The velocity of fetal growth is associated with the breadth of the placental surface, but not with the length

ABSTRACT

Objectives

Studies of the placenta in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia have led to the suggestion that tissue along the length and breadth of its surface has different functions. A recent study in Saudi Arabia showed that the body size of newborn babies was related to the breadth of the surface at birth but not to its length. We have now examined whether the association between placental breadth and body size reflects large size of the baby from an early stage of gestation or rapid growth between early and late gestation.

Methods

We studied 230 women who gave birth to singleton babies in King Khalid Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In total, 176 had ultrasound measurements both before 28 weeks and at 28 weeks or later, which we define as early and late gestation. We used these to calculate growth velocities between early and late gestation, which we expressed as the change in standard deviation scores over a 10-week period.

Results

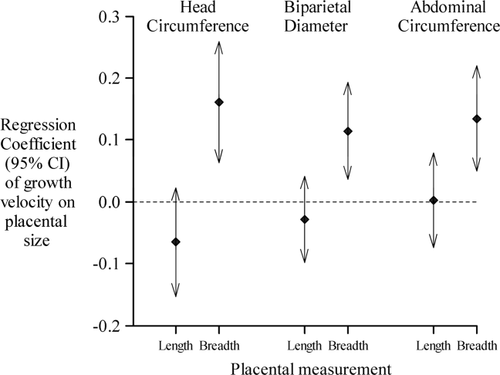

The breadth of the placental surface was correlated with fetal growth velocity. The correlation coefficients were 0.24 (P = 0.002) for the head circumference, 0.24 (P = 0.001) for the biparietal diameter and 0.34 (P < 0.001) for the abdominal circumference. The length of the surface was not related to fetal growth velocity.

Conclusions

Tissue along the breadth of the placental surface may be more important than tissue along the length in the transfer of nutrients from mother to baby. This may be part of a wider phenomenon of regional differences in function across the placental surface. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 25:534–537, 2013. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

The weight of the human placenta at birth is related to the weight of the baby. Large babies generally have large placentas. Weight, however, is a crude measure of placental size because it does not distinguish the size of the placental surface from its thickness. In the past, the length and breadth of the surface were routinely measured in some hospitals, because the surface was recognized as being oval rather than round (Anderson, 1930; Mays, 1930). In the two maternity hospitals in Helsinki, Finland, these measurements are available for the 20,000 men and women who were born during 1924–1944 and who comprise the Helsinki Birth Cohort (Kajantie et al., 2010). This cohort has been followed up through their lives. In the cohort, the placental surfaces of babies born after pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia had reduced breadth but not reduced length, and hence had a more oval surface than those from normotensive pregnancies (Kajantie et al., 2010). The relationship between the breadth and the pre-eclampsia was graded; the shorter the breadth the higher the incidence of preeclampsia. This association depended on the absolute size of the breadth rather than on its size in relation to the surface area or weight. Processes that underlie pre-eclampsia therefore seem to be closely linked to the amount of tissue on the breadth. This link may be through structures or functions that it does not share with tissue along the length.

The size of the breadth and length are associated with different disorders in later life. Short breadth is associated with the later development of coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure, hypertension, and lung cancer (Barker et al., 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Eriksson et al., 2011). In contrast, asthma among adults (unpublished) and Hodgkin's lymphoma are associated with the length but not with the breadth (Barker et al., 2013). These long-term associations are thought to reflect fetal programming, the phenomenon by which nutrition and other influences during development permanently set the structure and function of the body's organs. The different programming associations of breadth and length suggest that tissue along these two axes has different functions. The growth of the baby may therefore relate differently to the two axes.

Findings in a recent study in Saudi Arabia support this (Alwasel et al., 2012). Among 401 neonates, the breadth and length of the placental surface were highly correlated (coefficient = 0.7). Nevertheless, in a simultaneous regression of both measurements only the breadth was associated with neonatal body size. In a subsample of the babies, serial ultrasound examinations were carried out and we are therefore able to relate placental size at birth to fetal growth velocities. This has enabled us to determine whether the association between placental breadth and body size at birth reflects rapid growth from an early stage in gestation or accelerated growth between early and late gestation.

METHODS

We studied pregnant Saudi women who attended King Khalid Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for maternity care between July 2009 and June 2010 and who gave birth to singletons (Alwasel et al., 2012). We used the date of the last menstrual period to calculate gestational age. Women in Saudi Arabia are careful in knowing their menstrual cycles as menstrual bleeding affects religious practices.

