Muenke syndrome: An international multicenter natural history study

Abstract

Muenke syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by coronal suture craniosynostosis, hearing loss, developmental delay, carpal, and calcaneal fusions, and behavioral differences. Reduced penetrance and variable expressivity contribute to the wide spectrum of clinical findings. Muenke syndrome constitutes the most common syndromic form of craniosynostosis, with an incidence of 1 in 30,000 births and is defined by the presence of the p.Pro250Arg mutation in FGFR3. Participants were recruited from international craniofacial surgery and genetic clinics. Affected individuals, parents, and their siblings, if available, were enrolled in the study if they had a p.Pro250Arg mutation in FGFR3. One hundred and six patients from 71 families participated in this study. In 51 informative probands, 33 cases (64.7%) were inherited. Eighty-five percent of the participants had craniosynostosis (16 of 103 did not have craniosynostosis), with 47.5% having bilateral and 28.2% with unilateral synostosis. Females and males were similarly affected with bicoronal craniosynostosis, 50% versus 44.4% (P = 0.84), respectively. Clefting was rare (1.1%). Hearing loss was identified in 70.8%, developmental delay in 66.3%, intellectual disability in 35.6%, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 23.7%, and seizures in 20.2%. In patients with complete skeletal surveys (upper and lower extremity x-rays), 75% of individuals were found to have at least a single abnormal radiographical finding in addition to skull findings. This is the largest study of the natural history of Muenke syndrome, adding valuable clinical information to the care of these individuals including behavioral and cognitive impairment data, vision changes, and hearing loss. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

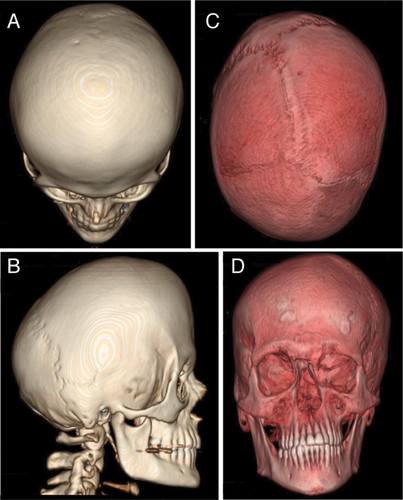

Craniosynostosis occurs in approximately 1 in 2,100 to 1 in 2,500 live births [Wilkie, 2000; Boulet et al., 2008], and is characterized by the premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures resulting in malformation of the skull (Figs. 1 and 2). Potential consequences of abnormal skull growth include increased intracranial pressure, problems with hearing and vision, impaired blood flow in the cerebrum, and developmental delay [Wilkie, 1997]. Craniosynostosis usually occurs as an isolated and sporadic anomaly in an otherwise healthy child; however, craniosynostosis is a component feature in over 150 described syndromes [Boulet et al., 2008]. The most common craniosynostosis syndromes include Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer, Saethre–Chotzen, and Muenke syndromes.

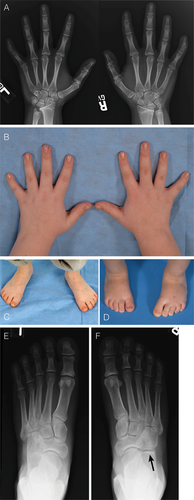

Muenke syndrome was first described in 1996 and is defined by the c.749 C>G mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene encoding a p.Pro250Arg substitution in the FGFR3 protein [Bellus et al., 1996; Muenke et al., 1997]. This mutation is one of the most common transversions in humans with an estimated mutation rate of 8 × 10−6 [Rannan-Eliya et al., 2004]. The classic presentation of Muenke syndrome includes uni- or bilateral coronal suture craniosynostosis (Figs. 1 and 1), broad toes, and carpal and calcaneal fusions (Fig. 3). However, the phenotype is quite variable and ranges from no detectable clinical manifestations to “isolated” craniosynostosis to more complex findings that overlap other classic craniosynostosis syndromes (e.g., Crouzon, Pfeiffer, or Saethre–Chotzen syndrome). Muenke syndrome constitutes the most common syndromic form of craniosynostosis, with an incidence of 1 in 30,000 births; of all patients with craniosynostosis, 8% have Muenke syndrome [Wilkie, 2000; Boulet et al., 2008]. For patients with craniosynostosis and an identified genetic cause, 24% have Muenke syndrome [Wilkie et al., 2010].

