Management of front line chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Continuing Medical Education: Please Click Here to complete an accredited learning activity for this article and receive 1.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

Abstract

Treatment options with targeted agents have changed the treatment landscape of CLL profoundly. Besides chemoimmunotherapy, treatment regimen approved for frontline therapy include continuous treatment with BTK inhibitors like ibrutinib and acalabrutinib or fixed-duration regimen like venetoclax-obinutuzumab with the approval of venetoclax-ibrutinib to be awaited. Although these agents have usually manageable side effects, toxicities might limit choices for the individual patient. We here discuss latest trial data and propose a treatment algorithm for frontline treatment of CLL according to fitness and relevant genetic risk factors like IGHV mutational status and TP53 aberrations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common adult leukemia with an age adjusted incidence rate of 4.9 per 100 000 inhabitants.1 CLL is diagnosed mostly in elderly patients in the age group of 65–74 and with a median age of 70 years. Only 1.8% of the patients are under the age of 45 years.1 Hence, physical constitution can vary from very fit over unfit with relevant comorbidities to frail patients where treatment has to be chosen with particular care and consideration.

The WHO classifies CLL as indolent B-cell lymphoma, but the course of disease can vary from indolent to more aggressive. There are certain genetic and clinical risk factors that are proposed to be determined before start of therapy to predict how aggressive the course of disease might be2 of which the most prognostic factors have been combined in the CLL-IPI.3 This weighted score includes age, Binet/Rai stage, beta-2-mikroglobulin, immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region gene (IGHV) mutational status and TP53 status and discriminates four risk groups with different overall survival, but the data set contained only data from phase 3 trials with chemoimmunotherapy. In addition, dynamic on and post treatment factors such as minimal residual disease (MRD) are not considered, therefore, the continuous individualized risk index (CIRI) is being evaluated and adapted for targeted treatment of CLL.4, 5 Current therapy algorithms comprise deletion 17p (del17p)/mutation TP53 (mutTP53) and unmutated IGHV as indicators for a more aggressive course of disease.6

Several parameters are suggested to be considered when choosing the optimal regimen for the individual patient. These include clinical stage, symptoms of the patient, fitness, comorbidities and genetic risk factors.7-9

Frontline therapy for CLL has undergone profound changes within the past years when treatment options with targeted agents emerged. With the broader range of agents, the clinician can make a more individual choice for each patient and specific side effects of the different regimens can be taken into account. Toxicities of the targeted agents are usually manageable, but they also exhibit specific side effects like cardiac events10-14 and bleeding15, 16 for ibrutinib and other BTK inhibitors17, 18 as well as tumor lysis syndrome and infections for venetoclax.19, 20 As BTK inhibitors are given continuously, there is a risk of accumulation and aggravation of side effects. The traditional use of chemoimmunotherapy was a time limited therapy due to toxicity; it was known for the potential association with severe complications including myelosuppression, infections and secondary malignancies.21-23 The treating physician has to take all aspects into consideration when making individual treatment decisions together with their patients.

Treatment indication according to iwCLL guidelines24 is given when a progressive marrow failure develops or in the presence of symptomatic/active disease.

Asymptomatic patients with a low Binet (A or B) or Rai (0-II) stage should follow a watch and wait approach as treatment in this patient population has not resulted in a survival benefit yet.24

The CLL12 trial of the German CLL study group has lately evaluated early treatment with ibrutinib versus placebo in patients with Binet stage A and an increased risk of progression. While median event-free survival was improved in the ibrutinib group (not reached vs. 47.8 months in the placebo group), results of the primary endpoint overall survival are awaited.25 The SWOG S1925 trial (NCT04269902) currently investigates venetoclax and obinutuzumab as early intervention versus delayed therapy in newly diagnosed high-risk patients, results are not yet available.26 Therefore, the current standard for early-stage patients remains a watch and wait approach even with an unfavorable genetic risk profile.

