Cleft palate and ADULT phenotype in a patient with a novel TP63 mutation suggests lumping of EEC/LM/ADULT syndromes into a unique entity: ELA syndrome†

How to Cite this Article: Prontera P, Garelli E, Isidori I, Mencarelli A, Carando A, Silengo MC, Donti E. 2011. Cleft palate and ADULT phenotype in a patient with a novel TP63 mutation suggests lumping of EEC/LM/ADULT syndromes into a unique entity: ELA syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A 155: 2746–2749.

Abstract

Acro-dermato-ungual-lacrimal-tooth (ADULT) syndrome is a rare condition belonging to the group of ectodermal dysplasias caused by TP63 mutations. Its clinical phenotype is similar to ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft lip/palate (EEC) and limb-mammary syndrome (LMS), and differs from these disorders mainly by the absence of cleft lip and/or palate. We report on a 39-year-old patient who was found to be heterozygous for a c.401G > T (p.Gly134Val) de novo mutation of TP63. This patient had the ADULT phenotype associated with cleft palate. Our findings, rather than extend the clinical spectrum of ADULT syndrome, suggest that cleft palate can no longer be considered an element for differential diagnosis for ADULT, EEC, and LMS. Our data, added to other reports on overlapping phenotypes, support the combining of these three phenotypes into a unique entity that we propose to call “ELA syndrome,” which is an acronym of ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft lip and palate, limb-mammary, and ADULT syndromes. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Acro-dermato-ungual-lacrimal-tooth (ADULT) syndrome, ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft lip/palate (EEC) syndrome, limb-mammary syndrome (LMS), ankyloblepharon-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft palate (AEC) syndrome, and Rapp-Hodgkin syndrome (RHS), are a heterogeneous group of ectodermal dysplasias caused by TP63 mutations, showing autosomal dominant inheritance [Rinne et al., 2007]. These disorders share several clinical features, mainly arising from the defective development of epithelial (skin, hair, teeth, nail, apocrine glands including the mammary) and mesenchymal (palate and limbs) structures.

In particular, ADULT syndrome was described for the first time 17 years ago [Propping and Zerres, 1993], and, since then, about 20 cases have been reported [Propping et al., 2000; Amiel et al., 2001; Van Bokhoven et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2004; Slavotinek et al., 2005; Reisler et al., 2006; Rinne et al., 2006a; Kier-Swiatecka et al., 2007; Van Zelst-Stams and Van Steensel, 2009; Wang et al., 2009; Avitan-Hersh et al., 2010]. The condition is characterized by a variable association of the following features: Split-hand-foot-malformations (SHFMs), syndactyly, hypodontia, and/or early loss of permanent teeth, nail dysplasia, premature scalp hair loss, lacrymal duct obstruction, breast abnormalities, and excessive freckling. To the best of our knowledge, cleft lip and/or palate has never been reported in ADULT syndrome, and it is for this reason that the lack of orofacial clefting, rather than freckling (a specific but variable feature), appears to be the main feature that distinguishes the ADULT and EEC/LM syndromes [Rinne et al., 2006b; Avitan-Hersh et al., 2010].

We here describe a patient with cleft palate and ADULT phenotype whose molecular study showed the presence of a novel TP63 mutation.

