Somatic mosaicism for a CDKL5 mutation as an epileptic encephalopathy in males†

How to Cite this Article: Masliah-Plachon J, Auvin S, Nectoux J, Fichou Y, Chelly J, Bienvenu T. 2010. Somatic mosaicism for a CDKL5 mutation as an epileptic encephalopathy in males. Am J Med Genet Part A 152A:2112–2114.

To the Editor:

X-linked cyclin dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5, OMIM 300203) associated encephalopathy is a recently described X-linked disorder with a phenotype overlapping that of Rett syndrome (RTT, OMIM 312750) and X-linked infantile spasms (ISSX, OMIM 308350) [Bienvenu and Chelly, 2006]. To date, more than 50 patients with CDKL5 mutations have been described, but only five point mutations have been reported in boys, four missense mutations (p.L64P, p.R178P, p.T288I, p.C291Y), and one frameshift mutation (c.183delT) [Weaving et al., 2004; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2008; Elia et al., 2008; Fichou et al., 2009]. Strikingly, these patients with CDKL5 mutations show a similar clinical course: typically, seizures in the first months of life, severe hypotonia, poor eye contact, a three-step pattern epilepsy in most cases that includes infantile spasms, and some RTT-like features, such as secondary deceleration of head growth, severe motor impairment, sleep disturbances, hand apraxia, and hand stereotypies. Herein we report on a boy displaying a somatic mosaicism for a new splice mutation within the CDKL5 gene, providing evidence that somatic mosaicism could explain other cases of severe encephalopathy and early-onset epilepsy in males.

This patient is a boy, now aged 2 years and 8 months. He was born after a normal pregnancy at 39 weeks' gestation. He had unremarkable familial and prenatal history. Birthweight, length, and head circumference were within normal ranges. He experienced a cluster of seizures at 2 months old (five seizures a day). He developed infantile spasms at 3 months old without hypsarythmia. EEG activity consisted of bilateral high-amplitude slow waves intermixed with spikes on both central and left occipital regions. Hypotonia was noted. The patient was seizure-free on vigabatrin. Physical examination revealed hypotonia and psychomotor delay. At 14 months old, he developed tonic seizures, focal seizures, and epileptic spasms, and showed poor visual interaction. EEG recording showed hypsarythmia. Corticosteroids were ineffective. The last MRI study, at 2 years old, showed cerebral atrophy mainly of the white matter. Seizures have been partially controlled since ketogenic diet was started (at 2 years old) in addition to valproate, levetiracetam, and clobazam. At 2 years and 8 months, he presented with severe mental retardation. He was able to sit alone, but was unable to stand up without support. He had no language skills. Height was 91.5 cm, weight was 13 kg, and his head circumference was within the normal range (50th centile).

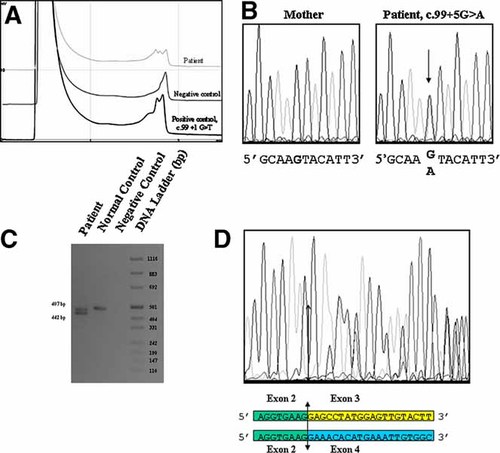

Blood samples were obtained after informed consent. Conventional cytogenetic investigations were normal. Genomic DNA from peripheral blood lymphocytes was screened for a mutation in the CDKL5 gene by dHPLC and indicated an abnormal dHPLC profile in exon 3 that was observed neither in his mother nor in more than 200 normal X chromosomes (Fig. 1A). Sequencing of the abnormal PCR fragment showed a new G > A base substitution at position +5 of exon 3 splice donor site (c.99 + 5G > A). This variant was unexpectedly observed at the heterozygous profile, with mutated and normal peaks that seem to be of similar intensity (Fig. 1B). After excluding a numerical aberration of X chromosomes (normal 46,XY karyotype), and a possible duplication by MLPA analysis of the CDKL5 gene, the results obtained from peripheral blood lymphocyte analysis suggested mosaicism for a somatic mutation. To confirm this mosaicism, DNA was extracted from a fibroblast culture from the patient, and similar results were obtained with about 50% of cells harboring the mutation. Complementary DNA generated from the fibroblast culture was PCR-amplified using primers flanking exon 3 and produced two fragments: a band that co-migrates with the control amplification and a 35 bp shorter band (Fig. 1C). Direct sequencing of this latter fragment showed exon 3 skipping (Fig. 1D). Deletion of exon 3 results in a frameshift of the CDKL5 coding sequence and is predicted to prematurely truncate the CDKL5 protein (24 amino acids, stop codon TGA at position 25). Complete abolition of normal splicing is the most common consequence of a mutation at the +5 donor site [Krawczak et al., 1992].

A: Denaturing high-pressure liquid chromatography (DHPLC) patterns of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products corresponding to exon 3 and adjacent intronic sequences: normal exon sequence (negative control); altered dHPLC profile due to the splice mutation (patient). B: Fluorescence sequence analysis of exon 3 and adjacent intronic sequence using the forward primers (mother and patient). The arrow indicates the position of the c.99 + 5G > A mutation in CDKL5 intron 3. C: Consequence of the splice mutation at the mRNA level. Analysis of CDKL5 mRNA extracted from fibroblasts by reverse-transcriptase-PCR: amplification product generated from the patient, from a normal control, and negative control without reverse-transcriptase. The last lane shows a DNA ladder (pUC mix8, Euromedex). D: Analysis of the aberrant transcript caused by the mutation c.99 + 5G > A by direct sequencing of the RT-PCR product. Overlapping sequences indicate the existence of both aberrant and normal transcripts, and shows the skipping of exon 3 in the aberrant transcript. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

To our knowledge, we show for the first time that somatic mosaicism for CDKL5 mutations in males may be not infrequent. Because ∼50% of cells carry the mutation not only in blood but also in tissues deriving from other cell lineages (such as fibroblasts), we may assume that the mutation event occurred at a very early stage of embryogenesis. If the mosaicism rate is low, we hypothesize that the ability of standard molecular methods (such as DNA sequencing) to detect mosaic mutations is poor, and that other complementary approaches such as methods based on heteroduplex analysis must be performed for an efficient screening of the CDKL5 gene in boys with severe encephalopathy and early-onset intractable seizures.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Institut National de la Santé et de Recherche Médicale and was supported by a grant from ANR-Maladies Rares (ANR-Maladies Rares ANR-06-MRAR-003-01, and ANR E-Rare EuroRETT Network).