2 FIRSTLINE TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITHOUT del17p/mutTP53

2.1 Fit patients with mutated IGHV status

Fit patients can be characterized by parameters such as good performance status, few comorbidities and a good creatinine clearance. These patients have a favorable risk profile when they exhibit a mutated IGHV status and no del17p/mutTP53.

One of the first and therefore most maturely studied and commonly used targeted agent for fit patients with mutated IGHV status is indefinite treatment with continuous BTK inhibitors. The first-generation BTK inhibitor ibrutinib was initially compared to chlorambucil monotherapy as firstline treatment in the RESONATE-2 trial confirming an improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) after 8 years of follow-up (PFS at 7 years: Ibrutinib 59% vs. chlorambucil 9%; median OS not reached for ibrutinib).27, 28 However, chlorambucil no longer is considered standard in patients with CLL. For older and unfit patients, chlorambucil was combined with a CD20 antibody for a better efficacy as shown in the CLL11 trial23 and since then served as control for many phase 3 trials evaluating targeted substances.29-32

The E1912 trial was thus set up to compare fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) as previous standard to ibrutinib-rituximab in younger patients under 65 years.33 In the latest long-term update of this trial after 5.8 years of follow-up, the difference in PFS was significant even in the IGHV mutated subgroup (5-year PFS rate ibrutinib-rituximab 83% vs. FCR 68%), but no OS benefit was achieved in this subgroup.34 These data support that targeted agents should be considered even in firstline treatment independently of genetic risk profile.

The UK FLAIR trial has compared the same regimen in an older patient population up to 75 years, but first data at 52.7 months do not show a difference in OS yet between ibrutinib-rituximab and FCR, although PFS was improved for ibrutinib-rituximab (median PFS ibrutinib-rituximab not reaches vs. FCR 67 months).35

The ALLIANCE A041202 trial has compared bendamustine and rituximab (BR) to ibrutinib-rituximab and ibrutinib alone in elderly patients at the age of 65 or older. Both ibrutinib-based treatments were superior concerning PFS (PFS at 2 years in all patients: ibrutinib-rituximab 88%, ibrutinib 87%, BR 74%) even in the IGHV mutated subgroup (median PFS for ibrutinib-rituximab: not reached, ibrutinib: not reached, BR: 51 months), although later than in the IGHV unmutated subgroup (median PFS for ibrutinib-rituximab: not reached, ibrutinib: not reached, BR: 39 months). However, no difference in OS could be shown between targeted therapy and chemoimmunotherapy. No significant difference in PFS between ibrutinib as monotherapy and ibrutinib-rituximab has been seen, so addition of this anti-CD20 antibody did not improve responses.36

The ILLUMINATE trial has evaluated ibrutinib-obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil-obinutuzumab in unfit patients and has also achieved a prolonged PFS (median not reached vs. 49 months), but no difference in OS could be shown.37 Comparing the 48-month PFS estimates between the ILLUMINATE and the RESONATE-2 trial, these were similar with 74% for ibrutinib alone and 76% for ibrutinib-obinutuzumab. Hence, the addition of this anti-CD20 antibody to ibrutinib does not seem to improve outcome either, although the second trial excluded patients with del17p.37-39 In light of these data, the addition of an anti-CD20 antibody to ibrutinib does not lead to additional efficacy and therefore would not be recommended.

Another option is the newer, more selective, second-generation BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib. In the ELEVATE TN trial, acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab was compared to chlorambucil-obinutuzumab in treatment naive CLL patients aged ≥65 years, or 18–65 years with comorbidities. After a prolonged follow-up of 4 years, median PFS was not reached for both acalabrutinib-containing arms and 27.8 months for obinutuzumab-chlorambucil in all patients. In the subgroup of IGHV mutated patients, median PFS was not reached for all treatment arms. The 48-month PFS rates were 89% for acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab compared to 81% for acalabrutinib monotherapy and 62% obinutuzumab-chlorambucil. In a post hoc analysis, prolonged PFS also was observed when comparing acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib as monotherapy. Although the trial was not powered for this comparison, the addition of obinutuzumab seems to improve responses and should be considered when initiating treatment with acalabrutinib.40