CLINICAL REPORT

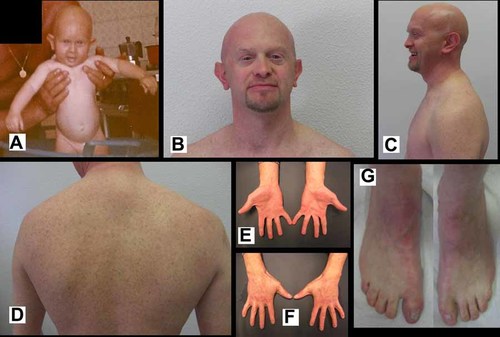

A 39-year-old male presented with an ectodermal dysplasia of unidentified etiology for diagnosis and genetic counseling of his clinical condition. The patient, born from healthy nonconsanguineous parents, at birth showed cutaneous syndactyly of fingers and toes, absent nipples, and cleft palate, but no ankyloblepharon, scalp defect, or freckling (Fig. 1A). Mild eczema of the scalp and bilateral conductive deafness appeared during the first years of life. At the time of our clinical examination his height was 172 cm (∼50th centile), weight 58.7 kg (∼50th centile), and OFC 56.5 cm (∼75th centile). His features included alopecia with fine hair, sparse eyebrows, absent eyelashes, lacrymal duct atresia, protruding ears with underdeveloped helices, malar flattening, primary hypodontia, early loss of permanent teeth, dry skin, dystrophic nails, cutaneous syndactyly of fingers (most marked between the third and fourth) and toes, clinodactyly of the fifth fingers, exfoliative dermatitis of the fingers and toes, absent nipples, café-au-lait spots, and extensive freckling (Fig. 1). His parents were examined and found to be normal for the findings described in the propositus.

A: The propositus at three months of age. Note the absence of freckling. B–D: The propositus at 39 years of age showing alopecia, sparse eyebrows, absent eyelashes, protruding ears, malar flattening, absent nipples, café-au-lait spots, and extensive freckling. E–G: Dystrophic nails, cutaneous syndactyly of fingers and toes, bilateral clinodactyly of the fifth finger, and exfoliative dermatitis of the fingers and toes.

Electron microscopy of skin showed flattening of the dermal papillae, thickening of the dermal connective tissue, elastic fiber degeneration, paucity and atrophy of glands, while a hair biopsy showed separation of hair corneal lamellae (data not shown).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood samples were taken from the patient and his parents following informed consent. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes by a DNA extraction kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). TP63 mutation analysis was undertaken by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing of the 16 exons and the intron–exon boundaries. The primers used for amplification have been previously described [Van Bokhoven et al., 2001]. The PCR products were purified using the QIA quick purification kit (QIAGEN GmbH, D-40724 Hilden, Germany). Sequencing was performed with the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). We used Chromosome Aneuploidies QF-PCR Kits (Experteam s.r.l, Venezia, Marghera, Italy) for determination of the STR patterns. Eleven STR loci were investigated (D21S1435, D21S1446, D21S11, D21S1411, D13S258, D13S631, D13S742, D13S303, X22, D18S858, and D18S390). The PCR products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis on CEQ™8000 Genetic Analysis System (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA). The mutation description was referenced to GenBank entry NM_003722.4.

RESULTS

The TP63 gene molecular study showed a heterozygous c.401G>T (p.Gly134Val) variant in the propositus, but this was absent in his healthy parents and in 100 normal controls. The analysis of STR markers demonstrated that the propositus was biologically related to the parents (data not shown).

The mutation is neither reported by the single nucleotide polymorphism (dbSNP at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp) nor by the Ensemble databases (www.ensembl.org).

The mutation disrupted a cleavage site for HaeIII (New England Biolabs), which cuts the normal exon 4 amplicon into two fragments. This transversion converted the highly conserved amino acid Glycine residue (GGC) to Valine (GTC) (p.Gly134Val) (CLUSTAL W (1.81) alignment, not shown) and its functional effect, analyzed by two prediction tools (SIFT: sorting intolerant from tolerant; http://sift.jcvi.org/ and PolyPhen: polymorphism phenotyping; http://www.bork.embl-heidelberg.de/PolyPhen/data), was predicted to be deleterious (SIFT: affected protein function, score: 0.00; PolyPhen: probably damaging, PSIC score: 2.717), thus supporting its pathogenicity.

DISCUSSION

TP63-ectodermal dysplasias are a group of disorders sharing clinical features, genetic origin, and transmission. In particular, EEC syndrome is characterized by ectrodactyly and cleft lip and/or palate, LMS by ectrodactyly, cleft palate, mammary gland, and/or nipple hypoplasia, but no predominant ectodermal defects which, on the contrary, are usually associated with ectrodactyly and hypoplastic/absent nipples in ADULT patients [Rinne et al., 2006b; Rinne et al., 2007; Avitan-Hersh et al., 2010]. In this respect, cleft lip and/or palate is a critical clue for differential diagnosis. In the patient described here, the presence of cleft palate and extensive freckling, besides hair and skin defects, was misleading, since the former is described in 30% of patients with LMS and in 40% of patients with EEC, while the freckling is a specific, although it is a variable feature of ADULT syndrome. In the patient reported here, freckling was not evident in the first years of life, but it developed during middle childhood. If the patient was evaluated before the freckling developed, he could have been classified at first as having the LMS syndrome, but later as being affected by the ADULT syndrome.

