A syndrome with multiple malformations, mental retardation, and ACTH deficiency

Abstract

We report on a patient with severe pre- and post-natal growth retardation, moderate mental retardation, microcephaly, unusual face with marked micrognathia and cleft palate, minor skeletal abnormalities, atrioseptal defect, hypospadias, hearing loss, and secondary adrenal insufficiency due to isolated ACTH deficiency diagnosed at 7 years of age. Family history was negative. Adrenal insufficiency is an uncommon feature in multiple malformation syndromes and may thus serve as a diagnostic handle for recognizing other possible patients with a similar syndrome. © 2003 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Uncommon syndrome features are an indispensable tool both for clinical dysmorphologists in search of a diagnosis and for researchers uncovering basic pathophysiologic mechanisms resulting in a particular phenotype. Adrenal insufficiency can develop through several different mechanisms, but regardless of its etiology has been described in only a handful of multiple malformation syndromes. We report on a patient with a hitherto undescribed combination of features including severe growth retardation of intrauterine onset, moderate mental retardation, microcephaly, marked micrognathia with cleft palate, unusual face, minor skeletal abnormalities, atrioseptal defect, hearing loss, and secondary adrenal insufficiency due to isolated ACTH deficiency diagnosed at 7 years of age.

CLINICAL REPORT

The child was born from a twin pregnancy of a 38-year-old G2P1 mother and a 41-year-old father. Family history was unremarkable with no evidence of consanguinity. In week 11 of gestation, a marked difference was noted in size of the fetuses. By amniocentesis on week 16, the karyotype of both fetuses was normal, but the amniotic fluid alphafetoprotein concentration in the smaller fetus was elevated (53,000 IU/L, upper limit of normal range 25,600 IU/L).

Progressive intrauterine growth retardation and a monotonic cardiotocogram prompted cesarean section on week 35 of gestation. Birth weight was 930 g (−5.5 SD), birth length 36 cm (−6.5 SD), and head circumference 27 cm (−4.5 SD), with the corresponding measurements of the larger male twin being 2,440 g (−1.0 SD), 47 cm (−0.1 SD), and 33.5 cm (+0.2 SD). The placenta was common, with separate chorions and no sign of placental insufficiency or fetofetal transfusion.

Because of relative upper airway obstruction associated with an extremely small mandible and cleft palate, the child was intubated with his own respiration for the first week of life. A patent ductus arteriosus closed after the second indomethacin treatment, and subsequently an atrioseptal defect of secundum type was noted. Early post-natal hypoglycemia did not recur after 4 days of age. At 3 weeks, two episodes of convulsions occurred during normal blood glucose levels, and an EEG at 5 weeks was normal. Facial features were dysmorphic (Fig. 1). Midline and genital defects and early hypoglycemia prompted endocrine tests at 2–3 months, with no abnormalities found (Table I). Because of treatment with inhaled budesonide, ACTH test was repeated at 2 years, showing a normal result.

Face during neonatal period. Note extremely small mandible, wide nasal bridge and tip, and short palpebral fissures. The build is slender, with almost nonexistent subcutaneous fat.

| 2–3 Months | 2 Years | 7 Years | 8 Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard dose (250 μg/1.7 m2 body surface area) ACTH test; cortisol (nmol/L) at 0–60–120 min | 2,156a | 260–1,377–1,533 | 105–415–418 | |

| Low dose (1 μg/1.7 m2 body surface area) ACTH test; cortisol (nmol/L) at 0–30 min | <20–25 | |||

| Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH test (1 μg/kg) | ||||

| Cortisol (nmol/l) at 0–20–40–50–60 minb | <20–<20–<20–<20–<20 | |||

| ACTH (ng/L) at 0–20–40–50–60 minb | 8–14–17–18–20 | |||

| Interpretation | Normal | Normal | Suggestive of adrenal insufficiency | Confirms central adrenal insufficiency, possibly at pituitary gland level |

- Endocrine tests with normal results include growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) tests at 2 months of age, luteinizing hormone (LH) test at 2 years, clonidine–arginine test at 7 years, and serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-3, thyrotropin (TSH), free thyroxin (T4) concentrations, and plasma renin at 8 years.

- a Cortisol concentration at 60 min.

- b A rise greater than four-fold from baseline is considered a normal response [Lytras et al., 1984].

Due to respiratory and feeding difficulties, the child was a hospital inpatient most of the time until 26 months of age. He had a tracheostomy cannula from 18 to 26 months and a gastrostomy from 14 months to 5 years. The reason for the feeding difficulty remained obscure while no motor difficulty in swallowing was noted by videofluorography at 22 months. Development was delayed with a walking age of 3 years 6 months and first words at 4 years. At 8 years, the child with moderate MR communicated with several-word sentences and supportive sign language. An audiogram at 5 years showed bilateral sensorineural hearing loss with a hearing threshold of 55 dB. Operations performed include palatoplasty, repeated tympanostomies, funiculolysis, and orchiopexy because of undescended testes, and excision of a prominent coccyx.