Multiple studies have contributed to the phenotypic characterization of Muenke syndrome. Recently, we reported behavioral differences in individuals with Muenke syndrome [Yarnell et al., 2015]. Furthermore, cognitive impairment, seizures, evidence of exclusive paternal origin associated with advanced paternal age [Rannan-Eliya et al., 2004], and need for reoperation because of increased intracranial pressure following surgery compared to other syndromic forms of craniosynostosis [Thomas et al., 2005] are associated with Muenke syndrome. There have also been suggestions that sexual dimorphism exists in the phenotype severity of Muenke syndrome [Gripp et al., 1998; Lajeunie et al., 1999]. To our knowledge, this report represents the largest collection of individuals with Muenke syndrome and, therefore our aims are to broaden the phenotype of Muenke syndrome and suggest new avenues for future research.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from craniofacial surgery and medical genetics clinics in North America, Europe, and Australia. Affected individuals, parents, and their siblings, if available, were enrolled in the study. The study was approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Institutional Review Board (IRB) under protocol 05-HG-0131 at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. Participants were eligible for participation in this study if they had the p.Pro250Arg mutation in the FGFR3 gene detected in a CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act of 1998) certified lab. Participating labs included both commercial labs and the Muenke Lab at the NIH. In cases where the mutation was confirmed to be de novo by negative genetic testing in both parents, siblings were considered unaffected without direct testing with the understanding that germline mosaicism would be the exception to this scenario. In families where one parent was identified to carry the FGFR3 p.Pro250Arg mutation, all children were tested to confirm carrier status. The phenotype data for individuals in this study was collected through clinical examination by at least one of the authors (P.K., H.C., T.S., C.A., J.M., T.R., M.M.).

DNA Analysis

Mutation status for all participants was determined from CLIA approved FGFR3 mutation results. For analysis done in the Muenke group, genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. FGFR3 sequence verification was performed using standard methods [Sanger et al., 1977]. Sequencing was performed with v3.1 BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in the ABI 3730xl Sequencer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sequence data were aligned to the published reference genomic sequence for FGFR3 (GenBank accession number NC_000004.12) using Sequencher 5.0.1 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI).

Statistical Analysis

Data manipulation were done with Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011, Version 14.4.5. Statistical analysis was conducted with R version 3.1.2 and with StatPlus:mac V5.

RESULTS

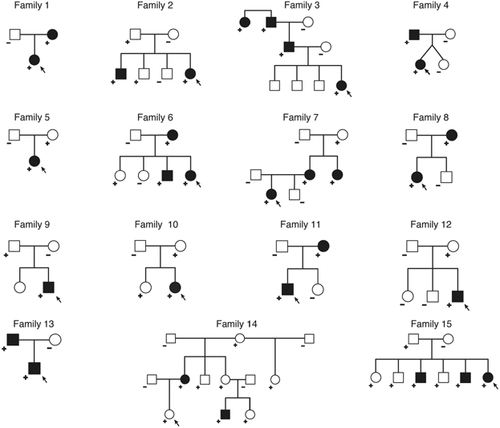

One hundred and six patients from 71 families participated in this study. Fifteen families had more than one individual with the p.Pro250Arg mutation in FGFR3 as shown in Figure 4. Table I lists all participants and their age, gender, and basic phenotype characteristics. Fifty seven percent (61/106) of our cohort was female. In 51 informative probands whose parents were tested for the p.Pro250Arg mutation, 33 cases (64.7%) were inherited.

