child with classic FSS associated with the recurrent pathogenic MYH3 mutation c.2015G > A, p. (Arg672His), where amino acid substitutions in this codon have been reported in up to 72% of FSS cases [Toydemir et al., 2006]. p. (Arg672His) is associated with intermediate severity in phenotype [Beck et al., 2014].

In most cases of FSS caused by the c.2015G > A, p. (Arg672His) mutation in MYH3, the condition occurs as a de novo sporadic event with autosomal dominant inheritance [Beck et al., 2014]. Mutations causing FSS have only been reported in MYH3 to date, except in one report of a Chinese family with distal arthrogryposis where the affected family members met classical strict criteria for FSS. MYH3 testing was negative and a missense novel variant was identified in TNNI2, encoding the fast skeletal form of troponin I, which was predicted to be pathogenic and segregated with the phenotype in the family. The mother of the proband in this family had facial contractures only and was found to exhibit somatic mosaicism for the TNNI2 variant [Li et al., 2013].

There have previously been case reports of clinically diagnosed FSS being attributed to other inheritance patterns, including autosomal recessive and X-linked transmission due to sibling recurrence with clinically unaffected parents [Alves and Azevedo, 1977; Kousseff et al., 1982; Fitzsimmons et al., 1984; Sanchez and Kaminker, 1986; Wang and Lin, 1987; Dallapiccola et al., 1989; Bekir et al., 1994; Carakushansky et al., 2001]. Stevenson et al. [2006] proposes two explanations for this. The first hypothesis is that some of the individuals may not meet diagnostic criteria for FSS, and therefore may have a separate diagnosis (possibly another form of distal arthrogryposis). The second hypothesis postulates that the other inheritance patterns proposed may in reality represent cases of parental germline mosaicism or non-penetrant somatic mosaicism. The findings in this case report support the second hypothesis in this family.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, our patient is the first reported case of a child with classical FSS, caused by a common MYH3 mutation, who has an unaffected mother with molecularly proven somatic mosaicism, who is also a likely gonadal mosaic. This case emphasizes the importance of parental genetic testing, when a clinically apparent de novo diagnosis is suspected in a child. It also illustrates the need to inform the families of the real possibility of parental mosaicism which can be associated with a significantly increased recurrence risk, and of the available reproductive options.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patient's family for their support and consent to this publication. We also thank the multidisciplinary teams at CUHNFT and Great Ormond Street Hospital who are involved in the care of this patient.