Clinical and biological characterization of involvement of nasal-associated lymphoid tissues in chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are prone to infectious complications, including ear, nose, and throat (ENT) infections, due to humoral immunodepression and/or immunosuppression related to therapy. However, specific CLL infiltration in nonlymphoid regions of the head and neck causing ENT symptoms but unrelated to an infection has not been described. CLL is a disease of lymphoid organs, but recent studies have reported extranodal localization of the disease involving the skin and the lungs.1, 2 Here, we report a series of cases with specific localizations of CLL cells into the mucosa of the rhinopharynx manifesting as symptoms of ENT infection. To gain insight into the characteristics of this entity of CLL, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical, histological, and molecular features of 25 patients with specific ENT involvement.

All patients were followed in the Hematology Department for proven CLL, and they began to present ENT manifestations at a median time after CLL diagnosis of 2.5 years [1–11 years]. At time of the first ENT symptoms, all patients presented and elevated absolute lymphocyte count (mean at 33 × 109/L [9–117]) and an involvement of the lymphoid areas with enlarged lymph nodes and/or splenomegaly in virtually all cases (21 patients, 83%). ENT symptoms included chronic coughing (44%), antero-posterior nasal discharge (44%), nasal congestion (33%) and pharyngitis (33%). These symptoms were related to upper airway infections, but the manifestations were recurrent and persisted after antibiotic therapy. Thorough ENT examination was carried out and revealed an unusual granular aspect of the mucosa in more than half of the cases (56%), showing pavimentous lesions, thickened, swollen, salmon-colored, and localized mostly at the posterior pharyngeal wall.

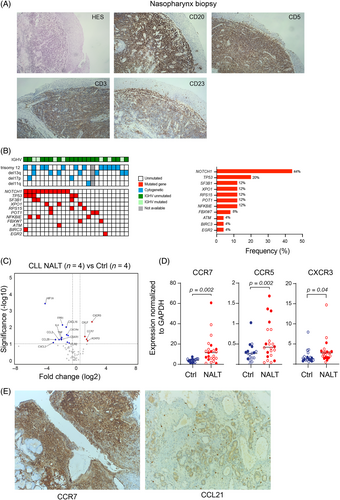

Given the persistence of ENT symptoms despite antibiotic treatment and without signs of infection, all patients underwent biopsy of the nasal or pharyngeal mucosa (oropharynx in 17 cases, nasopharynx in five cases, tonsils in three cases, and sinuses in two cases). Histology and immunochemistry analysis showed infiltration of small lymphocytes with CLL phenotype expressing the CD20, the CD5 and the CD23 markers. The pattern of infiltration was diffuse in 63% of the cases and perivascular in 37% (Figure 1A), consistent with specific involvement of CLL cells in nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT-CLL).

Regarding the clinical outcome of the patients with NALT-CLL, most of them had poor prognostic features. The majority of the cases were IGHV unmutated (n = 18/25, 72%). No bias of the IGHV repertoire and no CDR3 stereotype was detected. Furthermore, all cases progressed according to International Workshop on CLL criteria (i.e., development of, or worsening of, anemia and/or thrombocytopenia, progressive or symptomatic splenomegaly and/or lymphadenopathy, lymphocyte doubling time <6 months).3 For 13 patients, the manifestations were diagnosed before frontline treatment and they needed to be treated within 2 years after the first ENT symptoms. For the 12 remaining patients, the ENT symptoms occurred at relapse. This indicates that NALT-CLL is associated with disease that is more progressive. Interestingly, the systemic treatment led to a complete regression of the nasopharyngeal symptoms in all patients, further confirming the clonal relation between the ENT lesions and the hematological disease.

To characterize the genetic background of NALT-CLL, we analyzed cytogenetic data and NGS-targeted sequencing for 13 genes in circulating CLL cells (Figure 1B, Table S1). The karyotype was normal in only 2/24 cases (8%) and complex (>3 abnormalities) in 5/24 cases (20%). Half of the patients had trisomy 12 (12/24; 50%); 13q, 17p, and 11q deletions were found in 29%, 8%, and 4% of patients, respectively. A total of 11 patients harbored one mutation (44%), and nine patients carried two to five mutations. TP53 and SF3B1 mutations occurred in 20% (5/25 cases) and 12% (3/25 cases), respectively. Mutations of NOTCH1 pathway components were found in half of the cases (11/25 NOTCH1 and 2/25 FBXW7 mutated cases). Notably, 75% of patients (n = 18/24) had a NOTCH1 abnormality and/or trisomy 12. Similarly, a high frequency of NOTCH1 mutation (34%) and trisomy 12 (29%) has been reported in CLL with specific skin infiltration, while it usually accounts for 5%–10% of patients with CLL at diagnosis and approximately 20% when considering those treated with immunochemotherapy.1, 4, 5 This observation raises the question of the role of NOTCH1 mutation and trisomy 12 in extranodal localization of tumor cells.