| Patient | Age (years) | Gender | Type of craniosynostosis | Developmental delay | Hearing loss | Seizure history | Intellectual disabilitya | De novo | Paternal age at birth (y) | Maternal age at birth (y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5 | M | Bicoronal | − | − | − | Na | No | 33 | |

| 2 | 0.57 | M | Bicoronal | − | Na | 35 | 33 | |||

| 3 | 0.67 | F | Bicoronal | − | − | − | Na | 32 | ||

| 4 | 1 | M | Bicoronal/metopic | + | − | Na | Yes | |||

| 5 | 1 | F | Unicoronal | − | − | − | Na | No | ||

| 6 | 1 | M | Unicoronal | + | Na | Yes | 34 | 32 | ||

| 7 | 1 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | Na | No | 38 | 39 |

| 8 | 1 | F | Unicoronal | − | + | Na | Yes | 40 | 38 | |

| 9 | 1 | F | Bicoronal | − | + | − | Na | Yes | ||

| 10 | 2 | M | Bicoronal | + | − | − | Na | |||

| 11 | 2 | M | Unicoronal | + | + | − | Na | |||

| 12 | 2 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | Na | No | ||

| 13 | 2 | F | Bicoronal | + | − | − | Na | No | 44 | 44 |

| 14 | 2 | F | Unknown type | + | − | + | Na | 25 | 26 | |

| 15 | 2 | F | None | + | + | − | Na | No | 23 | |

| 16 | 2 | M | Unicoronal | − | − | − | Na | Yes | ||

| 17 | 2 | M | Bicoronal | + | − | − | Na | Yes | ||

| 18 | 3 | F | Unicoronal | − | − | − | Na | |||

| 19 | 3 | M | Unicoronal | + | − | Na | ||||

| 20 | 3 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | Na | No | 27 | 29 |

| 21 | 3 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | + | Na | Yes | 55 | 31 |

| 22 | 3 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | Na | Yes | 37 | 31 |

| 23 | 3 | M | Unicoronal | + | − | + | Na | Yes | 40 | 35 |

| 24 | 3 | M | Unicoronal | + | − | + | Na | Yes | 37 | 38 |

| 25 | 3 | M | Bicoronal | + | − | + | Na | No | 43 | 37 |

| 26 | 4 | F | Bicoronal | − | − | − | − | |||

| 27 | 4 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | No | 30 | 24 |

| 28 | 4 | F | Unicoronal | − | + | |||||

| 29 | 4 | M | Unknown type | + | + | − | + | No | 42 | 42 |

| 30 | 4 | F | Bicoronal | + | − | − | − | Yes | ||

| 31 | 5 | M | Bicoronal/sagittal | + | + | − | − | |||

| 32 | 5 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | No | ||

| 33 | 5 | F | Bicoronal | − | − | − | − | |||

| 34 | 5 | F | Bicoronal | − | + | − | − | No | ||

| 35 | 5 | F | Bicoronal | + | − | − | − | Yes | ||

| 36 | 6 | M | Unicoronal | − | + | − | − | Yes | 42 | 42 |

| 37 | 6 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | |||

| 38 | 7 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | |||

| 39 | 7 | F | Unicoronal | + | + | + | + | Yes | 44 | 26 |

| 40 | 7 | M | Unicoronal | + | + | + | 27 | 17 | ||

| 41 | 7 | M | Bicoronal | + | − | − | − | 35 | 34 | |

| 42 | 7 | M | Unicoronal | + | + | + | + | No | 18 | |

| 43 | 8 | M | Bicoronal | + | − | |||||

| 44 | 8 | F | − | 36 | 30 | |||||

| 45 | 8 | F | none | + | + | − | − | No | 23 | |

| 46 | 9 | F | Unicoronal | − | − | − | − | |||

| 47 | 9 | F | Unicoronal | − | + | − | 30 | 28 | ||

| 48 | 9 | M | Bicoronal | + | − | + | ||||

| 49 | 9 | M | none | − | − | − | − | No | 31 | 32 |

| 50 | 9 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | 54 | 34 | |

| 51 | 10 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | No | ||

| 52 | 10 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | Yes | 35 | 34 |

| 53 | 10 | F | Unicoronal | − | + | − | − | No | ||

| 54 | 10 | M | Sagittal | + | + | + | + | No | 30 | 31 |

| 55 | 10 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | 28 | 27 | |

| 56 | 11 | F | Unicoronal | + | + | − | + | |||

| 57 | 12 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | − | − | |||

| 58 | 12 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | |||||

| 59 | 12 | M | none | + | − | + | − | No | 33 | 34 |

| 60 | 12 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | − | − | 37 | 31 | |