From 6 years, the child experienced six hypoglycemic episodes with blood glucose down to 1.1 mmol/L, most of these presenting with convulsions. After a normal 24-hr EEG and ECG and exclusion of hyperinsulinemia and fatty acid beta-oxidation defects by a 19-hr fasting test and normal acylcarnitine profile, relative adrenal insufficiency was suggested by low cortisol after a standard (250 μg) ACTH stimulation test (Table I). No systemic glucocorticoids had been given before the hypoglycemic episodes, but for several years the patient had received regular inhaled budesonide 500 μg/d by nebulizer. After the start of hydrocortisone replacement therapy, no hypoglycemic symptoms have occurred. A low-dose (1 μg/1.7 m2) ACTH test was performed after interruption of the treatment at 8 years, indicating almost total loss of cortisol secretion (Table I). A corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) test revealed subnormal basal ACTH secretion and poor response to CRH (Table I), thus pointing to ACTH deficiency as the cause of adrenal insufficiency. No defects were found in the synthesis of any other pituitary hormone (Table I).

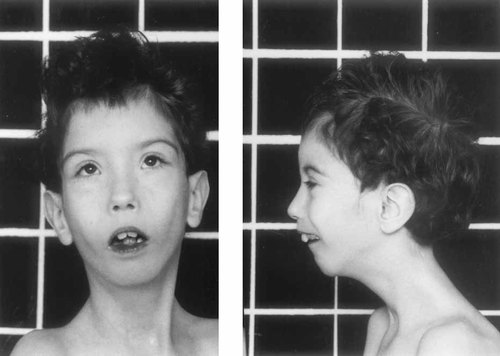

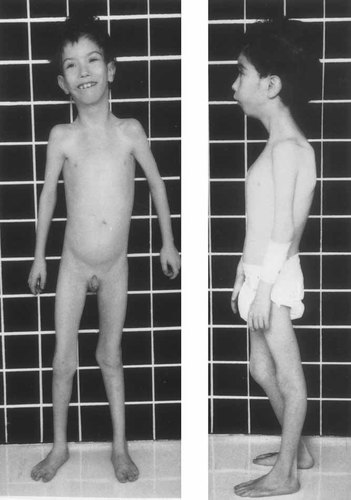

On examination at 8 years 3 months, height was 112.2 cm (−3.2 SD), weight 14.7 kg (25% below mean for corresponding height), and head circumference 47 cm (−4.3 SD), with multiple dysmorphic features (Figs. 2 and 3). His face appeared expressionless, but he was able to smile, frown, and raise his eyebrows. Both truncal and peripheral muscles were thin and hypotonic, but the patient was able to jump with both feet and raise from squatting position without difficulty. Tendon reflexes were normal. In addition, the right little finger had a stiff PIP joint and a small nail, mild soft tissue syndactyly was evident between all fingers as well as toes II–III, and the V toes were hypoplastic. The gums were hypertrophic. Ophthalmologic examination revealed mild hyperopia (+2.5/+3.0) and an inward deviating strabismus with otherwise normal eye movements and no signs of abducens palsy. Fundoscopy was normal apart from tortuosity of arterioles of the peripheral retina.

At 8 years of age, the face is slightly asymmetric, with more pronounced maxillary hypoplasia on the left. The mandible is still small and the face and forehead narrow. Hypertelorism is accompanied by somewhat short, upward slanting palpebral fissures. The low-set ears with a thin helix are also apparent.

The patient at 8 years of age. Note the slender build, pectus carinatum, laterally placed mamillae, and hypoplastic V toes.

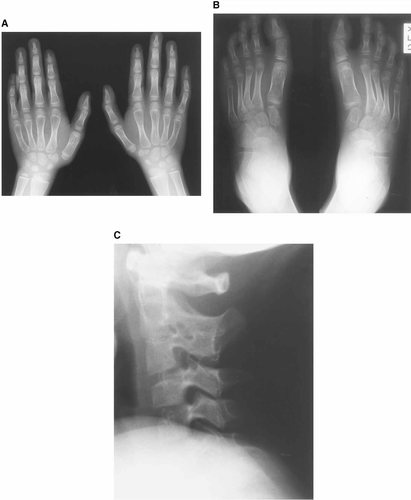

A prometaphase chromosome study was normal 46,XY, and no chromosomal rearrangement was noted in FISH analysis with either a chromosome arm-specific subtelomeric or a chromosome-specific multicolor probe set. Radiographs at 7 years revealed block vertebrae CII–CIII and hypoplastic V fingers and toes (Fig. 4). Cranial MRI at 9 years showed moderate, diffuse cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, the hypophysis and hypothalamus, however, being normal. Abdominal ultrasound was normal. Normal laboratory tests included serum creatinine kinase, very-long-chain fatty acids, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, total cholesterol, serum cholesterol precursors, and urinary amino acid, oligosaccharide, glycosaminoglycane, and organic acid screen. Molecular testing for myotonic dystrophy showed no expansion of the CTG trinucleotide repeat in the DMPK gene.

