Brain magnetic resonance in the routine management of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (RTS) can prevent life-threatening events and neurological deficits

TO THE EDITOR

Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (RTS) is a rare syndrome with prevalence 1:125,000 births [Hennekam, 2006]. Distinctive characteristics are broad and sometimes laterally deviated thumbs and halluces, downslanting palpebral fissures, long eyelashes, high-arched eyebrows, prominent nose with columella below the alae nasi, malpositioned ears with abnormal helices, high palate, and hypoplastic maxilla. These patients present with moderate intellectual disability [Wiley et al., 2003].

Moreover, craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities have been commonly reported in the literature [Yamamoto et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2010; Wójcik et al., 2010; Parsley et al., 2011; Giussani et al., 2012; Marzuillo et al., 2013] including large foramen magnum, microcranium, spina bifida occulta, cervical hyperkyphosis, dens hypoplasia, cervical instability of C1–C2, cervical spondylolisthesis, and scoliosis. Symptoms that may be reported with these conditions are dysesthesias, paresthesias, anesthesias, recurrent sub-occipital headache, cervical pain, vertigo, tinnitus, aural fullness, and occasionally mild neurosensorial hearing loss. Ocular symptoms such as retro-orbital headache, diplopia, photopsia, blurred vision, and photophobia may be also present. In very severe cases in which compression of the spinal cord or medulla oblongata occurs, symptoms suggesting the involvement of motor or sensory pathways, as well as of lower cranial nerves may appear. However, if these symptoms also occur, they are extremely rare in individuals with RTS.

On the other hand, physical signs are represented by generalized hyperreflexia, spasticity, and Babinski reflex, mostly in the lower limbs; atrophy, weakness, fasciculations, and areflexia, mostly in the upper limbs; nystagmus, ataxia, and dysmetria. In 15–25% of the cases vocal cord paralysis, soft palate weakness, lingual atrophy, cricopharyngeal achalasia, facial hypoesthesia, and absent gag reflex suggest the involvement of the lower cranial nerves [Fernández et al., 2009]

Point mutations or deletions of the cAMP-response element binding protein-BP (CREBBP) (50–60% of the cases) or of the homologous gene E1A-binding protein (EP300) (5%) are involved in RTS [Hennekam, 2006].

We report on a girl with RTS delivered at term without any perinatal problems. Her birth weight and length were 2,500 g and 47 cm, respectively. Diagnosis was performed at birth on the basis of the presence of broad thumbs and toes, hypoplastic maxilla, malpositioned ears with dysplastic helices, and hypertelorism. No CREBBP and EP300 mutations were found. Right kidney agenesis was found at ultrasound abdomen screening whereas left kidney appeared normal. When she was 12 years old, because of short stature, she was referred to a pediatric endocrinology unit. Clinical examination showed the features of RTS syndrome. She had severe intellectual disability. Pubertal Tanner stage was PH2B3. Her stature was at −4.5 standard deviation score, and weight was between the 10th–25th centile. Bone age obtained by X-ray of the non-dominant hand and wrist, determined by TW2 method, was appropriate to chronological age. Biochemical and hormonal analysis were normal.

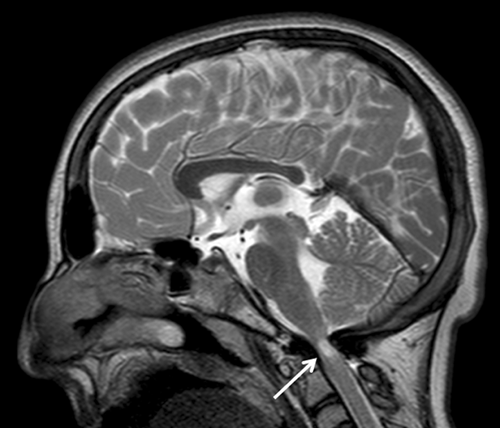

Because of intellectual disability, the patient's reporting of symptoms was impaired, so a screening brain magnetic resonance (MRI) in narcosis was performed to investigate the possible presence of craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities. The MRI showed severe stenosis of the foramen magnum with severe compression of medulla oblongata. Furthermore, an ischemic area was evident in this region (Fig. 1). This has eventually led to neurosurgical correction. It's important to underline that the patient did not show symptoms related to this condition probably because of the intellectual disability. Therefore, the possibility exists that, in this case, clinical signs of the medulla oblongata compression would have revealed later in life with an acute onset.