| 61 | 12 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | No | ||||

| 62 | 13 | F | Unicoronal | − | + | − | − | |||

| 63 | 13 | F | Bicoronal | − | + | − | − | |||

| 64 | 13 | M | Unknown type | + | − | + | Yes | |||

| 65 | 14 | F | none | + | + | − | − | No | ||

| 66 | 14 | F | Bicoronal | − | + | − | − | |||

| 67 | 14 | M | Unicoronal | + | + | − | ||||

| 68 | 14 | F | Unicoronal | − | + | − | − | No | 31 | 26 |

| 69 | 14 | F | Unicoronal | + | − | − | + | 39 | 31 | |

| 70 | 15 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | + | + | |||

| 71 | 15 | F | Unicoronal | + | + | − | − | 32 | 30 | |

| 72 | 16 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | 35 | 37 | |

| 73 | 16 | F | none | − | − | − | No | 29 | 24 | |

| 74 | 16 | F | none | + | + | − | − | No | 38 | |

| 75 | 17 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | − | + | No | 22 | |

| 76 | 17 | M | Unknown type | + | + | + | + | |||

| 77 | 17 | M | Unicoronal | + | + | + | + | No | 28 | 29 |

| 78 | 17 | F | Bicoronal | − | − | − | − | 32 | 24 | |

| 79 | 18 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | + | + | |||

| 80 | 18 | M | Bicoronal | + | − | |||||

| 81 | 18 | F | Unicoronal | − | − | − | ||||

| 82 | 18 | F | Unknown type | + | − | − | + | 39 | 31 | |

| 83 | 19 | M | Bicoronal | + | + | − | − | |||

| 84 | 20 | M | none | + | − | − | No | 25 | 25 | |

| 85 | 20 | F | Bicoronal | − | + | − | − | Yes | 33 | 29 |

| 86 | 20 | F | Unicoronal | + | + | + | 34 | |||

| 87 | 21 | F | Unknown type | + | Yes | 34 | 31 | |||

| 88 | 24 | F | none | − | + | − | − | No | ||

| 89 | 25 | F | − | 41 | 31 | |||||

| 90 | 25 | F | none | + | + | − | − | No | 29 | |

| 91 | 27 | M | none | + | + | − | No | 27 | ||

| 92 | 28 | F | Bicoronal | − | + | − | − | No | ||

| 93 | 28 | F | none | + | + | + | + | 27 | 25 | |

| 94 | 31 | M | Unicoronal | + | − | − | ||||

| 95 | 31 | F | Bicoronal | + | + | + | − | No | 23 | |

| 96 | 33 | M | Bicoronal | − | − | − | − | |||

| 97 | 35 | M | Unicoronal | + | − | − | No | |||

| 98 | 37 | F | Bicoronal | − | − | − | − | 24 | 19 | |

| 99 | 37 | M | none | − | ||||||

| 100 | 40 | F | Bicoronal | − | + | + | − | 26 | 23 | |

| 101 | 41 | M | none | − | + | 31 | 26 | |||

| 102 | 43 | F | none | − | − | − | − | 30 | 25 | |

| 103 | 46 | F | Unicoronal | + | + | − | − | |||

| 104 | 54 | F | none | − | + | − | − | |||

| 105 | 56 | F | + | + | ||||||

| 106 | 67 | M | Bicoronal | − | + | − | − |

- a Greater than 4 years of age.

Table II lists the craniofacial findings in this study. Eighty-five percent of the participants had craniosynostosis, with 47.5% having bilateral and 28.2% with unilateral coronal synostosis. Females and males were similarly affected in bicoronal craniosynostosis, 50% versus 44.4% (P = 0.84), respectively. Clefting was rare, only 1 of 90 individuals evaluated for clefting had cleft lip (1.1%). Figure 2 shows three dimensional reconstruction of computerized tomography of unilateral and bilateral coronal craniosynostosis.