Radiographs of hands and feet, and lateral view of cervical spine at 8 years of age. Hypoplasia of the distal phalanges of V fingers is evident, with aplasia/hypoplasia of the medial and distal phalanges of V toes. The II and III cervical vertebrae are fused. Bone age according to the Greylich-Pyle method is 8 years.

DISCUSSION

This patient represents a unique combination of congenital malformations, mental retardation, and adrenal insufficiency due to isolated ACTH deficiency. Despite the fact that upper airway obstruction and feeding difficulties required hospitalization for most of his first 2 years of life, the child does well at 9 years of age with his handicaps and continues learning new skills. As the family history was negative, there is no clue as to mode of inheritance of this syndrome. Prometaphase chromosomes as well as FISH techniques using chromosome and subtelomere specific probes have failed to show any abnormality, and although a submicroscopic chromosomal abnormality cannot be excluded, a number of defined syndromes share essential features with those of our patient, suggesting the possibility of a single-gene etiology.

Severe growth retardation of intrauterine onset, microcephaly, short palpebral fissures, and micrognathia possibly associated with cleft palate and/or teeth malocclusion are characteristic features of Seckel syndrome [Majewski and Goecke, 1982; Thompson and Pembrey, 1985]. However, our patient has features not associated with Seckel syndrome such as fusion of cervical vertebrae, hypoplasia of the V finger and toes, an atrioseptal defect, and hearing loss, and he lacks the hallmark of this syndrome, a large beaked nose.

His facial dysmorphology is reminiscent of a number of other differential diagnoses. In particular hypertelorism, short palpebral fissures, small nose, micrognathia with cleft palate, and low-set ears, point to Toriello–Carey syndrome, which is also characterized by mental retardation, hypospadias, and cardiac and vertebral defects [Toriello and Carey, 1988; Wegner and Hersh, 2001; Kataoka et al., 2003]. However, the severe prenatal growth retardation and the absence of corpus callosum agenesis in our patient make this diagnosis unlikely. Facial features were reminiscent of cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal (COFS) syndrome, but there was no microphtalmia, cataract, and optic atrophy usually present in COFS patients [Graham et al., 2001], and his psychomotor retardation was milder. Short palpebral fissures, expressionless face, and micrognathia with cleft palate suggest Marden–Walker syndrome, which can however, be excluded by the absence of true blepharophimosis and contractures at birth [Williams et al., 1993].

The most unique feature of our patient is adrenal insufficiency which is due to a central defect at either the pituitary or hypothalamic level. The adrenal insufficiency is most likely acquired. The patient did not suffer from hypoglycaemia until the age of 6, apart from the first post-natal days when hypoglycemia is frequent especially in growth retarded newborns, and in particular no hypoglycemia was found during the convulsions at 3 weeks. In infancy, his cortisol secretion after ACTH stimulation was normal or even supranormal. The ACTH stimulation tests revealed a rapid decline in hypothalamic-pituitary-axis function after age 6. His severe hypoglycemic attacks were completely prevented by hydrocortisone treatment, demonstrating that their major cause was adrenal insufficiency. The CRH test can be used to define the level of adrenal failure, hypothalamic ACTH deficiency being generally associated with an exaggerated ACTH response [Grinspoon and Biller, 1994]. In our patient, it was obvious that ACTH secretion was much reduced for the hypocortisolic state, and even after CRH stimulation it remained in the low range. This result fits best with pituitary ACTH deficiency, although a hypothalamic defect cannot be entirely ruled out because a two-fold delayed response occurred in ACTH secretion. Moreover, the ACTH deficiency of our patient can be classified as isolated because no defect was detected in the synthesis of any other pituitary hormone.

In association with multiple malformations, adrenal insufficiency has been described in only a small number of clinical entities. Of these, the IMAGe association [Vilain et al., 1999] and an Xp21 continuous gene syndrome disrupting the adrenal hypoplasia congenita (AHC) gene [Mc Cabe, 2001] present with profound neonatal-onset adrenal insufficiency, in contrast to the situation in our patient, who showed only relative late-onset hypocortisolism. Burke et al. [1988] described three newborns with congenital adrenal hypoplasia, who in contrast to our patient were not growth retarded and had undetectable luteinizing hormone levels. Syndromes associated with relative adrenal insufficiency include achalasia-addisonialism-alacrima (AAA) syndrome [Moore et al., 1991], which is easily excluded in our patient, who showed neither achalasia nor tear abnormalities. In addition, adrenal insufficiency with a hypothalamic or pituitary component has been reported in three patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome [SLOS; Andersson et al., 1999], which has, however, been ruled out by a normal serum cholesterol precursor profile.

We conclude that the combination of features in our patient is likely to represent a new syndrome with acquired isolated ACTH deficiency as its key characteristic. We recommend vigilant assessment of adrenal function when patients with related phenotypes present with unexplained symptoms, not only to allow the detection of possible new cases but also to detect a life-threatening yet remediable condition.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Helga V. Toriello for valuable comments on diagnosis of this patient.