To gain insight into the molecular mechanism associated with rhinopharyngeal involvement, we screened expression of a set of 70 genes related to cell migration and cell adhesion pathways using a qPCR array in the peripheral CLL cells of patients with NALT (n = 4) compared with no NALT-CLL (n = 4) (Table S2). Genes significantly upregulated with a fold change >2 included the C-C motif chemokine receptor CCR7 (p = 0.05), the C-X motif receptor involved in leukocyte trafficking CXCR3 (p = 0.01) and the chemoattractant chemokine-like factor CKLF. Among the most downregulated genes, we found the gene encoding the hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha HIF1A, and genes encoding chemokines such as the chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 28 (CCL28) and 3 (CCL3), the interleukine 4 (IL4), the chemokine (C-X motif) ligand (CXCL16), and the tumor necrosis factor (TNF). By targeted qPCR, we confirmed upregulation of CCR7 (p = 0.002), CXCR3 (p = 0.04), and CCR5 (p = 0.03) in the series of 25 NALT-CLL patients compared to 20 age-matched CLL patients without head and neck symptoms (77% with unmutated IGHV, 30% with NOTCH1 mutation and 30% with trisomy 12) (Figure 1C). Upregulation of those targets appeared to be independent of the presence of NOTCH1/trisomy12 aberration or IGHV mutation status, except for CCR5 which was slightly upregulated in the IGHV mutated subgroup (p = 0.04) (Figure S1). In line with these results, immunohistochemistry analysis for five patients with nasal involvement showed strong staining of the CCR7 marker on the membrane of CLL cells infiltrating the mucosa (Figure 1D). The CCR7 receptor is usually expressed on the membrane of CLL cells, and it plays a pivotal role in cell endothelial transmigration within the lymph node in response to binding of CCL19 and CCL21 produced by cells of the microenvironment.6 Interestingly, staining for CCL21, the cognate ligand of CCR7, was positive in the high endothelial venules (HEVs) of the nasal mucosa (Figure 1E).

The microenvironment of the rhinopharynx is not a usual niche for CLL cells. Nasal lymphoid tissue forms a unique gateway that plays a central role in induction of local and systemic responses to a wide range of pathogens and allergens. It is composed of T and B cells organized in follicle-associated epithelium, dendritic cells, microfold cells, and macrophages, surrounded by lymphatic vessels and HEVs.7 Activated pathogen-recognition receptors in the mucosa induce release of leukocyte-recruiting cytokines and lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation to promote the immune response.8 We can therefore hypothesize that localization of CLL cells within the NALT relies on similar mechanisms of cell migration as in lymph nodes, involving interplay between the chemokines produced by the mucosa and matching receptors on CLL cells. In lymph nodes, CCL21 is a potent B-cell chemoattractant expressed by HEVs, nurselike cells (NLCs) and follicular reticular cells in the T-cell zone (FRCs) and plays a pivotal role in driving cell entry and motility in interstitial lymph nodes, favoring their interaction with T cells expressing CD40L.6, 9, 10 The presence of CCL21-positive staining in the vessels associated with perivascular distribution of CLL cells in the mucosa strongly supports the hypothesis of either a mechanism of CCL21/CCR7-driven migration in patients with ENT localization, or an enhanced signal of CLL cells retention provided by the CCR7 in the vicinity of the CCL21-expressing HEVs cells. Similarly, it has been shown that expression of CCR7 by CLL cells is significantly higher in patients presenting with lymphadenopathy, suggesting a higher migration capacity and retention within the lymphoid niche.6 Finally, it has been demonstrated that NOTCH1 activation or mutation increases expression of CCR7 to promote chemotaxis by suppressing the tumor-suppressor gene DUSP22.11 In our series, NOTCH1 was the most frequently mutated gene, which might enhance migration within the nasal mucosa through upregulation of the CCR7 receptor. However, the absence of significant correlation between CCR7 expression and NOTCH1 mutation suggests that other mechanisms might be involved.

To conclude, we report here cases of specific rhinopharyngeal localization of CLL associated with ENT symptoms. This atypical presentation of CLL is often encountered in patients with progressive disease. It is important to raise awareness among clinicians of the existence of these specific localizations, as their presence should lead to a consideration for faster treatment of CLL, as opposed to delaying it by giving repetitive antibiotic treatment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Florence Cymbalista, Fanny Baran-Marszak, and Gregory Lazarian. Acquisition of data (acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): Thimali Ranaweera Arachchige, Florence Cymbalista, Fanny Baran-Marszak, Catherine Mendiburu, and Gregory Lazarian. Analysis and interpretation of data: Thimali Ranaweera Arachchige, Florence Cymbalista, Fanny Baran-Marszak, and Gregory Lazarian. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: Thimali Ranaweera Arachchige, Antoine Martin, Carole Fleury, Elisabetta Dondi, Rémi Letestu, Virginie Eclache, Catherine Mendiburu, Fanny Baran-Marszak, Florence Cymbalista, Gregory Lazarian. Study supervision: Florence Cymbalista, Fanny Baran-Marszak and Gregory Lazarian.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Informed consent was obtained in each case before cells were collected.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data are provided in the manuscript & supplementary files.