| Phenotype (N = 106) | Numbera (% of total) | Males number (% of total) | Females number (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Craniosynostosis | |||

| Craniosynostosis (all) | 87/103 (84.5) | 39/45 (86.7) | 48/58 (82.8) |

| Bicoronal synostosis | 49/103 (47.5) | 20/45 (44.4) | 29/58 (50) |

| Unicoronal synostosis | 29/103 (28.2) | 13/45 (28.9) | 16/58 (27.6) |

| Bilateral coronal and sagittal | 1/103 (1) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0 |

| Bilateral coronal and metopic | 1/103 (1) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0 |

| Sagittal | 1/88 (1) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0 |

| Craniosynostosis, NOS | 6/103 (5.8) | 3/45 (6.7) | 3/58 (5.2) |

| Not specified (“normal”) | 16/103 (15.5) | 6/45 (13.3) | 10/58 (17.2) |

| Skull shape | |||

| Normal | 7/86 (8.1) | 1/38 (2.6) | 6/48 (12.5) |

| Brachycephaly/Turribrachycephaly | 47/86 (54.7) | 21/38 (55.3) | 26/48 (54.2) |

| Plagiocephaly | 16/86 (18.6) | 7/38 (18.4) | 9/48 (18.8) |

| Macrocephaly | 19/86 (22.1) | 8/38 (21.1) | 11/48 (22.9) |

| Cloverleaf | 0/86 (0) | 0/38 (0) | 0/48 (0) |

| Surgery for craniosynostosis (of those with craniosynostosis) | 42/52 (80.8) | 17/23 (73.9) | 25/29 (86.2) |

| Facial findings | |||

| Hypertelorism | 39/82 (47.6) | 17/37 (45.9) | 22/45 (48.9) |

| Ptosis | 11/83 (13.3) | 6/38 (15.8) | 5/45 (11.1) |

| Proptosis | 5/81 (6.2) | 3/36 (8.3) | 2/45 (4.4) |

| Midface Hypoplasia | 37/56 (66.1) | 18/24 (75) | 19/32 (59.4) |

| High arched palate | 43/93 (46.2) | 16/39(41) | 27/54 (50) |

| Temporal bossing | 23/52 (44.2) | 9/22 (40.9) | 14/30 (46.7) |

| Cleft lip | 1/90 (1.1) | 0/38 (0) | 1/52 (1.9) |

- a The variability of examined individuals (denominator) reflects exam heterogeneity at different research sites.

Table III exhibits the neurologic findings identified in this cohort. Hearing loss was present in 70.8%. Ophthalmologic findings were common in our cohort as 57.6% of individuals had eye findings (see Table III). Eye findings correlated with the type of craniosynostosis, with unilateral coronal craniosynostosis being most affected as 94.7% had ophthalmologic diagnosis. None of the individuals without craniosynostosis were affected. The most common type of eye defect was strabismus, making up 44.9% of anomalies. Developmental delay was present in 66.3% (the majority attributed to speech delay) and intellectual disability in 35.6%. When the analysis was confined to age greater than 4 years, intellectual disability was present in 40.8%, ADHD was reported in 23.7%, and seizures occurred in 20.2%.

| Phenotype (N = 106) | Numberb (% of total) | Males number (% of total) | Females number (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ear findings | |||

| Hearing loss | 69/89 (70.8) | 23/35 (65.7) | 40/54 (74.1) |

| No hearing loss | 26/89 (29.2) | 12/35 (34.3) | 14/54 (25.9) |

| [Participants with hearing loss] | |||

| Unilateral hearing loss | 3/44 (6.8) | 1/15 (6.7) | 2/29 (6.9) |

| Bilateral hearing loss | 41/44 (93.2) | 14/15 (93.3) | 27/29 (93.1) |

| Conductive | 8/36 (22.2) | 2/12 (16.7) | 6/24 (25) |

| Sensorineural | 25/35 (71.4) | 10/12 (83.3) | 15/23 (65.2) |

| Conductive and sensorineurala | 3/35 (8.6) | 0/12 (0) | 3/23 (13) |

| [All participants] | |||

| Ear infections | 34/55 (61.1) | 14/24 (58.3) | 20/31 (64.5) |

| Tubes placed | 24/56 (42.9) | 11/25 (44) | 13/31 (41.9) |

| Developmental delay | 63/95 (66.3) | 32/38 (84.2) | 31/57 (54.4) |

| Motor | 21/95 (22.1) | 10/38(26.3) | 11/57 (19.3) |

| Speech | 58/95 (61.1) | 31/38 (81.6) | 27/57 (47.4) |

| Feeding | 9/95 (9.5) | 6/38 (15.8) | 3/57(5.3) |

| Other | 5/94 (5.3) | 2/37 (5.4) | 3/57 (5.3) |

| Intellectual disability (all ages) | 31/87 (35.6) | 16/35 (45.7) | 15/52 (28.8) |