In total, 230 babies had ultrasound measurements. 176 had measurements both before 28 weeks and later, which we defined as early and late gestation. It was, therefore, possible to calculate the velocity of fetal growth. There were no differences between the placental and the maternal characteristics of the 176 babies whose growth velocity was known and the 54 in whom it was not known. The ultrasound examination included measurements of the head circumference, biparietal diameter, and abdominal circumference. At birth, we measured the body size of the baby, including its weight, head, and abdominal circumferences. The cord was cut flush with the placenta, and clots were removed. The placenta was weighed using an electronic scale. The length of the surface was defined as the longest diameter on the maternal side; and the breadth as the longest diameter at right angles to the length (Kajantie et al., 2010). Our protocol was a standard protocol used in other studies (Winder et al., 2011). The King Khalid Hospital Ethical Committee gave permission for the study.

Statistical methods

Each subject had two to four ultrasound examinations. We used each measurement to construct growth centile charts for head circumference, biparietal diameter, and abdominal circumference. Each measurement was thereby expressed as a standard deviation score. Among the 176 subjects with ultrasounds in both early and late gestation, defined as <28 weeks and 28 weeks or more, we used the first and last measurements to calculate growth velocity, which was expressed as change in z-score over 10 weeks. We used multiple linear regressions to examine the magnitude of the trends in fetal size and growth velocity during gestation with neonatal size and placental size. To examine the simultaneous associations between fetal size and placental length and breadth, we used linear regressions in which length and breadth were included together as predictors. We used continuous variables in conducting tests for trend.

RESULTS

Table 1 lists the mean measurements of the mothers, the velocities of fetal growth, and the size of the babies and placentas at birth. The mean placental and neonatal measurements are similar to western values. Table 2 lists the correlation coefficients between the three ultrasound measurements, head circumference, biparietal diameter, and abdominal circumference, and three neonatal measurements. A large head circumference in late gestation, and large biparietal diameter in early and late gestation, predicted a large head circumference at birth. High growth velocities in head circumference and biparietal diameter also predicted a large neonatal head circumference. Similarly, a large abdominal circumference in late gestation and a large velocity in growth of the abdominal circumference predicted a large neonatal abdominal circumference. Large values of all three ultrasound measurements in late gestation, and high growth velocities, predicted high birth weight.

| Measurement | Mean | St. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal measurements | ||

| Age (years) | 29.4 | 6.1 |

| % Primiparous | 39 | |

| Height (cm) | 156.2 | 5.9 |

| Body mass index at booking (kg/m2) | 28.7 | 6.1 |

| % University educated | 58 | |

| Pregnancy weeks at ultrasound | ||

| First measurement | 20.6 | 3.8 |

| Last measurement | 35.4 | 2.9 |

| Velocity of fetal growth (Δz per 10 weeks) | ||

| Head circumference | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Biparietal diameter | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Abdominal circumference | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Neonatal measurements | ||

| Weight (g) | 3182 | 509 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 34.0 | 1.5 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 30.6 | 2.8 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.0 | 1.7 |

| Placental measurements at birth | ||

| Weight (g) | 584 | 121 |

| Breadth (cm) | 17.3 | 1.7 |

| Length (cm) | 19.3 | 1.9 |

| Length–breadth (cm) | 2.0 | 1.4 |

| Ultrasound measurement | Neonatal measurement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head circumference | Abdominal circumference | Weight | ||

| Head circumference | Early | 0.130 | 0.053 | 0.045 |

| 0.070 | 0.465 | 0.533 | ||

| Late | 0.432 | 0.261 | 0.308 | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Velocity | 0.324 | 0.220 | 0.261 | |

| <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | ||

| Biparietal diameter | Early | 0.143 | 0.032 | 0.027 |

| 0.042 | 0.649 | 0.702 | ||

| Late | 0.431 | 0.239 | 0.298 | |

| <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Velocity | 0.262 | 0.246 | 0.242 | |

| 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Abdominal circumference | Early | 0.168 | 0.131 | 0.115 |

| 0.023 | 0.076 | 0.123 | ||

| Late | 0.375 | 0.393 | 0.415 | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Velocity | 0.271 | 0.441 | 0.430 | |

| 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

- a P-values are indicated in italic fonts.

