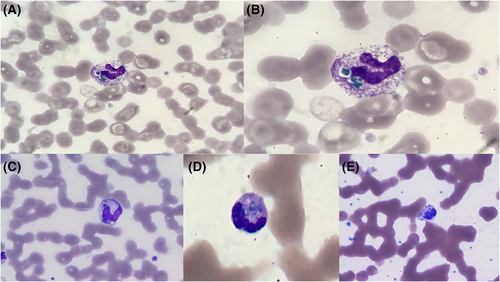

An unanticipated finding on peripheral smear: Blue-green crystals of impeding death?

A 71-year-old Caucasian gentleman presented to our hospital with dyspnea and tachypnea of a day's duration. These symptoms started earlier on the day of presentation after eating lunch. He is a resident of a nursing home. Four months prior to presentation, he was diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme of the left frontal lobe of the brain that was subsequently complicated by a stroke event. He was being treated with prolonged steroid and radiation therapy. In the emergency room, the patient was not febrile. He appeared lethargic but was able to answer simple questions. His pulse oximetry was 88% and supplemental oxygen was required. His respiratory rate ranged from 21 to 35 breaths per min, and arterial blood gas analysis on room air revealed a respiratory alkalosis with pH 7.52, pCO2 32 mm Hg, pO2 56.4 mm Hg and base excess 4.1 mmol/L. A computed tomography of the chest revealed multiple confluent airspace opacities in the left lower lobe and anterior segment of the right upper lobe with a cavitary lesion measuring 2.5 × 7.8 cm. The patient required admission to our intensive care unit and was treated with continuous positive airway pressure and empiric antibiotics for clinical suspicion for sepsis. He did not become hypotensive and did not require inotropes or pressor support. The white blood cell count was 5000 cells per mm3 with differential: 83% segmented neutrophils, 1% lymphocytes, 8% bands, and 3% monocytes. Few Döhle bodies and 2+ toxic granulations were appreciated in neutrophils but no cytoplasmic vacuoles. The alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was elevated to 107 IU/L, and the lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) was 314 IU/L. The lactic acid was 2.1 mmol/L. Blood cultures revealed Escherichia coli within 24 h of incubation. The acid-fast bacilli stain on sputa were negative thrice. Review of the peripheral smear showed sparse peculiar blue-green inclusions inside the granulocytes and monocytes (See 1A-E). As a result of worsening respiratory and mental status, the family requested comfort measures and the patient died on the third day of hospitalization.

Smith first described in 1967, the case of an infant who died at 7 mo of age because of biliary cirrhosis caused by congenital atresia of the bile ducts and noted to have dull green, circular or oval inclusions in the cytoplasm of granulocytes and monocytes.1 It was not until Harris et al., in 2009 and Jazaerly et al., in 2014, who proposed the finding of these inclusions are likely related to liver failure and could serve as a prognostic indicator of impending death.2, 3 Hodgson et al. proposed the term “critical green inclusions” to be used and communicated by laboratory technicians.4 In their 20 case-report series where inclusions were identified, they reported five patients who survived. In addition, Hodgson et al. hypothesized the green inclusions to represent lipofuscin-like substance that was taken up by phagocytosis following ischemic injury to the liver. They based this hypothesis on the finding of prominent centrilobular hepatocellular lipofuscin on postmortem livers.4 Although the composition of these green neutrophilic inclusions remains largely unknown, they have variably been associated with laboratory findings such as leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, elevations in γ-glutamyl transferase, LDH and troponin; and clinical conditions such as malignancy, coagulopathy, lactic acidosis, chronic renal disease, infection, and sepsis.5 Jazaerly's et al. case involved a patient who died because of septic shock caused by E. coli bacteremia with the ALT being 116 U/L. Hodgson's et al. case series also included patients with septic shock. We hypothesize that in our case the green inclusions were the result of sepsis and liver injury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. Timothy Pal for the peripheral smear images and Dr. Tesfa Asrat for her editorial assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.