| Intellectual disability (≥4 year) (31 people) | 29/71 (40.8) | 15/28 (53.6) | 14/43 (32.6) |

| ADHD diagnosis | 14/59 (23.7) | 7/26 (26.9) | 7/33 (21.2) |

| Seizure | 20/99 (20.2) | 11/42 (26.2) | 9/57 (15.8) |

| Hydrocephalus | 0/36 (0) | 0/16 (0) | 0/20 (0) |

| Chiari malformation | 2/51 (3.9) | 1/22 (4.5) | 1/29 (3.4) |

| Eye findings | |||

| Strabismus | 31/69 (44.9) | 16/30 (53.3) | 15/39 (38.5) |

| Amblyopia | 11/69 (15.9) | 5/30 (16.7) | 6/39 (15.4) |

| Astigmatism | 9/66 (13.6) | 5/29 (17.2) | 4/37 (10.8) |

| Nystagmus | 1/69 (1.5) | 1/30 (3.3) | 0/39 (0) |

| Other | 15/68 (22.1) | 7/29 (24.1) | 8/39 (20.5) |

| Eye findings (of those with complete ophthalmology data) | 38/66 (57.6) | 20/29 (69) | 18/37 (48.6) |

| Intracranial pressure | 11/41 (26.8) | 5/18 (27.8) | 6/23 (26.1) |

- a For cases where individuals had both kinds of hearing loss, the hearing loss has been “bilateral.”

- b The variability of examined individuals (denominator) reflects exam heterogeneity at different research sites.

Extremity x-ray findings are reviewed in Table IV. In patients with complete skeletal surveys (upper and lower extremity x-rays), 75% of individuals were found to have at least a single radiographical finding. Figure 3 shows typical hand and foot findings including capitate and hamate fusion, brachydactyly, and clinodactyly in the hand, and calcaneocubital fusion and broad toes in the foot.

| Allb (% of total) | Males number (% of total) | Females number (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical findings | |||

| Brachydactyly (hand and/or foot) | 11/48 (22.9) | 4/20 (20) | 7/28 (25) |

| Clinodactyly (hand and/or foot) | 10/47 (21.3) | 4/18 (22.2) | 6/29 (20.7) |

| Broad thumbs | 14/46 (30.4) | 8/28 (28.6) | 6/18 (33.3) |

| Broad toes | 39/81 (48.1) | 21/47 (44.7) | 18/34 (52.9) |

| Radiographic findingsa | 12/16 (75) | 4/8 (50) | 8/8 (100) |

| Carpal fusion | 2/27 (7.4) | 0/14 | 2/13 (15.4) |

| Calcaneal or tarsal fusion | 5/28 (17.9) | 2/14 (14.3) | 3/14 (21.4) |

| Thimble-like phalanges | 10/17 (58.8) | 3/8 (37.5) | 7/9 (77.8) |

| Cone-shaped epiphyses | 2/17 (11.8) | 0/8 | 2/9 (22.2) |

- a Participants with complete skeletal surveys.

- b The variability of examined individuals (denominator) reflects exam heterogeneity at different research sites.

DISCUSSION

In this large study of 106 individuals with Muenke syndrome, we are able to characterize the most common syndromic form of craniosynostosis. Our data shows that 64.7% of probands have inherited the p.Pro250Arg mutation, which has only been reported previously in a small study of eight patients demonstrating that 25% of the probands inherited the p.Pro250Arg mutation [Moloney et al., 1997]. We predict an even higher rate of inherited cases as parental testing was not done in our entire cohort. In five of 51 families in whom parents were tested, we found an asymptomatic parent who was a carrier, which was previously unknown to the carrier. Additionally, while doing cascade testing of parents and then siblings (if one parent was found to be positive), we found multiple FGFR3 p.Pro250Arg positive siblings without craniosynostosis, emphasizing the importance of testing family members without craniosynostosis. We found over 15% of our study group with p.Pro250Arg mutations to not have craniosynostosis; we would expect this number to rise given the ascertainment bias of most individuals presenting with craniosynostosis. Interestingly, even though craniosynostosis was not present in a significant minority of this study cohort, only 8.1% reported a normal skull shape (Table II).