The ELEVATE RR trial has compared ibrutinib to acalabrutinib in relapsed/refractory CLL patients and has demonstrated a similar efficacy of both treatments with a median PFS of 38.4 months in both arms while the median OS was not reached. With regard to side effects, acalabrutinib should particularly be considered for patients with cardiac conditions, as all-grade atrial or flutter incidence was significantly lower for acalabrutinib (9.4% vs. 16.0% for ibrutinib). In general, acalabrutinib seems to be better tolerable as treatment discontinuations because of adverse events occurred in 14.7% of acalabrutinib-treated patients and 21.3% of ibrutinib-treated patients.41

Another second-generation BTK inhibitor that has fewer off-target effects than ibrutinib is zanubrutinib, with the approval of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicine Association (EMA) to be awaited. Within the SEQUOIA trial, the estimated 24-month PFS was prolonged for zanubrutinib versus BR as firstline treatment with 85.5% versus 69.5%, while 24-month OS was similar with 94.3% and 94.6%. Treatment benefit was particularly seen in patients with unmutated IGHV status, but not with mutated IGHV.42 All of these BTK inhibitors are a continuous therapy that has to be taken until intolerable toxicity or progression, which might lead to cumulative late side effects. Hence, a high number of discontinuations of 41%–49% is documented for ibrutinib after 17 months of treatment in the real world setting and can mainly be attributed to toxicity.43, 44 In light of good efficacy in all available BTK inhibitors the leading question in the near future might be rather how to individualize the different toxicity profiles to our patients needs than to define the BTK inhibitor with the best efficacy.

Alternatively, they could be offered a fixed-duration therapy with venetoclax-obinutuzumab for 12 months. This regimen has been evaluated by the CLL14 trial in treatment naïve patients with coexisting conditions defined as cumulative illness rating scale greater than six, a creatinine clearance of 30–69 ml/min, or both, including patients with high risk genetic profile.32 After a prolonged follow-up of 39.6 months, patients treated with venetoclax-obinutuzumab had a significantly longer median progression-free survival than patients treated with chlorambucil-obinutuzumab (median PFS for venetoclax-obinutuzumab: not reached; for chlorambucil-obinutuzumab: 35.6 months). In the IGHV mutated subgroup, median PFS was prolonged for venetoclax-obinutuzumab (not reached vs. 54.5 months for chlorambucil-obinutuzumab), but no OS benefit has been shown yet.45

Although evaluated in an unfit patient population, the combination has been approved also for firstline treatment of fit patients. First data of the CLL13 trial have shown encouraging results in fit CLL patients when comparing venetoclax-obinutuzumab to FCR or BR in the firstline setting. The first co-primary endpoint analysis showed superior undetectable MRD (uMRD) rates in the peripheral blood at month 15 when compared to chemoimmunotherapy (86.5% vs. 52.0%).46 Latest data presented at EHA 2022 suggest that high rates of uMRD translate into longer PFS which is defined as second co-primary endpoint. At a follow-up of 38.8 months, 3 year PFS rates were superior for venetoclax-obinutuzumab with 87.7% in comparison to FCR or BR with 75.5% in all patients, however, the difference was smaller in IGHV mutated patients with 93.6% for venetoclax-obinutuzumab and 89.9% for FCR or BR.47 While OS results are still awaited, chemoimmunotherapy might still be discussed on an individual basis for low-risk patients in light of long term data.21, 48, 49 However, the introduction of targeted drugs has provided substantial evidence supporting the notion of favoring these options over the use of chemoimmunotherapy even in low-risk patients.34, 47

2.2 Fit patients with unmutated IGHV status

Patients with unmutated IGHV face an adverse prognosis with shorter survival rates.50-53 After 5 years of follow-up within the RESONATE-2 trial, patients with unmutated IGHV treated with ibrutinib had a PFS of 67% versus 6% for chlorambucil38 and even after 8 years of follow-up, PFS was similar between patients with mutated and unmutated IGHV in the ibrutinib arm.28