As previously described [Marzuillo et al., 2013], we cared for another RTS patient, completely asymptomatic, that at brain MRI showed Arnold Chiari malformation type 1 and at medullary MRI showed double syringomyelic cavity requiring surgical treatment. In literature, there are many cases of RTS patients with craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities (Table I). Only five RTS individuals reported in the literature had any manifestations that might be related to the neuroradiological findings, indicating that chances to develop such manifestations are small.

| Authors | Age of patient (years) | Sex | Craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giussani et al. | 11 | F | Arnold Chiari malformation with a cerebellar tonsils herniation of 11 mm, spinal syrinx from C2 to the conus medullaris and schisis of the anterior C1 arch and a posterior subluxation of the left occipital condyle determining a left tilting of the head on the neck | Yes (progressive dysphagia for liquids, episodes of apnea, loss of inferior limbs motor performances with the development of a rapid fatigability during the deambulation, diffuse inferior limbs hyperreflexia and scoliosis) |

| 13 | M | Cerebellar tonsils herniation of 6 mm, T5–T7 small syrinx and dysembriogenetic defect of segmentation of the posterior C2 and C3 arches with a fusion of the corresponding joints | Yes (impairment in the fine motricity and somatosensory evoked potential suggestive for a spinal involvement and scoliosis) | |

| Kim et al. | 4 | M | Arnold Chiari malformation | No |

| Marzuillo et al. | 14 | F | Arnold Chiari malformation and double spinal syringomyelic cavity | No |

| Parsley et al. | 13 | F (twin) | Arnold Chiari malformation, multiloculated syrinx and a medullary kink down to C2 with minimal tonsillar displacement | Yes (rapidly progressive scoliosis necessitating spinal fusion) |

| 13 | F (twin) | Arnold Chiari malformation with extensive and multiloculated spinal cord syrinx | No | |

| Yamamoto et al. | 13 | F | Myelopathy due to compression and stenosis at the craniovertebral junction, fusion of C2–C3 and hypoplasia of the atlas and occipitalization of the posterior arch of the atlas | Yes (gradually incapable of ambulating, recurrent seizures, increased tendon reflex of extremities and pathologic reflex including Babinski reflex) |

| 19 | F | Hypoplasia of the dens and hyper instability of C1–C2 with an expanded atlas-odontoid process interval and narrowing of the cervical spinal canal and atrophy of the cervico-medullary junction | Yes (upward tilt of the head and lower jaw protrusion without specific sign at neurologic examination) | |

| 3 | F | Stenosis and compression of the cervical cord, hypoplasia of the dens and occipitalization of the posterior arch of the atlas | No | |

| 23 | M | Os odontoideum with fibrous fusion of the anterior arch of the atlas | No | |

| 20 | M | Os odontoideum and a fusion of posterior element of C2–C3 | No | |

| Wojcik et al. | 2 | F | Arnold Chiari malformation with cerebellar tonsillar herniation 12 mm below the level of foramen magnum | No (after the diagnosis seizure-like episodes of spontaneous bouts of crying) |

| This case | 12 | F | Severe stenosis of the foramen magnum with important compression of medulla oblongata and ischemic area in this region | No |

Because of the intellectual disability, we suppose that RTS patients could be unable to describe symptoms and that the clinical examination sometimes could be doubtful for the intellectual disability-related lack of cooperation. Therefore, accordingly to two previous reports [Giussani et al., 2012; Marzuillo et al., 2013], we think that performing a screening brain MRI (and if needed medullary MRI) could be useful, also in absence of symptoms. This consideration is in contrast to the RTS medical guidelines [Wiley et al., 2003] stating that brain and medullary imaging studies should relate to the presenting symptoms and neurologic examination findings. However, we acknowledge that the indication we suggest is debatable and therefore may not be accepted by all RTS caregivers. In fact, patients could be symptomless throughout life and craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities are rarely life-threatening. On the other hand, there is also the possibility that to detect these malformations and to treat them when possible, it could improve the quality of life of these patients. In fact, RTS patients could have symptoms and discomfort related to craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities without being able to report them.

An important issue for a debate is when, in the patients' life, is it better to perform a brain MRI. Performing an MRI when an RTS patient is sufficiently cooperative to not require a narcosis could represent a reasonable solution. Nevertheless, if the intellectual disability is severe, it is likely that this kind of RTS patient will not be cooperative.

We think that the follow-up program should focus on the degree of the patients' intellectual disability. If the patients are able to describe symptoms and are cooperative at clinical examination, a wait-and-see approach could be reasonable. In this case, MRI should be performed only if neurologic symptoms are manifested.

If the intellectual disability of RTS patients is severe, with inability to report symptoms and to be cooperative at clinical examination, we propose to perform the brain MRI between the age of 5 and 6 and at pubertal age, because, in these periods, the accelerated growth velocity of the bones could worsen the craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities with increasing risk of developing neurological deficits or life-threatening conditions. Moreover, to strengthen the indication to perform an MRI, it could be useful to use pain scales specific for children with severe cognitive impairment [Massaro et al., 2013].

Finally, after the medical guidelines publication [Wiley et al., 2003] several patients with craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities were described, but besides these individual case reports, no stronger evidence or epidemiological studies are available in literature to definitely support our recommendation. Therefore, we suggest that a multicenter prevalence study of craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities in RTS and multidisciplinary expert meetings could be useful to establish the exact craniospinal and posterior fossa abnormalities prevalence and to achieve a consensus for the prevention and the management of these complications in RTS patients.