Table 3 lists the correlation coefficients between the three ultrasound measurements and the breadth and length of the placental surface at birth. A large placental breadth was associated with high growth velocities in head circumference, biparietal diameter, and abdominal circumference. A large placental length was not associated with growth in head circumference or biparietal diameter, but it was associated with high velocity in growth of the abdominal circumference. We examined the simultaneous associations of placental breadth and length with fetal growth velocity. The trends with breadth remained statistically significant, but there were no trends with length (Fig. 1). The trends with breadth were similar in primiparous and multiparous mothers and did not vary with maternal age.

| Ultrasound measurement | Placental measurement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Breadth | Length | ||

| Head circumference | Early | −0.084 | 0.059 |

| 0.242 | 0.411 | ||

| Late | 0.090 | 0.081 | |

| 0.208 | 0.257 | ||

| Velocity | 0.239 | 0.088 | |

| 0.002 | 0.264 | ||

| Biparietal diameter | Early | −0.099 | −0.013 |

| 0.162 | 0.856 | ||

| Late | 0.156 | 0.120 | |

| 0.029 | 0.093 | ||

| Velocity | 0.243 | 0.128 | |

| 0.001 | 0.095 | ||

| Abdominal circumference | Early | −0.024 | 0.024 |

| 0.743 | 0.744 | ||

| Late | 0.228 | 0.208 | |

| 0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| Velocity | 0.342 | 0.246 | |

| <0.001 | 0.002 | ||

- a P-values are indicated in italic fonts.

Maternal characteristics

We examined the effects of maternal characteristics on fetal growth velocity. The fetuses of older mothers had more rapid growth in biparietal diameter (P = 0.01) and abdominal circumference (P = 0.005). Increasing parity was associated with more rapid growth in abdominal circumference (P = 0.04). Greater maternal height was also associated with more rapid growth in abdominal circumference (P = 0.003). When mother's age, parity, and height were added to the simultaneous regression of placental breadth and length on fetal growth velocity, the findings for the effects of breadth were little changed, whereas length remained without effect on fetal growth velocity. In our previous analyses of neonatal measurements, we divided the mothers around their mean height (Alwasel et al., 2012). In this analysis, the findings are similar in babies born to short and tall mothers. Fetal growth velocities were not related to mother's educational level or her body mass index (weight/height2) at booking.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that the body size of newborn babies in Saudi Arabia is related to the size of the breadth of the placental surface but not to the size of the length (Alwasel et al., 2012); the larger the breadth the larger the baby. We have now shown that a larger breadth is associated with a greater velocity of growth of the head and abdomen between early and late gestation, but is not associated with the size of the baby in early gestation. Higher velocities of growth of the head and abdomen were associated with higher birth weight; but birth weight was not associated with size in early gestation. These findings suggest that a larger breadth of the placental surface is associated with higher birth weight because it is associated with a greater growth velocity between early and late gestation rather than greater body size from early gestation. The size of the placental breadth may therefore reflect nutrient delivery to the fetus through gestation, rather than events during implantation and early placental development.

The associations between placental surface breadth and fetal growth velocity were independent of mother's age, parity, and height, which also influence the velocity. Our findings give an additional insight into the functional differences in tissue along the breadth and length of the placental surface. This was first suggested by the studies of pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia (Kajantie et al., 2010) and may be part of a wider phenomenon of regional differences in function across the surface. This is a new concept and has not yet been investigated at a cellular or molecular level. The trajectory of human fetal growth is established around the time of conception and determines the baby's demand for nutrients through gestation (Harding, 2001). These demands are at their highest in late gestation when the mother and placenta may or may not be able to meet them. One hypothesis is that tissue along the breadth is more important than tissue along the length in the transfer of nutrients from mother to baby, and hence in meeting fetal demands. Our findings are consistent with this as the size of the breadth is not related to growth in early gestation but rather to the velocity of growth between early and late gestation. The ability of the breadth to transfer nutrients may be determined by the amount of tissue along it. Another possibility is that the shape of the placental surface at birth is a marker of its overall effectiveness in nutrient transfer; and a placenta in which the breadth has failed to grow in relation to the length, and which therefore has a more oval surface, is less effective.

There is evidence that, in addition to responding to fetal demands, tissue along the breadth of the placental surface responds to changes in maternal diet. Among men born around the time of the war-time famine in Holland, a large placental breadth predicted later hypertension among those who were in utero during the 7 months famine. In contrast, it was a small placental breadth that predicted later hypertension among those who were in utero before or after the famine (van Abeelen et al., 2011). Tissue along the breadth therefore seems to program the baby differently according to the mother's diet.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study was limited to an unselected sample of pregnant women attending a maternity hospital in Riyadh. In total, 58% of the mothers had received university education, which would not be typical of Saudi Arabia as a whole. The measurement of the length and breadth of the placental surface at birth were made by midwives trained to do this in accordance with a protocol used in other studies. The strong correlations between the velocities of fetal growth measured by ultrasound and size at birth measured by the midwives, including birth weight (Table 2), validate these measurements.

CONCLUSIONS

Tissue along the breadth of the placental surface may be more important than tissue along the length in the transfer of nutrients from mother to baby. This may be part of a wider phenomenon of regional differences in function across the placental surface.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the staff of the Maternity Unite at King Khalid Hospital for their help with this study. The study was funded by the distinguished fellowship program, King Saud University.