When compared to chemoimmunotherapy within the E1912 trial, 5-year PFS rates in IGHV unmutated patients treated with ibrutinib-rituximab were at 75% as compared to FCR with 33% and OS difference at 5 years was significant (ibrutinib-rituximab: 95% vs. FCR: 84%).34 The difference in PFS was also seen in the older patient population of the FLAIR trial.35 Likewise in the elderly patient population of the Alliance A041202 trial, median PFS for ibrutinib and ibrutinib-rituximab was not reached versus 39 months for BR in patients with unmutated IGHV after a median follow-up of 33.6 months.36

After 4 years of follow-up within the ELEVATE TN trial, median PFS was not reached for the acalabrutinib-containing arms versus 22.2 months for obinutuzumab-chlorambucil in patients with unmutated IGHV. The 48-month PFS rates were 86% for acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab, 77% for acalabrutinib alone and only 4% for chlorambucil-obinutuzumab.40

Treatment benefit has also been shown for zanubrutinib in patients with unmutated IGHV.42

In the CLL14 trial, although median PFS in patients with unmutated IGHV mutational status was prolonged by the fixed-duration treatment regimen of venetoclax-obinutuzumab with 57.3 versus 26.9 months for chlorambucil and obinutuzumab after 39.6 months of follow-up, outcome is inferior compared to patients with mutated IGHV. In terms of OS, no difference could be seen in the IGHV unmutated subgroup.54

In light of the prolonged PFS in comparison to chemoimmunotherapy, targeted agents should be preferred for patients with unmutated IGHV.

2.3 Unfit patients

Unfit patients should be treated with less aggressive therapy regimens due to their coexisting conditions. Possible options for these patients include BTK inhibitors, in particular newer agents such as acalabrutinib due to their better toxicity profile or venetoclax-obinutuzumab. Venetoclax-obinutuzumab as fixed-duration regimen has shown prolonged PFS but not OS in comorbid patients when compared to chlorambucil-obinutuzumab.45 Likewise, ibrutinib-obinutuzumab as well as acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab have led to an improved PFS in comparison to chlorambucil and obinutuzumab, but not to a prolonged OS.37, 40

Hence, other factors like comorbidity burden and possible side effects as well as the option of a continuous versus fixed-duration therapy should also be taken into consideration and might limit choices for the individual patient. Treatment with targeted agents appeared feasible and effective also in frail patients aged 80 and older with comorbidities in a pooled analysis from different clinical trial. These frail patients historically have been often considered a group of patients, for which symptom control and feasibility should be the main intent. In focus patients even achieved a comparable survival to an age- and sex-matched population when treated with targeted agents.55

3 FIRSTLINE TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITH del17p/mutTP53

Patients who exhibit a del17p/mutTP53 have an aggressive course of disease and usually respond poorly to chemoimmunotherapy.56, 57 Although the ultimate treatment has not been identified, targeted inhibitors have shown better efficacy and should be recommended independently of physical fitness.58-60

Continuous therapy with ibrutinib has shown promising results in the firstline setting. Within a phase 2 trial evaluating only patients with del17p or mutTP53, the median PFS and OS were not reached and the estimated 6-year PFS was 60% and the estimated OS was 79%.61 In another phase 2 trial, the median time to progression was 53 months for patients with TP53 alterations treated with ibrutinib.62 When comparing ibrutinib and ibrutinib-rituximab to BR, median PFS was not estimable while it was 7 months for BR after a median follow-up of 38 months.36 Patients with del17p or mutTP53 achieved an estimated 48-month PFS rate of 74% while patients without del17p or mutTP53 were at 77% within the final analysis of the ILLUMINATE trial.37

Within the CLL14 trial, patients with del17p/mutTP53 had a significantly longer median PFS of 49.0 months when treated with venetoclax-obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil-obinutuzumab with 20.8 months.54 If retreatment with venetoclax-obinutuzumab would be an option for patients with progressive disease is currently being investigated within the ReVenG trial (NCT04895436).63