There are examples of intermediate phenotype or ambiguous clinical assessments that blur the boundaries of the ADULT/EEC/LM syndromes in the literature [Slavotinek et al., 2005; Reisler et al., 2006; Rinne et al., 2006b; Kier-Swiatecka et al., 2007; Van Zelst-Stams and Van Steensel, 2009; Avitan-Hersh et al., 2010]. For this reason, some authors suggested combining these phenotypes into a unique entity, but they encountered a number of objections, the most important being that some clinical features (such as orofacial clefting and freckling) could still lead to the sub-classification of these conditions and that the genotype–phenotype correlations are solid [Van Bokhoven et al., 2001; Van Bokhoven and Brunner, 2002]. Other authors have debated this argument and suggested to use a classification system that includes both phenotypes and genotypes [Robin and Biesecker, 2001].

The ADULT syndrome can be attributed to mutations in exons 3, 4, 6, or 8, LMS to mutations in exons 4,13, or 14, while EEC to mutations in exons 5–8, 13, or 14, thus showing substantial overlap [Van Bokhoven et al., 2001; Barrow et al., 2002; Rinne et al., 2007; Avitan-Hersh et al., 2010]. Moreover, there are also case reports of interfamilial variability: p.Arg227Gln, p.Arg280Cys, and p.Arg243Trp mutations were reported in patients with either EEC or ADULT phenotypes [Celli et al., 1999; Barrow et al., 2002; Reisler et al., 2006; Kier-Swiatecka et al., 2007; Rinne et al., 2007; Avitan-Hersh et al., 2010]. In this respect, it is also interesting to note that the mutation in the patient reported here involves codon 134 (p.Gly134Val) and that a different missense mutation in the same codon (p.Gly134Asp) was reported by Slavotinek et al. [2005] and by Rinne et al. [2007] in patients, with the ADULT and LMS phenotypes, respectively. Similarly, the p.Arg204Gln and p.Arg227Gln mutations have been described in families with LM or EEC syndromes [Rinne et al., 2006b].

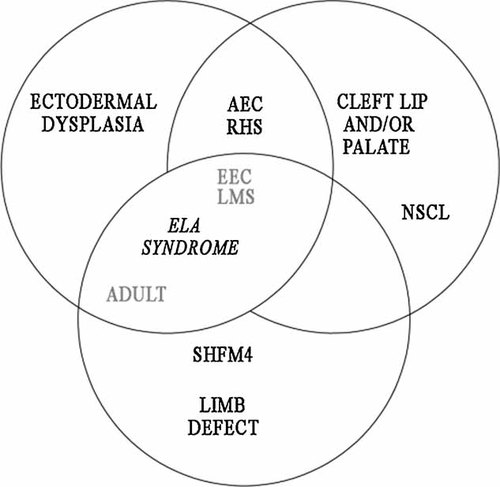

Currently, it is difficult to predict the phenotype on the basis of the genotype, and, even more importantly, it appears that there are insufficient clinical criteria to clearly distinguish these three syndromes from each other. Our observation of a patient with ADULT phenotype affected by cleft palate reopens the question, and on this bases, we suggest the combining of these conditions into a unique clinical entity, that we propose to call ELA syndrome, as an acronym of EEC/LM/ADULT syndromes (Fig. 2).

Schematic representation of the clinical overlap among the clinical entities belonging to the group of ectodermal dysplasias caused by TP63 gene mutations (adapted from [Rinne et al., 2007]). We propose to unite these three conditions (EEC/LMS/ADULT, in grey) into a unique entity: ELA syndrome. ADULT, acro-dermato-ungual-lacrimal-tooth; EEC, ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft lip/palate; LMS, limb-mammary syndrome; AEC, ankyloblepharon-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft palate; RH, Rapp-Hodgkin; SHFM4, split hand-foot malformation; NSCL, non-syndromic-cleft-lip/palate.

ELA syndrome could be used to classify patients with TP63-associated ectodermal dysplasias not showing AEC or RHS phenotypes that, on the other hand, represent another example of a continuous clinical spectrum [Bertola et al., 2004; Sahin et al., 2004; Rinne et al., 2006b; Prontera et al., 2008]. This new system could simplify the clinical classification of patients, without interfering with the prognostic evaluation, treatment, recurrence risk assessment, or laboratory work.