Previous smaller studies have found bilateral coronal craniosynostosis more common in females. These studies include Gripp et al., who found all four of four males in their study to have unicoronal craniosynostosis; Cassileth et al. found six of six males with unilateral coronal craniosynostosis; Moloney et al. found five of six bicoronal craniosynostosis patients to be female; in Honnebier et al.'s study, 7 of seven unicoronal p.Pro250Arg participants were male; and, finally, Doherty et al. showed in a comprehensive literature review that 58% of females versus 37% of males had bicoronal craniosynostosis [Moloney et al., 1997; Gripp et al., 1998; Cassileth et al., 2001; Doherty et al., 2007; Honnebier et al., 2008]. In this study, 50% of females had bilateral coronal craniosynostosis versus 44.4% in males (P = 0.84, Fisher's Exact Test), and the penetrance of the craniosynostosis trait was also similar, 86.7% in males and 82.8% in females (P = 0.78, Fisher's Exact Test). This differs from smaller studies which have found that craniosynostosis penetrance was higher in females [Lajeunie et al., 1999; Doherty et al., 2007].

Based on a previous report, de novo mutations in Muenke syndrome are thought to originate in the paternal allele in older men; Rannan-Eliya et al. found in a study of de novo FGFR3 p.Pro250Arg mutations that all mutated alleles were paternal and the average paternal age was 34.7 years [Rannan-Eliya et al., 2004]. In our study, fathers of patients with de novo p.Pro250Arg mutations were on average 6 years older than fathers of patients with inherited mutations (39 years vs. 33 years; P = 0.02). While controlling for paternal age, maternal age was not predictive of mutation status (P = 0.45) as mothers of de novo patients and familial patients did not differ by age.

The term selfish spermatogonial selection has been described to explain the paternal age-effect and higher birth prevalence of diseases such as Apert syndrome (FGFR2), Costello syndrome (HRAS), and FGFR3-related diseases Muenke syndrome and achondroplasia [Goriely and Wilkie, 2012]. This concept suggests that de novo mutations in male germ cells confer a selective advantage to mutant spermatogonial stem cells, which in turn lead to clonal expansion [Goriely and Wilkie, 2012]. The FGFR3 receptor is part of the growth factor receptor-RAS signaling pathway, which is a regulator of stem cell homeostasis in the testis. We therefore hypothesized that dysregulation of this pathway could put individuals with Muenke syndrome at increased risk of cancer. There is however no epidemiologic data that links the p.Pro250Arg mutation in FGFR3 with cancer. In our study we are not aware of any of the 106 cases developing cancer; but, a longer longitudinal study will be needed in our cohort to more precisely answer this question. Given fibroblast growth factor receptors' association with cancer, the absence of cancer in the medical literature may be due to differential spatial and temporal activation of the FGFR3 mutation during development [Helsten et al., 2015].

The majority of participants (57.6%) in our study with eye exam data had ophthalmologic findings. Eye findings have been widely reported in craniosynostosis patients. In a review of 61 individuals with Apert syndrome, strabismus was identified in 63% of patients and amblyopia was found in 35% [Khong et al., 2006]. In a larger study of 141 patients with Crouzon, Pfeiffer, Apert, and Saethre–Chotzen syndromes, strabismus was present in 70% [Khan et al., 2003]. More specific to our cohort, Jadico et al. studied 21 patients with either Saethre–Chotzen or Muenke syndromes and found that those with an FGFR3 mutation had strabismus present in 55% and amblyopia in 18% [Jadico et al., 2006].

Sensorineural hearing loss is specific to Muenke syndrome when compared to other FGFR craniosynostosis syndromes [Doherty et al., 2007; Honnebier et al., 2008; Mansour et al., 2006]. The mouse model of Muenke syndrome shows a correlation with the alteration in the fate of supporting cells in the auditory sensory epithelium in the cochlear duct with low frequency sensorineural hearing loss [Mansour et al., 2006]. Specifically, aberrant organ of Corti development with excess pillar cells, too few Deiters' cells, and extra outer hair cells were found in the mouse model, with the most extreme abnormality at the apex of the cochlear duct which is responsible for low frequency sound transduction [Mansour et al., 2006]. Similar to previous studies [Agochukwu et al., 2014], our data are consistent with hearing loss being a significant trait in Muenke syndrome with over 70% of participants found to have some form of hearing loss. Additionally, we identified a significant association between hearing loss and ear infection history (P < 0.001; χ2 test), and a trend for more ear tubes placed in individuals with craniosynostosis.