The PI3K inhibitor idelalisib in combination with rituximab has also shown activity in high-risk CLL,64 but it should be used with caution and only considered in high risk CLL if there are contraindications against BTK inhibitors and venetoclax. It could only be discussed as last option because of its very severe side effects like fatal and/or serious infections, hepatotoxicity, diarrhea or colitis, pneumonitis, and intestinal perforation.65

In a recent retrospective study on 130 patients with TP53 dysfunction who had received BTKi with or without venetoclax and with or without CD20 antibody in the firstline setting, the authors reported good 4-year outcomes, with very good outcomes for patients treated with doublets or triplets.66

In addition, the authors also suggest that low-burden TP53 alterations should not be ignored, a finding that is in line with the recently published study.67

The CLL16 trial is currently recruiting patients with high risk CLL exhibiting a complex karyotype or a del17p/mut TP5368 and was set up to compare venetoclax-obinutuzumab to the triple combination with venetoclax-obinutuzumab plus acalabutinib over 14 months and 10 more cycles of acalabrutinib in case of detectable MRD (NCT05197192).

However, patients with high-risk disease will progress eventually even with targeted treatment and there is still no cure for CLL except for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. After which therapy line this therapy should be offered needs to be discussed on an individual basis, as it comes along with high rates of mortality and morbidity.69-71

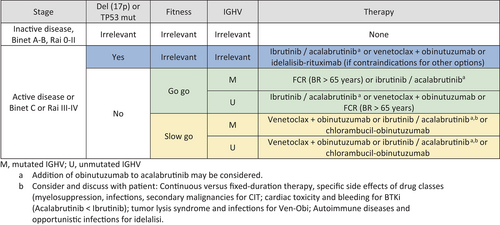

4 PROPOSED TREATMENT ALGORITHM

An adapted version of the treatment algorithm as proposed by Hallek and Al-Sawaf7 is depicted in Figure 1 and should be adjusted in case of relevant comorbidities or contraindications. In general, patients are stratified according to fitness as well as TP53 and IGHV status. Patients with mutated IGHV and no del17p or mutTP53 are preferably treated with venetoclax-obinutuzumab. Most patients prefer treatment with targeted agents due to the more favorable side effect profile, although chemoimmunotherapy might still be an option in low risk disease. Fit patients with unmutated IGHV can be offered a BTK inhibitor like ibrutinib or acalabrutinib in first place as the E1912 trial has shown an improved OS.34 Treatment with venetoclax-obinutuzumab or a BTK inhibitor can be offered unfit patients with mutated or unmutated IGHV, with respect to comorbidities. In frail and very old patients, with a high risk of polypharmacy and where the balance between efficacy and toxicity is highly relevant and inpatient treatment should be avoided, acalabrutinib could be a feasible option. For high risk patients with del17p or mutTP53, treatment with BTK inhibitors is favored. When deciding which of these both agents is preferred, in addition to patients, preference several factors should be taken into account like cardiac comorbidities, concomitant medication like anticoagulants and proton pump inhibitors and frequency of dosing. If a rapid reduction in tumor burden is needed, the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib can be considered.

However, as the direct comparison of continuous therapy with BTK inhibitors to fixed duration venetoclax-based regimen is pending, no clear recommendation can be given which treatment should be preferred. This question is currently being addressed within the CLL17 trial of the German CLL study group (NCT04608318) comparing ibrutinib to venetoclax-obinutuzumab and venetoclax-ibrutinib, but the study is still open for recruitment.

5 OUTLOOK

Oral inhibitors have broadened therapeutic possibilities for CLL patients and choices can be made on a more individual basis. Besides a continuous treatment with the different BTK inhibitors, also fixed-duration therapies are being introduced that might also limit toxicities. Venetoclax-obinutuzumab is the first fixed-duration targeted therapy approved for firstline treatment of CLL.32 As the risk for resistance-associated mutations increases with longer duration of treatment and acquired secondary resistance accounts for the majority of progressions under continuing treatment, further fixed duration combinations are being investigated in clinical trials.72

Another promising combination to combine both agents while still time-limited is venetoclax-ibrutinib that consists only of oral medication. It was evaluated as firstline treatment in high-risk and older patients with CLL who received ibrutinib alone for 3 months followed by the combination with venetoclax over 24 months. An estimated 1-year PFS of 98% and OS of 99% were achieved.73

Within the CAPTIVATE trial, an MRD cohort and a separate fixed-duration cohort have been enrolled. In the fixed duration cohort, patients aged ≥18 and ≤70 years received three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib followed by 12 months of combination therapy with venetoclax. This cohort achieved a CR rate of overall 55% and 24-month OS was at 98%. The estimated 24-month PFS rate of 95% in all patients and even 84% in patients with del17p/mutTP53.74 Within the MRD-guided treatment group, the 1-year disease free survival rate was 95% in patients achieving uMRD randomly assigned to placebo after 12 cycles of combination therapy and 100% for ibrutinib while the estimated 30-month PFS rates were 95% for patients receiving placebo and 100% for ibrutinib.75

The GLOW trial has also shown higher rates of undetectable MRD after treatment with ibrutinib-venetoclax in comparison with chlorambucil-obinutuzumab (bone marrow: 51.9% vs. 17.1%; peripheral blood: 54.7% vs. 39.0%). The PFS rate during the first 12 months after end of treatment in the ibrutinib-venetoclax arm was above 90% for both, patients with uMRD and with detectable MRD.29 Caution arose from the safety data reporting four deaths during ibrutinib lead-in reminding the choice of the specific BTK inhibitor should take coexisting conditions into account in particular in this elderly patient populations.29

Time-limited therapies in firstline CLL are currently approved only as fixed-duration treatments and MRD guided therapies are not recommended in every day practice.6

Multiple studies are currently testing an MRD guided approach for individual treatment duration.76, 77 If MRD-guided approaches will be superior to the fixed-duration option will have to be evaluated within a phase 3 trial.

Triple combinations have also shown promising results in phase 2 trials. A trial conducted by Rogers investigated the triple combination of obinutuzumab-ibrutinib-venetoclax for 14 cycles and has shown an estimated 36-month PFS of 95%.78 The combination of obinutuzumab-acalabrutinib-venetoclax given until Day 1 of cycle 16 with the option to stop treatment with uMRD or until Day 1 of cycle 25 yielded a rate of complete remissions with uMRD in the bone marrow of 38%.79

In a trial comparing obinutuzumab-zanubrutinib-venetoclax in a MRD-guided approach, uMRD in both blood and bone marrow was achieved in 89% of the patients after a median treatment duration of 10 months and a median follow-up of 25.8 months.80

If triple combinations of targeted agents might improve outcomes substantially or if toxicities and early development of resistances will limit this approach is currently being investigated in phase 3 trials. The EA9161 trial compares ibrutinib-obinutuzumab with ibrutinib as continuous therapy to fixed duration ibrutinib-venetoclax-obinutuzumab in treatment naïve patients up to 70 years (NCT03701282) and results are awaited. A similar design with MRD-guided termination of ibrutinib after 14 months is still recruiting elderly patients at 70 years of age and older (NCT03737981). Within the phase 3 CLL13 trial, higher uMRD rates and the longest PFS have been observed with the triple combination of venetoclax-obrutinib-obinutuzumab, but also more toxicity like grade 3–4 infections.46, 47 Longer follow-up will provide more clarity if efficacy outweighs the risks.

With these options and new promising agents on the horizon, the future for CLL treatment looks bright. Next, the optimal sequencing of therapies and treatment options for double refractory patients or patients where targeted agents are not suitable because of drug interactions or comorbidities need to be studied further within the heterogenous population of patients with CLL. Additionally, clinical trial participation should be discussed with patients and global access to treatment with targeted agents should be a common goal to actively move forward to.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Nadine Kutsch received research funding and travel support from Gilead Sciences, Inc., Honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche, and travel support from AstraZeneca, Janssen and Celgene. Anna Maria Fink received research funding from Astra Zeneca and Celgene and travel grants from AbbVie. Kirsten Fischer received honoraria from AbbVie, Roche and Advisory Board: AstraZeneca.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.