In recent years, evidence for cognitive and behavioral differences in persons with Muenke syndrome has arisen [Flapper et al., 2009; Bannink et al., 2010, 2011; de Jong et al., 2012; Kapp-Simon et al., 2012; Maliepaard et al., 2014]. Our data combined with the below review of animal model data suggest that FGFR3 is involved in brain development. Even though FGFR3 was reported to have no definite role in cortical patterning [Grove and Fukuchi-Shimogori, 2003], FGFR3 has been shown to affect brain development by regulating proliferation and apoptosis of cortical progenitors [Inglis-Broadgate et al., 2005]. FGFR3 is expressed in the ventricular and subventricular zone throughout neurogenesis and in progenitor neuroepithelial cells from E9.5 and in the cortical ventricular and subventricular zones [Peters et al., 1993], and in FGFR3−/− mice, brain volume is decreased with cortical and hippocampal volumes reduced by 26.7% and 16.3%, respectively [Moldrich et al., 2011]. Thomson et al. [2009] found in mutant mice that constitutive activation of FGFR3 in the forebrain selectively promotes growth of caudolateral (occipitotemporal) cortex [Thomson et al., 2009]. Arnaud et al. [2002] found lower IQ scores in postoperative patients with Muenke syndrome compared to other patients with bicoronal synostoses, who were mutation negative [Arnaud et al., 2002]. In our data, the presence or absence of craniosynostosis in individuals with the p.Pro250Arg mutation did not alter the risk of developmental delay (P = 1), intellectual disability (P = 0.12) or sensorineural hearing loss (P = 0.33). A previous study found that behavioral differences were also not associated with craniosynostosis [Yarnell et al., 2015]. The sum of these observations point towards intrinsic brain differences and neurologic findings specific to the FGFR3 p.Pro250Arg mutations that are not associated with the presence of craniosynostosis.

Bilateral coronal synostosis is usually treated with fronto-orbital advancement before one year of age, which has been shown to have a better postoperative cognitive outcome and to prevent brachycephaly and intracranial hypertension [Arnaud et al., 2002]. Although Arnaud et al. showed better morphological outcomes, in particular the resolution of prominent temporal fossae bulging, and functional outcomes in patients with bilateral coronal synostosis without the FGFR3 p.Pro250Arg mutation when compared to Muenke syndrome patients with bilateral coronal synostosis, these results were not statistically significant [Arnaud et al., 2002]. Mean age of surgery for our cohort was 9 months (n = 38, SD = 4.5 months), which is within the standard of care. A larger percentage of females received surgery (86.2%) than males (73.9%), which was not a significant difference (P = 0.31, Fisher's exact test).

As always, consideration of the limitations of this study is appropriate. While inclusion of multiple sites allowed for the large sample size, it also resulted in study weaknesses due to the heterogeneous processes used to evaluate participants across the clinical settings. Various means were used to evaluate endpoints such as developmental delay and intellectual delay, including parent report, which provides the potential for variation. However, given the relative rareness of this disease, bringing all participants to a single center was not feasible.

In contrast, a notable strength of the study is that it is the largest natural history evaluation of persons confirmed to carry the FGFR3 p.Pro250Arg mutation to date and further expands the phenotypic spectrum of Muenke syndrome. This expansion includes higher numbers of persons who carry the associated mutation, but don't express the classic recognizable phenotype initially associated with Muenke syndrome. We encourage clinicians to pursue parental testing of newly identified patients, and if warranted further family testing (cascade genetic testing), which will further expand the phenotypic spectrum of Muenke syndrome. This study will be an excellent source of information on the most common hereditary craniosynostosis syndrome for both clinicians and affected families. This study characterizes the neurologic, craniofacial, and limb anomalies associated with Muenke syndrome and provides an updated foundation for further research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all study participants for providing information and/or biological samples for this study.